Published online Jan 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.150

Revised: May 28, 2005

Accepted: June 2, 2005

Published online: January 7, 2006

A 39-year-old male patient complaining of bilateral hand joint arthralgia was evaluated and found to have chronic hepatitis C and systemic sarcoidosis involving lung, skin, liver, and spleen. Hepatic and cutaneous sarcoidoses were confirmed by the presence of numerous noncaseating granulomas on histological examination. Pulmonary and splenic involvements were diagnosed by imaging studies. Fifteen months later, the sarcoidotic lesions in lung, liver, and spleen were resolved by radiological studies and a liver biopsy showed no granuloma but moderate to severe inflammatory activity. systemic sarcoidosis is a rare comorbidity of chronic hepatitis C which may spontaneously resolve.

- Citation: Kim TH, Joo JE. Spontaneous resolution of systemic sarcoidosis in a patient with chronic hepatitis C without interferon therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(1): 150-153

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i1/150.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.150

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology, and is characterized by widespread noncaseating granulomas in many organs. Most commonly sarcoidosis affects the lungs, followed by mediastinal, hilar lymph nodes, and skin. Hepatic involvement of systemic sarcoidosis is frequently demonstrated[1]. In fact, sarcoidosis is the most common cause of hepatic granulomas in the West, and infectious disorders resulting from HCV or HIV infections are possible comorbidities of hepatic sarcoidosis. Most reported cases of HCV associated-sarcoidosis are not the consequence of HCV infection per se, but are the results of interferon antiviral therapy[2,3]. However, cases of HCV associated-sarcoidosis without interferon therapy have also been recently reported and the possibility of HCV infection per se inducing sarcoidosis by activating host immune systems has been suggested[3,4].

Active sarcoidosis and active viral hepatitis are somewhat incompatible because sarcoidosis is a reflection of activated host cellular immunity to an unknown stimulant, while an augmented cellular immunity is one of the main mechanisms by which HCV replication is suppressed by antiviral agents. Thus, changes in the activities of viral hepatitis vs sarcoidosis are worth observing when they simultaneously affect a patient.

We experienced a case of systemic sarcoidosis in a patient with chronic hepatitis C who did not receive interferon therapy, and observed the spontaneous resolution of sarcoidotic lesions with more aggravated hepatitis activities during the natural course of this rare comorbidity.

A 39-year-old male patient was admitted because of bilateral hand joint arthralgia, who developed suddenly and impaired hand grip. His serum rheumatoid factor titer (102.7 kU/L) was elevated but other associated clinical features were not compatible with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Moreover, his joint symptom improved in 2 d without specific medication.

The patient had suffered from diabetes and chronic hepatitis C for 20 years and received treatment with oral hypoglycemic agents and subcutaneous insulin injections. He was told that his hepatitis activities were mild and need not receive antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C. He was in a relatively good condition until 4 mo prior to admission, when he developed fatigue, myalgia, and a mild dry cough. He visited other hospitals for these symptoms and was found to have small pulmonary nodules, which were attributed to past tuberculous infection. His respiratory symptoms improved over the intervening 4 mo, but fatigue and weakness persisted.

A physical examination disclosed no remarkable findings except for three oval brownish papular skin rashes on the periumbilical and lower back areas. Chest X-ray revealed tiny nodules scattered throughout the lung fields and maxillary sinus haziness was found on skull X-ray. Complete blood cell counts with differential counts were all within the normal ranges. Serological markers for HBV infection (HBsAg and anti-HBs) were negative but anti HCV antibody was positive. A sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detected serum HCV RNA and identified the genotype of the HCV as 1b. Blood chemistry tests revealed 23 IU/L aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 29 IU/L alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 237 U/L alkaline phosphatase, 8.3 g/dL total protein, 3.8 g/dL albumin, 0.8 mg/dL total bilirubin, 9.4 mg/dL total calcium, 3.0 mg/dL phosphorus, 7.6% hemoglobin A1C, 201 mg/dL fasting blood sugar, 90% (11.6 s, INR 1.05) prothrombin time, 3.3 ng/mL alpha-fetoprotein, 17.3 mg/dL BUN, 0.9 mg/dL creatinine, 1.34 mg/dL free T4 (normal: 0.9-1.8 mg/dL), and 2.84 mIU/L TSH (normal: 0.3-6.5 mIU/L). Cryoglobulin was negative and serum angiotensin converting enzyme concentration was in the upper normal range, 51.8 U/L (normal: 8-52 U/L).

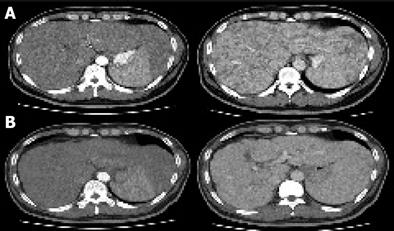

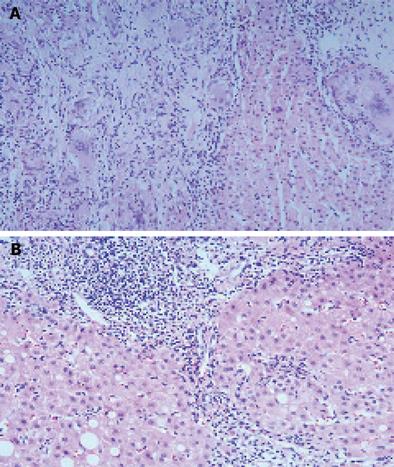

Abdominal ultrasonography showed multiple ill-defined low echoic nodular lesions in the liver and an enlarged spleen implying the presence of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, but no evidence of enhancement was identified among the numerous low-attenuation nodules scattered throughout the liver and spleen on his abdominal CT scan (Figure 1A). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic findings were normal and there was no clinical evidence of portal hypertension. A liver biopsy was performed as a basal evaluation of the chronic HCV infection and as a diagnostic procedure for the multiple hepatic nodules, which revealed numerous granulomas with multinucleated giant cells and occasional asteroid bodies in addition to the features of chronic hepatitis such as a mild inflammatory reaction and moderate fibrosis (Figure 2A). Special stains for tuberculosis and fungus, using acid fast bacillus (AFB) and periodic acid Schiff (PAS) were negative, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis nucleic acid was not detected by PCR in the liver tissue.

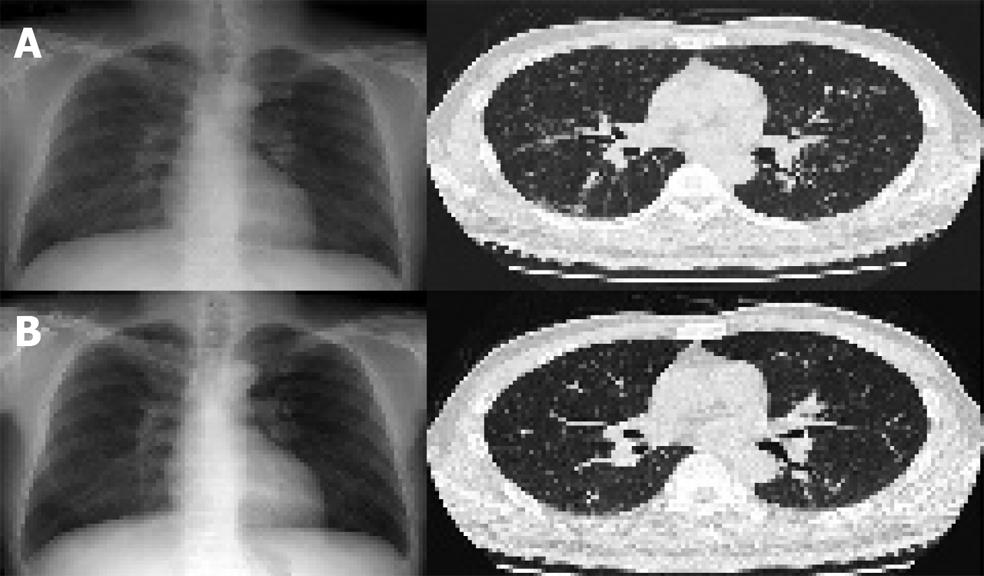

A high-resolution chest CT scan showed multiple fine nodules distributed in peribronchial areas, especially in the upper and middle lobes, without lymph node enlargement, which was compatible with type III pulmonary sarcoidosis (Figure 3A). Lung tissues obtained by transbronchial lung biopsy revealed a patchy distribution of mild interstitial and perivascular fibrosis, without distinctive granulomas or significant inflammatory cell infiltrations, and stains for AFB and PAS and PCR was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis nucleic acids. An analysis of cell types obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage showed that 42% were lymphocytes that consisted of CD4+ cells (63%) and CD8+ cells (37%), a CD4/CD8 ratio of 1.7. Cytologic analysis of bronchial washing fluid for malignant cells was negative and his pulmonary function test was normal.

Granulomatous inflammation with asteroid bodies and multinucleated giant cells were also found in skin biopsy specimens of the periumbilical lesions. Echocardiographic and ophthalmologic evaluations and a thyroid function test, performed to determine the presence of indolent organ involvement, were all within the normal ranges. With a diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis involving lung, liver, skin, spleen, and mild chronic hepatitis C, no specific therapies for either sarcoidosis or chronic hepatitis C were adopted, because there was no definitive evidence for significant organ dysfunction and disease progression.

Radiologic and biochemical examinations after 2 months showed no significant changes. After then, he went abroad and was not followed up for a year. Fifteen months later, the hepatosplenic and pulmonary sarcoidotic lesions were remarkably improved on radiologic examination (Figures 1B and 3B) and a liver biopsy showed no remnant granulomas, but moderate to severe inflammatory activities in the lobular and periportal areas, and grade 3 septal fibrosis (Figure 2B). Blood chemistry showed a markedly elevated serum transaminase level (AST 392 IU/mL, ALT 608 IU/mL) with a high serum viral load (serum HCV RNA 2.6×105 IU/mL).

Liver involvement in sarcoidosis is reported in 40%-70% of patients, but significant hepatic dysfunction is rare[5]. The histologic features of hepatic sarcoidosis are variable. Granulomas are identified in all the patients and cholestasis presenting as ductal or periductal inflammation and ductopenia are evident in more than 50% of patients. Necroinflammatory changes and vascular changes are found in 41% and 29%, respectively, and hepatic fibrosis is also found in about 20% of patients[6]. Asteroid bodies are found in about 10% of hepatic sarcoidosis cases[1]. The hepatic histologic findings in the present case are compatible with those of hepatic sarcoidosis, although chronic HCV infection may also have contributed. Hypodense nodular lesions in the liver and spleen as seen in the CT scans of this patient have been reported to be a characteristic feature of hepatosplenic sarcoidosis[7]. Splenic sarcoidosis appears as a nonspecific splenomegaly with retroperitoneal lymphadenopathies in most cases of abdominal sarcoidosis, and approximately 15% of cases present as multiple focal low-attenuating nodules[8,9]. The constitutional symptoms, arthritis, paranasal sinusitis, pulmonary nodules, and noncaseating granulomas in the liver and skin tissues of this patient, are all consistent with the characteristic features of systemic sarcoidosis.

Reported comorbidities of sarcoidosis include infectious diseases, neoplastic disorders, and immunologic-inflammatory diseases such as lupus erythematosus, myasthenia, and primary biliary cirrhosis. HCV infection is reported to be the most commonly associated infectious disease of sarcoidosis, however most cases are associated with interferon antiviral therapy[2,3]. Treatment-associated cases of sarcoidosis have been reported in many disorders such as chronic hepatitis C, chronic myelogenous leukemia, renal cell carcinoma and lymphoma, in which the beneficial effect of interferon therapy has been established. Importantly, in cases of chronic hepatitis C, interferon can both induce sarcoidosis[10] and reactivate sarcoidosis[11], and interferon-based combination antiviral regimens cannot eliminate the occurrence of sarcoidosis[12].

Interferon not only has direct antiviral activity but also has potent immune stimulating activities especially on T helper (Th1) immune response[10,13], which is also involved in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis[14,15]. Granulomas in sarcoidosis have an abundance of CD4+ T lymphocytes and mononuclear phagocytes, which are thought to be a result of cytokine stimulation and immunologic dysregulation[16]. Moreover, ribavirin, an antiviral agent which augments the anti-HCV effect of interferon in chronic hepatitis C, also enhances Th1 cytokine response, while inhibiting Th2 cytokine response[17,18]. Thus it appears that treatment-associated sarcoidosis in chronic hepatitis C is mediated by an augmentation of Th1 immune response.

Cases of sarcoidosis and chronic hepatitis C with no history of interferon therapy are rarely reported. Bonnet et al [4] reported two cases of pulmonary sarcoidosis associated with untreated chronic hepatitis C, one presented with respiratory and cutaneous symptoms that responded to corticosteroid therapy, the other manifested as cervical lymph adenopathies with pulmonary symptoms and responded poorly to corticosteroids. However, sarcoidosis hepatic involvement was absent in both cases, liver biopsies showed features of chronic hepatitis but no granulomas. Our case is unique in that treatment-unrelated hepatic sarcoidosis and its spontaneous resolution were proven histologically in this chronic hepatitis C patient.

Interferon-based antiviral therapy is the standard treatment for chronic hepatitis C, but careful evaluations are required before starting the treatment because many adverse events can be induced by interferon. Flu like symptoms, cytopenia, depression, hyperglycemia, and thyroid dysfunctions are commonly encountered during interferon therapy. Interstitial lung disease, cardiomyopathy, and retinopathy rarely develop. Thus severe depression, autoimmune disorders, and uncontrolled diabetes contraindicate interferon therapy[19]. In addition to these disorders, sarcoidosis must also be considered, not only during interferon therapy but also before antiviral therapy, since sarcoidosis may preclude interferon administration.

The clinical course of pulmonary sarcoidosis is variable with a spontaneous remission rate of 40% over a 6-mo observation period before steroid therapy[20]. In addition, the clinical course of treatment-associated sarcoidosis in chronic viral hepatitis is also variable. The discontinuation of interferon with or without corticosteroid therapy usually improves sarcoidotic lesions[11], but the remission of pulmonary sarcoidosis has also been reported though interferon therapy is continued[21]. However, the natural course of treatment-unrelated sarcoidosis in chronic hepatitis C has not been previously reported.

Although corticosteroid therapy can suppress the active inflammatory reaction of sarcoidosis, its effect on clinical outcome has not been fully established. Moreover, it often provokes serious adverse events, such as hepatic functional deterioration and enhanced viral replication[22]. In a few cases of hepatic sarcoidosis, corticosteroid therapy could normalize liver enzymes but could not achieve histologic improvements[23-25]. Due to the potential provocation of viral replication and uncertain efficacy in a clinically stable condition, the patient was simply observed without corticosteroid therapy

In view of the fact that sarcoidosis is a manifestation of an augmented (Th1) immune response to an unidentified stimulant and that interferon-induced immune activation is an important mechanism of viral replication suppression in chronic hepatitis C, hepatitis activities may be suppressed when chronic hepatitis C is combined with active sarcoidosis. In fact, the present case provides clinical evidence that supports this postulation, because serum ALT levels and histologic hepatitis activities were mild when the patient initially presented with active systemic sarcoidosis; whereas 15 mo later when the sarcoidotic lesions resolved, hepatitis activities were aggravated with a higher serum ALT level and a high serum HCV RNA titer.

In conclusion, it is prudent to keep in mind that systemic sarcoidosis is a rare comorbidity of chronic hepatitis C which may spontaneously resolve.

S- Editor Wang XL L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Wang J

| 1. | Bilir M, Mert A, Ozaras R, Yanardag H, Karayel T, Senturk H, Tahan V, Ozbay G, Sonsuz A. Hepatic sarcoidosis: clinicopathologic features in thirty-seven patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:337-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bonnet F, Dubuc J, Morlat P, Delbrel X, Doutre MS, de Witte S, Bernard N, Lacoste D, Longy-Boursier M, Beylot J. [Sarcoidosis and comorbidity: retrospective study of 32 cases]. Rev Med Interne. 2001;22:619-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ramos-Casals M, Mañá J, Nardi N, Brito-Zerón P, Xaubet A, Sánchez-Tapias JM, Cervera R, Font J. Sarcoidosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: analysis of 68 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2005;84:69-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bonnet F, Morlat P, Dubuc J, De Witte S, Bonarek M, Bernard N, Lacoste D, Beylot J. Sarcoidosis-associated hepatitis C virus infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:794-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1224-1234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1038] [Cited by in RCA: 960] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Devaney K, Goodman ZD, Epstein MS, Zimmerman HJ, Ishak KG. Hepatic sarcoidosis. Clinicopathologic features in 100 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:1272-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thanos L, Zormpala A, Brountzos E, Nikita A, Kelekis D. Nodular hepatic and splenic sarcoidosis in a patient with normal chest radiograph. Eur J Radiol. 2002;41:10-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Robertson F, Leander P, Ekberg O. Radiology of the spleen. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:80-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Scott GC, Berman JM, Higgins JL. CT patterns of nodular hepatic and splenic sarcoidosis: a review of the literature. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1997;21:369-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hoffmann RM, Jung MC, Motz R, Gössl C, Emslander HP, Zachoval R, Pape GR. Sarcoidosis associated with interferon-alpha therapy for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1998;28:1058-1063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li SD, Yong S, Srinivas D, Van Thiel DH. Reactivation of sarcoidosis during interferon therapy. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:50-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pérez-Alvarez R, Pérez-López R, Lombraña JL, Rodríguez M, Rodrigo L. Sarcoidosis in two patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with interferon, ribavirin and amantadine. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:75-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Brinkmann V, Geiger T, Alkan S, Heusser CH. Interferon alpha increases the frequency of interferon gamma-producing human CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1655-1663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | James DG. Sarcoidosis 2001. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:177-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hunninghake GW, Crystal RG. Pulmonary sarcoidosis: a disorder mediated by excess helper T-lymphocyte activity at sites of disease activity. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:429-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 546] [Cited by in RCA: 506] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fireman EM, Topilsky MR. Sarcoidosis: an organized pattern of reaction from immunology to therapy. Immunol Today. 1994;15:199-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tam RC, Pai B, Bard J, Lim C, Averett DR, Phan UT, Milovanovic T. Ribavirin polarizes human T cell responses towards a Type 1 cytokine profile. J Hepatol. 1999;30:376-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hultgren C, Milich DR, Weiland O, Sällberg M. The antiviral compound ribavirin modulates the T helper (Th) 1/Th2 subset balance in hepatitis B and C virus-specific immune responses. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2381-2391. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Sievert W. Management issues in chronic viral hepatitis: hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:415-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gibson GJ, Prescott RJ, Muers MF, Middleton WG, Mitchell DN, Connolly CK, Harrison BD. British Thoracic Society Sarcoidosis study: effects of long term corticosteroid treatment. Thorax. 1996;51:238-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Luers C, Sudhop T, Spengler U, Berthold HK. Improvement of sarcoidosis under therapy with interferon-alpha 2b for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 1999;30:347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gruber A, Lundberg LG, Björkholm M. Reactivation of chronic hepatitis C after withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy. J Intern Med. 1993;234:223-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nores JM, Chesneau MC, Charlier JP, de Saint-Louvent P, Nenna AD. [A case of hepatic sarcoidosis. Review of the literature]. Ann Gastroenterol Hepatol (Paris). 1987;23:257-260. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Brailski Kh, Dimitrov B, Damianov B, Dinkov L, Todorov D. [Case of sarcoidosis with predominant involvement of the liver and lymph nodes]. Vutr Boles. 1986;25:83-91. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Mueller S, Boehme MW, Hofmann WJ, Stremmel W. Extrapulmonary sarcoidosis primarily diagnosed in the liver. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1003-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |