Published online Feb 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i8.1109

Revised: August 2, 2004

Accepted: September 9, 2004

Published online: February 28, 2005

AIM: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) re-activation often occurs spontaneously or after withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Severe exacerbation, sometimes developing into fulminant hepatic failure, is at high risk of mortality. The efficacy of corticosteroid therapy in “clinically severe” exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B has not been well demonstrated. In this study we evaluated the efficacy of early introduction of high-dose corticosteroid therapy in patients with life-threatening severe exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B.

METHODS: Twenty-two patients, 14 men and 8 women, were defined as “severe” exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B using uniform criteria and enrolled in this study. Eleven patients were treated with corticosteroids at 60 mg or more daily with or without anti-viral drugs within 10 d after the diagnosis of severe disease (“early high-dose” group) and 11 patients were either treated more than 10 d or untreated with corticosteroids (“non-early high-dose” group).

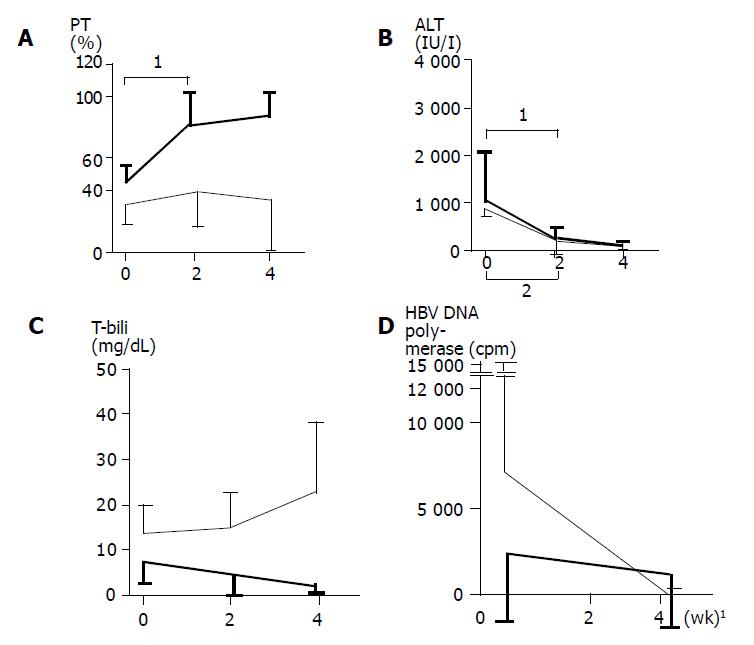

RESULTS: Mean age, male-to-female ratio, mean prothrombin time (PT) activity, alanine transaminase (ALT) level, total bilirubin level, positivity of HBeAg, mean IgM-HBc titer, and mean HBV DNA polymerase activity did not differ between the two groups. Ten of 11 patients of the “early high-dose” group survived, while only 2 of 11 patients of the “non-early high-dose” group survived (P<0.001). During the first 2 wk after the introduction of corticosteroids, improvements in PT activities and total bilirubin levels were observed in the “early high-dose” group. Both ALT levels and HBV DNA polymerase levels fell in both groups.

CONCLUSION: The introduction of high-dose corticosteroid can reverse deterioration in patients with “clinically life-threatening” severe exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B, when used in the early stage of illness.

- Citation: Fujiwara K, Yokosuka O, Kojima H, Kanda T, Saisho H, Hirasawa H, Suzuki H. Importance of adequate immunosuppressive therapy for the recovery of patients with “life-threatening” severe exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(8): 1109-1114

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i8/1109.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i8.1109

It is well recognized that exacerbation of hepatitis B may occur in chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) carriers spontaneously or in relation to cytotoxic or immunosuppressive therapy. A clinical picture of acute hepatitis, and even severe exacerbation, sometimes fulminant hepatic failure, may develop and is associated with high mortality[1]. In a retrospective survey in Japan, a 53% incidence of severe hepatitis with a 24% mortality rate (mortality rate of 45% in severe hepatitis) is reported in relation to chemotherapy in HBV carriers with hematologic malignancies[2]. For the treatment of patients with severe exacerbation without malignancies who progressed to serious deterioration, liver transplantation may be considered. However, the problems of the shortage of donor- livers and the high cost of liver transplantation still remain in Japan. Thus, therapies other than transplantation must be further investigated for the hepatitis B patients with severe exacerbation.

In HBV infection, liver injury is considered to be induced mainly by CTL-mediated cytolytic pathways of infected hepatocytes[3]. Examination of B and T lymphocyte functions in patients with chronic hepatitis B revealed that serum alanine transaminase (ALT) level is closely correlated with suppressor T lymphocyte activity[4]. Sjogren et al[5] suggested that corticosteroids modulate the activity of chronic hepatitis B by suppressing the host-immune response to HBV antigens. Nouri-Aria et al[6] have shown the defects in suppressor T lymphocyte activity in chronic hepatitis B. Therefore, it must be reasonable to treat chronic hepatitis B patients with corticosteroids in order to inhibit excessive immune response and prevent cytolysis of infected hepatocytes.

Corticosteroids have been used in the treatment of chronic active hepatitis B since the 1970s. However, in recent years corticosteroids have not been used for the routine management of chronic hepatitis B since the advantage of their use was not confirmed by control studies. For example, Lam et al[7] reported that long-term low-dose prednisolone treatment delays remission and increases relapse, complications, and death in a pair-randomized study, indicating that prednisolone has a deleterious effect on chronic active hepatitis B. Hoofnagle et al[8] showed that 4 wk of pre-dnisolone treatment produces no benefit in patients with chronic hepatitis B and is even harmful because of worsening of histopathological features. Scullard et al[9] showed that immunosuppressive therapy has a potentiating effect on hepatitis B viral replication in patients with chronic active hepatitis. However, these studies mainly dealt with cases of clinically “non-severe” hepatitis that is not urgently life-threatening and the effects of corticosteroid treatment for “potentially life-threatening” severe exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B as well as the timing and dose of treatment have not been well demonstrated. Lau et al[10] reported that the re-introduction of long-term high-dose corticosteroids in the early phase of reactivation after the withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy prevents both progressive clinical deterioration and the potential need for orthotopic liver transplantation.

In this study, we investigated the clinicopathological features of chronic hepatitis B patients with severe exacerbation selected by uniform criteria, and treated with early introduction or reintroduction of sufficient doses of corticosteroids, in order to clarify the benefits and limitations of the effects of corticosteroids for amelioration of clinically severe exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B.

Twenty-two chronic hepatitis B patients with severe exacerbation, who were admitted to our liver unit (Chiba University Hospital and related hospitals) during the last decade, were studied. The diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B viral carriers was made, based on either the positivity of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for at least 6 mo before entry, or the positivity of hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb) at high titer and negativity or low titer of IgM anti-hepatitis B core antibody (IgM-HBc) in patients with follow-up periods less than 6 mo before entry. The patients, fulfilling the following three criteria during the course, were defined as having severe exacerbation: prothrombin time (PT) activity less than 60% of normal control, total bilirubin (T-bili) greater than 3.0 mg/dL, and ALT greater than 300 IU/L. All patients had a poor general condition, manifested as general malaise, fatigue, jaundice, edema, ascites and encephalopathy. Histological examination was performed in the convalescent phase or after death in 16 patients.

All patients were negative for IgM anti-HAV antibody, anti-hepatitis D antibody, anti-HCV antibody, HCV RNA, IgM anti-Epstein-Barr virus antibody (IgM-EBV), IgM anti-herpes simplex virus antibody (IgM-HSV), IgM anti-cytomegalovirus antibody (IgM-CMV), anti-nuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, liver kidney microsomal antibody-1 and anti-mitochondrial antibody. Patients with a history of recent exposure to drugs and chemical agents and histories of recent heavy alcohol in-take were ruled out. None of the patients had clinical and laboratory evidence of acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

Eleven patients were treated with “early high-dose” of corticosteroids (Table 1). Informed consent was obtained from patients or their appropriate family members. Corticosteroids, 60 mg or more prednisolone daily, was administered within 10 d after the diagnosis of severe disease using the above-mentioned criteria. The dosage of prednisolone was maintained at least for 4 d. When the patients showed a trend toward remission in PT[11], the dosage was reduced by 10 mg at least every 4 d to 30 mg. Then, the dosage was reduced by 2.5 or 5 mg every 2 wk or longer, depending on the decreasing trend of the ALT level.

| Pt | Age (yr) | Sex | Therapy drug | Duration (d)1 | Condition | History of immunosuppresive or cytotoxic therapy | Outcome |

| Patients who received early introduction of high-dose corticosteroids | |||||||

| 1. | 27 | M | MPSL/PSL | 1 | Ulcerative colitis | + | Death |

| 2. | 36 | M | PSL | 2 | - | Re covery | |

| 3. | 41 | F | PSL | 3 | - | Recovery | |

| 4. | 27 | M | PSL | 4 | - | Recovery | |

| 5. | 41 | F | PSL | 4 | Schizophrenia | - | Recovery |

| 6. | 33 | M | PSL+Lam | 4 | - | Recovery | |

| 7. | 68 | F | PSL+Lam | 4 | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | + | Recovery |

| 8. | 56 | M | PSL | 5 | - | Recovery | |

| 9. | 57 | F | PSL | 5 | - | Recovery | |

| 10. | 39 | M | PSL | 5 | Acute lymphocytic leukemia | + | Recovery |

| 11. | 43 | M | PSL | 10 | - | Recovery | |

| Patients who did not receive early introduction of high-dose corticosteroids | |||||||

| 12. | 49 | F | PSL+IFN | 14 | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | + | Death |

| 13. | 59 | F | PSL | 14 | - | Death | |

| 14. | 47 | M | PSL+Lam | 14 | Ulcerative colitis | + | Death |

| 15. | 58 | M | PSL | 15 | - | Death | |

| 16. | 59 | M | PSL | 17 | - | Death | |

| 17. | 36 | F | MPSL/PSL+IFN | 28 | Breast cancer | + | Death |

| 18. | 68 | F | PSL | 120 | Pemphigoid | + | Death |

| 19. | 41 | M | glycyrrhizin | - | Recovery | ||

| 20. | 55 | M | glycyrrhizin | - | Recovery | ||

| 21. | 59 | M | glycyrrhizin | - | Death | ||

| 22. | 28 | M | glycyrrhizin | Mental retardation | - | Death | |

The remaining 11 patients were not treated with “early high-dose” corticosteroids (Table 1), because it was already 10 d before they were admitted to our unit.

Two patients (patients 1 and 17) with marked prolongation of PT were treated with 1000 mg of methylprednisolone daily for 3 d followed by the same pre-dnisolone therapy as described above. Two patients with deep hepatic coma at admission (patients 12 and 17) were treated with a combination therapy of corticosteroid and interferon. Interferon-β was administered at 3 million units/d. Afterwards, lamivudine, a nucleoside analogue with significant inhibition of HBV DNA polymerase, which could be used safely in patients with severe disease[12-17] was administered, in addition to prednisolone, at a daily dose of 150 mg in 3 patients, 2 in the “early high-dose” group (patients 6 and 7) and 1 in the “non-early high-dose” group (patient 14).

Four patients were treated with intravenous glycyrrhizin (stronger neominophagen C) at 60 mL/d, an aqueous extract of licorice root which is reported to have anti-inflammatory activity and has been used for the treatment of chronic viral hepatitis in Japan[18].

HBsAg, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), anti-HBe antibody (HBeAb), HBcAb, IgM-HBc, IgM anti-HAV antibody, and anti-hepatitis D antibody were detected by commercial radioimmunoassay (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL), and HCV RNA was measured by nested RT-PCR[19]. The second generation of anti-HCV anti-body was measured by enzyme immunoassay (Ortho Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan). IgM-EBV, IgM-CMV, and IgM-HSV were examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Anti-nuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-mitochondrial antibody, and anti-liver kidney microsomal-1 antibody were detected by fluorescent antibody method. HBV DNA polymerase was assayed according to the method of Kaplan et al[20]. HBV DNA level was measured by hybridization assay (Abbott) or branched DNA hybridization assay (Chiron, Emeryville, CA).

Differences among the groups were compared by Fisher’s exact probability test, Student’s t and Welch’s t.

Of the 22 patients fulfilling the criteria of “severe” exacerbation, 14 were men and 8 women. The mean age at the time of admission was 46.7±12.9 years. HBeAg/HBeAb status was +/- in 7, -/+ in 12, +/+ in 2, and -/- in 1. Seven patients had primary diseases (2 non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, 2 ulcerative colitis, 1 acute lymphocytic leukemia, 1 breast cancer, and 1 pemphigoid), and all 7 had been treated with immunosuppressive or cytotoxic drugs, suffering exacerbations after their withdrawal. Two patients had primary conditions, 1 with schizophrenia, and the other with mental retardation. Eleven patients were treated with “early high-dose” corticosteroids and 11 were not. The clinical, biochemical, and histological features of all patients at admission are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

| Pt | PT(%) | ALT(IU/L) | T-bili(mg/dL) | HBeAg/HBeAb | IgM-HBc(cut-off index) | HBV DNApolymerase (cpm) | HBV DNA(Meq/mL) | Liver histology |

| Patients who received early introduction of high-dose corticosteroids | ||||||||

| 1. | 16 | 1698 | 9.5 | -/+ | 2.6 | 10 | ND | ND |

| 2 | 31 | 2689 | 3 | +/- | 0.3 | 3517 | ND | ND |

| 3 | 57 | 474 | 15.2 | -/+ | 0.2 | 50 | <0.70 | ND |

| 4 | 37 | 495 | 12.0 | +/- | 0.3 | 999 | 920 pg/mL | CAH (F2, severe) |

| 5 | 37 | 155 | 8 | -/- | 0.5 | ND | 1+ | ND |

| 6 | 56 | 2080 | 4.2 | +/+ | 1.8 | 595 | <0.70 | CAH (F2, severe) |

| 7 | 57 | 167 | 3.1 | -/+ | ND | 6425 | ND | ND |

| 8. | 37 | 2257 | 3.7 | -/+ | 2.3 | 28 | 20 | CAH (F3, severe) |

| 9 | 34 | 224 | 7.3 | +/- | 1.4 | 25 | 1.2 | ND |

| 10 | 56 | 399 | 3.8 | -/+ | 3.7 | 11600 | ND | Submassive necrosis |

| 11 | 46 | 101 | 6.4 | -/+ | 0.3 | 10 | <0.70 | LC, submassive necrosis |

| Patients who did not receive early introduction of high-dose corticosteroids | ||||||||

| 12 | 29 | 254 | 12.6 | -/+ | 1.1 | 0 | <0.70 | ND |

| 13. | 34 | 2 643 | 19.3 | +/- | 1.6 | 0 | <0.70 | ND |

| 14. | 32 | 240 | 2.9 | -/+ | 0.5 | 12735 | 3800 | ND |

| 15 | 28 | 228 | 13.3 | -/+ | 3.3 | 16 | 1.1 | Submassive necrosis |

| 16. | 29 | 150 | 13.3 | -/+ | 0.2 | 53856 | >10000 | Submassive necrosis |

| 17 | 19 | 549 | 11.1 | +/- | 7.6 | 2 | 1.9 | LC, submassive necrosis |

| 18 | 28 | 954 | 6.3 | -/+ | ND | ND | ND | Submassive necrosis |

| 19. | 59 | 214 | 12.9 | +/+ | 0.4 | 5 | ND | CAH (F3, moderate) |

| 20 | 38 | 3620 | 7.7 | -/+ | 0.2 | 0 | <0.70 | CAH (F3, moderate) |

| 21. | 33 | 164 | 8.9 | +/- | ND | 7576 | ND | LC, submassive necrosis |

| 22. | 21 | 49 | 8.0 | +/- | 1.0 | 0 | <0.70 | Submassive necrosis |

The clinicopathological features of the “early high-dose” and “non-early high-dose” groups of patients at admission stage were compared (Table 2). There were no differences in mean age, male-to-female ratio, mean PT activity, mean ALT level, mean T-bili level, positivity of HBeAg, mean IgM-HBc titer and HBV DNA polymerase activity between two groups. Serum HBV DNA was positive in 4 of 7 “early high-dose” patients and in 4 of 8 “non-early high-dose” patients. The duration between the diagnosis of severe exacerbation and the introduction of corticosteroids or immunosuppressive drugs was 4.3±2.3 d in the “early high-dose” group, and 31.7±39.3 d in the “non-early high-dose” group (P = 0.11).

Ten of 11 patients were alive and well after treatment in the “early high-dose” group. Ten alive patients were free of hepatic encephalopathy during the course. One patient died of sepsis. In the “non-early high-dose” group, 2 patients recovered and 9 patients died (P<0.001). Eight patients died of hepatic failure and 1 (patient 22) of sepsis. Two patients (patients 12 and 17) had deep coma at admission, and neither responded to therapies including artificial liver support such as plasma exchange and hemodiafiltration. None of the remaining 9 patients had encephalopathy at admission, but 7 of them failed to respond to therapies and gradually developed hepatic failure.

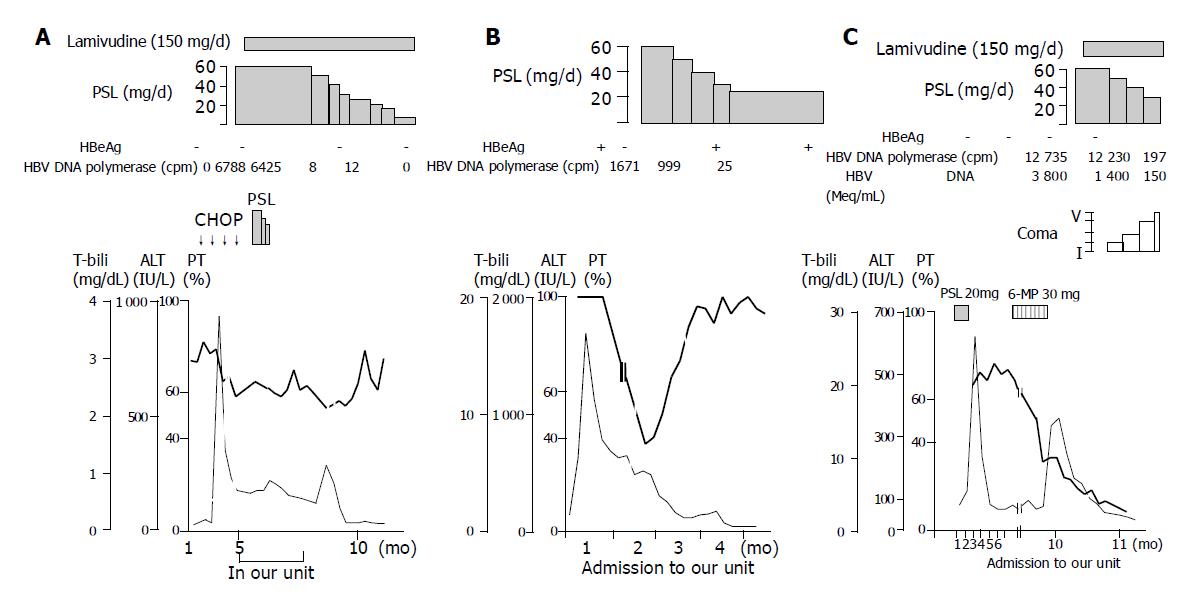

Changes in PT activities, ALT levels, T-bili levels, and HBV DNA polymerase activities after the introduction of corticosteroid therapy are shown in Figure 1. Improvement of PT activities was found in all but one (patient 7) of the “early high-dose” group. In patient 7 treated with corticosteroid and lamivudine, PT activities fluctuated and improvement was delayed by some months (Figure 2). In the “non-early high-dose” group, improved PT activities were obtained in 2 patients but not in the others, although some of them showed transient rise after infusions of fresh frozen plasma. The elevation of PT activities in the first 2 wk was significant (P = 0.006) in the “early high-dose” group, but not in the “non-early high-dose” group (Figure 1A).

The ALT levels fell in all 22 patients during the course, with the decline in the first 2 wk being significant (P<0.001) in both groups (Figure 1B). T-bili levels fell during the course in the “early high-dose” group, but rose in the “non-early high-dose” group (Figure 1C). HBV DNA polymerase activities fell in all the patients examined (Figure 1D). These results might indicate that the “early high-dose” introduction of corticosteroids could suppress the host immunologic reaction to HBV and inhibit significant liver cell degeneration.

Liver histology of 5 “early high-dose” patients showed submassive necrosis in 1, liver cirrhosis with submassive necrosis in 1, chronic hepatitis (F2, severe) in 2, and chronic hepatitis (F3, severe) in 1. Liver histology of 8 “non-early high-dose” patients showed submassive necrosis in 4, liver cirrhosis with submassive necrosis in 2, and chronic hepatitis (F3, moderate) in 2 (Table 2).

The prognosis of severe exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B is poor if signs of liver failure appear[1,2,21]. The mortality rate of chronic hepatitis B patients with severe exacerbation related to chemotherapy is reported to be 45% from Japan[2], and 60% from Slovenia[21]. If effective therapeutic approaches are available, they must be beneficial for these patients. In the current study, only one of the 11 (9%) “early high-dose” corticosteroid-treated patients died, whereas 9 of 11 (82%) “non-early high-dose” patients died (P<0.001), suggesting that “early high-dose” corticosteroid treatment is beneficial for clinically severe exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. Representatively, clinical course of one patient (patient 4) who recovered after treatment with only corticosteroid is demonstrated in Figure 2B.

Regarding the timing of corticosteroid treatment, Gregory et al[22] reported that methyl prednisolone cannot enhance survival in patients with severe “acute” viral hepatitis when used later, but they conceived that steroid would have likely proved beneficial if treatment had started “much earlier”. Actually, in our study, all the 7 patients died when high-dose corticosteroid was given more than 10 d after the diagnosis of severe disease, indicating the importance of the “early” usage of corticosteroid. When the start of treatment is delayed, quite a large number of hepatocytes would probably already have been destroyed and inhibition of the inflammatory reaction would not be effective.

Regarding the corticosteroid dosage, Schalm et al[23] demonstrated that histologically severe chronic active hepatitis B patients failing treatment with conventional doses of prednisone often improved with higher doses, suggesting that higher doses of steroid might be more efficacious. One of the reasons, for not using corticosteroids in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B, is that it might enhance the replication of HBV through a steroid-responsive element in the HBV genome[24]. In our study, serum HBV DNA at admission was negative in about half of our patients. Moreover, none of the patients, given high doses of corticosteroids, showed increments of HBV. Because of the rapid and aggressive immune clearance of virus-infected hepatocytes by CTL-mediated cytolytic pathways, patients developing a rapid course of liver- failure might not show evidence of HBV replication during the short-term observation period of the present study.

Our results indicate the importance of immunosuppressive therapy for preventing the progression of liver failure. If HBV proteins are not produced in hepatocytes, CTL will not recognize and destroy the HBV-infected hepatocytes. Therefore, suppression of the production of HBV-related proteins by preventing HBV replication must also be important in the treatment of severe exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B.

In a couple of cases, we administered lamivudine, an antiviral agent, in combination with corticosteroids. Lamivudine is a nucleoside analogue that has recently been used for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B, demonstrating a strong inhibitory effect on HBV replication. Several recent studies have reported that lamivudine appears to be effective in advanced and decompensated chronic liver disease and acute hepatic failure due to hepatitis B[12-17]. Therefore, lamivudine may be effective in the treatment of severe exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B.

With the administration of lamivudine, HBV DNA is reduced rapidly, but the improvement in liver-function is delayed by a few weeks to a few months[14]. During the time- lag phase, excessive immunological reaction may continue and liver cell injury may progress. We observed in a patient (patient 7) who needed more than 3 mo before the improvement of liver function became evident (Figure 2A), and a patient (patient 14) who died despite the usage of lamivudine (Figure 2C). The latter patient was an asymptomatic carrier of HBV with anti-HBe, and severe exacerbation of hepatitis occurred after the withdrawal of immunosuppressive drugs for ulcerative colitis. When admitted to our hospital, PT was already markedly prolonged (Figure 2C). It seems that anti-viral therapy is not enough to stop progressive deterioration, and additional therapy to suppress liver cell degeneration may be required. Combination treatment with “early high-dose” corticosteroids and lamivudine might be effective in suppressing the excessive host immune response in the early period. Additionally, lamivudine may make it possible to shorten the term of corticosteroid therapy. The efficacy of this combination therapy needs to be examined as soon as possible.

In summary, our study demonstrates that the early introduction of high-dose corticosteroid treatment is useful for “clinically severe” acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B; we did not include placebo-controlled patients, considering the current knowledge of the poor prognosis of such patients. The combination of corticosteroids with lamivudine may be a beneficial option for the treatment of such patients. Nevertheless, delay in the treatment may result in fatal liver- failure even though these treatment protocols are used, suggesting the requirement of early diagnosis of such patients, at the first sign of a biochemical trend of liver failure, before the appearance of clinical symptoms.

We thank Dr. Toshiki Ehata (Ehata Clinic, Unakami, Chiba) for clinical contributions.

| 2. | Nakamura Y, Motokura T, Fujita A, Yamashita T, Ogata E. Severe hepatitis related to chemotherapy in hepatitis B virus carriers with hematologic malignancies. Survey in Japan, 1987-1991. Cancer. 1996;78:2210-2215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chisari FV, Ferrari C. Hepatitis B virus immunopathogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:29-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1189] [Cited by in RCA: 1201] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hanson RG, Peters MG, Hoofnagle JH. Effects of immunosuppressive therapy with prednisolone on B and T lymphocyte function in patients with chronic type B hepatitis. Hepatology. 1986;6:173-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sjogren MH, Hoofnagle JH, Waggoner JG. Effect of corticosteroid therapy on levels of antibody to hepatitis B core antigen in patients with chronic type B hepatitis. Hepatology. 1987;7:582-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nouri-Aria KT, Hegarty JE, Alexander GJ, Eddleston AL, Williams R. Effect of corticosteroids on suppressor-cell activity in "autoimmune" and viral chronic active hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1301-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lam KC, Lai CL, Trepo C, Wu PC. Deleterious effect of prednisolone in HBsAg-positive chronic active hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:380-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hoofnagle JH, Davis GL, Pappas SC, Hanson RG, Peters M, Avigan MI, Waggoner JG, Jones EA, Seeff LB. A short course of prednisolone in chronic type B hepatitis. Report of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:12-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Scullard GH, Smith CI, Merigan TC, Robinson WS, Gregory PB. Effects of immunosuppressive therapy on viral markers in chronic active hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:987-991. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lau JY, Bird GL, Gimson AE, Alexander GJ, Williams R. Treatment of HBV reactivation after withdrawal of immunosuppression. Lancet. 1991;337:802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Katz R, Velasco M, Klinger J, Alessandri H. Corticosteroids in the treatment of acute hepatitis in coma. Gastroenterology. 1962;42:258-265. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Santantonio T, Mazzola M, Pastore G. Lamivudine is safe and effective in fulminant hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 1999;30:551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Van Thiel DH, Friedlander L, Kania RJ, Molloy PJ, Hassanein T, Wahlstrom E, Faruki H. Lamivudine treatment of advanced and decompensated liver disease due to hepatitis B. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:808-812. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Chan TM, Wu PC, Li FK, Lai CL, Cheng IK, Lai KN. Treatment of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis with lamivudine. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:177-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | ter Borg F, Smorenburg S, de Man RA, Rietbroek RC, Chamuleau RA, Jones EA. Recovery from life-threatening, corticosteroid-unresponsive, chemotherapy-related reactivation of hepatitis B associated with lamivudine therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2267-2270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ahmed A, Keeffe EB. Lamivudine therapy for chemotherapy-induced reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:249-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Villeneuve JP, Condreay LD, Willems B, Pomier-Layrargues G, Fenyves D, Bilodeau M, Leduc R, Peltekian K, Wong F, Margulies M. Lamivudine treatment for decompensated cirrhosis resulting from chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2000;31:207-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Iino S, Tango T, Matsushima T, Toda G, Miyake K, Hino K, Kumada H, Yasuda K, Kuroki T, Hirayama C. Therapeutic effects of stronger neo-minophagen C at different doses on chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2001;19:31-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Okamoto H, Okada S, Sugiyama Y, Tanaka T, Sugai Y, Akahane Y, Machida A, Mishiro S, Yoshizawa H, Miyakawa Y. Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA by a two-stage polymerase chain reaction with two pairs of primers deduced from the 5'-noncoding region. Jpn J Exp Med. 1990;60:215-222. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kaplan PM, Greenman RL, Gerin JL, Purcell RH, Robinson WS. DNA polymerase associated with human hepatitis B antigen. J Virol. 1973;12:995-1005. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Markovic S, Drozina G, Vovk M, Fidler-Jenko M. Reactivation of hepatitis B but not hepatitis C in patients with malignant lymphoma and immunosuppressive therapy. A prospective study in 305 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2925-2930. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Gregory PB, Knauer CM, Kempson RL, Miller R. Steroid therapy in severe viral hepatitis. A double-blind, randomized trial of methyl-prednisolone versus placebo. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:681-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schalm SW, Summerskill WH, Gitnick GL, Elveback LR. Contrasting features and responses to treatment of severe chronic active liver disease with and without hepatitis BS antigen. Gut. 1976;17:781-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tur-Kaspa R, Burk RD, Shaul Y, Shafritz DA. Hepatitis B virus DNA contains a glucocorticoid-responsive element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1627-1631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |