INTRODUCTION

Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) is the current treatment of surgical choice for ulcerative colitis and for selected familial adenomatous polyposis[1,2]. One of the main long-term complications after IPAA is inflammation of the pouch (pouchitis). Symptomatic inflammation of the ileal pouch develops in 7-40% of patients who undergo IPAA[3-6]. The etiology of pouchitis is probably a multifactorial event involving genetic, immune, microbial, and toxic mediators, but is poorly understood. Heusten first identified “secondary pouchitis” caused by surgical complication specific to the ileal reservoir and pouch anal anastomosis[7]. Most cases of pouchitis are primary with an acute course and show a good response to medical therapy, but patients with secondary pouchitis underlying surgical complications need surgical management because medical treatment alone is ineffective. In this report, we described a case of secondary pouchitis due to a peripouch abscess, blind loop formation, which had no response to medical treatment, and so we selected a surgical procedure suitable to the disease state.

CASE REPORT

This case was about a 20-year-old woman who had been diagnosed as having an ulcerative colitis when she was 12 years old. She had been controlled in remission with medical therapy (prednisone and 5-aminosalicylic acid), but on July 2001, she relapsed to severe colitis and was admitted in another hospital. She was treated there with intravenous fluids, broad spectrum parenteral antibiotics, systemic steroids (prednisone 60 mg/d), and granulocytapheresis (GCAP). Despite this conservative therapy, her condition deteriorated and she had underwent laparoscopic total colectomy, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and diverting ileostomy.

About 3 mo after the primary operation, she had episodes 10 times a day of continuous severe bloody diarrhea. Colonoscopy showed inflammatory mucosa spontaneously bleeding from the anal verge to the ileal J pouch; and was diagnosed as severe pouchitis. She received metronidazole in the form of enemas, but did not respond.

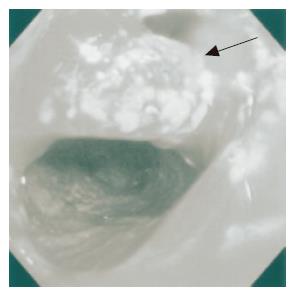

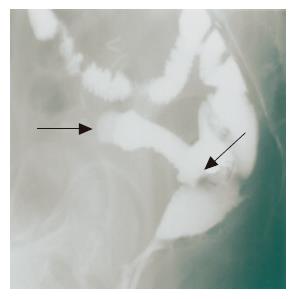

On admission to our hospital, she was not pale, afebrile with a pulse rate of 90 beats/min, and had an anal bloody mucus discharge of 5-10 times per day. Laboratory studies showed that all parameters were almost normal. Culture analysis of the bloody mucus discharge showed multiplication of streptococcus agalactiae and Gram-negative rods. Pouchoscopy showed easy bleeding, inflammatory mucosa with ulcer formation, apical bride formation in the ileal J pouch and edematous colonic mucosa with inflammation from the anal verge to the anastomosis (Figure 1). A pouchogram showed an about 10-cm blind loop formation of the ileal J pouch and apical bridge formation (Figure 2). Since we assumed that the operative procedures had not causally affected the outcomes, conservative therapy using metronidasole enemas, steroid enemas, and leukocytapheresis was undertaken for 1 mo.

Figure 1 Pouchoscopy shows inflamed hemorrhagic mucosa.

An apical bridge is seen (arrow head).

Figure 2 Pouchography shows a blind loop 10 cm in length (arrow head) and apical bridge formation (arrow).

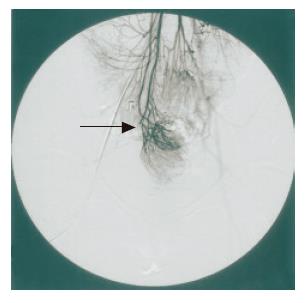

However, no improvement of clinical symptoms or endoscopic findings was obtained. We attempted to re-evaluate using more extensive examinations. Abdominal CT showed that bilateral ovarian cysts but no remarkable intrapelvic abscess was recognized. Superior mesenteric arterial angiography showed that the ileal J pouch was supplied from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the ileocolic artery (ICA), but that the arcades of these arteries were divided (Figure 3). These findings suggested that the pathogenesis of the disease was secondary pouchitis, due to abnormal formation of the ileal J pouch constructed apical bridge and blind loop or/and ischemic change of the pouch.

Figure 3 Superior mesenteric arteriography shows a marginal disconnection of the arcade (superior mesenteric artery–ileocolic artery) (arrow).

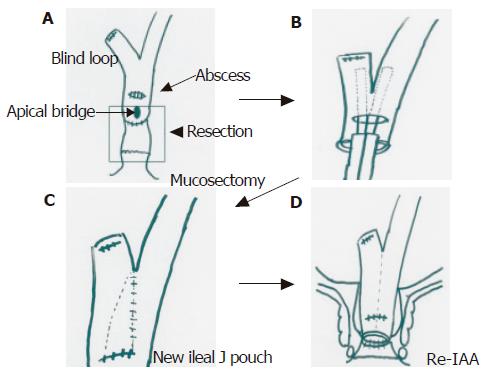

On 27 February 2002, she underwent laparotomy. At laparotomy, adhesion in the intra-abdominal space was recognized, but no ascites was seen. From the dentate line, rectal mucosectomy and ileal J pouch excision was performed at first. A peripouch abscess was recognized on the posterior wall of the pouch, and was tightly adhesive to the sacrum. Pouch mucosa on the site of the abscess had erosion and was partly deficient. We diagnosed secondary pouchitis due to a late peripouch abscess. We undertook abscess drainage, excision of the remnant rectum and ileal J pouch including the apical bridge. Side to side anastomosis of the blind loop was performed using a linear stapler into the site of the wall deficiency. After re-ileoanal anastomosis was performed, a covering ileostomy was constructed (Figures 4A-D).

Figure 4 A: Mucosectomy and ileal pouch excision; B: side to side anastomosis of blind loop by linear stapler; C: reconstruction of a new ileal pouch; D: re-ileal pouch anal anastomosis.

There was a sustained clinical improvement in the patient after this re-operation without any complications. She was discharged on March 25, 2002. Three months later, ileostomy closure was performed. She remains well, with no sign of pouchitis, and has complete continence with bowel movements, 5 times per day.

DISCUSSION

Pouchitis is a term coined by Kock[8] that described the reservoir ileitis that developed in a number of patients with ulcerative colitis who underwent continent ileostomy operations. In 1980, proctocolectomy with ileal reservoir and anal anastomosis was described by Parks[9] and this operation, when performed for ulcerative colitis, also produced pouchitis in a number of patients. The causes of the pouchitis have been poorly understood. Possible causes advanced include fecal stases resulting in bacterial overgrowth and infection[10], ischemia[11], oxygen free radical injury[12] and deprivation of short chain fatty acids[13].

Data on incidence and prevalence of pouchitis in the literature shows great disparities[14,15]. One reason for this disparity is related to the varying durations and modes of follow-up, the lack of a commonly accepted definition of pouchitis, and the lack of valid scoring for estimating the severity of inflammation[16-20]. Another reason is that pouchitis caused by surgical complication is not widely recognized. Heuschen[7] coined the term “secondary pouchitis” caused by surgical complication specific to the ileal reservoir and pouch-anal anastomosis. These surgical complications can cause clinical symptoms, such as an elevated frequency of defecation, hematochesia, fever, and malaise, which are very similar to those of idiopathic pouchitis. Nonspecific medical treatment of these symptoms as with primary pouchitis appears to be totally inadequate.

In our case, the patient had inflammatory changes in ileal J pouch mucosa with a defunctioned pouch. Pouch formation was abnormal with an apical pouch bridge[21] and an about 10-cm blind loop of the ileal pouch. Furthermore, medical treatment such as with metronidazole, topical steroids in the form of enemas, and GCAP were not effective. SMA angiography could suspect ischemic changes of the pouch mucosa because of the dividing of the arcades of SMA and ICA. However, a resected specimen (remnant rectum and ileal pouch) near the abscess formation showed extensive erosion and diffuse thickening. So we diagnosed that this secondary pouchitis was mainly caused by a peripouch abscess and was partly concerned with the abnormal pouch formation.

Moreover, crucial elements in our salvaged surgery were the initial resection of the peripouch abscess and the damaged portion of the pouch, and then the reconstruction of the pouch and re-IAA; thus improving hopes of curability.

In conclusion, salvage surgery might be indicated as a first choice treatment for secondary pouchitis caused by surgery-related complications. A surgical procedure suitable for the state of the disease should be selected after instituting a comprehensive series of examinations[22].