Published online Oct 14, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i38.6022

Revised: January 23, 2005

Accepted: January 26, 2005

Published online: October 14, 2005

AIM: To investigate retrospectively the clinical and endoscopic features of bleeding Dieulafoy's lesions and to assess the short- and long-term effectiveness of endoscopic treatment.

METHODS: Twenty-three patients who had gastrointestinal bleeding from Dieulafoy's lesions underwent endoscopic therapy. Demographic data, mode of presentation, risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding, blood transfusion requirements, endoscopic findings, details of endoscopic therapy, recurrence of bleeding, and mortality rates were collected and analyzed retrospectively.

RESULTS: Hemostasis was attempted by dextrose 50% plus epinephrine in 10 patients, hemoclipping in 8 patients, heater probe in 2 patients and ethanolamine oleate in 2 patients. Comorbid conditions were present in 17 patients (74%). Overall permanent hemostasis was achieved in 18 patients (78%). Initial hemostasis was successful with no recurrent bleeding in patients treated with hemoclipping, heater probe or ethanolamine injection. In the group of patients who received dextrose 50% plus epinephrine injection treatment, four (40%) had recurrent bleeding and one (10%) had unsuccessful initial hemostasis. Of the four patients who had rebleeding, three had unsuccessful hemostasis with similar treatment. Surgical treatment was required in five patients (22%) owing to uncontrolled bleeding, recurrent bleeding with unsuccessful retreatment and inability to approach the lesion. One patient (4.3%) died of sepsis after operation during hospitalization. There were no side-effects related to endoscopic therapy. None of the patients in whom permanent hemostasis was achieved presented with rebleeding from Dieulafoy’s lesion over a mean long-term follow-up of 29.8 mo.

CONCLUSION: Bleeding from Dieulafoy’s lesions can be managed successfully by endoscopic methods, which should be regarded as the first choice. Endoscopic hemoclipping therapy is recommended for bleeding Dieulafoy’s lesions.

- Citation: Katsinelos P, Paroutoglou G, Mimidis K, Beltsis A, Papaziogas B, Gelas G, Kountouras Y. Endoscopic treatment and follow-up of gastrointestinal Dieulafoy's lesions. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(38): 6022-6026

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i38/6022.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i38.6022

Dieulafoy's lesion was first described by Gallard in 1884 and later fully characterized by French surgeon George Dieulafoy in 1896, as an arterial lesion associated with massive gastric hemorrhage. It is described as a minute defect of the gastrointestinal mucosa with rupture of a large submucosal artery into the lumen. Although usually described in the stomach, Dieulafoy's lesions are also described in the rest of the gastrointestinal tract including esophagus[1-3] duodenum[4] small bowel[5] colon[6] rectum[7] and anus[8].

Until a few years ago, surgical treatment was advocated for such lesions because of the inability to recognize the lesion via endoscopy, or because of massive and recurrent bleeding. However, endoscopic therapy has recently become the treatment of choice by many endoscopists, being effective in the majority of cases[9]. The aim of our study was to assess the short- and long-term effectiveness of endoscopic treatment of Dieulafoy's lesions.

Between January 1994 and December 2003, 936 patients with acute GI bleeding of non-variceal origin were admitted to our endoscopy unit. After resuscitation with intravenous fluids and blood transfusions, emergency endoscopy without preparation was performed within 24 h of the onset of bleeding, using standard video-endoscopes. If there was fresh blood or clots obscuring bleeding lesion, a lavage with a large bore tube (34F) for upper GI bleeding or rigorous cleansing of the colon with polyethylene glycol solution was performed. ECG, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation were monitored. Twenty-three patients were diagnosed as having Dieulafoy's lesions.

The endoscopic diagnosis of Dieulafoy's lesions was based on the following established criteria: active arterial spurting or micropulsatile streaming from a minute (<3 mm) mucosal defect, visualization of a protruding vessel with or without active bleeding within a minute mucosal defect or normal surrounding mucosa or densely adherent clot with a narrow point of attachment to a minute mucosal defect or normal-appearing mucosa. To avoid possible inclusion of variceal bleeding at either the index episode of bleeding or an episode of recurrent bleeding, all patients with esophagogastric varices were excluded from the study. If Dieulafoy's lesion was diagnosed at emergency endoscopy according to the criteria outlined above, the choice of the endoscopic method of treatment was left to the endoscopist's discretion.

The therapeutic methods used in the first six years of our study were injection of a solution of dextrose 50% plus epinephrine (1:10 000) and ethanolamine oleate, while heater probe treatment and hemoclipping were used in the last 4 years. In the injection group, 1 mL aliquot was injected via a plastic cannula (23-gauge, 5-mm tip) into and around the Dieulafoy’s lesion. A limit of 10 mL of mixture per endoscopic session was set. A 3.2 mm diameter heater probe set at 30 J/pulse was used to coat the bleeding vessel. Hemoclip therapy (HX-3L, 5LR-1; Olympus Optical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was performed by mechanical clipping of spurting, oozing or visible vessels.

Therapeutic endoscopy was defined as successful if there was no further bleeding from the Dieulafoy's lesion until the withdrawal of the endoscope. After endoscopic treatment, the patients with Dieulafoy's lesion in the upper GI tract were treated with intravenous administration of a standard dose of PPIs. Follow-up endoscopy was performed within 24 h after the initial procedure and at least once within 5 d. Criteria for recurrent bleeding included fresh hematemesis or hematochezia, fresh blood aspirated through the nasogastric tube, instability of vital signs or a reduction of hemoglobin in excess of 30 g/L within 24 h after endoscopic hemostasis. When recurrent bleeding was suspected, immediate endoscopic retreatment was performed. If bleeding persisted after the second intervention, an operation was performed. In order to determine whether new bleeding episodes occurred after discharge, long-term follow-up was carried out by retrieving the medical records from the files, and when necessary by telephone calls to the patients. The patients who underwent surgery were not subjected to long-term follow-up.

Data including age, gender, comorbidities, mode of presentation, hemodynamic parameters, blood transfusion requirements before and after endoscopic therapy, risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding (such as coagulopathy, use of aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), endoscopic findings, details of endoscopic therapy, complications, recurrence of bleeding, and 30-d mortality were collected (Table 1).

| N | Sex | Age | Location | Bleeding symptom | Hb g/L | Transfusion (RBC) | Medical history | Endoscopic picture of bleeding | Type of therapy | Hemostasis | Rebleeding | Outcome |

| 1 | F | 84 | Fundus | Melena | 98 | 3 | Heart failure, hypertension | Oozing | Dextrose 50%+EPI (7 cm3) | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 2 | F | 54 | Upper gastric body | Hematemesis/melena | 117 | 1 | – | Spurting | Dextrose 50%+EPI (6 cm3) | Failure | – | Operation |

| 3 | F | 42 | Rectum | Rectal bleeding | 121 | – | – | Oozing | Dextrose 50%+EPI (7 cm3) | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 4 | M | 72 | Jejunum | Hematemesis/melena | 96 | 3 | Hypertension, angina | Visible vessel | Dextrose 50%+EPI (7 cm3) | Successful | Yes | Operation/death |

| 5 | M | 48 | Descending duodenum | Melena | 117 | – | – | Visible vessel | Dextrose 50%+EPI (8 cm3) | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 6 | M | 69 | Gastric body | Hematemesis/melena | 78 | 8 | Angina, BII gastrectomy | Spurting | Dextrose 50%+EPI (9 cm3) | Successful | Yes | Operation/discharge |

| 7 | M | 86 | Upper gastric body | Melena | 104 | 2 | Hypertension, Angina | Visible vessel | Dextrose 50%+EPI (7 cm3) | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 8 | F | 81 | Fundus | Melena | 87 | 4 | Hypertension, heart failure | Oozing | Dextrose 50%+EPI (8 cm3) | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 9 | M | 82 | Fundus | Hematemesis/melena | 78 | 8 | Heart failure | Visible vessel | Dextrose 50%+EPI (8 cm3) | Successful | Yes | Operation/discharge |

| 10 | M | 83 | Gastric body | Hematemesis/melena | 96 | 3 | Heart failure | Visible vessel | Dextrose 50%+EPI (8 cm3) | Successful | Yes | Discharge |

| 11 | F | 72 | Fundus | Melena | 77 | 6 | Hypertension | Visible vessel | Ethanolamine oleate (9 cm3) | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 12 | M | 66 | Upper gastric body | Melena | 106 | 2 | Gout, hypertension | Visible vessel | Ethanolamine oleate (6 cm3) | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 13 | M | 79 | Upper gastric body | Melena | 92 | 4 | Hypertension, angina | Visible vessel | EPI+HP (8´30 J) | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 14 | M | 74 | Fundus | Hematemesis/melena | 98 | 3 | Renal failure, gout, diabetes | Visible vessel | EPI+HP (6´30 J) | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 15 | M | 48 | Antrum | Melena | 110 | 1 | – | Oozing | EPI+3 hemoclips | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 16 | M | 60 | Antrum | Hematemesis/melena | 104 | 3 | Duodenal ulcer | Oozing | EPI+4 hemoclips | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 17 | M | 65 | Antrum | Melena | 103 | 2 | Diabetes, hypertension | Spurting | EPI+3 hemoclips | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 18 | M | 67 | Sigmoid colon | Rectal bleeding | 115 | 2 | Colonic polyps | Oozing | EPI+4 hemoclips | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 19 | M | 74 | Sigmoid | Rectal bleeding | 113 | 2 | Angina | Oozing | EPI+3 hemoclips | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 20 | M | 84 | Fundus | Hematemesis/melena | 88 | 4 | Heart failure, aorto-iliac bypass | Two visible vessels | 4 hemoclips | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 21 | F | 79 | Gastric body | Melena | 118 | 1 | Hypertension | Visible vessel | 2 hemoclips | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 22 | M | 75 | Gastric body | Melena | 103 | 2 | Heart failure | Visible vessel | 2 hemoclips | Successful | No | Discharge |

| 23 | M | 72 | Gastric body | Hematemesis/melena | 100 | 3 | BII gastrectomy angina | Visible vessel | Inability to approach the visible vessel | – | – | Operation/discharge |

Informed consent was obtained from the patients and/or their relatives. Because this study was a retrospective review, institutional review board approval was not necessary.

Studen’s t-test was utilized to compare the mean values of continuous variables and Fisher exact test was utilized for the comparison of discrete variables.

The study group consisted of 17 male (74%) and 6 female (26%) patients. The mean age was 70.26 years (range 42-84 years). There was a history of hypertension in nine patients, ischemic heart disease in four, heart failure in six, diabetes in two, gout in two, chronic renal failure in one, BII gastrectomy in two, duodenal ulcer in one, and aorto-iliac bypass in one (Table 1).

Melena was present in 11 patients (47.8%), hematemesis and melena in 9 (39%), and rectal bleeding in the remaining 3 patients (13.2%). Mean hemoglobin concentration was 101 g/L (normal 130-160 g/L). Blood transfusion requirements ranged from 1 to 8 U of packed RBC (mean 2.9 U per patient) during hospitalization. There was no significant difference with respect to coagulation parameters in patients who had recurrent bleeding and those who did not.

The Dieulafoy's lesions were located in the stomach in 18 patients (78%, fundus in 6, body in 9, and antrum in 3), in the colon in 3 (Figure 1), in the jejunum in 1 and in the descending duodenum in 1 (Table 1). Eleven patients (47.8%) had active bleeding (oozing in 7 and spurting in 4) at the initial endoscopy. In the remaining 12 patients (52.2%), a non-bleeding vessel was found (Table 1). In a 84-year-old patient with a medical history of heart failure and aorto-iliac bypass, endoscopy revealed two simultaneous Dieulafoy's lesions in the fundus, 2 cm apart. The initial endoscopy was diagnostic in 69% of patients. The mean number of endoscopies required for diagnosis was 1.7 (range 1-3). Failure to diagnose when the appropriate site was evaluated at endoscopy was due to excessive blood on 11 occasions (47.8%) and a missed lesion on 8 occasions (34.7%).

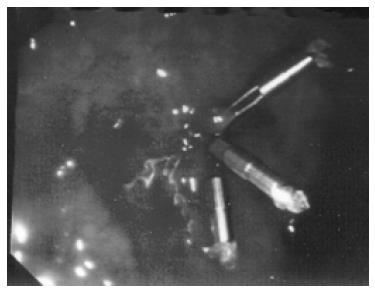

Ten patients were treated with dextrose 50% plus epinephrine 1:10 000 injection. Mean injection volume was 7.6 mL (range 6-9 mL). Initial hemostasis was achieved in nine patients (90%), but four patients (44%) had rebleeding, which was successfully controlled at repeat endoscopy in one patient, but not in the other three using similar therapy, and surgical intervention was required (Table 1). Four patients were treated with injection of ethanolamine oleate and the heater probe respectively, and permanent hemostasis was achieved on a single session (Table 1). The power settings for the heater probe were clearly stated in two patients (30 J in both) and the number of applications ranged from 6 to 8. Among the patients in the hemoclip group, the mean number of hemoclips used was 3.1 (range 2-4). Hemostasis was achieved at the initial endoscopic procedure by hemoclip (Figure 2) in all eight patients. Epinephrine plus normal saline (1:10 000) was used as an useful adjunct when the lesion was oozing or spurting, to slow or stop bleeding prior to hemoclip application or heater probe treatment. Five patients (22%) underwent surgery, four after unsuccessful endoscopic therapy and one because it was impossible to approach the lesion on the posterior wall of the patient's gastrectomized stomach. One patient (4.3%) died of sepsis and multiple organ failure in the postoperative period.

Endoscopic hemoclipping therapy was shown to be generally more effective than injection therapy in terms of the rates of permanent hemostasis (100% vs 66.6%,P<0.01), recurrent bleeding (0% vs 33.3%, P<0.01) and surgery (0% vs 33.3%, P<0.01, Table 2).

| Parameters | Injection group | Mechanical group | P |

| Initial hemostasis | 11 (92.5) | 8 (100) | ns |

| Recurrent bleeding | 4 (33.3) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| Permanent hemostasis | 8 (66.6) | 8 (100) | <0.01 |

| Operation | 4 (33.3) | 0 (0) |

In the five patients, who underwent surgery, gastrotomy showed a muscular artery protruding from the mucosa but not ulceration, findings being consistent with Dieulafoy's lesion. Wedge resection was performed and histopathologic examination confirmed the presence of an abnormally large submucosal artery.

None of the patients presented with recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding from Dieulafoy's lesions during a mean long-term follow-up of 29.8 mo (range 2-120 mo). Seven patients died during the follow-up from causes unrelated to the Dieulafoy's lesions or endoscopic procedures.

Dieulafoy's lesion is an uncommon cause of gastrointestinal bleeding, although some authors consider it as an under-recognized entity[1,9]. It is a disease of mainly aged and elderly males[10,11]. Our results with a mean age of 70.3 years and a more pronounced male predominance of 1:3 are consistent with former findings. Though the fact that they have been described in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, Dieulafoy's lesions are located in the proximal stomach in more than three-fourths of patients[1,2]. Accordingly, in 78% of our patients the lesion was found in the stomach and in 39% in the classic site within 6 cm of the gastroesophageal junction. As in other reports, we identified Dieulafoy's lesions in the colon, jejunum and duodenum. Interestingly, one patient presented two simultaneous Dieulafoy's lesions in the gastric fundus.

The diagnostic yield of the first endoscopy varies from 63% to 92%[9]. Norton et al[12] and Kasapidis et al[13] found that a mean of 1.9 or 1.3 endoscopic sessions is required for diagnosis. In the present study, the diagnosis of Dieulafoy's lesion was established in 69% of patients during the first endoscopy, with a mean of 1.7 endoscopic sessions. A protruding vessel is found in 50% of patients and about two-thirds of patients manifest active bleeding, either as oozing or as spurting[10,11,14,15]. By contrast, in the present study the frequency of active bleeding was low (39%), with the majority of our patients having a non-bleeding visible vessel (61%), though the fact that the comorbid conditions and the mean age of our patients were consistent with former studies.

Some investigators have documented significant diseases in patients with Dieulafoy's lesion[5,10,16,17]. Comorbidity of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic renal failure and hypertension is present in almost 90% of patients with Dieulafoy's lesion[12]. In more than 40% of patients with Dieulafoy's lesion, the use of medication that influences blood coagulation has also been noted[12,16]. However, other studies have found no association of Dieulafoy's lesion with concomitant disease or the use of medications[14,18]. The results of the present investigation are consistent with the former studies. The significant comorbidity in 17 patients (74%) is likely a reflection of the elderly population studied, since any pathogenic significance remains speculative. Pathologic studies have failed to demonstrate atherosclerosis or aneurismal dilatation of the involved vessel[16,18].

Surgical wedge resection has been the standard treatment of Dieulafoy's lesions in the past[1]. However, its mortality rate is as high as 23%[1]. Since the late 1980s, a variety of endoscopic techniques have been used in the management of Dieulafoy's lesions. Endoscopic hemostatic methods could be divided into three groups: thermal, regional injection and mechanical[9,12,17,19,20]. Each method has both advantages and disadvantages related to the hemostatic mechanism and the technical procedure itself and varying results have been reported. The results of endoscopic hemostatic therapies depend on many and variable factors. The major factors include the level of expertise in performing the endoscopic procedure, coincident clinical risk factors, the use of advanced equipment and the inherent differences in various procedures.

All these factors influence the success of endoscopic outcome, but endoscopic modalities can achieve permanent hemostasis in approximately 95% of patients[9]. The overall lower rate of permanent hemostasis (78%) in our study was due to the low hemostatic effect (60%) of dextrose 50% plus epinephrine injection. It must be emphasized that the osmotic dehydrating and sclerosant effect of hypertonic glucose water (50%) has been reported[21] to be superior than a classic sclerosant agent, like sodium tetradecyl sulfate (15%), in controlling bleeding and rebleeding in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis and gastric variceal bleeding. Therefore, the low rate of hemostasis achieved in our study by dextrose 50% plus epinephrine cannot be explained. A careful search of the MEDLINE database from 1970 to 2003 did not retrieve any report of dextrose 50% plus epinephrine used in the treatment of Dieulafoy's lesions. Thus, the present study seems to be the first report on the use of dextrose 50% plus epinephrine as a therapeutic modality for Dieulafoy's lesions.

In the present investigation, none of the patients treated with heater probe coagulation or ethanolamine oleate injection developed recurrent bleeding. The mechanical method of hemoclips used in our study achieved complete hemostasis in 100% of patients. None of our patients treated with hemoclips had recurrent bleeding, while four patients (33.3%) in the injection group had recurrent bleeding (P<0.01, Table 2).

Although the number of patients in our study was small, we believe that the successful management especially by hemostatic clips (Table 2) favors a primary endoscopic approach to Dieulafoy's disease. It must be underscored, however, that an experienced endoscopist is necessary as a Dieulafoy's lesion can easily be overlooked or may be difficult to be approached, as was the case for one of our patients.

Hemoclips are mechanical devices, it must be argued that they cannot eradicate a Dieulafoy's lesion with a large caliber artery as effectively as sclerosant injections or thermal coagulation and that bleeding may recur after this type of treatment. However, in our study no patient had recurrent bleeding after hemoclip treatment during the follow-up period.

In conclusion, endoscopic therapy has become the treatment of choice for Dieulafoy's lesions and the endoscopic hemoclip treatment is effective and appears to be more successful in achieving hemostasis than injection treatment. More definite conclusions require further large controlled studies.

Science Editor Wang XL and Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Fockens P, Tytgat GN. Dieulafoy's disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:739-752. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Reilly HF, al-Kawas FH. Dieulafoy's lesion. Diagnosis and management. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1702-1707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ertekin C, Barbaros U, Taviloglu K, Guloglu R, Kasoglu A. Dieulafoy's lesion of esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Goldenberg SP, DeLuca VA, Marignani P. Endoscopic treatment of Dieulafoy's lesion of the duodenum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:452-454. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gadenstätter M, Wetscher G, Crookes PF, Mason RJ, Schwab G, Pointner R. Dieulafoy's disease of the large and small bowel. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:169-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nozoe T, Kitamura M, Matsumata T, Sugimachi K. Dieulafoy-like lesions of colon and rectum in patients with chronic renal failure on long-term hemodialysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:3121-3123. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kayali Z, Sangchantr W, Matsumoto B. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to Dieulafoy-like lesion of the rectum. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:328-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Azimuddin K, Stasik JJ, Rosen L, Riether RD, Khubchandani IT. Dieulafoy's lesion of the anal canal: a new clinical entity. Report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:423-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Savides TJ, Jensen DM. Therapeutic endoscopy for nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000;29:465-87, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stark ME, Gostout CJ, Balm RK. Clinical features and endoscopic management of Dieulafoy's disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:545-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schmulewitz N, Baillie J. Dieulafoy lesions: a review of 6 years of experience at a tertiary referral center. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1688-1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Norton ID, Petersen BT, Sorbi D, Balm RK, Alexander GL, Gostout CJ. Management and long-term prognosis of Dieulafoy lesion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:762-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kasapidis P, Georgopoulos P, Delis V, Balatsos V, Konstantinidis A, Skandalis N. Endoscopic management and long-term follow-up of Dieulafoy's lesions in the upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:527-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Bartelsman JF, Schipper ME, Tytgat GN. Recurrent massive haematemesis from Dieulafoy vascular malformations--a review of 101 cases. Gut. 1986;27:213-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mumtaz R, Shaukat M, Ramirez FC. Outcomes of endoscopic treatment of gastroduodenal Dieulafoy's lesion with rubber band ligation and thermal/injection therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:310-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Juler GL, Labitzke HG, Lamb R, Allen R. The pathogenesis of Dieulafoy's gastric erosion. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79:195-200. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Parra-Blanco A, Takahashi H, Méndez Jerez PV, Kojima T, Aksoz K, Kirihara K, Palmerín J, Takekuma Y, Fuijta R. Endoscopic management of Dieulafoy lesions of the stomach: a case study of 26 patients. Endoscopy. 1997;29:834-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Katz PO, Salas L. Less frequent causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993;22:875-889. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Baettig B, Haecki W, Lammer F, Jost R. Dieulafoy's disease: endoscopic treatment and follow up. Gut. 1993;34:1418-1421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chung IK, Kim EJ, Lee MS, Kim HS, Park SH, Lee MH, Kim SJ, Cho MS. Bleeding Dieulafoy's lesions and the choice of endoscopic method: comparing the hemostatic efficacy of mechanical and injection methods. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:721-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chang KY, Wu CS, Chen PC. Prospective, randomized trial of hypertonic glucose water and sodium tetradecyl sulfate for gastric variceal bleeding in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis. Endoscopy. 1996;28:481-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |