Published online Oct 7, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i37.5828

Revised: February 15, 2005

Accepted: February 18, 2005

Published online: October 7, 2005

AIM: To investigate whether NSAIDs/ASA lesions in the colon can histologically be diagnosed on the basis of ischemic necrosis similar to biopsy-based diagnosis of NSAIDs/ASA-induced erosions and ulcers of the stomach.

METHODS: In the period between 1997 and 2002, we investigated biopsy materials obtained from 611 patients (415 women, 196 men, average age 60.5 years) with endoscopic focal erosions, ulcerations, strictures or diaphr-agms in the colon. In the biopsies obtained from these lesions, we always established the suspected diagnosis of NSAID-induced lesions whenever necroses of the ischemic type were found. Together with the histological report, we enclosed a questionnaire to investigate the use of medication. The data provided by the questionnaire were then correlated with the endoscopic findings, the location, number and nature of the lesions, and the histological findings.

RESULTS: At the time of their colonoscopy, 86.1% of the patients had indeed been taking NSAID/ASA medication for years (43.9%) or months (29.5%). The most common indication for the use of these drugs was pain (64.3%), and the most common indication for colonoscopy was bleeding (55.5%). Endoscopic inspection revealed multiple erosions and/or ulcers in 60.6%, strictures in 15.8%, and diaphragms in 3.0% of the patients. The lesions were located mainly in the right colon including the transverse colon (79.9%). A separate analysis of age and sex distribution, endoscopic and histological findings for NSAIDs alone, ASA alone, combined NSAID/ASA, and for patients denying the use of such drugs, revealed no significant differences among the groups.

CONCLUSION: This uncontrolled retrospective study based on the histological finding of an ischemic necrosis shows that the histologically suspected diagnosis of NSAID-induced lesions in the colon is often correct. The true diagnostic validity of this finding and the differentiation from ischemic colitis should, however, be investigated in a prospective controlled study.

- Citation: Stolte M, Karimi D, Vieth M, Volkholz H, Dirschmid K, Rappel S, Bethke B. Strictures, diaphragms, erosions or ulcerations of ischemic type in the colon should always prompt consideration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced lesions. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(37): 5828-5833

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i37/5828.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i37.5828

The first publications of NSAID-induced strictures in the small bowel[1,2] and colon[3,4] were followed by a number of reports that the intake of NSAIDs leads not only to such pathological changes as chemically-induced reactive gastritis, subepithelial bleeding, erosions and ulcerations complicated by bleeding or perforation in the stomach and duodenum[5,6], but also to erosions, ulcerations, perforations, bleeding[12,13,17], strictures and symptomatic diverticular disease[14-16] in the small and large bowel[7-11]. In animal experiments, it has been shown that as little as a single dose of NSAIDs can result in a high incidence of mortality after 3 d due to intestinal lesions and perforations[18-20].

With regard to the incidence of NSAID-induced lesions in the ileum and colon, the literature contains no reports on data obtained from controlled prospective endoscopic or endoscopy/biopsy studies. From the large Arthritis, Rheumatism, and Ageing Medical Information System databank of arthritic patients, however, it can be seen that 32% of gastrointestinal (GI) hospitalizations in osteoarthritis patients, and 13% of GI hospitalizations of patients with rheumatoid arthritis are due to lower GI diagnosis. In addition, studies of patients with spondyloarthropathy receiving conventional NSAID treatment over the long term have shown that 30-70% of these patients developed a macroscopic or microscopic ileitis, and, with varying frequency, inflammation of the cecum or colon[22-24].

In a post hoc analysis of 8 076 patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were treated with a non-selective NSAID (naproxen) or coxib (rofecoxib), serious lower intestinal events (bleeding, perforation, obstruction, ulceration, and diverticulitis) were found. The rate of events per 100 patient years was 0.41 for rofecoxib and 0.89 for naproxen. Serious lower GI events accounted for 39.4% of all serious GI events among patients taking naproxen, and 42% among those taking rofecoxib[25].

NSAIDs preparations not only inhibit prostaglandin synthesis via COX inhibition[26], but also uncouple mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation[27]. These substances also cause local topical toxicity[28], since they are lipid-soluble weak acids that can lead to interaction with surface membrane phospholipids and thus disruption of the gastric epithelial cell barrier and to back diffusion of acid into the mucosa[29,30].

Mucosal injuries in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) are also a consequence of NSAID-induced liberation of vasoc-onstricting leukotrienes[31,32], free radicals, platelet thrombi and proteases[33,34,36]. Other publications have demonstrated a connection between NSAID-induced microcirculatory disorders and the adhesion of neutrophil granulocytes to vascular endothelium. In addition, liberation of TNF-a is triggered, which is responsible for the liberation of the intracellular adhesion molecule-1 at the vessel walls, and which can lead to local microcirculatory disorders due to vascular spasms[35,37]. All these synergistic interactions[38,39], particularly the microcirculatory disorders caused by spasms of the tiny blood vessels, can give rise to ischemic erosions and ulcerations in the GIT[40-44] and to diaphragm-like strictures[46,48-51]. Since these lesions may be the cause of blood in the stools or a positive hemoccult test, and the bleeding may lead to chronic hemorrhagic anemia[45,54], the indication for colonoscopy is now being established more frequently in this group of patients. Since colonoscopic biopsies are always taken from macroscopically identifiable lesions, the question arises as to whether the pathologist can establish a suspected diagnosis of NSAID-induced lesions in the biopsy material, and how reliable this suspected diagnosis is. Having already shown that NSAID-induced erosions[52] and ulcerations[56] of the gastric mucosa can often be identified on the basis of necrosis of the ischemic type, we have now examined the question whether this type of necrosis might not also be a suitable diagnostic criterion for NSAID-induced lesions in the colon.

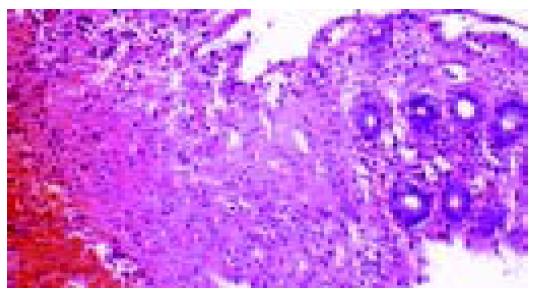

From 1997 to 2002, we investigated biopsy materials obtained from 611 patients (415 women, 196 men, average age 60.5 years) with focal erosions, ulcerations, strictures or diaphragms at endoscopy. In the biopsies obtained from these lesions, we always established the suspected diagnosis of NSAID-induced lesion whenever necroses of the ischemic type were found (homogeneous cell-poor eosinophilic necroses) to merge imperceptibly into the lamina propria (Figures 1 and 2), and when the clinical and endoscopic pictures and the location of the lesions militated against ischemic colitis. Together with the histological report, we enclosed a questionnaire with the aim of establishing the patient’s use of medication (Table 1). The data provided by the questionnaire were subsequently correlated with the endoscopic findings, localization, number and nature of the lesions, and the histological findings.

| Use of NSAID/ASA | Yes/no |

| If yes, which drug:............................ | |

| - What dose……………………… | |

| - How long……………………….. | |

| Indication for NSAID/ASA…………....... | |

| Indication for colonoscopy…………….. |

An analysis of the information provided on NSAID/ASA ingestion by the 501 patients with a histologically suspected diagnosis of NSAID/ASA-induced lesion in the colon is presented in Table 2 and shows that 86.1% of those patients actually were on NSAID/ASA medication at the time of their colonoscopy. In most cases, NSAIDs had been used for a period of years or months (Table 3). The most common indication for the use of these drugs was pain (Table 4). The symptoms that had led to an indication for colonoscopy are shown in Table 5. Lumping together the symptoms melena and anemia, and the positive occult blood test, it can be seen that bleeding complications occur in 55.5% of the cases, and are the most common indication for colonoscopy.

| D | 4.6 |

| Wk | 13.9 |

| Mo | 21.5 |

| Yr | 43.9 |

| No information | 16.1 |

| Pain | 64.3 |

| Polyarthritis | 12.3 |

| Coronary heart disease | 10.2 |

| Peripheral occlusive arterial disease | 7.9 |

| Others | 5.7 |

| Melena | 23.9 |

| Positive occult blood test | 11.0 |

| Anemia | 21.6 |

| Diarrhea | 19.4 |

| Abdominal pain | 17.7 |

| Weight loss | 1.9 |

| Ileus or subileus | 1.1 |

| Others | 1.1 |

The most commonly cited medication (70.5%) was diclofenac (Table 6). In 60.6% of the cases, endoscopy revealed multiple lesions (erosions or ulcers), strictures (15.8%), while diaphragm-like formations (3.0%) were relatively rare. The distribution of the location of these lesions identifies the right colon, in particular Bauhin’s valve, as the most frequently affected site (Table 7).

| Diclofenac | 70.5 |

| Ibuprofen | 7.3 |

| Piroxicam | 1.4 |

| Ketoprofen | 0.4 |

| Phenylbutazone | 0.2 |

| Combinations | 17.6 |

| Ileum | 4.5 |

| Bauhin’s valve | 21.3 |

| Cecum | 14.8 |

| Ascending colon | 19.1 |

| Right flexure | 7 |

| Transverse colon | 15.7 |

| Left flexure | 2.8 |

| Descending colon | 6.7 |

| Sigmoid colon | 5.3 |

| Rectum | 2.8 |

An analysis of the frequency of the various lesions in terms of solitary or multiple lesions showed that multiple lesions were most commonly ulcers or ulcers in combination with erosions, while solitary lesions were mostly focal erosions. Strictures or diaphragms were also frequently associated with multiple lesions (Table 8).

| Solitary | Multiple | |

| (n = 207) | (n = 319) | |

| (%) | (%) | |

| Erosions | 63.3 | 21.3 |

| Ulcers | 21.7 | 56.4 |

| Erosions+ulcers | 0 | 12.2 |

| Regenerative mucosa | 15 | 10.1 |

| Strictures | 11.1 | 18.8 |

| Diaphragms | 1.0 | 4.4 |

A separate analysis of patient’s age and sex distribution and endoscopic findings, after dividing cases into those with NSAID use alone, ASA use alone, combined use of NSAID and ASA, and cases denying NSAID/ASA intake, are shown in Table 9. A similar analysis of the histological findings is shown in Table 10. These two analyses revealed no statistically significant differences among the four groups of patients.

| n | F:M | Age (yr) | Locationright colon | Endoscopicsolitary lesion | Endoscopicmultiple lesions | Endoscopicstricture | Endoscopicdiaphragm | |

| 356 | 251:105 | 63±35 | 71.2% | 36.80% | 63.2% | 15.40% | 3.6% | |

| NSAID | 58.3% | 2.4:1 | 28-98 | n = 131 | n = 225 | n = 55 | n = 13 | |

| 122 | 75:47 | 56.5±33.5 | 76.8% | 50% | 50% | 12.30% | 0.8% | |

| ASA | 20% | 1.6:1 | 23-90 | n = 61 | n = 61 | n = 15 | n = 1 | |

| 48 | 39:9 | 68±21 | 80.8% | 31.2% | 68.8% | 25% | 2.10% | |

| NSAID+ASA | 7.8% | 4.3:1 | 47-89 | n = 15 | n = 33 | n = 12 | n = 1 | |

| 85 | 50:35 | 54.5±35.5 | 75.60% | 68% | 31.8% | 8.20% | 1.2% | |

| No NSAID/ASA | 13.9% | 1.4:1 | 19-90 | n = 58 | n = 27 | n = 7 | n = 1 |

| Solitaryerosion | Solitaryulcer | Solitaryregenerativemucosa | Multipleerosions | Multipleulcers | Multipleerosions+ulcers | Multipleregenerativemucosa | |

| NSAID (%) | 23.7 | 76.3 | 13 | 36.5 | 46.6 | 10.8 | 6.1 |

| n = 27 | n = 8 | n = 17 | n = 101 | n = 129 | n = 30 | n = 17 | |

| ASA (%) | 26.2 | 55.7 | 14.8 | 26.2 | 51 | 9.7 | 13.1 |

| n = 16 | n = 34 | n = 9 | n = 16 | n = 32 | n = 6 | n = 8 | |

| NSAID+ASA(%) | 26.6 | 66.6 | 6.8 | 21.2 | 57.6 | 15.2 | 6 |

| n = 4 | n = 10 | n = 1 | n = 7 | n = 19 | n = 5 | n = 2 | |

| No | 27.6 | 65.6 | 3.4 | 25.9 | 59.3 | 3.7 | 11.1 |

| No NSAID/ASA | |||||||

| (%) | n = 16 | n = 38 | n = 2 | n = 7 | n = 16 | n = 1 | n = 3 |

Our analysis showed that the histologically established diagnosis of suspected NSAID/ASA-induced lesion of the colonic mucosa is probably correct in a high percentage of cases (86.1%), and focal lesions were found, mainly in the right colon, such as Bauhin’s valve, cecum and ascending colon. However, since our study was an uncontrolled retrospective study based on histological findings, the results must be considered preliminary, and needs to be checked in prospective studies.

The topographic clustering of the lesions at Bauhin’s valve, in the cecum and ascending colon prompts the hypothesis that the lesions are not very likely caused by a generalized, but by a topical local injurious effect of the NSAID/ASA preparations. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that these lesions were, in many cases, associated with the use of retard preparations, and that in particular the “bottleneck” at Bauhin’s valve was involved. In those patients using non-retard preparations, it might be interesting to establish whether diarrhea associated with rapid transit of the medication into the colon was present. This point would have to be clarified in a prospective study, since we did not request information about a temporal relationship to diarrhea and the use of the medication. In support of a topical mucosa-injuring effect of NSAID/ASA, there are also numerous case reports on the use of retard preparations and on the preferential sites of the lesions in the right colon[42,44,50,51,53].

An unclear finding of our analysis that appeared surprising at first sight was the relatively high percentage of patients taking ASA (20%). It has, however, been shown in earlier publications that ingestion of ASA can cause bleeding not only in the upper GIT, but also in the lower GIT[10,11]. In the present study, we did not specifically investigate the indication for ASA use. However, since chronic ingestion of ASA is usually found in patients with arteriosclerosis, in particular in patients with coronary heart disease[57], cerebral circulatory disorders[58] and peripheral arterial occlusive disease[59], the question must, of course, be considered whether these necroses of the ischemic type might not be due to the underlying disease rather than to the use of ASA. Militating against this possibility, however, is the fact that ischemic colitis in arteriosclerosis[60,61] has other predilection sites, particularly the left colon, in the “borderland area” of the arterial supply between the left colic artery and the inferior mesenteric artery, where the endoscopic picture is of an accumulation of erosions rather than focal erosions and ulcers, and that in these patients, acute perianal bleeding is often found.

Also surprising are the results of our comparative analysis of the four groups of patients (only NSAIDs, only ASA, NSAIDs in combination with ASA, and no known use of NSAID/ASA). Neither the endoscopic nor the histological findings differed among these four groups; this might indicate either that the patients in the no NSAID/ASA group often simply denied using such medication, or that the physicians had not questioned the patients specifically about over-the-counter painkillers.

Our retrospective study should prompt a prospective study. Ideal would be a prospective colonoscopic investigation of patients taking NSAIDs, with consideration being given to the nature and duration as also of the galenic formulation of the preparations employed. Of particular interest would be an investigation of the side effects of COX-1 inhibitors in comparison with COX-2 inhibitors, which also can cause lesions in the lower GIT[21,25]. Only in this way could we obtain data on the incidence, localization and type of lesions as a function of the medication. Such a study in patients with no colon-specific symptoms would, however, hardly be ethically justifiable. Worthy of discussion, however, is the question whether, in patients on NSAIDs, a hemoccult test could be performed and, in the event of positive results, an indication for colonoscopy established. Also, an investigation of the incidence of NSAID-induced lesions in the small intestine employing capsule endoscopy should receive consideration.

What the results of our retrospective study definitely show, however, is that the pathologist who finds focal erosions, ulcers and strictures, together with necroses of the ischemic type in biopsies from the (mainly right) colon, should, more than previously, suggest in his report the possibility of an NSAID-induced mucosal injury. This would then prompt the care-providing physician to look into the patient’s use of NSAIDs, the type of preparation employed, its dosage and galenic formulation, and then possibly replace or discontinue the medication with the aim of clarifying the etiopathogenesis of the lesion and preventing such serious complications such as perforation, chronic bleeding, and strictures. In principle, however, the NSAID/ASA-induced lesions cannot be differentiated histologically from ischemic lesions. This, too, should be emphasized in the histological report. Although arteriosclerosis-induced ischemic colitis is usually located in the left colon, and often manifests as multiple lesions distributed over a large area, other rare causes of ischemic colitis (e.g., vasculitis, distension colitis, emboli) may also give rise to irregularly distributed focal lesions at atypical locations. In our experience as consultant pathologists investigating biopsy and surgical material, the most common endoscopic and histological wrong diagnosis in NSAID-induced colonopathy is Crohn’s disease established on the basis of the discontinuous changes due to NSAID colonopathy. This diagnostic error can, however, be avoided by giving consideration to the age of the patient, since NSAID-induced colonopathy is seen mainly in the elderly people. However, also in the case of young patients with no other clinical and laboratory findings suggestive of Crohn’s disease, the physician should be prompted to enquire about the use of NSAIDs, and if such use is denied, to apply ASA serology to test for possible misuse of painkillers[54].

In conclusion, the present study shows that our retrospective suspected diagnosis of NSAID/ASA-induced lesions based on the histological finding of a focal ischemic necrosis of the colonic mucosa, located mainly in the right colon, is often correct, and may serve to prevent serious complications of NSAID-induced colonopathy. The actual utility of such histological findings and the differential diagnosis vis-a-vis ischemic colitis must, however, be checked in a prospective controlled study.

Science Editor Kumar M and Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Lennert KA, Kootz F. [Nil nocere. Drug-induced small intestinal ulcers]. Munch Med Wochenschr. 1967;109:2058-2062. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Sturges HF, Krone CL. Ulceration and stricture of the jejunum in a patient on long-term indomethacin therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1973;59:162-169. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Huber T, Ruchti C, Halter F. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug-induced colonic strictures: a case report. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1119-1122. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Fellows IW, Clarke JM, Roberts PF. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced jejunal and colonic diaphragm disease: a report of two cases. Gut. 1992;33:1424-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lanas A, Bajador E, Serrano P, Fuentes J, Carreño S, Guardia J, Sanz M, Montoro M, Sáinz R. Nitrovasodilators, low-dose aspirin, other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:834-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 577] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bjarnason I, Hayllar J, MacPherson AJ, Russell AS. Side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the small and large intestine in humans. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1832-1847. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Langman MJ, Morgan L, Worrall A. Use of anti-inflammatory drugs by patients admitted with small or large bowel perforations and haemorrhage. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290:347-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Allison MC, Howatson AG, Torrance CJ, Lee FD, Russell RI. Gastrointestinal damage associated with the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:749-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 718] [Cited by in RCA: 674] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lanas A, Sekar MC, Hirschowitz BI. Objective evidence of aspirin use in both ulcer and nonulcer upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:862-869. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lanas A, Serrano P, Bajador E, Esteva F, Benito R, Sáinz R. Evidence of aspirin use in both upper and lower gastrointestinal perforation. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:683-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wilcox CM, Alexander LN, Cotsonis GA, Clark WS. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs are associated with both upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:990-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Holt S, Rigoglioso V, Sidhu M, Irshad M, Howden CW, Mainero M. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1619-1623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wilson RG, Smith AN, Macintyre IM. Complications of diverticular disease and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a prospective study. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1103-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Campbell K, Steele RJ. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and complicated diverticular disease: a case-control study. Br J Surg. 1991;78:190-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Wing AL, Willett WC. Use of acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a prospective study and the risk of symptomatic diverticular disease in men. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, Shapiro D, Burgos-Vargas R, Davis B, Day R, Ferraz MB, Hawkey CJ, Hochberg MC. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1520-158, 2 p following 1528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2752] [Cited by in RCA: 2534] [Article Influence: 101.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Robert A. An intestinal disease produced experimentally by a prostaglandin deficiency. Gastroenterology. 1975;69:1045-1047. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Whittle BJ. Temporal relationship between cyclooxygenase inhibition, as measured by prostacyclin biosynthesis, and the gastrointestinal damage induced by indomethacin in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:94-98. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Evans SM, Whittle BJ. Interactive roles of superoxide and inducible nitric oxide synthase in rat intestinal injury provoked by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;429:287-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sigthorsson G, Simpson RJ, Walley M, Anthony A, Foster R, Hotz-Behoftsitz C, Palizban A, Pombo J, Watts J, Morham SG. COX-1 and 2, intestinal integrity, and pathogenesis of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1913-1923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | De Vos M, Cuvelier C, Mielants H, Veys E, Barbier F, Elewaut A. Ileocolonoscopy in seronegative spondylarthropathy. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:339-344. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Leirisalo-Repo M, Turunen U, Stenman S, Helenius P, Seppälä K. High frequency of silent inflammatory bowel disease in spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:23-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Smale S, Natt RS, Orchard TR, Russell AS, Bjarnason I. Inflammatory bowel disease and spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2728-2736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Laine L, Connors LG, Reicin A, Hawkey CJ, Burgos-Vargas R, Schnitzer TJ, Yu Q, Bombardier C. Serious lower gastrointestinal clinical events with nonselective NSAID or coxib use. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:288-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Vane JR. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs. Nat New Biol. 1971;231:232-235. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Mahmud T, Rafi SS, Scott DL, Wrigglesworth JM, Bjarnason I. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1998-2003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Brune K, Schweitzer A, Eckert H. Parietal cells of the stomach trap salicylates during absorption. Biochem Pharmacol. 1977;26:1735-1740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lichtenberger LM, Wang ZM, Romero JJ, Ulloa C, Perez JC, Giraud MN, Barreto JC. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) associate with zwitterionic phospholipids: insight into the mechanism and reversal of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal injury. Nat Med. 1995;1:154-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Giraud MN, Motta C, Romero JJ, Bommelaer G, Lichtenberger LM. Interaction of indomethacin and naproxen with gastric surface-active phospholipids: a possible mechanism for the gastric toxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:247-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rampton DS. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the lower gastrointestinal tract. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;22:1-4. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pihan G, Rogers C, Szabo S. Vascular injury in acute gastric mucosal damage. Mediatory role of leukotrienes. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:625-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Davies NM. Toxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the large intestine. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:1311-1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wallace JL, Arfors KE, McKnight GW. A monoclonal antibody against the CD18 leukocyte adhesion molecule prevents indomethacin-induced gastric damage in the rabbit. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:878-883. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Davies NM, Wallace JL. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal toxicity: new insights into an old problem. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:127-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Appleyard CB, McCafferty DM, Tigley AW, Swain MG, Wallace JL. Tumor necrosis factor mediation of NSAID-induced gastric damage: role of leukocyte adherence. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:G42-G48. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Rothlein R, Czajkowski M, Kishimoto TK. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in the inflammatory response. Chem Immunol. 1991;50:135-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Whittle BJ. New dogmas or old? Gut. 2003;52:1379-1381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Bjarnason I, Takeuchi K, Simpson R. NSAIDs: the emperor's new dogma? Gut. 2003;52:1376-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Aabakken L, Osnes M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced disease in the distal ileum and large bowel. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;163:48-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gargot D, Chaussade S, d'Alteroche L, Desbazeille F, Grandjouan S, Louvel A, Douvin J, Causse X, Festin D, Chapuis Y. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced colonic strictures: two cases and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2035-2038. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Gut A, Halter F, Ruchti C. [Nonsteroidal antirheumatic drugs and acetylsalicylic acid: adverse effects distal to the duodenum]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1996;126:616-625. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Bjarnason I, Hayllar J, MacPherson AJ, Russell AS. Side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the small and large intestine in humans. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1832-1847. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Gibson GR, Whitacre EB, Ricotti CA. Colitis induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Report of four cases and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:625-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Sacanella E, Muñoz F, Cardellach F, Estruch R, Miró O, Urbano-Márquez A. Massive haemorrhage due to colitis secondary to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72:57-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Sukumar L. Recurrent small bowel obstruction associated with piroxicam. Br J Surg. 1987;74:186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Bjarnason I, Price AB, Zanelli G, Smethurst P, Burke M, Gumpel JM, Levi AJ. Clinicopathological features of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug-induced small intestinal strictures. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1070-1074. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Lang J, Price AB, Levi AJ, Burke M, Gumpel JM, Bjarnason I. Diaphragm disease: pathology of disease of the small intestine induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:516-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Levi S, de Lacey G, Price AB, Gumpel MJ, Levi AJ, Bjarnason I. "Diaphragm-like" strictures of the small bowel in patients treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Br J Radiol. 1990;63:186-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Withcomb DC, Martin SP, Trellis AR, Evans BA, Becich MJ. "Diaphragmlike" stricture and ulcer of the colon during diclofenac treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:2341-2343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Halter F, Weber B, Huber T, Eigenmann F, Frey MP, Ruchti C. Diaphragm disease of the ascending colon. Association with sustained-release diclofenac. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;16:74-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Anthony A, Dhillon AP, Sim R, Nygard G, Pounder RE, Wakefield AJ. Ulceration, fibrosis and diaphragm-like lesions in the caecum of rats treated with indomethacin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:417-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Robinson MH, Wheatley T, Leach IH. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug-induced colonic stricture. An unusual cause of large bowel obstruction and perforation. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:315-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Klee M, Vogel CU, Diehl HG, Stolte M. Das Diaphragma-Kolon - Eine schwerwiegende Nebenwirkung nichtsteroidaler Antirheumatika (NSAR). Leber Magen Darm. 1998;28:137-141. |

| 55. | Stolte M, Panayiotou S, Schmitz J. Can NSAID/ASA-induced erosions of the gastric mucosa be identified at histology? Pathol Res Pract. 1999;195:137-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Vieth M, Müller H, Stolte M. Can the diagnosis of NSAID-induced or Hp-associated gastric ulceration be predicted from histology? Z Gastroenterol. 2002;40:783-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Risk of myocardial infarction and death during treatment with low dose aspirin and intravenous heparin in men with unstable coronary artery disease. The RISC Group. Lancet. 1990;336:827-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 718] [Cited by in RCA: 597] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Swedish Aspirin Low-Dose Trial (SALT) of 75 mg aspirin as secondary prophylaxis after cerebrovascular ischaemic events. The SALT Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1991;338:1345-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 500] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 59. | Patrono C. Aspirin as an antiplatelet drug. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1287-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 682] [Cited by in RCA: 610] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Newman JR, Cooper MA. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding and ischemic colitis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2002;16:597-600. [PubMed] |

| 61. | MacDonald PH. Ischaemic colitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:51-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Singh G, Ramey DR. NSAID induced gastrointestinal complications: the ARAMIS perspective -1997. Arthritis, Rheumatism, and Aging Medical Information System. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:8-16. |