Published online Sep 14, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i34.5303

Revised: March 3, 2005

Accepted: March 9, 2005

Published online: September 14, 2005

AIM: To focus on the role of CD40 and CD40L in their pathogenesis.

METHODS: We analyzed by immunohistochemistry the CD40 and CD40L expression in the pouch mucosa of 28 patients who had undergone RPC for UC, in the terminal ileum of 6 patients with UC and 11 healthy subjects. We also examined by flow cytometry the expression of CD40 by B lymphocytes and monocytes in the peripheral blood of 20 pouch patients, 15 UC patients and 11 healthy controls.

RESULTS: Ileal pouch mucosa leukocytes presented a significantly higher expression of CD40 and CD40L as compared to controls. This alteration correlated with pouchitis, but was also present in the healthy pouch and in the terminal ileum of UC patients. CD40 expression of peripheral B lymphocytes was significantly higher in patients with UC and pouch, respect to controls. Increased CD40 levels in blood B cells of pouch patients correlated with the presence of spondyloarthropathy, but not with pouchitis, or inflammatory indices.

CONCLUSION: High CD40 expression in the ileal pouch mucosa could be implied in the pathogenesis of pouchitis following proctocolectomy for UC, whereas its increased levels on peripheral blood B lymphocytes are associated with the presence of extraintestinal manifestations.

- Citation: Polese L, Angriman I, Franchis GD, Cecchetto A, Sturniolo GC, D’Incà R, Scarpa M, Ruffolo C, Norberto L, Frego M, D’Amico DF. Persistence of high CD40 and CD40L expression after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(34): 5303-5308

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i34/5303.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i34.5303

The etiology of ulcerative colitis (UC) is not clear, but abnormal immunological activity against normally tolerated antigens has been demonstrated[1,2]. This disease is usually treated by immunosuppressive or anti-inflammatory drugs, but, in the case of unresponsive or steroid-dependent patients, or dysplasia, surgical treatment is indicated.

The standard of care for elective surgical treatment of patients with UC is restorative proctocolectomy (RPC), with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA). After RPC, over 90% patients have shown good long-term function and high satisfaction, with full continence at 5 years in 72% of subjects and a mean stool frequency of six bowel movements per day[3,4]. The health-related quality of life reported by these patients is similar to that in subjects with UC in remission and better than in patients with moderate-severe colitis[5]. However, these patients sometimes suffer from pouchitis and extraintestinal manifestations such as arthritis, uveitis, erythema nodosum or pyoderma gangrenosum.

Pouchitis, an inflammation of the ileal reservoir, can develop in up to 50% of the patients that undergo RPC for UC, but in less than 1% of those operated on RPC for familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)[6-8]. Clinically it is characterized by bloody diarrhea, fever, abdominal cramps and urgent defecation, and, at times, the symptoms resemble those of UC. Fortunately excision of the pouch is required in only 1-2% of these patients in whom the disease becomes chronic[9,10]. Several different hypotheses have been made to explain the etiology of pouchitis, which might be caused by ischemia of the ileal reservoir, transformation of the microbial flora, or fecal stasis possibly causing bacterial overgrowth or by a recurrence of UC. The last postulation has been sustained by many studies demonstrating immunological aspects that are similar to those in UC. A comparable expression to what is seen in UC of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL6, IL8 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α in the gut[11], an increased concentration of IgG and the activation of CD4 T cells[12,13] are all patterns demonstrating immunologic over-activity.

CD40 and CD154 (CD40 ligand or CD40L), two surface molecules, both members of TNF receptor family, are co-stimulators, expressed respectively by the antigen presenting cell and the T cells. While their presence is necessary to activate the immune response toward the antigen during its presentation, their absence leads to tolerance[14]. It has been reported that the expression of CD40 and CD40L by gut leukocytes is elevated in patients with UC and Crohn’s disease even during remission, as compared to healthy controls or to other inflammatory events[15-17]. Sawada-Hase et al[18] also found an increased expression of CD40 by the blood B cells of patients with active UC and by the blood monocytes of patients with active Crohn’s disease. Recent studies on inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) have demonstrated that CD40/CD40L interaction plays a key role not only in setting off an immune reaction, but also in the late inflammatory stage. In fact, there is evidence that CD40L positive T cells can induce cell adhesion molecules and expression of soluble mediators by CD40-positive human intestinal fibroblasts and microvascular endothelial cells. This event recruits more T cells from the blood to the tissue, thus amplifying intestinal inflammation[19].

The aim of this study was to evaluate if CD40 and CD40L may have a role in the pathogenesis of pouchitis. It was with this interest that we analyzed CD40 and CD40L expression by leukocytes from the ileal pouch mucosa and from the blood of patients who underwent RPC for UC, comparing it to that in non-operated UC patients and normal controls. The correlation between elevated levels of these molecules and the presence of pouchitis or extra-intestinal manifestations was also evaluated.

Patients In the first part of the study, histologic samples were obtained from the ileal pouch biopsies of 28 patients (16 males, 12 females) who had undergone RPC for UC. Patients’ mean age was 36 years (range 22-52 years) and time interval after RPC was in mean 5 ± 4 years. According to the pouchitis disease activity index (PDAI) classification[20], 14 of these patients presented pouchitis (score ≥ 7), while the other 14 presented a healthy pouch (score < 7). A total of 76 pouch biopsies (35 from pouchitis and 41 from healthy pouches) were analyzed. Histochemical analyses were also carried out on ileal biopsies taken during standard surveillance colonoscopy of 6 consecutive un-operated patients with UC without ileitis and of 11 healthy subjects (who underwent endoscopy for screening, and whose test result was normal).

Methods All the samples were kept in formalin and subsequently paraffin embedded. The expression of CD40 (clone MAB 89, mouse, Immunotech) and CD154 (clone H-125, rabbit, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) were analyzed in the same sample by immunohistochemical staining. Staining was performed using avidin-biotin complex (ABC), as described elsewhere[15].

In order to quantify the number of CD40+ and CD154+ cells present, we counted the percentage of leukocytes stained by the ABC immediately below the epithelium. We examined 10 fields at ×60 magnification from each sample. The percentage of the molecular expression was determined in a “blind” way by a single pathologist, who did not know the sample’s origin.

Patients In the second part of the study, we collected blood for flow cytometric analysis from 20 patients (12 males and 8 females, mean age 47 years, range 31-70 years) who had undergone RPC for UC (10 of them also participated in the first part of the study performed with immunohistochemistry), 15 patients with UC (7 males, 8 females, mean age 47 years, range 23-59 years) and 11 healthy subjects (controls). Patients receiving immunosuppressive or steroid treatment were excluded. Of the 20 patients who had undergone IPAA, 7 presented diagnosis of pouchitis, according to the PDAI (score ≥ 7) and 13 did not (score < 7). Extraintestinal diseases were found in 7 (6 with spondyloarthropathy, 1 pyoderma gangrenosum), while 13 were asymptomatic. Presence of both pouchitis and extraintestinal manifestations was found in 3. The diagnosis of spondyloarthropathy was made according to the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group criteria[21]. Of the 15 patients with UC, 10 were in remission, 5 were in activity according to clinical and endoscopic patterns[22,23]. Extraintestinal symptoms were reported in five patients (three with spondyloarthropathy, one uveitis, one arthritis and pyoderma gangrenosum).

ESR and CRP were also measured respectively by Westergren method and immunonephelometry. We considered 6 mg/L and 15 mm/h the cut-off points for CRP and ESR, respectively.

All sampling procedures for histology and flow cytometry were performed after informed consent was obtained from each patient. Methods Blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes. A four flow cytometric analysis was performed, with the sequent associations:

- CD45, CD40, CD20, CD14

- CD45, CD3, CD154

Anti-CD20 and anti-CD45 mAb were obtained from Coulter Beckman (Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA), anti-CD14 mAb, anti-CD40 mAb and anti-CD154 (CD40L) from Becton Dickinson & Co., (San Jose, CA) (Table 1). Anti CD-3 mAb was obtained from Caltag Laboratories (Bayshore Burlingame, CA, USA) (Table 1). For flow cytometry, all mAbs were used at optimal saturating concentrations as recommended by the manufacturers.

| Cluster differentiation | Clone | Isotype | Fluorochromes | Excitation | Emission | Source |

| CD45 | J.33 | IgG1 | ECD | 486-575 | 610-635 | Coulter |

| CD20 | H299 (B1) | IgG2a | FITC | 468-505 | 504-541 | Coulter |

| CD14 | M5E2 | IgG2a | PE | 486-575 | 568-590 | Becton-Dickinson |

| CD40 | 5C3 | IgG1 | PC5 | 486-580 | 660-680 | Becton-Dickinson |

| CD154 | TRAP1 | IgG1 | PC5 | 486-580 | 660-680 | Becton-Dickinson |

| CD3 | UCHT1 | IgG1 | FITC | 468-505 | 504-541 | Caltag |

Quadruple staining was performed for CD20 (FITC), CD45 (ECD), CD14 (PE), CD40 (PC5) on one hand and triple staining for CD45 (ECD), CD154 (PC5), CD3 (FITC) on the other hand. As for the quadruple staining the cells were washed in FACS buffer containing PBS, 5% FCS, 0.05% sodium azide and incubated with 10 mg of human IgG (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for 30 min at 4-8°C to block Fc receptors. Cells were washed to remove excess IgG and were quadruple-stained with either PC5-conjugated mAb against human CD40 or PC5-control IgG1 mAb, PE-conjugated mAb against CD14, or PE-control IgG mAb, FITC-conjugated mAb against CD20 or FITC-control IgG mAb and ECD-conjugated mAb against CD45 for 30 min at 4-8°C. Cells were washed twice, re-suspended in FACS buffer, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry using Coulter EPICS XL-MCL (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA). PBMCs were gated according to their CD45 expression characteristics. Different subsets of cells (CD20, CD14) were gated further based on FL1 and FL2 staining. A similar procedure was utilized for the co-staining of CD154, CD45, and CD3. An immunologic gate on CD20+ and CD14+ cells to evidence CD40 and on CD3+ to reveal CD154+ were respectively performed. As CD40 is expressed by most of the peripheral blood-except terminally differentiated-B cells, but the number of molecules on the lymphocytes surface rises during UC activity[18], we arbitrarily regulated the FL3 photomultiplicator voltage, positioning the CD40 expression below the threshold, previously set by the negative isotypic control of the relative antibody. In this way, all the B cells with homogeneous CD40 expression were below, while those with high CD40 expression were above the cut-off. In the present manuscript, we have called these cells as “high fluorescence intensity (hfi) CD40+”. This instrumental setting was performed utilizing blood samples from four healthy controls (not included in the study). After that, isotypic controls were used for all the samples, maintaining the voltage setting of the photomultiplicator at the new level. We considered the CD40 expression by B lymphocytes above the cut-off level a pattern of activated B cells[18]. The same methods were utilized to detect monocytes CD14+ with high CD40 expression.

The aim was to detect a 50% difference, since a 300% difference was found in previous studies on CD40 tissue and blood expression in UC patients with respect to controls[15,18]. So the minimum sample sizes were calculated at one-sided alpha of 5%, a power of 80% and an estimated standardized effect size of 100%.

Results are expressed as mean±SE. Statistical analysis was performed by multi-way ANOVA followed by least significant difference (LSD) test. When only two samples were compared, Mann-Whitney U test was utilized. Frequency analysis was performed with Fisher exact test. Correlations were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

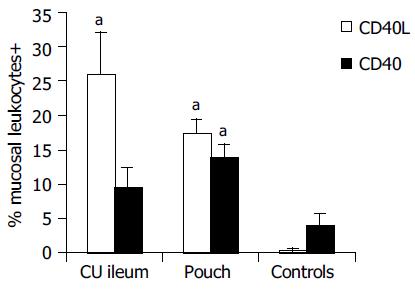

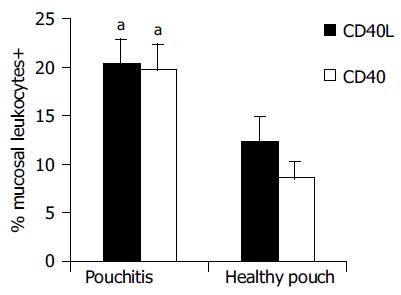

Results of immunohistochemical analysis are presented in Table 2. In healthy controls, the percentage of leukocytes exposing CD40 on the cell surface in the ileal mucosa was 4.0 ± 1.62%. They were located just below the epithelium, probably in response to stimuli of luminal origin, as previously found in the normal colon[15]. Higher CD40 expression was found in the ileal pouch mucosa (14.0 ± 1.72%, P < 0.05) and in the ileal mucosa of non-operated UC patients (9.60 ± 2.73%, in this case, although Mann-Whitney U test gave a statistical significant difference (P < 0.05), the comparison with healthy controls did not reach the full statistical significance with LSD test). In the mucosa of the ileal pouch, there were more CD40+ cells in patients with active pouchitis compared to subjects with a healthy pouch (19.7 ± 2.75% vs 8.6 ± 1.76%, P < 0.01) and their percentage correlated with the PDAI score (P < 0.01). Similarly, we found more CD40L+ cells in the ileal mucosa of the pouch (17.5 ± 2%), rather than in healthy controls, in whom the expression of this molecule was hardly detectable (0.4 ± 0.21%, P < 0.01, Figure 1). CD40L+ cells percentage (26.0 ± 6.12%, P < 0.01) in the ileal mucosa of non-operated patients with UC was also high. During an episode of pouchitis, CD40L -just as CD40-expression was increased (20.4 ± 2.54% vs 12.3 ± 2.64%, P = 0.01, Figure 2) and correlated with the PDAI score (P < 0.01). The ileal tissue of healthy pouches had significantly more CD40L than negative controls (P < 0.01). CD40 and CD40L expression was not influenced by the pouch age.

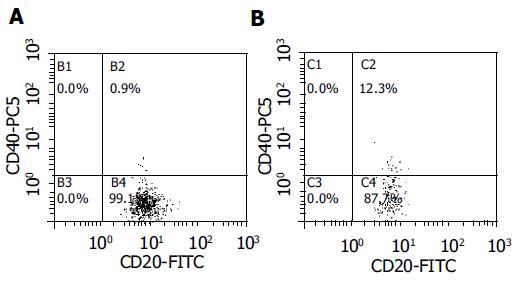

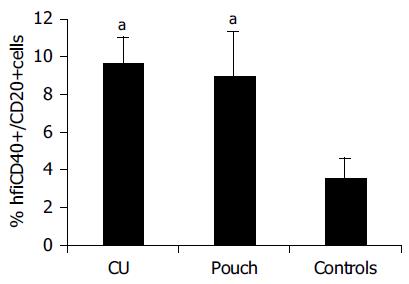

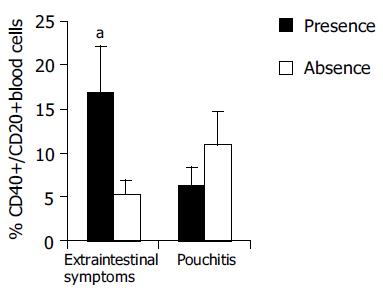

Results of flow cytometric analysis are presented in Table 3 There was a less homogeneous distribution of blood CD40+B cells in the flow cytometry diagram in samples presenting elevated CD40 expression, with respect to that in normal controls (Figure 3). Blood B cells of pouch and UC patients presented higher CD40 expression compared to controls (hfiCD40+/CD20+ cells percentage respectively 9.0 ± 2.37% in patients with pouches, 9.7 ± 1.34% in those with UC and 3.6 ± 0.99% in controls, P < 0.05, Figure 4). All except 1 control presented a percentage of hfiCD40+/CD20+ blood cells < 7% (10/11, 91%), while 11/15 (73%) UC patients and 10/20 (50%) pouch patients presented a percentage ≥7%. No significant increase in CD40 expression by CD14+ blood population (monocytes) was found in UC (0.38 ± 0.13%) or pouch (0.16 ± 0.06%) with respect to controls (0.09 ± 0.06%). It was found that CD40L was not expressed in the CD3 population of the subjects analyzed.

| HfiCD40+CD20+ (%) | P | HfiCD40+CD14+ (%) | P | |

| UC vs controls | 9.7 ± 1.34 vs 3.6 ± 0.99 | < 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.13 vs 0.09 ± 0.06 | NS |

| Pouch vs controls | 9.0 ± 2.37 vs 3.6 ± 0.99 | < 0.05 | 0.16 ± 0.06 vs 0.09 ± 0.06 | NS |

| Extraint+ vs extraint- | 16.86 ± 5.25 vs 5.30 ± 1.58 | < 0.05 | 0.1 ± 0.03 vs 0.2 ± 0.13 | NS |

| PDAI ≥ 7 vs PDAI < 7 | 11.00 ± 3.6 vs 6.40 ± 2.0 | NS | 0.1 ± 0.04 vs 0.2 ± 0.08 | NS |

| CRP+ vs CRP– | 8.6 ± 2.25 vs 10.7 ± 2.0 | NS | 0.2 ± 0.13 vs 0.7 ± 0.4 | NS |

| ESR+ vs ESR– | 8.6 ± 1.8 vs 10.4 ± 2.8 | NS | 0.3 ± 0.2 vs 0.7 ± 0.4 | NS |

No significant difference in CD40 expression by B cells was found between normal (hfiCD40+/CD20+ 11.00 ± 3.6%) and inflamed pouches (6.40 ± 2%). Moreover, no correlation was found with PDAI score or with pouch age. Enhanced CD40 expression in B lymphocytes of pouch population, instead, was correlated with extra-intestinal manifestations. Patients with extraintestinal manifestations (spondyloarthropathy, or pyoderma gangrenosum) showed a significant increase of CD40 expression (hfiCD40+CD20+ 16.86 ± 5.25% vs 5.30 ± 1.58% in patients without extraintestinal manifestations, P < 0.05). The difference was statistically significant also considering only patients with spondyloarthropathy (Figure 5). The CD40 expression in blood monocytes was not correlated to extraintestinal manifestations. Patients with pouchitis did not present a higher incidence of extraintestinal manifestations.

CD40 expression in B lymphocytes or in monocytes did not correlate with the levels of ESR or CRP.

The pathogenesis of pouchitis after proctocolectomy remains to be elucidated. From our results, pouchitis does not seem to represent the manifestation of systemic disease. In fact we found activated peripheral B cells in the presence of arthritis, but not in the presence of pouchitis. Moreover, pouchitis was not related to extraintestinal manifestations. Our results are in disagreement with those reported by Lohmuller et al[24] and Hata et al[25] which found higher rates of pouchitis in patients with extraintestinal manifestations than in those without. Our findings were supported instead by Thomas et al[26] who observed that histological scores of pouch inflammation were not different in patients with and without joints diseases.

Increased CD40 and CD40L expression was found in the terminal ileum of some patients with UC who had not undergone surgery. This finding is in agreement with the hypothesis that the ileal segment used for pouch construction, even if apparently regular, could nevertheless be abnormal with regard to its immunology and function[27]. Known underlying diseases in the terminal ileum could be Crohn’s disease, indeterminate colitis, or backwash ileitis[6]. In a study by Battaglia et al[17] the ileal tissue of patients with Crohn’s disease presented higher levels of CD40L and CD40 on T and B lymphocytes, with respect to controls. Backwash ileitis has already been considered as a risk factor for pouchitis. Schmidt et al[28] analyzed 67 preoperative terminal ileal and colonic resections in patients with UC who underwent proctocolectomy. In their study ileal inflammation or pancolitis were significant predictors of subsequent pouch inflammation. On the other hand, Gustavsson et al[29] found a similar incidence of pouchitis in patients presenting backwash ileitis at surgery than in those without. The alteration we found in CD40 and CD40L expression in the terminal ileum of patients with UC is not associated with clear inflammatory patterns. Nevertheless it could yield a reduced tolerance status that becomes clinically evident only in certain conditions, such as, probably, the presence of fecal stasis, different bacterial flora or colonic metaplasia. Colonic metaplasia alone cannot cause pouchitis, since this histologic pattern has been found in 50% of pouch constructed for patients with FAP, which rarely becomes inflamed[30].

The analysis of CD40 and CD40L in the ileum of patients with UC who are possible candidates for RPC could represent a predictive marker for the future development of pouchitis or fistulas. Prospective studies are needed to clarify this hypothesis.

The analysis of soluble CD40L in the serum using ELISA could be easier than the research by flow cytometry of CD40 and CD40L on B lymphocytes’ and monocytes’ surface, but it was excluded from this study because it was mainly expressed by platelets[31]. The presence of increased CD40 expression in blood B lymphocytes of IBD patients has already been reported by others. Sawada-Hase et al[18] found a higher CD40 expression in the CD19+ blood cells in patients with active UC and in the CD14+ blood cells in subjects with active Crohn’s disease. CD40 expression in peripheral B cells has however never been analyzed in pouch patients. An increased CD40 expression in the blood B lymphocytes of subjects who have undergone RPC demonstrates that some systemic alterations persist following the surgical treatment of UC, suggesting that it is a systemic rather than just a colonic disease. Nevertheless, only half of the pouch patients presented an altered expression of this molecule on peripheral B-cells’ surface. Extraintestinal manifestations of UC-such as spondyloarthropathy-seem to be related to CD40 levels on blood B cells, while other analyzed factors, like pouchitis, pouch age, ESR or CRP, do not.

The importance of CD40 and CD40L in arthritis has been previously demonstrated. In patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), in fact, increased expression of CD40 on synovial monocytes, fibroblasts and dendritic cells has been reported and blocking CD40-CD154 interaction improved collagen-induced arthritis in a murine model of RA[35]. Thomas et al[26] studied 97 UC patients with pouch for rheumatological diseases. Articular symptoms in joints were reported in 31% of the patients, but clinical and radiological findings were nearly normal. On the basis of our findings, increased CD40 expression by blood B cells seems to be a measurable marker of this disease.

In conclusion, pouchitis is characterized by an increased expression of CD40 and CD40L on mucosal leukocytes. This result, also found in the terminal ileum of some UC patients who were analyzed here, could represent a predisposing factor for pouchitis, activated in the presence of bacteria and feces following pouch construction or colonic metaplasia.

High levels of CD40 on the surface of blood B cells did not correlate with pouchitis, but with spondyloarthropathy. These findings suggest a different pathogenesis of the two diseases, with local events the first, systemic immunological alterations the second. Prospective studies, before and after pouch construction and before and after symptoms, are mandatory to evaluate these analyses as prognostic markers for the development of pouchitis, if conducted in the ileal mucosa, and of spondyloarthropathy following RPC, if performed on blood samples.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Radford-Smith G. Ulcerative colitis: an immunological disease? Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;11:35-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:182-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1493] [Cited by in RCA: 1484] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lavery IC, Sirimarco MT, Ziv Y, Fazio VW. Anal canal inflammation after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. The need for treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:803-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Michelassi F, Lee J, Rubin M, Fichera A, Kasza K, Karrison T, Hurst RD. Long-term functional results after ileal pouch anal restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: a prospective observational study. Ann Surg. 2003;238:433-441; discussion 442-445. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Scarpa M, Angriman I, Ruffolo C, Ferronato A, Polese L, Barollo M, Martin A, Sturniolo GC, D'Amico DF. Health-related quality of life after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: long-term results. World J Surg. 2004;28:124-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nicholls RJ, Banerjee AK. Pouchitis: risk factors, etiology, and treatment. World J Surg. 1998;22:347-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stocchi L, Pemberton JH. Pouch and pouchitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30:223-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Simchuk EJ, Thirlby RC. Risk factors and true incidence of pouchitis in patients after ileal pouch-anal anastomoses. World J Surg. 2000;24:851-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ståhlberg D, Gullberg K, Liljeqvist L, Hellers G, Löfberg R. Pouchitis following pelvic pouch operation for ulcerative colitis. Incidence, cumulative risk, and risk factors. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1012-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gramlich T, Delaney CP, Lynch AC, Remzi FH, Fazio VW. Pathological subgroups may predict complications but not late failure after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for indeterminate colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:315-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Patel RT, Bain I, Youngs D, Keighley MR. Cytokine production in pouchitis is similar to that in ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:831-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stallmach A, Schäfer F, Hoffmann S, Weber S, Müller-Molaian I, Schneider T, Köhne G, Ecker KW, Feifel G, Zeitz M. Increased state of activation of CD4 positive T cells and elevated interferon gamma production in pouchitis. Gut. 1998;43:499-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Stallmach A, van Look M, Scheiffele F, Ecker KW, Feifel G, Duchmann R, Zeitz M. IgG, albumin, and sCD44 in whole-gut lavage fluid are useful clinical markers for assessing the presence and activity of pouchitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1999;14:35-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | van Kooten C, Banchereau J. Functional role of CD40 and its ligand. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1997;113:393-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Polese L, Angriman I, Cecchetto A, Norberto L, Scarpa M, Ruffolo C, Barollo M, Sommariva A, D'Amico DF. The role of CD40 in ulcerative colitis: histochemical analysis and clinical correlation. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:237-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liu Z, Colpaert S, D'Haens GR, Kasran A, de Boer M, Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Ceuppens JL. Hyperexpression of CD40 ligand (CD154) in inflammatory bowel disease and its contribution to pathogenic cytokine production. J Immunol. 1999;163:4049-4057. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Battaglia E, Biancone L, Resegotti A, Emanuelli G, Fronda GR, Camussi G. Expression of CD40 and its ligand, CD40L, in intestinal lesions of Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3279-3284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sawada-Hase N, Kiyohara T, Miyagawa J, Ueyama H, Nishibayashi H, Murayama Y, Kashihara T, Nakahara M, Miyazaki Y, Kanayama S. An increased number of CD40-high monocytes in patients with Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1516-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vogel JD, West GA, Danese S, De La Motte C, Phillips MH, Strong SA, Willis J, Fiocchi C. CD40-mediated immune-nonimmune cell interactions induce mucosal fibroblast chemokines leading to T-cell transmigration. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:63-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Batts KP, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a Pouchitis Disease Activity Index. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:409-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 550] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dougados M, van der Linden S, Juhlin R, Huitfeldt B, Amor B, Calin A, Cats A, Dijkmans B, Olivieri I, Pasero G. The European Spondylarthropathy Study Group preliminary criteria for the classification of spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1218-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1551] [Cited by in RCA: 1500] [Article Influence: 44.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Seo M, Okada M, Yao T, Ueki M, Arima S, Okumura M. An index of disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:971-976. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Baron JH, Connell AM, Lennard-jones je. variation between observers in describing mucosal appearances in proctocolitis. Br Med J. 1964;1:89-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 441] [Cited by in RCA: 458] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lohmuller JL, Pemberton JH, Dozois RR, Ilstrup D, van Heerden J. Pouchitis and extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Ann Surg. 1990;211:622-627; discussion 622-627;. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Hata K, Watanabe T, Shinozaki M, Nagawa H. Patients with extraintestinal manifestations have a higher risk of developing pouchitis in ulcerative colitis: multivariate analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1055-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Thomas PD, Keat AC, Forbes A, Ciclitira PJ, Nicholls RJ. Extraintestinal manifestations of ulcerative colitis following restorative proctocolectomy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1001-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kühbacher T, Schreiber S, Runkel N. Pouchitis: pathophysiology and treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1998;13:196-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Schmidt CM, Lazenby AJ, Hendrickson RJ, Sitzmann JV. Preoperative terminal ileal and colonic resection histopathology predicts risk of pouchitis in patients after ileoanal pull-through procedure. Ann Surg. 1998;227:654-662; discussion 663-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gustavsson S, Weiland LH, Kelly KA. Relationship of backwash ileitis to ileal pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:25-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Polese L, Keighley MR. Adenomas at resection margins do not influence the long-term development of pouch polyps after restorative proctocolectomy for familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Surg. 2003;186:32-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Danese S, Katz JA, Saibeni S, Papa A, Gasbarrini A, Vecchi M, Fiocchi C. Activated platelets are the source of elevated levels of soluble CD40 ligand in the circulation of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gut. 2003;52:1435-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Thomas R, Davis LS, Lipsky PE. Rheumatoid synovium is enriched in mature antigen-presenting dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1994;152:2613-2623. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Rissoan MC, Van Kooten C, Chomarat P, Galibert L, Durand I, Thivolet-Bejui F, Miossec P, Banchereau J. The functional CD40 antigen of fibroblasts may contribute to the proliferation of rheumatoid synovium. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;106:481-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sekine C, Yagita H, Miyasaka N, Okumura K. Expression and function of CD40 in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:1048-1053. [PubMed] |