Published online Aug 14, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i30.4674

Revised: October 3, 2004

Accepted: October 8, 2004

Published online: August 14, 2005

AIM: Oligomeric proanthocyanidins (OPC), natural polyphenolic compounds found in plants, are known to have antioxidant and anti-cancer effects. We investigated whether the anti-cancer effects of the OPC are induced by apoptosis on human colorectal cancer cell line, SNU-C4.

METHODS: Colorectal cancer cell line, SNU-C4 was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The cytotoxic effect of OPC was assessed by 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenylt-etrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. To find out the apoptotic cell death, 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and caspase-3 enzyme assay were performed.

RESULTS: In this study, cytotoxic effect of OPC on SNU-C4 cells appeared in a dose-dependent manner. OPC treatment (100 µg/mL) revealed typical morphological apoptotic features. Additionally OPC treatment (100 µg/mL) increased level of BAX and CASPASE-3, and decreased level of BCL-2 mRNA expression. Caspase-3 enzyme activity was also significantly increased by treatment of OPC (100 µg/mL) compared with control.

CONCLUSION: These data indicate that OPC caused cell death by apoptosis through caspase pathways on human colorectal cancer cell line, SNU-C4.

- Citation: Kim YJ, Park HJ, Yoon SH, Kim MJ, Leem KH, Chung JH, Kim HK. Anticancer effects of oligomeric proanthocyanidins on human colorectal cancer cell line, SNU-C4. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(30): 4674-4678

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i30/4674.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i30.4674

Oligomeric proanthocyanidins are some of the most abundant polyphenolic substances in the plant kingdom. Proanthocyanidins are an integral part of the human diet, found in high concentration in fruits, vegetables and seeds as well as in most types of tea and red wine[1]. Numerous studies have reported that flavonoids have potent antioxidant effects through scavenging of superoxide and hydroxyl radicals[2] and anti-proliferative actions via inhibition of metabolic pathways and inhibition of intra-cellular signal transduction[3]. In addition, a variety of proanthocyanidins have been shown to be anti-bacterial, anti-viral[4], anti-carcinogenic[3-6], anti-inflammatory[7,8], anti-allergic[9-11] and consequently reduce the concentration of reactive oxygen species[12] and low density lipoprotein oxidation[13], and cardioprotective effects in human beings[14].

Despite their beneficial effects, the great extent of polyphenolics are not absorbed and metabolized easily due to their chemical structures and the glycosylation, acylation, conjugation, polymerization and the solubility of the compound. Monomeric flavonoids are absorbed in the small intestine. However, polymeric polyphenolics may be degraded by intestinal and colonic microflora, and then excreted in the feces, and the monomers appear to be absorbed in a dose-dependent manner[15].

Apoptosis, a programmed cell death, also plays an essential role as a protective mechanism against cancer cells[16]. Induction of apoptosis is a highly desirable mode as a therapeutic strategy for cancer control. In fact, many chemopreventive agents act through the induction of apoptosis as a mechanism to suppress carcinogenesis[17]. Recently, cancer chemotherapy has gradually improved with the development and discovery of novel anti-tumor drugs, but sometimes these drugs have been limited in clinical application by drug resistance of tumor and by serious damage to the normal tissues and cells.

Oligomeric proanthocyanidins incubated with several human cancer cell lines (breast, lung, gastric, and skin) revealed a selective cytotoxicity for the cancerous cells. However OPC has not been tested for colorectal cancer which is one of the major cause of cancer-related mortality in the West.

In this study, we examined the inhibitory effects of OPC on cancer cell proliferation, and pharmacological mechanism for anti-tumor effects on human colorectal cancer cell line SNU-C4.

Grape seed OPC was donated by Doosan Biotech (Yongin, Korea). According to the manufacturer, this OPC extract contained essentially, dimeric (17.4%), trimeric (16.3%), tetrameric (13.3%) and oligomeric (5-13 Units) (53.0%) proanthocyanidins. DAPI and caspase-3 assay kit were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). MTT and TUNEL assay kits were purchased from Roche (Roche, Basal, Switzerland).

The SNU-C4 cell line was obtained from Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB, Seoul, Korea). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco). Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2-95% O2 air at 37°C, and the medium was changed every 2 d.

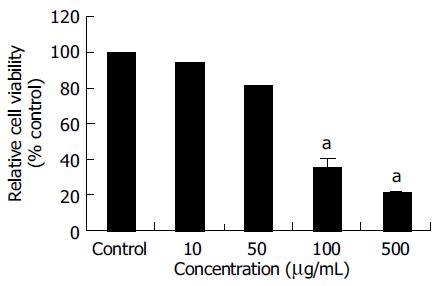

Cell viability was determined using the MTT assay kit according to a previously described protocol[18]. In order to detect the cytotoxicity of OPC, SNU-C4 cells were treated with OPC at the concentrations of 10, 50, 100, and 500 µg/mL for 24 h. The control group was treated with the same amount of vehicle. After the MTT, labeling reagent (5 mg/mL) was added to each group and incubated for 4 h at 37°C, they were incubated for 12 h with the solubilization solution in which the formazan crystals formed by MTT will be dissolved. The absorbance was measured with a microtiter plate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT, USA) at a test wavelength of 595 nm with a reference wavelength of 690 nm. The optical density (A) was calculated as the difference between the reference wavelength and the test wavelength. Percent viability was calculated as (A of drug-treated sample/A of none-treated control) ×100.

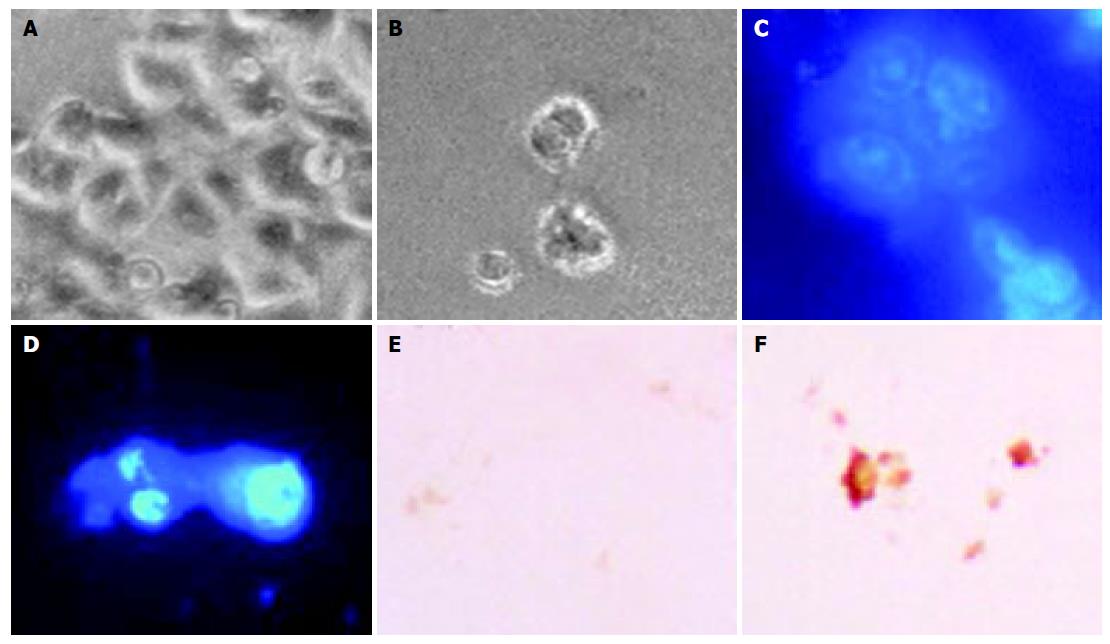

The nucleic condensation of apoptosis was determined by DAPI staining. SNU-C4 cells treated with OPC (100 µg/mL) for 24 h were cultured on four-chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY, USA). The cells were fixed in 40 g/L paraformaldehyde for 30 min, and were incubated for 30 min in the dark, including 1 µg/mL DAPI solution. They were observed through a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Oberköchen, Germany).

For detection of apoptotic cells, TUNEL assay was performed by ApoTag® peroxidase in situ cell death detection kit (Roche, Basal, Switzerland). After 24 h exposure to OPC (100 µg/mL), cultured SNU-C4 cells were fixed in acetic acid at -20°C for 5 min. Incubated with digoxigenin-conjugated dUTP in a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-catalyzed reaction for 1 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere. The fixed cells were immersed in stop/wash buffer for 10 min at room temperature, and the cells were again incubated with an anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugating peroxidase for 30 min. The nuclei fragments were stained using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as a substrate for the peroxidase.

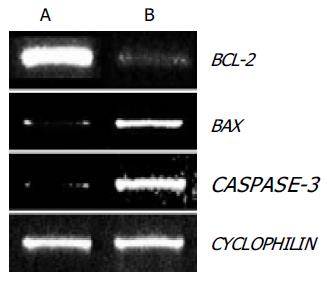

Total RNA was isolated from SNU-C4 cells with RNAzolTMB (TEL-TEST, Friendswood, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. cDNA was produced using random hexamer primers and reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The corresponding cDNA was amplified in PCR reactions with following primers for BCL-2 (5’-TCC GTG CCT GAC TTT AGC AAG CTG-3’; 5’-GGA ATC CCA ACC AGA GAT CTC AA-3’), BAX (5’-AGA TGA ACT GGA TAG CAA TAT GGA-3’, 5’-CCA CCC TGG TCT TGG ATC CAG ACA-3’), and for CASPASE-3 (5’-CTT GGT AGA TCG GCC ATC TGA AAC-3’; 5’-GGT CCC GTA CAG GTG TGC TTC GAC-3’). CYCLOPHILIN (5’-ACC CCA CCG TGT TCT TCG AC-3’, 5’-CAT TTG CCA TGG ACA AGA TG-3’) was used as an internal standard. The annealing temperature was 50°C for BCL-2 and BAX, 57°C for CASPASE-3, and 56°C for CYCLOPHILIN. The amplified fragment sizes were respectively 333 bp (for BCL-2), 260 bp (for BAX), 405 bp (for CASPASE-3), and 300 bp (for CYCLOPHILIN). The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1.2% agarose gel, and stained with ethidium bromide. The PCR amplification was performed in 30 cycles for BCL-2, BAX, CASPASE-3, and 24 cycles for CYCLOPHILIN.

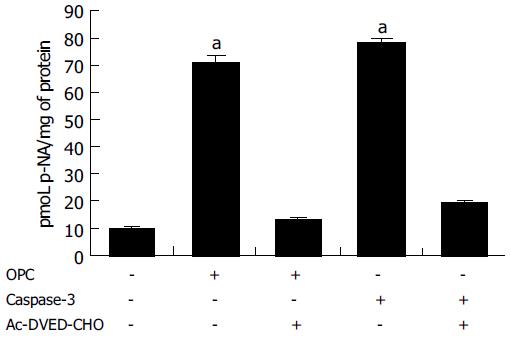

Because caspase-3 is a key step in the regulation of apoptosis, caspase-3 activity was measured using a commercially availabe kit. Cells were incubated with OPC (100 µg/mL) for 24 h, and were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed. Then the lysates were incubated overnight with caspase-3 substrate (Ac-DVED-pNA) at 37°C, and absorbance at 405 nm was measured using a 96-well microtiter plate reader. As a positive control, recombinant caspase-3 protein was incubated with a substrate. As an inhibitor of caspase-3, Ac-DVED-CHO was used.

Results were expressed as mean±SE. All experiments were done in triplicate. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis using SPSS. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

The MTT assay was used to measure the viability of SNU- C4 cells exposed to OPC. As shown in Figure 1, the viabilities of cells exposed to OPC at concentrations of 10, 50, 100, and 500 µg/mL for 24 h, were 94.03 ± 0.21%, 81.17 ± 0.35%, 35.61 ± 5.53%, and 21.24 ± 1.31% of control value, respectively. The cytotoxic effect of OPC on SNU-C4 cells appeared in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1).

The morphological changes, DAPI staining, and TUNEL reaction were studied to investigate whether cell death was a result of apoptosis in SNU-C4 cells. Cells treated with OPC (100 µg/mL) for 24 h revealed shrinkage of cells through phase-contrast microscope (Figure 2B). To characterize the cell death induced by OPC, nuclear morphology of dying cells were examined with a fluorescent DNA-binding agent, DAPI. Cells treated with OPC displayed typical morphological features of apoptotic cells, with condensed and fragmented nuclei (Figure 2D). The induction of apoptosis by OPC was examined by in situ apoptosis detection. TUNEL assay, based on labeling of DNA strand breaks generated during apoptosis, confirmed that OPC induces apoptosis in SNU-C4 cells (Figure 2F).

To examine the role of these BCL-2 family genes in OPC-induced apoptosis, the expression of BCL-2 and BAX genes were evaluated in SNU-C4 cells using RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 3, BCL-2 gene expression was markedly decreased and BAX gene expression was highly increased with OPC treatment.

Since caspase-3 plays the critical role in apoptosis, the CASPASE-3 gene expression and caspase-3 enzyme activity were determined through RT-PCR and caspase-3 activity assay. The expression of CASPASE-3 was markedly increased after OPC treatment (Figure 3). The caspase-3 activity was measured using specific substrate (Ac-DEVD-pNA). Caspase-3 protein was used as the positive control, and a caspase inhibitor, Ac-DEVD-CHO was the negative control. As illustrated in Figure 4, caspase-3 specific activity was increased by OPC treatment.

Colorectal cancer is the most common of visceral malignancies with the third most common cause of cancer-related mortality in the West[19]. Despite improvements in the management of the colon cancer patient, there is little change in survival rates over the past 50 years[20]. Tumor cells differ from normal cells in their non-responsiveness to normal growth-controlling mechanisms. Current chemotherapeutic drugs try to change the biological properties of cancer cells that continuously divide and grow[21].

In the present study, we investigated the effect of OPC-induced apoptosis on human colorectal cancer cell line SNU-C4 to define the pharmacological basis for anticancer effects and its mechanism of OPC. OPC, extracted from grape seed showed potent anti-oxidant effects in numerous studies[22-25]. Additionally, proanthocyanidins exhibit anti-carcinogenic[3-6], anti-inflammatory[7,8], anti-allergic[9,10], cardioprotective activities[14], as well as being inhibitors of the phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase and lipooxygenase3[26].

Recently, Carnésecchi et al[6] reported anti-proliferative effects of procyanidins from cocoa extracts on the growth inhibition of human colonic cancer cell with a blockade of the cell cycle at the G2/M phase. OPC have demonstrated the anti-proliferative effect in murine Hepa-1c1c7[26], cytotoxic effects on selected human cancer cells, including cultured MCF-7 breast cancer, CRL 1739 gastric adenocarcinoma and A-427 lung cancer cells[5]. These reports demonstrated that OPC influences cancer cell proliferation and growth.

The results of present study demonstrated that OPC induce cytotoxic effect measured by the cell viability on SNU-C4 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1). SNU-C4 cells also showed apoptotic morphological change of nuclear shrinkage, chromatin condensation, irregularity in shape and retraction by the OPC treatment (Figure 2). In this study, we observed the apoptotic morphology of cellular bodies and the chromatin condensation by DAPI staining (Figure 2). It is known that DNA strand breaks occur during the process of apoptosis, and the nicks in DNA molecules can be detected by the apoptotic status of cells through TUNEL assay[27]. In the present study, typical TUNEL distinction of apoptosis was observed in OPC-treated cells (Figure 2).

In a number of studies, it has been documented that the progress of apoptosis is regulated by the expression of several genes, one of these genes is a member of the BCL-2 family[28]. The BCL-2 family can be classified into two functionally different groups: anti-apoptotic genes and pro-apoptotic genes. BCL-2, an anti-apoptotic gene, is known for regulating the apoptotic pathways and protecting cell death, while BAX, a pro-apoptotic gene of the family, is expressed abundantly and selectively during apoptosis, promoting cell death[29]. Our data showed that OPC altered the expression of apoptosis-regulating genes. BCL-2 gene expression decreased and BAX gene expression increased after OPC-treatment (Figure 3).

At the execution phase of apoptosis, a series of morphological and biochemical changes appear to have resulted from the action of caspases[30]. Caspase-3, in particular, is believed to be most commonly involved in the execution of apoptosis in various cell types[31], because it cleaves most of caspase-related substrates, including key proteins such as the nuclear enzyme PARP[32]. In our data, it is shown that the CASPASE-3 gene expression was increased (Figure 3) and the activity of caspase-3 was increased after OPC treatment (Figure 4). Based on the results, OPC appears to activate intracellular death-related pathways, leading to caspase-3 activation in SNU-C4 cells. Ye et al[5] revealed cytotoxicity of proanthocyanidins from grape seed compared between the human cancer cells with two normal cells, proanthocyanidins demonstrated selective cytotoxicity toward several cancer cells at the concentration of 25, 50 mg/L, while it enhances the growth and viability of the normal cells at the same concentration. Moreover, Joshi et al[33] demonstrated that grape seed proanthocyanidin, ameliorates the toxic effects associated with chemotherapeutic agents such as, 30 nmol/L idarubicin and 1 μg/mL 4-hydroxyperoxycyclophosphamide (4-HC) on normal human hepatocyte, Chang liver cells. These findings suggest that the treatment with OPC show low toxicity on normal cells, and it might have a novel anti-tumor effect on human colorectal cancer cells.

In conclusion, inhibitory effect of OPC on the proliferation of human colorectal cancer cells, SNU-C4 is mainly through apoptosis induced by CASPASE-3 related to BCL-2 families.

The authors are grateful to Doosan Biotech Institute (Yong-in, Korea).

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

Co-first-authors: Hae-Jeong Park

| 1. | Middleton E, Kandaswami C, Theoharides TC. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:673-751. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Jorge M, Silva RC, Darmon N, Fernandez Y, Mitjavila S. Oxy-gen free radical scavenger capacity in aqueous models of different procyanidins from grape seeds. J Agric Food Chem. 1991;39:1549-1552. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, Slowing KV, Thomas CF, Beecher CW, Fong HH, Farnsworth NR, Kinghorn AD, Mehta RG. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science. 1997;275:218-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3633] [Cited by in RCA: 3391] [Article Influence: 121.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | De Bruyne T, Pieters L, Witvrouw M, De Clercq E, Vanden Berghe D, Vlietinck AJ. Biological evaluation of proanthocyanidin dimers and related polyphenols. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:954-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ye X, Krohn RL, Liu W, Joshi SS, Kuszynski CA, McGinn TR, Bagchi M, Preuss HG, Stohs SJ, Bagchi D. The cytotoxic effects of a novel IH636 grape seed proanthocyanidin extract on cultured human cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 1999;196:99-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Carnésecchi S, Schneider Y, Lazarus SA, Coehlo D, Gossé F, Raul F. Flavanols and procyanidins of cocoa and chocolate inhibit growth and polyamine biosynthesis of human colonic cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2002;175:147-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Subarnas A, Wagner H. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of the proanthocyanidin shellegueain A from Polypodium feei METT. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:401-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li WG, Zhang XY, Wu YJ, Tian X. Anti-inflammatory effect and mechanism of proanthocyanidins from grape seeds. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2001;22:1117-1120. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Thoden JB, Taylor Ringia EA, Garrett JB, Gerlt JA, Holden HM, Rayment I. Evolution of enzymatic activity in the enolase superfamily: structural studies of the promiscuous o-succinylbenzoate synthase from Amycolatopsis. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5716-5727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pearce FL, Befus AD, Bienenstock J. Mucosal mast cells. III. Effect of quercetin and other flavonoids on antigen-induced histamine secretion from rat intestinal mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1984;73:819-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Mao TK, Powell J, Van de Water J, Keen CL, Schmitz HH, Hammerstone JF, Gershwin ME. The effect of cocoa procyanidins on the transcription and secretion of interleukin 1 beta in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Life Sci. 2000;66:1377-1386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bagchi D, Garg A, Krohn RL, Bagchi M, Tran MX, Stohs SJ. Oxygen free radical scavenging abilities of vitamins C and E, and a grape seed proanthocyanidin extract in vitro. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 1997;95:179-189. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Frémont L, Belguendouz L, Delpal S. Antioxidant activity of resveratrol and alcohol-free wine polyphenols related to LDL oxidation and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Life Sci. 1999;64:2511-2521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rein D, Paglieroni TG, Wun T, Pearson DA, Schmitz HH, Gosselin R, Keen CL. Cocoa inhibits platelet activation and function. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:30-35. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Depeint F, Gee JM, Williamson G, Johnson IT. Evidence for consistent patterns between flavonoid structures and cellular activities. Proc Nutr Soc. 2002;61:97-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Schmitt E, Sané AT, Steyaert A, Cimoli G, Bertrand R. The Bcl-xL and Bax-alpha control points: modulation of apoptosis induced by cancer chemotherapy and relation to TPCK-sensitive protease and caspase activation. Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;75:301-314. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Galati G, Teng S, Moridani MY, Chan TS, O'Brien PJ. Cancer chemoprevention and apoptosis mechanisms induced by dietary polyphenolics. Drug Metabol Drug Interact. 2000;17:311-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Je JJ, Shin HT, Chung SH, Lee JS, Kim SS, Shin HD, Jang MH, Kim YJ, Chung JH, Kim EH. Protective effects of Wuyaoshunqisan against H2O2-induced apoptosis on hippocampal cell line HiB5. Am J Chin Med. 2002;30:561-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics, 1999. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:8-31, 1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2345] [Cited by in RCA: 2206] [Article Influence: 84.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yeatman TJ, Chambers AF. Osteopontin and colon cancer progression. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:85-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kelloff GJ, Boone CW, Steele VE, Crowell JA, Lubet RA, Greenwald P, Hawk ET, Fay JR, Sigman CC. Mechanistic considerations in the evaluation of chemopreventive data. IARC Sci Publ. 1996;139:203-219. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Shi J, Yu J, Pohorly JE, Kakuda Y. Polyphenolics in grape seeds-biochemistry and functionality. J Med Food. 2003;6:291-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 460] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Scalbert A, Williamson G. Dietary intake and bioavailability of polyphenols. J Nutr. 2000;130:2073S-2085S. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Cos P, De Bruyne T, Hermans N, Apers S, Berghe DV, Vlietinck AJ. Proanthocyanidins in health care: current and new trends. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:1345-1359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fine AM. Oligomeric proanthocyanidin complexes: history, structure, and phytopharmaceutical applications. Altern Med Rev. 2000;5:144-151. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Matito C, Mastorakou F, Centelles JJ, Torres JL, Cascante M. Antiproliferative effect of antioxidant polyphenols from grape in murine Hepa-1c1c7. Eur J Nutr. 2003;42:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Qiao L, Hanif R, Sphicas E, Shiff SJ, Rigas B. Effect of aspirin on induction of apoptosis in HT-29 human colon adenocarcinoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:53-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2 gene family and the regulation of programmed cell death. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1693s-1700s. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Oltvai ZN, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell. 1993;74:609-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4399] [Cited by in RCA: 4503] [Article Influence: 140.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y. Caspases: enemies within. Science. 1998;281:1312-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5130] [Cited by in RCA: 5088] [Article Influence: 188.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Izban KF, Wrone-Smith T, Hsi ED, Schnitzer B, Quevedo ME, Alkan S. Characterization of the interleukin-1beta-converting enzyme/ced-3-family protease, caspase-3/CPP32, in Hodgkin's disease: lack of caspase-3 expression in nodular lymphocyte predominance Hodgkin's disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1439-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Nicholson DW, Ali A, Thornberry NA, Vaillancourt JP, Ding CK, Gallant M, Gareau Y, Griffin PR, Labelle M, Lazebnik YA. Identification and inhibition of the ICE/CED-3 protease necessary for mammalian apoptosis. Nature. 1995;376:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3009] [Cited by in RCA: 3156] [Article Influence: 105.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Joshi SS, Kuszynski CA, Bagchi M, Bagchi D. Chemopreventive effects of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract on Chang liver cells. Toxicology. 2000;155:83-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |