Published online Jul 21, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i27.4281

Revised: January 1, 2005

Accepted: January 5, 2005

Published online: July 21, 2005

Hemangiopericytoma is a rare tumor especially when it rises in the peritoneal cavity. We present a case of a 60-year-old woman with an isolated recurrent hemangiopericytoma of the liver. The patient presented with a palpable right upper quadrant abdominal mass, which occurred 7 years after undergoing resection of a malignant hemangiop-ericytoma arising from the greater omentum. She had not followed up 6 mo after surgery. Various imaging studies showed a single large, well-capsulated liver tumor with central necrosis, accompanied by hypervascularity typical of a vascular tumor. Preoperative laboratory HBsAg and anti-HCV workup were both negative. Under the impression of recurrent malignant hemangiopericytoma, right triseg-mentectomy was performed to completely resect the tumor. Pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of recurrent hemangiopericytoma. Even though the incidence of the hemangiopericytoma is relatively low, malignant hemangiopericytoma has a tendency to recur frequently after a long-term disease-free interval. Also, the recurrent hemangiopericytoma is not easily detected early during follow-up until it becomes symptomatic because there are no specific tumor markers, and because of the diversity with regard to site of recurrence. The authors suggest that Positron Emission Tomogram (PET) may be a useful tool for the detection of recurrent hemangiopericytoma. We describe herein some characteristics and behaviors of malignant hemangiopericytoma, particularly after surgical resection.

- Citation: Kim BW, Wang HJ, Jeong IH, Ahn SI, Kim MW. Metastatic liver cancer: A rare case. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(27): 4281-4284

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i27/4281.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i27.4281

Hemangiopericytoma was first described in 1942 by Stout and Murray, and approximately 1 000 cases have been reported to date in the literature. Hemangiopericytomas arise from the pericyte of Zimmermann, and although it may occur in any part of the human body, the frequency of occurrence has been reported to be the lower extremities, pelvic cavity, retro-peritoneum, thoracic cavity, and upper extremities, in descending order. Most tumors have been reported to occur in the deep portions of the body, and those arising within the peritoneum are rare[1]. Generally, although hemangiopericytomas arising in the peritoneal cavity show better prognosis compared to adenocarcinomas that occur in the gastrointestinal tract, surgery seems to be the only effective mode of therapy.

Histologically benign hemangiopericytomas are known to be curable by complete surgical resection, while the malignant type, albeit characterized by slow growth, has been known to recur frequently after curative surgical resection. Another reported characteristic of hemangiopericytomas is the development of non-islet-cell-tumor hypoglycemia in the latter phase of the natural course[1], and this has been related to the production of the insulin-like growth factor II by the tumor[2,3]. Malignant hemangiopericytomas are characterized by an indolent rate of growth, but recurrence has been demonstrated in more than half of the cases which had been followed up. In addition, the diversity of the sites of recurrence via hematological and lymphatic routes and lack of specific tumor markers has contributed to the difficulty in detecting recurrent disease. The lungs have been shown to be the most common distal site of recurrence, while other sites include the brain, scalp, chest wall, liver, subcutaneous lymph node, gastrointestinal tract, and ovaries[4,5].

The authors report a surgically treated case of hemangi-opericytoma of the greater omentum, and which recurred as a metachronous solitary liver metastasis 7 years after complete resection. We also suggest the employment of the positron emission tomography (PET) method as a useful tool in the post-operative follow-up of patients with a history of hemangiopericytomas, as there is no other definite established mode of follow-up.

A gravida 6, para 5, at present 60-years old, female patient had presented with a palpable lower abdominal mass referred initially from a private gynecologic clinic in March 1997, under the impression of a myoma of the uterus. Her past gynecologic history showed that she had entered menopause at 49 years of age. Physical examination showed a mobile, solid mass in the lower abdomen. Transvaginal ultrasonography demonstrated that the mass did not originate from the uterus. A magnetic resonance imaging was performed to determine if the mass was of ovarian origin, and which showed that an 8 cm sized, solitary mass of unknown origin was present in the pelvic cavity. There was no evidence of lymph node enlargement. The tumor markers β-HCG, CA19-9, CA-125, CEA were all within the normal range. The patient subsequently underwent exploratory laparotomy under the impression of a possible ovarian malignancy, upon which a 10 cm×8 cm×7 cm mass originating from the greater omentum was observed. There was no gross evidence of other pathology such as surrounding adhesions or lymph node pathology, and the patient consequently underwent tumor excision including a portion of the omentum. Pathologic examination revealed necrosis in the central portion of the tumor, atypical hyperplasia of spindle-shaped tumor cells, and five mitoses per 10 HPF, suggestive of a malignant hemangiopericytoma. The patient was discharged 7 d after surgery and no further adjuvant anti-cancer therapy was administered. She had not followed up 6 mo after surgery.

The patient was asymptomatic until October 2004, when she began to complain of a palpable right upper quadrant mass, and she visited our department for evaluation. Initial abdominal computerized tomography (CT) demonstrated a large mass in the right hepatic lobe. To ascertain whether this lesion was a possible hepatocellular carcinoma, a common cause of liver tumors in Korea, viral marker studies were conducted, and which showed HBsAg (-), anti-HBs (+), anti-HBc (+), and anti-HCV (-). Also, the tumor markers AFP, CEA, CA19-9, and CA125 were all within normal limits. Plain chest X-ray was also normal.

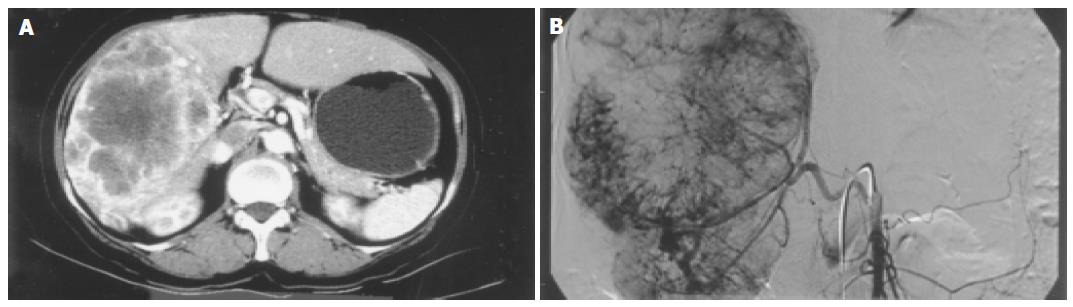

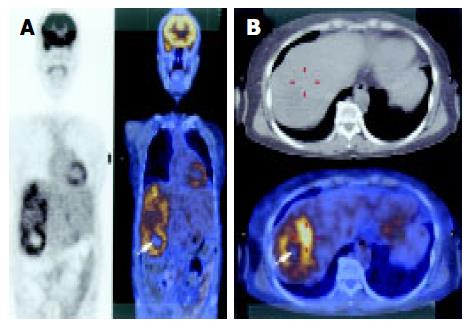

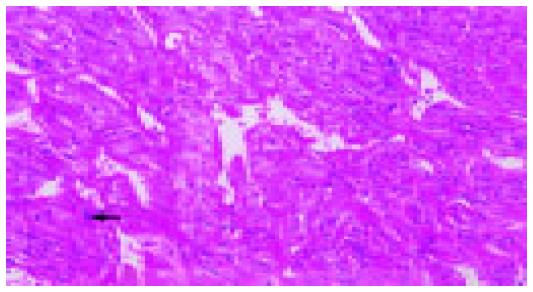

Abdominal CT scan showed that the tumor was of a hypervascular nature, with active contrasting from the periphery of the tumor in the arterial phase, and remaining contrast in the delayed phase suggesting a tumor of vascular origin. The hepatic artery angiogram confirmed that the tumor was hypervascular, with vessels from major arteries providing branches surrounding and entering into the deep portions of the tumor (Figure 1). These findings were highly suggestive of a recurrent malignant hemangiopericytoma. To determine the presence of any distant metastatic lesion, a head and neck CT (normal) was performed, while the 18F-FDG PET scan showed a standardized uptake value (SUV) of 4.8 in the right hepatic lobe indicative of 18F-FDG uptake. There were no other suspicious sites other than the liver (Figure 2). The patient therefore underwent laparotomy and right trisegmentectomy of the liver under the impression of recurrent malignant hemangiopericytoma. Gross findings showed a 15 cm, large solitary sarcomatous lesion with central necrosis. Microscopic examination of the tumor confirmed the presence of malignant hemang-iopericytoma identical to that of the lesion of 1997, with free resection margins (Figures 3 and 4). The patient was discharged on the 20th postoperative day without comp-lications.

Hemangiopericytomas primarily occurring in the abdominal cavity are very rare, and only 12 cases in the world-wide literature have reported those occurring in the greater omentum. It is thought that surgical removal of the tumor is the most effective mode of therapy for hemangiopericytomas, but as yet there is no established range of surgical resection for malignant types that occur in the abdomen. As demonstrated in our case, in light of the fact that secondary surgery confirmed recurrent metastatic liver tumor 7 years after initial simple excision, and that there was no local recurrence in the omentum and the peritoneal cavity, we do not feel that complete anatomical removal of the total greater omentum would lead to superior prognosis compared to simple excision only. This finding is similar to previously reported cases of greater omental hemangiopericytomas[6].

Grossly, malignant hemangiopericytomas have been reported usually as a solitary lesion, but in some series, several hundred, multiple nodules have also been observed[7]. In most cases, the tumor is observed as smoothly encapsulated, while the areas where the vessels enter into the tumor surface are characterized as irregular due to local tumor retraction. As hemangiopericytomas are hypervascular tumors, angiography demonstrates a feature of numerous feeding vessels surrounding and entering into the tumor, sometimes being observed as multiple cork-screw type feeding vessels. These findings, however, are not common findings, and are not highly regarded as a distinctive diagnostic feature[8,9]. Moreover, it is difficult to ascertain both a diagnosis of hemangiopericytoma and malignant characteristic with these radiological and gross findings alone.

Microscopic observation of H&E staining demonstrates numerous neovascularized vessels within a highly concentrated area of tumor cells, and which also frequently show a stag-horn feature. The tumor cells are mostly spindle-shaped, but may be spherical or other shapes, the nuclear to cytoplasm ratio is increased, while the cytoplasm is pale staining. Differential diagnosis includes glomus tumor, fibrous histiocytoma, synovial sarcoma, and mesenchymal sarcoma, and advances in immunohistochemical techniques usually allows differentiation from a malignant hemangiopericytoma. It has been reported in the previous literature that malignant hemangiopericytomas comprise about half of all cases, and that after local excision and long-term follow-up, approximately 60% of patients experience local or distant recurrence[4]. The disease-free interval has been reported to vary markedly between 2 mo and 26 years[10]. Specific features that qualify a hemangiopericytoma as a malignant lesion are more than four mitoses per 10 HPF, pleomorphic cells with abnormal chromatin pattern, and accompanied by either central tumor necrosis or intra-tumoral hemorrhage.

Observations of previous data regarding hemangio-pericytomas arising in the greater omentum have shown that the presence of more than four mitoses per 10 HPF is closely related to recurrence of disease. Also, the number of increased mitoses has also been suggested to be related with increased tumor size, and that tumors of more than 20 cm in diameter imply poor prognosis[6].

Other modes of therapy for malignant hemangiopericytoma may consist of anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy for residual or metastatic tumors[11,12], and these are usually the preferred mode of adjuvant therapy after surgery because of limited efficacy.

From the clinical perspective, compared to other common malignant tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, malignant hemangiopericytomas have a comparatively longer disease-free interval after surgical resection and an indolent natural history[13]. However, it should be mentioned that in many cases of recurrent disease after a long disease-free interval, it is common that either the qualified gastrointestinal surgeon concludes that the disease has been completely cured after a certain length of follow-up, or that the patient refuses further follow-up. This is also reflected in our case, whereby the patient presented with a recurred large intra-abdominal mass, or with related cancer symptoms such as hypoglycemia.

Another difficulty involving postoperative management of hemangiopericytoma is that since there is no established follow-up protocol after surgery, the length of follow-up and the diagnostic methods employed varies from surgeon to surgeon. Moreover, the absence of specific tumor markers makes it all the more difficult to detect recurrent disease. The authors of this study suggest that the PET scan is a valid, non-invasive diagnostic procedure in the ascertainment of recurrent malignant hemangiopericytoma. This may be particularly true in patients where if the preoperative PET demonstrates a hemangiopericytoma, the presence of a recurrent tumor of a similar character will be detected by PET in the follow-up. However, it should be noted that there may be differences in the degree of uptake between histologically identical hemangiopericytomas. In our case 18F-FDG uptake was increased within the tumor, but other series have shown that 11C-methionine and 15O-H2O uptake was increased rather than 18F-FDG[14]. That report is different from ours, so we think further evaluations about useful radio-isotope of PET for malignant hemangiopericytoma are needed. Another study suggested the correlation between the high uptake of 18F-FDG in hemangiopericytomas and poor prognosis[15]. Consequently, it is the opinion of the authors that such variable uptakes by malignant hemangiopericytoma as seen in PET scans contribute more to the detection of recurrent disease after surgical removal, rather than to the establishment of preoperative differential diagnosis. Also, the PET scans the whole body, and therefore allows detection of recurrent hemangiopericytoma, which has a wide pattern of recurrence.

In conclusion, although the pattern of recurrent malignant hemangiopericytoma is diverse, surgical intervention after early detection may allow another long disease-free period. For this to be accomplished, long-term follow-up is imperative, and we suggest that yearly PET scans are useful in attaining this goal.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Mattera D, Capuano G, Colao A, Pivonello R, Manguso F, Puzziello A, D'Agostino L. Increased IGF-I: IGFBP-3 ratio in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2003;59:699-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sohda T, Yun K. Insulin-like growth factor II expression in primary meningeal hemangiopericytoma and its metastasis to the liver accompanied by hypoglycemia. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:858-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Grunenberger F, Bachellier P, Chenard MP, Massard G, Caraman PL, Perrin E, Zapf J, Jaeck D, Schlienger JL. Hepatic and pulmonary metastases from a meningeal hemangiopericytoma and severe hypoglycemia due to abnormal secretion of insulin-like growth factor: a case report. Cancer. 1999;85:2245-2248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | McMaster MJ, Soule EH, Ivins JC. Hemangiopericytoma. A clinicopathologic study and long-term followup of 60 patients. Cancer. 1975;36:2232-2244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Begum M, Katabuchi H, Tashiro H, Suenaga Y, Okamura H. A case of metastatic malignant hemangiopericytoma of the ovary: recurrence after a period of 17 years from intracranial tumor. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:510-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kaneko K, Shirai Y, Wakai T, Hasegawa G, Kaneko I, Hatakeyama K. Hemangiopericytoma arising in the greater omentum: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:722-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Matsuda S, Usui M, Sakurai H, Suzuki H, Ogura Y, Shiraishi T. Insulin-like growth factor II-producing intra-abdominal hemangiopericytoma associated with hypoglycemia. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:851-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marc JA, Takei Y, Schechter MM, Hoffman JC. Intracranial hemangiopericytomas. Angiography, pathology and differential diagnosis. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;125:823-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guthrie BL, Ebersold MJ, Scheithauer BW, Shaw EG. Meningeal hemangiopericytoma: histopathological features, treatment, and long-term follow-up of 44 cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:514-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schirger A, Uihlein A, Parker HL, Kernohan JW. Hemangiopericytoma recurring after 26 years; report of case. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1958;33:347-352. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Wong PP, Yagoda A. Chemotherapy of malignant hemangiopericytoma. Cancer. 1978;41:1256-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Staples JJ, Robinson RA, Wen BC, Hussey DH. Hemangiopericytoma--the role of radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;19:445-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Spitz FR, Bouvet M, Pisters PW, Pollock RE, Feig BW. Hemangiopericytoma: a 20-year single-institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:350-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kracht LW, Bauer A, Herholz K, Terstegge K, Friese M, Schröder R, Heiss WD. Positron emission tomography in a case of intracranial hemangiopericytoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23:365-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |