Published online Jun 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i24.3714

Revised: October 12, 2004

Accepted: December 23, 2004

Published online: June 28, 2005

AIM: To report the clinical experiences in the application of clip-assisted endoscopic method for nasoenteric feeding in patients with gastroparesis and patients with gastroesophageal wounds, and to compare the efficacy of nasoenteric feeding in these two indications.

METHODS: From April 2002 to January 2004, 21 consecutive patients with gastroparesis or gastroesophageal wounds were enrolled and received nasoenteric feeding for nutritional support. A clip-assisted method was used to place the nasoenteric tubes. Outcomes in the two groups were compared with respect to the successful rate of enteral feeding, percentage of recommended energy intake (REI), and complication rates.

RESULTS: The gastroparesis group included 13 patients with major burns (n = 7), trauma (n = 2), congestive heart failure (n = 2) and post-surgery gastric stasis syndrome (n = 2). The esophageogastric wound group included eight patients with tracheoesophageal fistula (n = 2) and wound leakage following gastric surgery (n = 6). Two study groups were similar in feeding successful rates (84.6% vs 75.0%). There were also no differences in the percentage of REI between groups (79.4% vs 78.6%). Additionally, no complications occurred in any of the study groups.

CONCLUSION: Nasoenteric feeding is a useful method to provide nutritional support to most of the patients with gastroparesis who cannot tolerate nasogastric tube feeding and to the cases who need bypass feeding for esophageogastric wounds.

- Citation: Wu CJ, Hsu PI, Lo GH, Shie CB, Lo CC, Wang EM, Lin CK, Chen WC, Cheng LC, Yu HC, Chan YC, Lai KH. Clinical application of clip-assisted endoscopic method for nasoenteric feeding in patients with gastroparesis and gastroesophageal wounds. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(24): 3714-3718

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i24/3714.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i24.3714

The maintenance of appropriate nutrition in patients with acute and chronic illness is well recognized as a fundamental part of medical and surgical care. Malnourished patients have poor clinical outcomes, more complications and infections, and use more resources than well-nourished patients[1-3]. Although parenteral nutrition may improve clinical outcomes in patients with short bowel syndrome and in post-operative patients with esophageal or gastric cancers, its complications such as catheter sepsis, venous thrombosis, hyperglycemia, catheter embolism, and pneumothorax are the major disadvantages. Thus, enteral nutrition should be employed in preference to parenteral nutrition whenever possible because of its lower cost, less complications, and lower rates of infection[4,5].

Gastric feeding has a number of advantages. It is more physiological, easier to begin, and more convenient. Nonetheless, the main disadvantages of gastric feeding are encountered in patients with delayed gastric emptying and those at risk for aspiration, and tracheoesophageal fistula[6]. The incidence of intolerance to nasogastric feeding in critically ill patients had been reported up to 60%[7]. An alternative to nasogastric feeding is post-pyloric nutrition because small bowel function is often preserved in critically ill patients[8,9]. Unfortunately, besides, blind placements of post-pyloric feeding tubes have variable success rates, ranging from 35% to 100% depending on the method used and the experience of the operator[10-17], and none has gained widespread acceptance. Therefore, we developed a clip-assisted endoscopic method whereby nasoenteric tube can be reliably delivered into the distal duodenum or proximal jejunum[18].

The aims of this study were to report the clinical experiences in the application of nasoenteric feeding in patients with gastroparesis and patients with esophageogastric lesions, and to compare the efficacy of nasoenteric feeding in these two major indications.

From April 2002 to January 2004, 21 consecutive patients with gastroparesis or esophageogastric lesions were enrolled in this study. The gastroparesis was defined as the residual food in the stomach at 4 h after nasogastric feeding was more than 50% of total initial feeding amount. The esophageogastric wounds group included patients with perforated esophageal or gastric lesions due to trauma or operation. Nasoenteric feeding was performed in these patients to bypass wounds and to provide adequate nutritional support. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. This study was approved by the Human Medical Research Committee of the Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

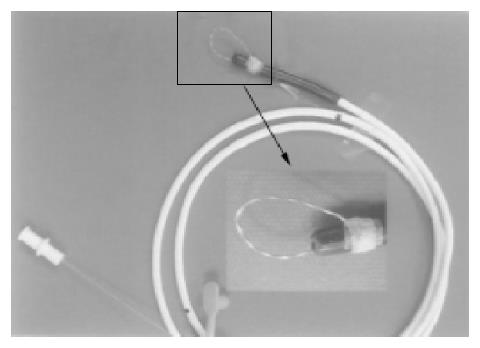

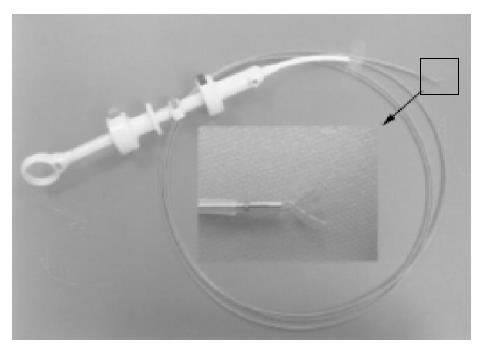

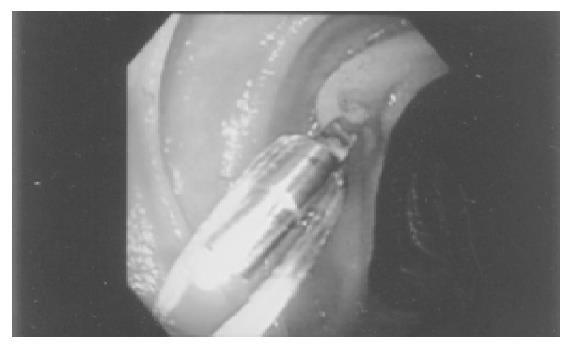

Clip-assisted endoscopic method[18] was applied to place feeding tubes in all the patients. A HX-5LR clip-fixing device (Olympus Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and a front viewing videoscope (Olympus GIF-XQ 40 and GIF-XQ 240) were used. The feeding tube (FlexifloR, Abbott, USA) had a hole on the tip and two adjacent side holes. A 3-0 silk suture was sewn through the distal hole and one adjacent side hole (Figure 1). The styleted feeding tube was then well lubricated with lidocaine 2% jelly (XylocaineR, Astrazeneca, Sodertalje, Sweden) and inserted into the stomach via nostril. The endoscope was inserted through the oropharynx and advanced into the stomach. A clip was fixed on a clip application device (Figure 2) which was then passed through the working channel of the endoscope. The clip was projected from the plastic sheath of the clip application device and grasped the 3-0 suture ring. The sheath was then withdrawn into the distal tip of the endoscopic working channel. The endoscope was advanced with the feeding tube through the pylorus to the greatest achievable depth of insertion. The clip was attached to the bowel wall by grasping a mucosal fold (Figure 3). The endoscope was then withdrawn from distal duodenum or proximal jejunum. Clip attachment and tube position were confirmed radiographically (Figure 4).

The recommended energy intake (REI) of each patient was calculated by Ireton-Jones equation. Tube feeding was commenced at 20 mL/h and increased progressively to REI over 48 h. Serum albumin was checked before enteral feeding, every 3 d after enteral feeding and when the tube was removed. During the course of feeding, tubes were regularly flushed every 6 h to prevent clogging of tubes.

Data regarding age, sex, underlying diseases, indications for nasoenteric feeding, daily intake of energy, daily body weight and serum albumin levels were recorded. We evaluated the following parameters: (1) successful rate of nasoenteric feeding; (2) percentage of energy intake; (3) change in body weight; (4) change in serum albumin level; (5) tube migration; (6) tube occlusion; and (7) complications of enteral feeding (e.g., bowel necrosis, bleeding, and perforation). The success of nasoenteric feeding was defined as the quantity of energy intake was more than 60% of REI.

Statistical tests were performed using SPSS system. One-sample t-tests were used to compare the baseline characteristics. Paired t-test was used to compare the pre- and post-feeding serum albumin and body weight. χ2 test was used to compare between groups. Differences were considered significant at P<0.05. The data were present as mean±SD.

The gastroparesis group included 13 patients with major burns (n = 7), trauma (n = 2), congestive heart failure (n = 2), and post-gastrtic surgery stasis syndrome (n = 2). The esophageogastric wound group included eight patients with tracheoesophageal fistula (n = 2) and wound leakage following gastric surgery (n = 6).

Data on clinical characteristics of patients at study are summarized in Table 1. The two groups were comparable with regard to age, gender, pre-feeding body weight and serum albumin levels. Endoscopic placement of feeding tube was successfully achieved in all of the attempts in both groups (successful rate of tube placement: 100% vs 100%).

| Gastroparesis (n = 13) | Esophageogastric wound (n = 8) | P | |

| Age (yr) (SD) | 60.7±22.1 | 70.1±14.0 | 0.126 |

| Gender (m:f) | 10:3 | 4:4 | |

| Body weight before feeding (kg) (SD) | 62.9±19.8 | 64.9±14.0 | 0.227 |

| Serum albumin before feeding (g/dL) (SD) | 3.0±0.4 | 2.4±0.4 | 0.840 |

Treatment results are shown in Table 2. There were no differences in the quantities of energy intake between groups (79% vs 79%). The feeding successful rates were 85% and 75% in the gastroparesis group and esophageogastric wound group, respectively. Two out of eight patients in the bypass wound group failed to be fed more than 60% of REI. The two patients died from sepsis with multiple organ failure. Two out of thirteen patients in the gastroparesis group failed to be fed more than 60%, and they finally expired due to sepsis with multiple organ failure. During follow-up, no spontaneous tube migration was observed. The mean durations of nasoenteric feeding were 15.2±10.5 and 22.0±14.1 d in the former and latter groups, respectively (P = 0.369). There were no complications related to nasoenteric feeding in both groups. However, tube occlusion due to clogging occurred in six patients in the gastroparesis group and one patient in the esophageogastric wound group. The tube occlusion rates were similar between groups (46.2% vs 12.5%, P = 0.174).

| Gastroparesis (n = 13) | Esophageogastric wound group (n = 8) | P | |

| Energy intake | |||

| REI (kcal) | 2346.2±674.2 | 1682.8±210.2 | 0.005 |

| Provided energy support (kcal) | 1800.0±463.7 | 1325.0±341.2 | 0.581 |

| Quantity of energy intake | 79±15% | 79±18% | 0.220 |

| Feeding success rate | 85% (11/13) | 75% (6/8) | 0.32 |

| Body weight (kg) | |||

| Pre-treatment | 62.9±19.8 | 64.9±14.0 | 0.227 |

| Post-treatment | 63.8±18.5 | 70.8±19.4 | 0.871 |

| Albumin level (g/dL) | |||

| Pre-treatment | 3.0±0.4 | 2.4±0.4 | 0.840 |

| Post-treatment | 3.1±0.5 | 2.6±0.3 | 0.227 |

| Tube occlusion rate | 46% (6/13) | 13% (1/8) | 0.174 |

| Complication rate | 0% | 0% | |

| Feeding time (d) | 15.2±10.5 | 22.0±14.1 | 0.369 |

| Procedure time (min) | 26.8±7.4 | 25.0±6.6 | 0.588 |

| Mortality rate | 30% (4/13) | 50% (4/8) | 0.646 |

In the gastroparesis group, pre-feeding and post-feeding serum albumin were 3.0±0.4 and 2.4±0.4 g/dL, respectively. There were no differences in albumin levels before and after nasoenteric feeding. In the esophageogastric wound group, the serum albumin levels also did not change following nasoenteric feeding. Additionally, there were no differences in pre-feeding and post-feeding serum albumin levels between gastroparesis and esophageogastric wound group (P = 0.840 and 0.227, respectively). Furthermore, no significant differences in body weight between groups were observed before and after nasoenteric feeding.

Adequate nutrition is important for clinical improvement of the critically ill patients. However, malnutrition is a common problem affecting up to 40% of hospitalized patients[19]. Compared with parenteral nutrition, enteral feeding is less expensive and is associated with fewer serious complications[20]. Additionally, it may prevent gut mucosal atrophy and increase gastrointestinal immune function. Nasoenteric feeding is indicated in a number of medical conditions, such as recurrent pulmonary aspiration due to gastroesophageal reflux, complicated pancreatitis resulting from burns or other acute stress conditions. Sefton et al[21], reported that nasogastric feeding was successful in only 41% of patients with major burns, with gastroparesis as the major cause of feeding failure. Nonetheless, most of the patients (80%) with failure of nasogastric feeding could be successfully fed by nasoenteric tubes. In the present study, five out of seven patients with major burns in whom nasogastric feeding failed were successfully fed by nasoenteric feeding.

In addition to major burns, gastric stasis also occurred in trauma, congestive heart failure and post-surgery gastric stasis syndrome. In the present study, one patient with gastric adenocarcinoma and another patient with jejunal tumor developed post-surgery gastric stasis syndrome. The gastroparesis of these patients were probably due to chronic obstruction of gastrointestinal tracts and acute surgical stress. Both of them could be successfully treated by nasoenteric feeding. Weaning from nasoenteric feeding was successful on 31 and 47 d following surgery, and oral feeding was reintroduced successfully in both cases. Our experiences suggest that nasoenteric feeding is a good choice for nutrition support to patients with post-surgery gastric stasis syndrome.

In our hospital, we also applied nasoenteric feeding for temporary nutritional support to patients with esophageogastric lesions. In the present study, most of the esophageogastric lesions resulted from wound leakage following surgery for complicated peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal tumor. Nasoenteric feeding could bypass esophageogastric wounds and provide adequate nutrition in 75% of patients.

Several non-surgical methods have been designed for placement of nasoenteric feeding tube beyond the pylorus. One method involves blind placement of a tungsten weighted nasoenteral tube into the duodenum[22]. However, this method is time-consuming and unreliable. Fluoroscopy facilitates the placement of jejunal feeding tubes, but required radiologic support fluoroscopic machine at the side of the bed or transportation of the patient to the radiology department and exposure to radiations[23,24].

Endoscopically assisted intubation allows direct vision and is, therefore, a more practical approach. However, gastroenterologists are often frustrated in their efforts to deliver a feeding tube into the duodenum or proximal jejunum because of retrograde migration on withdrawal of the endoscope. We therefore developed a new method to fix the distal tip of the feeding tube in the duodenum or proximal jejunum by a metallic clip. This allowed the endoscope to be withdrawn without consequent retrograde migration of the feeding tube. Additionally, no spontaneous migration of tubes occurred after initial successful placement of nasoenteric tube in the 21 patients with nasoenteric feeding.

Hachisu et al[25], reported that the depth of the metallic clip’s grasp was limited to the muscularis mucosa in the human colon and esophagus. In this study, no bleeding or perforation due to intentional or accidental removal of clips was observed. Similar findings were also reported by Ginsberg et al[26]. Therefore, direct removal of clip-fixed nasoenteric tubes seems safe.

Tube clogging is one of the shortcomings of nasoenteric feeding and can occur because of crushed medication, inadequate flushing or precipitation of protein in the feeding tube[19]. Dysfunction of feeding tube occurred in 7 of the 21 sessions, probably due to the fine pores of feeding tubes and inadequate flushing.

In conclusion, clip-assisted endoscopic method is a reliable and safe modality for placing nasoenteric tubes into distal duodenum or proximal jejunum. Nasoenteric feeding is an useful method to provide nutritional support to most of the patients with gastroparesis who cannot tolerate nasogastric tube feeding and to the cases who need bypass feeding for esophageogastric wounds.

The authors express their deep appreciation to Dr. Wei-Lun Tsai, Wen-Chi Chen, Lung-Chih Cheng, Hsien-Chung Yu and Misses Min-Rong Huang for their assistance in the clinical follow up of the patients.

Co-first-authors: Chung-Jen Wu

Co-correspondents: Ping-I Hsu

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Naber TH, Schermer T, de Bree A, Nusteling K, Eggink L, Kruimel JW, Bakkeren J, van Heereveld H, Katan MB. Prevalence of malnutrition in nonsurgical hospitalized patients and its association with disease complications. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:1232-1239. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Martyn CN, Winter PD, Coles SJ, Edington J. Effect of nutritional status on use of health care resources by patients with chronic disease living in the community. Clin Nutr. 1998;17:119-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chima CS, Barco K, Dewitt ML, Maeda M, Teran JC, Mullen KD. Relationship of nutritional status to length of stay, hospital costs, and discharge status of patients hospitalized in the medicine service. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97:975-978; quiz 979-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kirby DF, Delegge MH, Fleming CR. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1282-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Heyland DK. Nutritional support in the critically ill patients. A critical review of the evidence. Crit Care Clin. 1998;14:423-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Van Stiegmann G, Pearlman NW. Simplified endoscopic placement of nasoenteral feeding tubes. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:349-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hiebert JM, Brown A, Anderson RG, Halfacre S, Rodeheaver GT, Edlich RF. Comparison of continuous vs intermittent tube feedings in adult burn patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1981;5:73-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dive A, Moulart M, Jonard P, Jamart J, Mahieu P. Gastroduodenal motility in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a manometric study. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:441-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Montecalvo MA, Steger KA, Farber HW, Smith BF, Dennis RC, Fitzpatrick GF, Pollack SD, Korsberg TZ, Birkett DH, Hirsch EF. Nutritional outcome and pneumonia in critical care patients randomized to gastric versus jejunal tube feedings. The Critical Care Research Team. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:1377-1387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zaloga GP. Bedside method for placing small bowel feeding tubes in critically ill patients. A prospective study. Chest. 1991;100:1643-1646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Thurlow PM. Bedside enteral feeding tube placement into duodenum and jejunum. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1986;10:104-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Levenson R, Turner WW, Dyson A, Zike L, Reisch J. Do weighted nasoenteric feeding tubes facilitate duodenal intubations? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1988;12:135-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Harrison AM, Clay B, Grant MJ, Sanders SV, Webster HF, Reading JC, Dean JM, Witte MK. Nonradiographic assessment of enteral feeding tube position. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:2055-2059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Spalding HK, Sullivan KJ, Soremi O, Gonzalez F, Goodwin SR. Bedside placement of transpyloric feeding tubes in the pediatric intensive care unit using gastric insufflation. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2041-2044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Botoman VA, Kirtland SH, Moss RL. A randomized study of a pH sensor feeding tube vs a standard feeding tube in patients requiring enteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1994;18:154-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dimand RJ, Veereman-Wauters G, Braner DA. Bedside placement of pH-guided transpyloric small bowel feeding tubes in critically ill infants and small children. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1997;21:112-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Slagt C, Innes R, Bihari D, Lawrence J, Shehabi Y. A novel method for insertion of post-pyloric feeding tubes at the bedside without endoscopic or fluoroscopic assistance: a prospective study. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:103-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shie CB, Hsu PI, Lo GH, Lin CK, Lo CC, Cheng JS, Lin CP, Chen WC, Wang EM, Chen IS. Clip-assisted endoscopic method for placement of a nasoenteric feeding tube into the distal duodenum. J Formos Med Assoc. 2003;102:514-516. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Pearce CB, Duncan HD. Enteral feeding. Nasogastric, nasojejunal, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, or jejunostomy: its indications and limitations. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:198-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Moore EE, Jones TN. Benefits of immediate jejunostomy feeding after major abdominal trauma--a prospective, randomized study. J Trauma. 1986;26:874-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sefton EJ, Boulton-Jones JR, Anderton D, Teahon K, Knights DT. Enteral feeding in patients with major burn injury: the use of nasojejunal feeding after the failure of nasogastric feeding. Burns. 2002;28:386-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Whatley K, Turner W, Day M. Transpyloric passage of feeding tubes. Nutr Suppl Serv. 1983;3:18-21. |

| 23. | Pobiel RS, Bisset GS, Pobiel MS. Nasojejunal feeding tube placement in children: four-year cumulative experience. Radiology. 1994;190:127-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Prager R, Laboy V, Venus B, Mathru M. Value of fluoroscopic assistance during transpyloric intubation. Crit Care Med. 1986;14:151-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hachisu T, Miyazaki S, Hamaguchi K. Endoscopic clip-marking of lesions using the newly developed HX-3L clip. Surg Endosc. 1989;3:142-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ginsberg GG, Lipman TO, Fleischer DE. Endoscopic clip-assisted placement of enteral feeding tubes. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:220-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |