Published online May 14, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i18.2844

Revised: November 9, 2004

Accepted: November 23, 2004

Published online: May 14, 2005

AIM: To investigate the relationship between encapsulating peritonitis and familial Mediterranean fever (FMF).

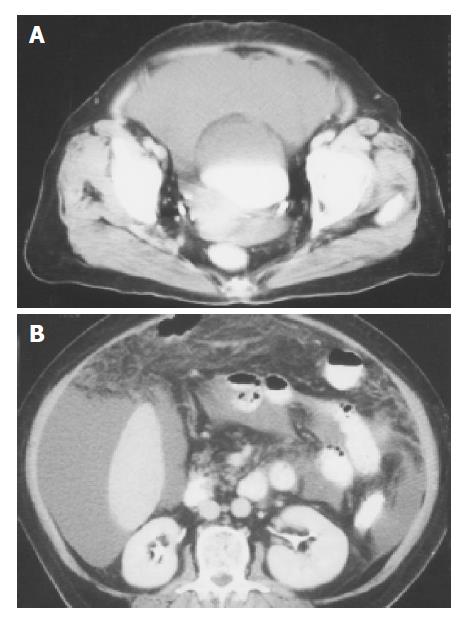

METHODS: The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes and laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed one year ago for cholelithiasis. Eleven months after the operation she developed massive ascites. Biochemical evaluation revealed hyperglycemia, mild Fe deficiency anemia, hypoalbuminemia and a CA-125 level of 2700 IU. Ascitic evaluation showed characteristics of exudation with a cell count of 580/mm3. Abdominal CT showed omental thickening and massive ascites. At exploratory laparotomy there was generalized thickening of the peritoneum and a laparoscopic clip encapsulated by fibrous tissue was found adherent to the uterus. Biopsies were negative for malignancy and a prophilactic total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingooophorectomy were performed.

RESULTS: The histopathological evaluation was compatible with chronic nonspecific findings and mild mesothelial proliferation and chronic inflammation at the uterine serosa and liver biopsy showed inactive cirrhosis.

CONCLUSION: The patient was evaluated as sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis induced by the laparoscopic clip acting as a foreign body. Due to the fact that the patient had FMF the immune response was probably exaggerated.

- Citation: Dabak R, Uygur-Bayramiçli O, Aydln DK, Dolapçloglu C, Gemici C, Erginel T, Turan C, Karadayl N. Encapsulating peritonitis and familial Mediterranean fever. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(18): 2844-2846

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i18/2844.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i18.2844

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an immunological disorder characterized by recurrent abdominal pain and polyserositis and is common in Mediterranean countries. Episodes of exudative peritonitis, pleuritis, arthritis and rarely inflammation of the organs may occur. Unnecessary laparotomies exacerbate accumulation of fibrotic adhesions caused by the disease itself. Ascites has been reported in FMF patients only after the development of secondary amyloidosis, which is seen mainly in patients who are not taking colchicine[1]. We hereby report an unusual cause of ascites in FMF and review the literature.

A 65-year-old female patient with a history of FMF for 20 years presented with massive ascites. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes for 5 years which was regulated with oral antidiabetics and a laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed one year ago for cholelithiasis. At the time of the operation she was not taking colchicine. There was no alcohol consumption or a history of hepatitis. Six months after the operation she felt a tenderness over the suprapubic region, and bloating developed all over the abdomen 11 mo after the operation. Besides the presence of dyspnea and anemia the abdomen was enlarged and she noticed a vaginal hemorrhagic discharge. An abdominal ultrasound revealed massive ascites, normal liver and splenic echogeneity and gynecological ultrasound did not show any abnormalities. Biochemical evaluation revealed a fasting blood glucose level of 220 mg/dL, normal renal function tests, mild Fe deficiency anemia, normal liver function tests, hypoalbuminemia, normal platelets and prothrombin time and a CA-125 level of 2700 U/mL (interval: 0-25 U/mL). Other tumor markers were normal. Ascitic evaluation showed characteristics of exudative ascites with a cell count of 580/mm3 and a predominance of lymphocytes with no malignant cells. Serum ascitic albumin gradient was 1.0. Cultures for bacteria and Mycobacterium tuberculosis were negative. The patient was negative for serum markers of hepatitis B and C viruses, and autoantibodies. Portal Doppler ultrasound, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and barium enema were normal. Abdominal CT showed minimal omental thickening and massive ascites (Figures 1A and 1B). We decided to perform an exploratory laparotomy in order to exclude tuberculous peritonitis and ovarian malignancy. At the operation there was thickening of the peritoneum in general and a laparoscopic clip encapsulated by fibrous tissue was found adherent to the uterus. Biopsies taken from the peritoneum, omentum, ovaries and fibrous tissue were negative for malignancy and a prophilactic total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingooophorectomy were performed. The histopathological evaluation of the peritoneum and omentum was compatible with chronic nonspecific findings and mild mesothelial proliferation. There was chronic inflammation at the uterine serosa and the liver biopsy showed inactive cirrhosis. In none of the biopsies taken from different organs there was a finding compatible with amyloidosis. The fibrous tissue surrounding the clip was accepted as a chronic reaction to the clip and the generalized thickening of the peritoneum was interpreted as a mild form of encapsulating peritonitis, which was probably induced by the foreign body namely the laparoscopic clip. Ascites developed again 10 d after the operation. Therefore, we started with 30 mg prednisolone and colchicine 1 mg/d and tapered the corticosteroids gradually in 6 wk. After this treatment ascites disappeared completely. In the early postoperative period the CA-125 level was still very high and decreased to normal levels gradually in three months with the disappearance of the ascites. The patient is still doing well after eight months of follow-up and there is no ascites.

Encapsulating peritonitis has been described in the literature as peritonitis chronica fibrosa incapsulata, sclerosing peritonitis, sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis[2] and more severe forms as abdominal cocoon[3]. The pathogenesis and etiology is not well known. Prolonged treatment with beta-adrenergic blockers, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematous, ventriculoperitoneal and peritoneovenous shunting, intraperitoneal instillation of drugs, and chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis[4] have been accused as causative agents.

Clinical picture is characterized by recurrent episodes of intestinal obstruction and abdominal mass but there may also be ascites[5]. For diagnosis, radiological evaluation is the mainstay but radiological findings are nonspecific and surgical confirmation is mostly necessary[6].

In the literature there is one case of encapsulating peritonitis in periodic disease, which had abdominal pain and a pseudocystic appearance in USG and CT, and surgical intervention was necessary for the diagnosis[7]. There is another report about previously unpublished peritoneal complications of familial paroxysmal polyserositis[8]. Our case is the third report of encapsulating peritonitis in association with FMF. It is interesting that this patient presented with ascites, but there were no signs of intestinal obstruction. This was probably due to the fact that the history of ascites was not very prolonged and adhesions have not been formed yet. The absence of amyloidosis but the presence of ascites has led us to look for another cause of ascites in FMF. The patient had stopped to take colchicine for the past two years because she did not have any abdominal attacks, but this may have led to the development of an exaggerated immunological response to the foreign body in the peritoneal cavity, namely laparoscopic clip. This laparoscopic clip acted as a chronic stimulus in the cavity and caused the chronic peritoneal inflammation and this was the triggering point for the encapsulating peritonitis. The resection of the clip together with the uterus eliminated this chronic stimulus and the immunosuppression of immunologic events of FMF with corticosteroids and colchicine has led to the disappearance of the ascites. It is well known that there are abnormalities of suppressor T lymphocytes, altered metabolism of lipoxygenase products of arachidonic acid and absence of a normal inhibitor of the complement-derived anaphylatoxin C5a[9].

This case confirmed the hypothesis that the elevation of CA-125, which is seen in peritoneal tuberculosis[10,11] and ovarian and endometrial malignancies[12,13], may also be due to the chronic peritoneal irritation. The regression of the level of CA-125 after the medical treatment is another evidence for this fact.

In summary encapsulating peritonitis although rare can also be due to some reason of chronic peritoneal irritation, and immunological disorders like FMF may facilitate the development of encapsulating peritonitis.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Robert P, Mc Cabe Jr. Immunologic disorders In: Brandt LJ, ed. Clinical practice of gastroenterology, philadelphia. Churchill Livingstone. 1999;. |

| 2. | Tsunoda T, Mochinaga N, Eto T, Furui J, Tomioka T, Takahara H. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis combined with peritoneal encapsulation. Arch Surg. 1993;128:353-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Deeb LS, Mourad FH, El-Zein YR, Uthman SM. Abdominal cocoon in a man: preoperative diagnosis and literature review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;26:148-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Holland P. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Clin Radiol. 1990;41:19-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Maguire D, Srinivasan P, O'Grady J, Rela M, Heaton ND. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Surg. 2001;182:151-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Krestin GP, Kacl G, Hauser M, Keusch G, Burger HR, Hoffmann R. Imaging diagnosis of sclerosing peritonitis and relation of radiologic signs to the extent of the disease. Abdom Imaging. 1995;20:414-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bellin MF, Deutsch JP, Bletry O, Langlois P, Bousquet JC, Cortez A, Godeau P, Grellet J. Encapsulating peritonitis in periodic disease. Apropos of a case studied by x-ray computed tomography. Ann Radiol (Paris). 1989;32:302-304. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Bitar E, Rizk A, Nasr W, Gédéon EM, Tabbara W. Familial paroxysmal polyserositis. Previously unpublished peritoneal complications. A case. Presse Med. 1985;14:586-588. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Wright DG. Familial Mediterranean Fever In. Bennett JC, Plum F,eds. Cecil, Textbook of Medicine, 20 th edition. Philadelphia: Saunders 1996; 907-908. |

| 10. | Bilgin T, Karabay A, Dolar E, Develioğlu OH. Peritoneal tuberculosis with pelvic abdominal mass, ascites and elevated CA 125 mimicking advanced ovarian carcinoma: a series of 10 cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11:290-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mas MR, Cömert B, Sağlamkaya U, Yamanel L, Kuzhan O, Ateşkan U, Kocabalkan F. CA-125; a new marker for diagnosis and follow-up of patients with tuberculous peritonitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:595-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sevinc A, Camci C, Turk HM, Buyukberber S. How to interpret serum CA 125 levels in patients with serosal involvement? A clinical dilemma. Oncology. 2003;65:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wilder JL, Pavlik E, Straughn JM, Kirby T, Higgins RV, DePriest PD, Ueland FR, Kryscio RJ, Whitley RJ, Nagell Jv. Clinical implications of a rising serum CA-125 within the normal range in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: a preliminary investigation. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:233-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |