Published online Apr 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i16.2467

Revised: March 5, 2003

Accepted: April 1, 2003

Published online: April 28, 2005

AIM: To evaluate the significance of extended radical operation and its indications.

METHODS: Between January 1995 and December 1998, 56 inpatients with pancreatic head cancer received operation. Among them 35 patients (group 1) experienced the Whipple operation, and 21 patients (group 2) received the extended radical operation. The 1-, 2-, 3-year cumulative survival rates were used to evaluate the efficacy of the two operative procedures. Clinical stage (CS) was assessed retrospectively with the help of CT. The indications for extended radical operation were discussed.

RESULTS: There was no difference in hospital mortality and morbidity rates. Whereas the 1-, 2-, 3-year cumulative survival rates were 84.8%, 62.8%, 39.9% in the extended radical operation group, and were 70.8%, 47.6%, 17.2% in the Whipple operation group, there was a significant difference between the two groups (P<0.001, P<0.001, P<0.001, respectively). Most of the deaths within 3 years after operation were due to recurrence in the two groups. However, the 1-, 2-, 3-year cumulative rates of death due to local recurrence were decreased from 37.4% in patients that received the Whipple procedure to 23.8% in those who received by extended radical operation. Patients who survived for more than 3 years were only noted in those with CS1 in the Whipple procedure group and were founded in cases with CS1, CS2 and part of CS3 in the extended radical operation group.

CONCLUSION: The extended radical operation appears to benefit patients with pancreatic head carcinoma which was indicated in CS1, CS2 and part of CS3 without severe invasion.

- Citation: Mu DQ, Peng SY, Wang GF. Extended radical operation of pancreatic head cancer: Appraisal of its clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(16): 2467-2471

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i16/2467.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i16.2467

Although surgical resection is the only approach that can offer a possibility of cure for pancreatic cancer, however, the prognosis after curative resection continues to be the worst of the gastrointestinal neoplasms, there have been many controversies about whether extended radical resection is worthwhile or not compared with the Whipple procedure[1-3]. In the present study, an attempt was made to evaluate the effectiveness of extended radical operation in the treatment of pancreatic head cancer in comparison with the Whipple procedure and to discuss its indications.

A total of 56 patients with pancreatic head carcinoma were admitted to our Department from January 1995 to December 1998. Among them 39 were males and 17 females with an average age of 57.8 years (range 46-71 years). The patients did not receive any anticancer therapy before and after operation.

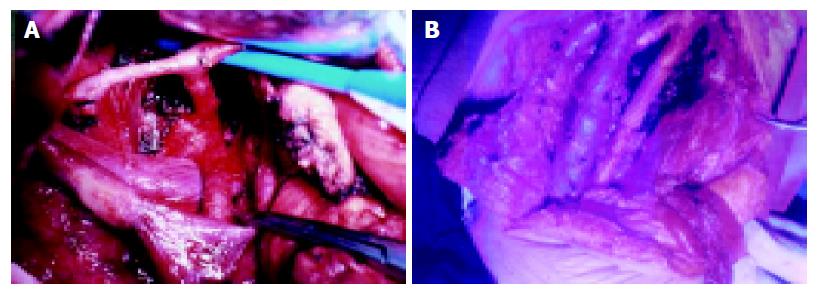

We performed the Whipple operation (Group I) and extended radical operation (Group II), respectively. In Group I, men/women were 2.2:1 with a median age of 57.3±4.6 years; in Group II men/women were 2.5:1 with a median age of 58.9±5 years. Lymphatic clearance in Group I was limited to that located directly adjacent to the pancreatic head. In the pancreas, the pancreatic resection line was on the left border of the superior mesenteric vein. In the subjects of Group II, the lymph node clearance was performed by dissection of N1 and N2 groups along with a proper clearance of N3 group and neighboring connective tissue clearance (Figures 1A and 1B). Among these nerve-plexuses resection around the retroperitoneum was conducted in 13 cases, resection and reconstruction of the portal-vein system were performed in 6 cases, and resection of the common hepatic artery or superior mesenteric artery was carried out in four patients. The resection line for pancreatic tissues was 1-2 cm from the left border of the aorta.

The clinical stage (CS) for all enrolled patients was assessed retrospectively by two independent and experienced examiners according to the maximal tumor size (T), retropancreatic invasion (Rp), portal-vein invasion (PV), and arterial (hepatic, celiac, or superior mesenteric artery) invasion from preoperative diagnostic images such as computed tomography (CT) scan and abdominal selective angiogram. Based on assessments of these four factors on a four-grade scale, the disease was classified in one of the four CS, using the following criteria: T1 0-2 cm, T2 2.1-4 cm, T3 4.1-6 cm,T4 >6 cm; Rp0 normal retropancreatic tissue on CT scan, Rp1 slight speculation in retropancreatic tissue, Rp2 limited invasion, Rp3 severe invasion; PV0 normal appearance of portal-vein, PV1 mild irregularity or rigidity of portal-vein, PV2 moderate irregularity of portal-vein, PV3 severe irregularity or stenosis of the portal-vein; A0 normal appearance of the major arteries, A1 mild displacement or rigidity of the major arteries, A2 moderate displacement or irregularity of the major arteries, A3 stenosis of a major artery.

The maximal size was verified postoperatively and accessed with the same staging method as that used in CT image staging. Retroperitoneal invasion was divided into ‘interstitial invasion’ and lymph node involvement, interstitial invasion includes lymphatic vessel, neural, and soft tissue invasion. Presence or absence of vascular invasion was recorded as ‘positive’ or ‘negative’. All findings of CT images were compared with pathological results. The resected specimens were in turn fixed in 40 g/L formaldehyde solution, sliced into 5 µm sections, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined with light microscope.

All patients were followed up postoperation and surveyed every 6 mo by systemic medical check-up including determinations of plasma carcinoembryonic antigen and CA19-9, ultrasonography and CT to make sure whether and where cancer recurrence developed. The tumor relapse was grossly classified as local, distant, or both according to the site of recurrence. Local recurrence was defined as a recurrent tumor mass within the tumor bed, while the distant recurrence was classified as hepatic metastasis and peritoneal dissemination.

The cumulative survival rate was calculated by a life table method. Statistical analysis was performed by using t and χ2 test. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Operative deaths were defined as those occurred within 30 d after operation. Hospital morbidity and mortality were 12.5% and 0% in group I and 14% and 0% in group II, respectively. There were no differences between the two groups. These data indicated that extended radical operation could be performed as safely as the Whipple procedure.

4, 28, 3, 0 cases in group I and 2, 6, 9, 4 cases in group II respectively belong to CS1, CS2. CS3, and CS4. The distribution of cases based on the following factors such as maximum tumor size, retropancreatic invasion, and enterohepatic vascular invasion see Table 1.

| Operativeprocedures (patients) | T | Rp | PV | A | ||||||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | Rp0 | Rp1 | Rp2 | Rp3 | PV0 | PV1 | PV2 | PV3 | A0 | A1 | A2 | A3 | |

| Whipple | 5 | 28 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 19 | 7 | 0 | 11 | 15 | 9 | 0 | 21 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Extended | 4 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 12 | 5 | 4 | 0 |

There was no significant difference in the distribution of in CS1(T1; Rp0; PV0, A0-1) and CS2(T1-2 Rp1 PV1 A0-1) between the two groups. However, more CS3(T2-3, Rp2 PV2 A2) and CS4(T3-4 Rp2-3 PV2-3 A2) patients had extended radical operation performed on them.

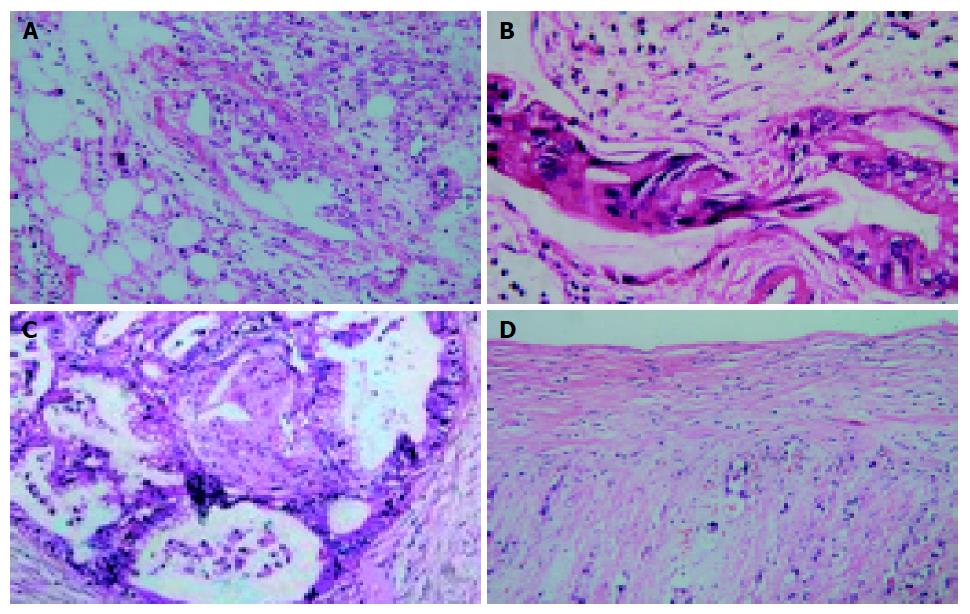

Tumor diameter ranged between 1.5 and 6.5 cm (mean 3.6 cm), in addition to pancreatic cancer coexisting with chronic pancreatitis (n = 3), pathological result were consensus with CT imaging. Histological assessment of Rp: negative pathological test for Rp0, Rp1 present with inflammatory adherence (n = 4) and microscopic metastasis in the form of tiny lymph nodes, lymphatics, and nerves invasion which were embedded in soft tissue (n = 22). Rp2 and Rp3 exhibited positive pathological outcomes. Rates of histologically proved metastasis to individual lymph nodes observed in our series were as follows: N1: N06: 23.8% (n = 5), N08: 14.4% (n = 3), N012inferior: 33.3% (n = 7), N013: 33.3% (n = 7), N014: 28.6% (n = 6), N017: 33.3% (n = 7), N2: N09: 14.4% (n = 3), N011: 19.1% (n = 4), N012superior:23.8% (n = 5), N016:23.8% (n = 5); N3: N03: 0%, N04: 0%, N05: 14.4% (n = 3), N07: 13.3% (n = 2). All metastatic lymph nodes present with the shape of big, middle, small as well as tiny nodus and themselves confluent types, metastatic frequency of lymph nodes was in turn tiny nodus (100%), small nodus (83%), middle nodus (79%), big nodus (66%). From the eight patients with PV2-3A2-3 that underwent vascular resection, correlation of CT findings with histopathological results was performed in 10 vessels (4SMVs, 2PVs, 3CHAs, 1SMAs). Histopathological invasion was found in 6 of 6 (100%) and 1 of 4 (25%) arteries. Figure 2 exhibited the histopathological results of CT findings present with T3Rp2PV2A2.

Comparisons of survival rate of two surgical treatments were made, the follow-up period was more than 3 years for all patients. In group I, six cases were lost and seven cases died of other diseases within 3 years. The remaining 22 cases died of cancer recurrence, 18 died within 3 years (13 patients died of local recurrence, five patients died of distant metastasis). In group II, two patients were lost and three patients died of other diseases within 3 years, the remaining 16 patients died of recurrence, nine patients died within 3 years (five patients died of local recurrence, another four patients died of distant metastasis). Comparison of the cumulative rate of survival between the two groups showed that the 1-, 2-, and 3-year cumulative survival rates were 70.8%, 47.6%, 17.2% in group I and 84.8%, 62.8%, 39.9% in group II, respectively. There was a significant difference between the two groups.

The ratio of the number of 3-year survivors to the number of patients in each clinical subgroup is shown in Table 2.

| Operative procedures(n) | T | Rp | PV | A | ||||||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | Rp0 | Rp1 | Rp2 | Rp3 | PV0 | PV1 | PV2 | PV3 | A0 | A1 | A2 | A3 | |

| Whipple | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Extended | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

The clinical tumor classification was compared between the two groups. A higher proportion of group I such as CS2 and CS3 died of local recurrence, but a significant difference is observed in CS3 (T2-3 Rp2 PV0-2 A0-1) in group II. The ratio of the number of local recurrence to the number of patients in each clinical subgroup is shown in Table 3.

| Operative procedures(n) | T | Rp | PV | A | ||||||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | Rp0 | Rp1 | Rp2 | Rp3 | PV0 | PV1 | PV2 | PV3 | A0 | A1 | A2 | A3 | |

| Whipple | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 8 | |||||

| Extended | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

The clinical tumor classification of patients who died of distant metastasis was compared between the two procedures. The ratio of the number of distant metastasis to the number of patients in each clinical subgroup is shown in Table 4.

| Operative procedure(n) | T | Rp | PV | A | ||||||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | Rp0 | Rp1 | Rp2 | Rp3 | PV0 | PV1 | PV2 | pV3 | A0 | A1 | A2 | A3 | |

| Whipple | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 5 | |||||

| Extended | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

Comparison of the cumulative rate of deaths due to total cancer recurrence between the two groups showed that 22 patients in group I and 9 patients in group II died of recurrence within 3 years after operation, the 3-year cumulative death rate was 51.4% in group I and 42.9% in group II. There was a significant difference between the two groups (P<0.05). Thirteen patients in group I and five patients in group II died of local recurrence, the 3 years cumulative death rate was 37.1% in group I and 23.8% in group II (P<0.05). Five patients in group I and four in group II died of distant metastasis, the 3 years cumulative death rate was 14.3% in group I and 19.0% in group II. These data showed that the extended radical operation could decrease deaths due to local recurrence, but could not reduce the death rate due to distant metastasis.

Finally, the cumulative survival rates were examined for their relations to CS as estimated retrospectively from preoperative assessments of images of the lesion by CT scan and abdominal selective angiography. As a result the cumulative survival rates (1-, 2- and 3-year) related to CS, were shown to be 100%, 71% and 57% for CS1; 71%, 47% and 26% for CS2; 46%, 12% and 7% for CS3; and 7%, 0% and 0% for CS4 patients. Thus 3-year survivors were noted to exist among CS1, CS2 and part of CS3 patients.

In this study, there were no differences in morbidity and mortality between patients performed by extended vs standard resection, but survival difference can be detected in patients with pancreatic cancer that underwent extended radical operation in comparison with those that underwent Whipple procedure. Although this was not a randomized trial and insignificant comparison of survival rate may be unreliable. Other prospective, randomized trials also have suggested that extended radical resection rather than the Whipple operation could provide survival advantages over patients with advanced pancreatic head cancer[4,5]. The reasons why extended lymphadenectomy should be performed are as follows. Lymph node studies conducted by us in the present study confirmed that patients who underwent the Whipple procedure have metastatic lymph nodes beyond the confines of the Whipple dissection. Pancreatic cancer cells had aggressively perineural invasion behaviors, even if there were no cancer cells at the margin of the pancreas at the time of surgery, the cancer cells may spread further to the noncancerous pancreas or retroperitoneum, where apparently provide a nidus for cancer recurrence after surgery[6,7]. A relationship between ‘interstitial invasion’ and lymph node metastases seems to exist. Nagai pointed out that the ‘interstitial invasion’ was almost invariably found in the regions where lymph node metastases were observed[8], Ishikawa further demonstrated that when metastatic lymph node was limited to the N1 region, due to ‘interstitial invasion’, microinvasion had already occurred in the N2 region[9]. Mao et al[10], stressed that spleenful lymphatic vessels in the retroperitoneal space might be a communicating channel, tumor cells not only spread from the N1 group to N2 group, but also bypass the N1 nodes to pass from the primary tumor to the N2 nodes via alternative routes, even if a metastasis was not found in the N1 nodes, N2 nodes were not necessarily free of tumor. Thus, the lymphatic vessels that are distributed throughout the capsule of the pancreas and the border between the pancreas and the retroperitonium act as routeways for tumor invasion into the peritoneal cavity. Many researchers deem that an extensive dissection of the retroperitoneum and extrapancreatic nerve pleux could lower local recurrence rate of pancreatic bed often involved by tumor extension[11-15]. Excision of regional blood vessels was usually precluded by the Whipple procedure, in the present study one patient with PV2(+) in group II could survive more than 3 years. Extended radical resection permitted elimination of potentially negative margins and sometimes long-term survival could be expected[16-18].

Extended radical resection required defined CS. In the present study, relation between evaluation of maximum of tumor, retroperitoneal invasion (Rp), arterial and venous invasion by CT imaging and histological correlation were performed. Tumor margin, in addition to a small number of pancreatic cancer coexisting with chronic pancreatitis, evaluation of the CT imaging were basically in accordance with pathological outcome. Retroperitoneal invasion in this study was divided into lymph node involvement and ‘interstitial invasion’. Types of metastatic lymph node included large nodus, middle nodus, small and tiny nodus and their integrated types. Tiny nodus were often embedded in fatty tissue and difficulty detected by CT imaging, however, the presence of such occult microscopic metastatic lymph node involvement was found in about 50% of patients with pancreatic cancer[19,20]. Presence of microscopic metastasis in occult lymph nodes, peripancreatic lymphatics, and nerves has been demonstrated in at least 50% of pancreatic cancers[21,22]. Such a phenomenon is indiscernible by CT imaging, only was divided into Rp1 in our present study. Evaluation of involved vessel system and pathological outcome were performed, we found differences between arterial and venous systems, cancer cells were proved to be aggressive against PV2 and PV3, however, as for A2 in CT imaging, only one patient with A2(+) confirmed the presence of cancer cells in the arterial wall. Nakayama et al[23], point out that the cause of artery stenosis or wall irregularity was due to fibrotic tissue prolifer-ation associated with tumor circumference, atherosclerotic changes of the artery wall, neointimal proliferation, or nontu-morous thrombus secondary to perivascular fibrotic changes in response to tumor growth.

Extended radical resection may be beneficial to selected patients. In this study, the extended radical operation resulted in a 3-year survival primarily for the patients with CS1, CS2 and part of CS3 (T2Rp2PV2A1). The incidence in 3-year survivors among patients with CS3 in the extended radical operation was found. None occurred in patients that underwent the Whipple procedure in the same clinical setting. The clinical evidence thus clearly indicated the therapeutic benefits of extended radical operation. The 3-year survival rate of patients has been improved by extended radical operation that decreased local recurrence. The rate of recurrence for patients with CS1 and CS2 lesions generally was lower than that for those with CS3 and CS4, i.e., extended radical operation was able to control local recurrence in patients with CS1, CS2 and CS3 (T2 Rp2PV2 A1) disease. However, radical resection was not an effective treatment for CS3 (T3Rp2PV2 A2) and CS4 (T3Rp3 PV3 A2-3) diseases. In the present study, CS3 was divided into CS3a(T2 Rp2PV2 A1) and CS3b(T3Rp2PV2 A1-2), because there exists abundant lymphatic vessels inside the pancreas which communicate with each other, as the tumor size enlarges, the chance of cancer cells invading lymphatic vessels and the rate of recurrence after resection increase. In Gebhardt’ series, when carcinoma measuring up to 2.1-4 cm, invasion of the lymphatic vessel in 81% of the patients, however carcinomas measuring 4.1-6 cm, invasion of the lymphatic vessel in 100% of the patients[24]. Ishikawa demonstrated that when tumors were larger than T2, even extended radical could control local recurrence, and distant metastasis could be avoided[9]. In addition to local recurrence, distant metastasis occurred commonly in CS3-4 (T3-4 Rp2-3 PV2-3 A2-3) in which we can see that patients with large tumors (T3-4), deeply retropancreatic invasion (Rp3), and enterohepatic vascular invasions (PV3, A2-3) were at a higher risk for death due to distant metastasis. Patients with Rp3, cancer cells either as single cells or cell clumps were randomly allocated to the large area of loose connective tissue of the peritonium[25], in such a condition extended radical resection has been proven to be unable to obtain negative margin, even the negative margin with a few millimeters away from the tumor was obtained, avoidance of future metastasis could not be assured[26]. It is suggested that patients with higher CSs such as CS3-4 (T3-4 Rp3 PV3A2-3) might have cancer extension beyond the limit of surgical management, even wide lymph node dissection, resection of surrounding connective tissue, and en bloc resection of major vessels could not obtain R0 surgery (without cancer cells). The negative survival impact of R1(residual tumor) surgery has been observed in many studies and was associated with high rates of local and regional recurrence[27]. Therefore, indicators of extended radical operation for pancreatic head cancer were CS1, CS2, and CS3 (T2Rp2PV2A1). It can be concluded that indication of extended radical operation is practically possible in CS1, CS2 and part of CS3 (T2-3Rp2PV2A1) but unrealistic in CS3-4(T3-4Rp2-3PV2-3A2-3).

Science Editor Wang XL Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Sasson AR, Hoffman JP, Ross EA, Kagan SA, Pingpank JF, Eisenberg BL. En bloc resection for locally advanced cancer of the pancreas: is it worthwhile? J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:147-157; discussion 157-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tsiotos GG, Farnell MB, Sarr MG. Are the results of pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer improving? World J Surg. 1999;23:913-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kawarada Y, Das BC, Naganuma T, Isaji S. Surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer. Does extended lymphadenectomy provide a better outcome? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:224-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pedrazzoli S, DiCarlo V, Dionigi R, Mosca F, Pederzoli P, Pasquali C, Klöppel G, Dhaene K, Michelassi F. Standard versus extended lymphadenectomy associated with pancreatoduodenectomy in the surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Lymphadenectomy Study Group. Ann Surg. 1998;228:508-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 570] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Popiela T, Kedra B, Sierzega M. Does extended lymphadenectomy improve survival of pancreatic cancer patients? Acta Chir Belg. 2002;102:78-82. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Hirai I, Kimura W, Ozawa K, Kudo S, Suto K, Kuzu H, Fuse A. Perineural invasion in pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2002;24:15-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Takahashi S, Hasebe T, Oda T, Sasaki S, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, Ueda T, Ochiai T, Ochiai A. Extra-tumor perineural invasion predicts postoperative development of peritoneal dissemination in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:1407-1412. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Nagai H, Kuroda A, Morioka Y. Lymphatic and local spread of T1 and T2 pancreatic cancer. A study of autopsy material. Ann Surg. 1986;204:65-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ishikawa O, Ohhigashi H, Sasaki Y, Kabuto T, Fukuda I, Furukawa H, Imaoka S, Iwanaga T. Practical usefulness of lymphatic and connective tissue clearance for the carcinoma of the pancreas head. Ann Surg. 1988;208:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mao C, Domenico DR, Kim K, Hanson DJ, Howard JM. Observations on the developmental patterns and the consequences of pancreatic exocrine adenocarcinoma. Findings of 154 autopsies. Arch Surg. 1995;130:125-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nagakawa T, Konishi I, Ueno K, Ohta T, Akiyama T, Kayahara M, Miyazaki I. Surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer. The Japanese experience. Int J Pancreatol. 1991;9:135-143. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Nagakawa T, Nagamori M, Futakami F, Tsukioka Y, Kayahara M, Ohta T, Ueno K, Miyazaki I. Results of extensive surgery for pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;77:640-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Imaizumi T, Hanyu F, Harada N, Hatori T, Fukuda A. Extended radical Whipple resection for cancer of the pancreatic head: operative procedure and results. Dig Surg. 1998;15:299-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nagakawa T, Konishi I, Ueno K, Ohta T, Kayahara M, Miyazaki I. Extended radical pancreatectomy for carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:849-854. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Ishikawa O, Ohigashi H, Yamada T, Sasaki Y, Imaoka S, Nakaizumi A, Uehara H, Tanaka S, Takenaka A. Radical resection for pancreatic cancer. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2002;65:166-170. [PubMed] |

| 16. | van Geenen RC, ten Kate FJ, de Wit LT, van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Segmental resection and wedge excision of the portal or superior mesenteric vein during pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery. 2001;129:158-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nakao A, Kaneko T, Takeda S, Inoue S, Harada A, Nomoto S, Ekmel T, Yamashita K, Hatsuno T. The role of extended radical operation for pancreatic cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:949-952. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Nakao A, Takeda S, Sakai M, Kaneko T, Inoue S, Sugimoto H, Kanazumi N. Extended radical resection versus standard resection for pancreatic cancer: the rationale for extended radical resection. Pancreas. 2004;28:289-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Edis AJ, Kiernan PD, Taylor WF. Attempted curative resection of ductal carcinoma of the pancreas: review of Mayo Clinic experience, 1951-1975. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55:531-536. [PubMed] |

| 20. | O'Brien PH, Mincey KH. Analysis of pancreatoduodenectomy. J Surg Oncol. 1985;28:50-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tsuchiya R, Noda T, Harada N, Miyamoto T, Tomioka T, Yamamoto K, Yamaguchi T, Izawa K, Tsunoda T, Yoshino R. Collective review of small carcinomas of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 1986;203:77-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tsuchiya R, Oribe T, Noda T. Size of the tumor and other factors influencing prognosis of carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:459-462. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Nakayama Y, Yamashita Y, Kadota M, Takahashi M, Kanemitsu K, Hiraoka T, Hirota M, Ogawa M, Takeya M. Vascular encasement by pancreatic cancer: correlation of CT findings with surgical and pathologic results. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25:337-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gebhardt C, Meyer W, Reichel M, Wünsch PH. Prognostic factors in the operative treatment of ductal pancreatic carcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2000;385:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hiraoka T, Uchino R, Kanemitsu K, Toyonaga M, Saitoh N, Nakamura I, Tashiro S, Miyauchi Y. Combination of intraoperative radiation with resection of cancer of the pancreas. Int J Pancreatol. 1990;7:201-207. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Kayahara M, Nagakawa T, Ueno K, Ohta T, Takeda T, Miyazaki I. An evaluation of radical resection for pancreatic cancer based on the mode of recurrence as determined by autopsy and diagnostic imaging. Cancer. 1993;72:2118-2123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Henne-Bruns D, Vogel I, Lüttges J, Klöppel G, Kremer B. Surgery for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head: staging, complications, and survival after regional versus extended lymphadenectomy. World J Surg. 2000;24:595-601; discussion 601-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |