Published online Apr 7, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i13.2009

Revised: November 26, 2004

Accepted: December 21, 2004

Published online: April 7, 2005

AIM: For patients of periampullary carcinoma found to be unresectable at the time of laparotomy, surgical palliation is the primary choice of treatment. Satisfactory palliation to maximize the quality of life with low morbidity and mortality is the gold standard for a good procedure. Our aim is to explore such a procedure as an alternative to the traditional ones.

METHODS: A modified double-bypass procedure is performed by, in addition to the usual gastrojejunostomy, implanting a mushroom catheter from the gall bladder into the jejunum through the interposed stomach as an internal drainage. A retrospective review was performed including 22 patients with incurable periampullary carcinomas who underwent this surgery.

RESULTS: Both jaundice and impaired liver function improved significantly after surgery. No postoperative deaths, cholangitis, gastrojejunal, biliary anastomotic leaks, recurrent jaundice or late gastric outlet obstruction occurred. Delayed gastric emptying occurred in two patients. The total surgical time was 150±26 min. The estimated blood loss was 160±25 mL. The mean length of hospital stay after surgery was 22±6 d. The mean survival was 8 mo (range 1.5-18 mo).

CONCLUSION: In patients of unresectable periampullary malignancies, stomach-interposed cholecystogastr-ojejunostomy is a safe, simple and efficient technique for palliation.

- Citation: Hao CY, Su XQ, Ji JF, Huang XF, Xing BC. Stomach-interposed cholecystogastrojejunostomy: A palliative approach for periampullary carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(13): 2009-2012

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i13/2009.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i13.2009

Malignant tumor of the periampullary region remains a disease with a grim prognosis. Despite great improvements in imaging and diagnostic techniques, the majority of patients with periampullary carcinoma are not resectable for potential cure at initial diagnosis. Therefore, the palliation of symptoms to maximize the quality of life remains an important primary component in the management of the disease. Palliation of patients with periampullary carcinoma is principally directed at three major symptoms: obstructive jaundice, duodenal/gastric outlet obstruction, and tumor-associated pain. Currently, both operative and nonoperative modalities are available to provide optimal palliation of symptoms. The management of most patients with periampullary carcinoma can be tailored to best suit the patients’ individual clinical presentation, overall medical condition, prognosis, and even economic status. Appropriate palliative surgical management is indicated in patients found to be unresectable at the time of laparotomy or those whose symptoms are not amenable to current nonoperative palliative techniques. Furthermore, operative palliation should also be considered in patients with high operative risks, even if technically the tumor might be resectable.

For those patients with duodenal obstruction at the time of presentation, surgical gastroenterotomy is currently the most commonly utilized option. For those with obstructive jaundice alone, the options for management must be weighed against factors such as the patient’s overall health status, projected survival, and the procedure-related morbidity and mortality. Beginning in 1997, we adopted a modified double-bypass as palliative modality in the periampullary cancer patients who were not qualified for curative resection and the life expectancy of whom were less than one year. This surgery, which we call “stomach-interposed cholecystogastr-ojejunostomy” is simple in manipulation, takes little time, does not increase the operative morbidity or mortality, and improves the overall well-being of patients.

Clinical records of 22 patients with unresectable periampullary malignancies who underwent stomach-interposed cholecyst-ogastrojejunostomy between June 1997 and February 2004 in Beijing Cancer Hospital were retrospectively reviewed. Seventeen patients were men. The mean age was 63 years (range 52-76 years). The diagnosis of periampullary malignancies included lesions in the head of the pancreas, ampulla of Vater, distal bile duct and duodenum. Diagnosis was made based on the preoperative radiologic and/or endoscopic studies, as well as intraoperative findings. Not all were histologically confirmed. Follow-up information was completed through July 2004 on all patients based on direct patients contact, contact with their families or hospital records. Survival information was available for all 22 patients. In this series, no ne of the patients had abdominal/back pain or radiographic evidence of duodenal obstruction before surgery. Obstructive jaundice was found in all patients. Elevated levels of serum transaminases (SGPT and SGOT) were found in 15 patients. Based on the preoperative evaluation and surgical findings, 16 patients were thought to have tumors arising in the head of pancreas. The most common reason for unresectability at the time of laparotomy was local invasion or liver and peritoneal metastasis, which were present in 14 and 6 patients, respectively.

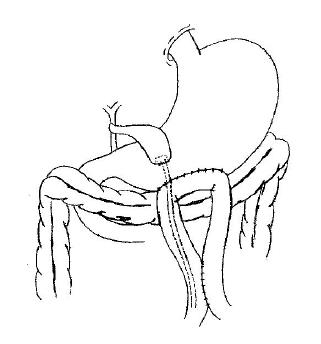

After the peritoneal cavity has been explored and the tumor is determined to be unresectable, the patency of the cystic duct and its relationship to the tumor are assessed to make sure that the cystic duct is patent and will remain so for a reasonable length of time. The assessment could be made directly by dissecting the cystic duct and the common bile duct, or by intraoperative cholangiography. Place a circular purse-string suture of 1.5 cm diameter on the fundus of the gall bladder, make a stab wound in the center of the purse-string suture with the electrocautery and insert a mushroom catheter of appropriate size (20-22 F) into the gall bladder. The purse-string suture is then tied snugly around the catheter. Another purse-string suture is made on the anterior wall of the stomach, a second stab wound is created in the center of it and the catheter is passed into the stomach. The suture is then tightened. To complete the cholecystogastrostomy, the seromuscular layer of the stomach is approximated to the fundus of the gall bladder with interrupted sutures of 3-0 silk close to the purse-string suture. An antecolic side-to-side gastrojejunostomy is made on the great curvature of the most dependent portion of the stomach. A Braun jejunojejunostomy is performed between the afferent and efferent loops of the jejunum. Therefore, it is important that the afferent loop should not be too short. The mushroom catheter is then introduced into the efferent loop through the gastrojejunostomy, leaving its opposite end below the enteroanastomosis. The abdomen is closed without drains. All procedures are demonstrated in Figure 1.

According to the general principles of surgical and supportive care, the standard postoperative treatment included hemodynamic monitoring with a central venous catheter, urinary catheter, fluid balance and adequate replacement of electrolytes. The nasogastric tube was removed when flatus has been expelled. Perioperative parenteral antibiotics were administered to all patients, and postoperative epidural analgesics were administered as needed. Patients were given nothing by mouth for the first 48 h after surgery. Some of the patients received early parenteral nutrition through a feeding jejunostomy tube. Follow-up after discharge was done every month for the first 6 mo, and then as needed based on the condition of patients.

A remarkable alleviation of jaundice was seen in all patients, and improvements in serum transaminase levels were noticed in all who had elevated liver enzymes before surgery. No postoperative hospital deaths or deaths within the first 30 d occurred after surgery. No postoperative cholangitis occurred. Delayed gastric emptying, defined as 10 d or more of nasogastric suction or persistent vomiting requiring reinsertion of the nasogastric tube, was found in five patients. Both responded to a period of nasogastric suction. There were no cases of postoperative gastrojejunal or biliary anastomotic leaks. None of the patients developed recurrent jaundice.

The total surgical time was 150±26 min. The estimated blood loss was 160±25 mL. The mean length of hospital stay after surgery was 22±6 d. The median survival of the group was 8 mo (range 1.5 to 18 mo), no catheter-related problems occurred in any patients. Three patients reported back pain at the time of the 4th, 6th and 9th month after operation respectively, all were controlled very well by celiac axis block guided by ultrasound. During the follow-up period, none of the patients developed late gastric outlet obstruction before death.

Although great improvement has been achieved in surgical as well as nonoperative techniques, the overall prognosis for patients with periampullary malignancies remains poor. Palliation of symptoms remains a cornerstone of therapy for these patients. The goal of palliation therapy lies in two points, i.e., to prolong life by relieving life threatening biliary and/or duodenum obstruction and to improve the quality of life by eliminating intractable pruritus associated with jaundice, persistent nausea and vomiting due to duodenal obstruction, and also intractable pain related to the extensive tumor involvement of the celiac nerves. Due to the limited survival time of these patients and their susceptibility to major postoperative complications, the operative procedure should provide maximum benefit with minimal risk of complications.

Significant advances have been made in nonoperative palliation of periampullary cancer in recent years[1-6]. Percutaneous and endoscopic palliation of obstructive jaundice can provide biliary tract decompression with lower early morbidity than open biliary bypass[3,5,7]. Metallic expandable stents can now be used to palliate the obstruction of either the bile duct or the duodenum[3,4,8,9]. Many reports have described the laparoscopic techniques for bypass of the obstructed duodenum and/or biliary tract[2,8,10]. However, laparotomy performed for determination of resectability also offers the opportunity to provide long-term palliation of biliary obstruction, duodenal obstruction and intractable pain. The long term success of palliation was confirmed in our series.

There is still a controversy surrounding performing the double-bypass in patients without gastric outlet obstruction[11-13]. However, more and more reports support the prophylactic measures for potential gastric outlet obstruction in the future[14-17]. Although the number of patients in our series is not statistically large, it confirms that if both the surgical procedure and the patients are properly selected, satisfactory palliation can be achieved without sacrificing increases in morbidity and mortality.

Usually, the gall bladder cannot be anastomosed with the stomach directly, due to heavy alkaline erosive gastritis and cholecystitis shortly after the surgery. Both of which can be lethally severe. Traditionally, a combined biliary bypass and gastrojejunostomy through a Roux-en-Y limb is constructed for palliation of inoperable periampullary cancer patients. This procedure usually takes about 4.6 h with the mean estimated introoperative blood loss of 300 mL[18].

Use of the gall bladder for biliary decompression in periampullary malignancies, there is concern that the primary malignant neoplasm relentlessly creeps upward, by direct extension, along and around the common bile duct to obstruct the gastric duct. Sarfeh et al, reported that choledochoenterotomy is a significantly more effective method of palliation than the use of gall bladder and should be the procedure of choice. In the 31 randomized patients, seven bypass failed after the use of gall bladder, while only two failed using the bile duct (P<0.04). Prior to death, 47% of cholecystojejunostomies failed[19]. On the basis of these data, many authors have preferred the routine use of the common bile duct for palliative biliary drainage. Unfortunately, in all these reports, no uniform evaluation of cystic duct patency was obtained and no explanation was offered regarding the selection of patients or choice of biliary drainage. When gall bladder is considered in biliary decompression, the most important factors in determining the drainage result are the level of entry of the cystic duct and its relationship to the obstructing tumor. Although the cystic duct may be patent at the time of surgery, there is a risk of occlusion by advancing tumor and early recurrent jaundice. It is therefore prudent to demonstrate not only patency of the cystic duct but also an adequate distance between its point of entry and the level of obstruction before embarking upon the procedure. No clear guidelines exist for the safe distance between the entry of cystic duct and the tumor, but a 2-3 cm gap seems reasonable[20]. If the cystic duct is not patent or entry is close to the neoplasm, the common bile duct should be used for decompression and the technique described in this article is not feasible. In evaluating over than 60 published series, Sarr and Cameron did not find any clear advantage of choledochojejunostomy over cholecystojejunostomy[21]. It is likely that the injudicious use of the gall bladder is largely responsible for the poor results of cholecystojejunostomy. Nevertheless, our series showed that the use of gall bladder for palliative biliary drainage is easy to access, quicker to perform, associated with less blood loss and satisfactory palliation, provided that the cystic duct patency has been properly demonstrated. However, when prolonged survival is anticipated, common bile duct drainage is preferable.

This original technique of double-bypass actually has only two true anastomoses, i.e., a gastrojejunostomy and a jejunojejunostomy. Bile is drained into the jejunum through an internally implanted mushroom catheter, which simplifies the usually high skill-requiring, time-consuming, and leak-risk bilioenterostomy into a catheter implantation procedure. This modality greatly decreases the occurrence of postoperative cholangitis, and should also reduce the chance of bile leak. On the other hand, the risks of stomal ulceration and the bile reflux are also lowered. A further merit of the procedure is that no Roux-en-Y limb is required, so no mesenteric dissection is needed. This will greatly shorten the surgery time, decrease the chance of bleeding, as well as reduce postoperative complications. All of which will be of significant benefits for the postoperative recovery process.

Traditionally, gastrojejunal anastomoses have been placed on the posterior wall of the stomach to improve drainage. However, posterior drainage is dependent drainage only when the patient is lying flat in bed on his or her back. It is questionable whether the average patient spends enough hours in this position to warrant the additional difficulty and time of placing the gastrojejunostomy in a posterior location, especially when the patient is at high operative risk. On the other hand, a posterior gastrojejunostomy increases the possibility of subsequent infiltration by tumor. Therefore we prefer to perform an anterior gastrojejunostomy along the great curvature of the antrum located not more than 5-7 cm from the pylorus. The reasons for the construction of the Braun enteroanastomosis include prevention of the afferent loop syndrome, and minimization of bile reflux to the stomach.

We do not routinely perform chemical splanchnicectomy in patients without preoperative complaint at the time of laparotomy. This procedure takes time, demands further dissection, and more importantly, the effects of chemical splanchnicectomy are usually not permanent[22]. Most patients who develop postoperative abdominal/back pain respond well to percutaneous celiac axis blocks under the guidance of ultrasound or CT[23].

In conclusion, for patients with unresectable periampullary malignancies, stomach-interposed cholecystogastrojejunostomy is a safe, simple and efficient technique with satisfactory palliation.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Schwarz A, Beger HG. Biliary and gastric bypass or stenting in nonresectable periampullary cancer: analysis on the basis of controlled trials. Int J Pancreatol. 2000;27:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Holzman MD, Reintgen KL, Tyler DS, Pappas TN. The role of laparoscopy in the management of suspected pancreatic and periampullary malignancies. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:236-243; discussion 243-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van den Bosch RP, van der Schelling GP, Klinkenbijl JH, Mulder PG, van Blankenstein M, Jeekel J. Guidelines for the application of surgery and endoprostheses in the palliation of obstructive jaundice in advanced cancer of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 1994;219:18-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cheng JL, Bruno MJ, Bergman JJ, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Endoscopic palliation of patients with biliary obstruction caused by nonresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma: efficacy of self-expandable metallic Wallstents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:33-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ferlitsch A, Oesterreicher C, Dumonceau JM, Deviere J, Leban T, Born P, Rösch T, Suter W, Binek J, Meyenberger C. Diamond stents for palliation of malignant bile duct obstruction: a prospective multicenter evaluation. Endoscopy. 2001;33:645-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zoepf T, Jakobs R, Arnold JC, Apel D, Rosenbaum A, Riemann JF. Photodynamic therapy for palliation of nonresectable bile duct cancer--preliminary results with a new diode laser system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2093-2097. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Andersen JR, Sørensen SM, Kruse A, Rokkjaer M, Matzen P. Randomised trial of endoscopic endoprosthesis versus operative bypass in malignant obstructive jaundice. Gut. 1989;30:1132-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 436] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Arguedas MR, Heudebert GH, Stinnett AA, Wilcox CM. Biliary stents in malignant obstructive jaundice due to pancreatic carcinoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:898-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Spitz JD, Arregui ME. Endoscopic palliation for pancreatic cancer with expandable metal stents. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:502. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Bruha R, Petrtyl J, Kubecova M, Marecek Z, Dufek V, Urbanek P, Kodadova J, Chodounsky Z. Intraluminal brachytherapy and selfexpandable stents in nonresectable biliary malignancies--the question of long-term palliation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:631-637. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Jacobs PP, van der Sluis RF, Wobbes T. Role of gastroenterostomy in the palliative surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1989;42:145-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Weaver DW, Wiencek RG, Bouwman DL, Walt AJ. Gastrojejunostomy: is it helpful for patients with pancreatic cancer? Surgery. 1987;102:608-613. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Egrari S, O'Connell TX. Role of prophylactic gastroenterostomy for unresectable pancreatic carcinoma. Am Surg. 1995;61:862-864. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Hardacre JM, Sohn TA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Is prophylactic gastrojejunostomy indicated for unresectable periampullary cancer? A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1999;230:322-328; discussion 328-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shyr YM, Su CH, Wu CW, Lui WY. Prospective study of gastric outlet obstruction in unresectable periampullary adenocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2000;24:60-64; discussion 64-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | van Heek NT, van Geenen RC, Busch OR, Gouma DJ. Palliative treatment in "peri"-pancreatic carcinoma: stenting or surgical therapy? Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2002;65:171-175. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Van Heek NT, De Castro SM, van Eijck CH, van Geenen RC, Hesselink EJ, Breslau PJ, Tran TC, Kazemier G, Visser MR, Busch OR. The need for a prophylactic gastrojejunostomy for unresectable periampullary cancer: a prospective randomized multicenter trial with special focus on assessment of quality of life. Ann Surg. 2003;238:894-902; discussion 902-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Huang JJ, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Surgical palliation of unresectable periampullary adenocarcinoma in the 1990s. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:658-666; discussion 666-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sarfeh IJ, Rypins EB, Jakowatz JG, Juler GL. A prospective, randomized clinical investigation of cholecystoenterostomy and choledochoenterostomy. Am J Surg. 1988;155:411-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Singh SM, Reber HA. Surgical palliation for pancreatic cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 1989;69:599-611. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Sarr MG, Cameron JL. Surgical palliation of unresectable carcinoma of the pancreas. World J Surg. 1984;8:906-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Kaufman HS, Yeo CJ, Pitt HA, Sauter PK. Chemical splanchnicectomy in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1993;217:447-455; discussion 456-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen M, Hao C, Zhang H. Analgesic effect of neurolytic celiac plexus block guided by ultrasonography in advanced malignancies. Zhonghua YiXue ZaZhi. 2001;81:418-421. [PubMed] |