Published online Mar 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1798

Revised: May 27, 2004

Accepted: June 25, 2004

Published online: March 28, 2005

AIM: Patients with chronic hepatitis C have been recommended to receive vaccinations against hepatitis B. Our study aimed at evaluating the hepatitis B immunogenicity and efficacy against hepatitis B virus infection 4 years after primary immunization series in a group of patients with chronic hepatitis C.

METHODS: We recruited 36 out of 48 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infected individuals who were vaccinated against hepatitis B virus (20 μg of recombinant HBsAg at 0-1-6 mo schedule) in 1998. Here we measured anti-HBs titers and anti-HBc 4 years after delivery of the third dose of primary immunization series.

RESULTS: After 4 years a total of 13/36 (36%) HCV infected patients had seroprotective titers of anti-HBs compared with 9/10 (90%) in the control group, (P<0.05). Similarly the mean concentration of anti-HBs found in hepatitis C patients was significantly lower than that found in healthy subjects (18.3 and 156.0 mIU/mL respectively (P<0.05). None of the HCV infected patients or controls became infected with HBV during the study period as confirmed by anti-HBc negativity.

CONCLUSION: We demonstrated that 4 years after HBV immunizations’ more than 60% of vaccinated HCV patients did not maintain seroprotective levels of anti-HBs, which might put them at risk of clinically significant breakthrough infections. Further follow-up studies are required to clarify whether memory B and T lymphocytes can provide protection in chronic hepatitis C patients in the absence or inadequate titers of anti-HBs.

- Citation: Chlabicz S, Lapinski TW, Grzeszczuk A, Prokopowicz D. Four-year follow up of hepatitis C patients vaccinated against hepatitis B virus. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(12): 1798-1801

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i12/1798.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1798

Patients with chronic hepatitis C have been recommended to receive vaccinations against hepatitis B[1,2]. The rationale behind these recommendations is based on the fact that hepatitis C patients co-infected with hepatitis B virus have an increased histological liver damage and a higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma[3]. Additionally HCV patients may be at a higher than an average risk of acquiring hepatitis B because of the similar routes of transmission of both viruses. Several studies have shown that certain groups like intravenous drug users, haemodialysis patients, haemophiliacs, and promiscuous people frequently have markers of both infections. In a cross-sectional study of general population in the United States of America, more than 25% of HCV patients had also hepatitis B markers - which was nearly six times higher than in the HCV-negative group[4].

Previous studies demonstrated the safety of HBV vaccine use in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Immunisations did not aggravate the course of hepatitis C and had no effect on serum HCV-RNA levels[5-7]. Our earlier study proved that vaccinations could be safely delivered during treatment with interferon[5].

Studies of the hepatitis B vaccine immunogenicity in patients with hepatitis C have yielded mixed results. Most of them (but not all) indicated a diminished response to HBV vaccine delivered in a standard dose and schedule[5-8]. In our own experience, the HBV vaccine immunogenicity in patients with hepatitis C was decreased. One month after the final vaccine dose (Engerix B 20 μg), the overall seroprotection rate in 48 hepatitis C hepatitis was 72.9%, compared to 90.9% in the healthy controls (P<0.05)[5,8]. Similar results were obtained recently by Leroy[9] in a study of HBV vaccine immunogenicity (20 μg) delivered in a 0-1-2- mo schedule. The seroprotection rate was 63.6% in 77 HCV infected patients and 93.9% in 231 controls. It is currently not known how long the duration of the immunity lasts and whether patients with hepatitis C should be tested for anti-HBs and revaccinated if anti-HBs falls below 10 mIU/mL. The data are limited because no long-term studies have been published.

Our study aimed at evaluating the hepatitis B immunogenicity and efficacy against hepatitis B virus infection 4 years after primary immunization series in a group of patients with chronic hepatitis C.

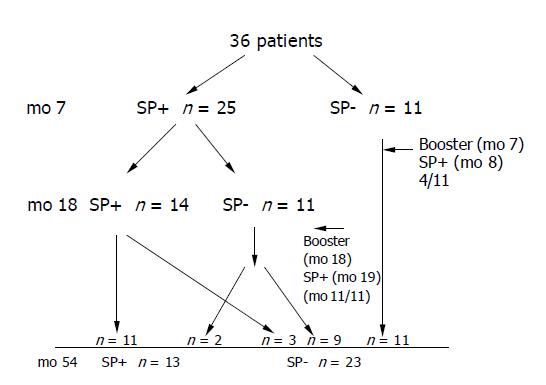

In 1998, 48 patients with chronic hepatitis C were vaccinated against hepatitis B in a standard 0-1-6 - mo schedule (20 μg Engerix B, SmithKline Beecham Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium). All patients visiting the Department of Infectious Diseases at the Medical University of Bialystok between July 1998 and April 1999 were invited to participate in the study. The patients and methods were described in our previous report[5]. Here we recruited 36 out of 48 individuals who participated in our previous vaccination trial to evaluate the immunogenicity and safety of hepatitis B vaccine in patients with chronic hepatitis C. At the entry to the study the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis C was based on the presence of anti-HCV, HCV-RNA and elevated alanine aminotransferase activity. Liver histopathology was available in 35/48 cases and all histologies were consistent with chronic hepatitis. None of the patients was cirrhotic. Patients with clinical evidence of liver decompensation, history of intravenous drug use, history of haemodialysis or with HIV infection were excluded. Patients receiving antiviral treatment during the study period were eligible to participate (interferon alone or in combination with ribavirin). Anti-HCV antibodies were assayed by the third-generation ELISA, (IMx MEIA, Abbott, Chicago, USA) and serum HCV RNA testing was performed using RT-PCR method. All patients were anti-HBc and anti-HBs negative prior to hepatitis B immunisations in 1998/1999. The participants were tested for anti-HBs one month after the third vaccine dose (mo 7) and 12 mo later (mo 18). Subjects who had an anti-HBs titer below 10 mIU/mL at month 7 or 18 were offered a single booster of 20 μg of recombinant HBV vaccine (Figure 1). Here we measured anti-HBs titers and anti-HBc 4 years after delivery of the third dose of primary immunization series. The original control group consisted of 11 healthy subjects of whom 10 agreed to participate in the present study.

Anti-HBs titers were measured with anti-HBs total test (EIA, BioMeri ux, Marcy-l’Etolle, France). The seroprotection was defined as anti-HBs level ≥10 mIU/mL. The efficacy of the vaccine was measured by the rate of infection with HBV. For the purpose of this study, HBV infection was defined as appearance of anti-HBc antibodies in a previously negative individual. The highest anti-HBV titer assayed was 500-mIU/mL and such maximal titers were used for calculating geometric mean titer (GMT). Testing for anti-HBc was performed with anti-HBc total test (EIA, BioMerieux, Marcy-l’Etolle, France). Statistical analysis was performed with the use of statistical software package Statistical PL. The differences between groups were determined by pairwise comparisons using χ2 test (with Yates’ correction when necessary) for seroprotection rates and two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test for anti-HBs; P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The study and consent procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee at the Medical University of Bialystok.

All the 48 patients with chronic hepatitis C were sent information about the follow-up tests and 36 were available and agreed to participate in the study. The present study analyzed the responses to HBV immunisations in those 36 individuals. Among the 12 lost hepatitis C individuals there were 8 persons with anti-HBs ≥100 one month after the third vaccine dose, 2 with anti-HBs 10-99 mIU/mL and 2 had anti-HBs<10 mIU/mL. The one lost individual in the control group was a good responder (anti-HBs ≥100 mIU/mL).

The characteristics of the study and control groups are presented in Table 1. Figure 1 provides details of the follow-up with the number of patients achieving seroprotective levels of anti-HBs at months 7, 18 and 54. Single boosters were given to 11 non-responders at mo 7 (4 achieved seroprotection). The eleven participants had anti-HBs ≥10 mIU/mL at mo 7 but were found unprotected at month 18. All those patients were given a single booster, which led to seroprotection in all cases one month later (Figure 1).

| Hepatitis C | Control group | |

| Number of patients | n = 36 | n = 10 |

| Mean age in yr (range) | 46.0 (22-78) | 40.4 (22-65) |

| Gender ratio (F/M) | 12/36 33.3/66.7% | 4/10 40%/60% |

| BMI (SEM) | 25.4 | 23.5 |

A total of 13/36 (36%) HCV infected patients had seroprotective titers of anti-HBs after 4 years compared with 9/10 (90%) in the control group (P<0.05). The only patient without seroprotection in the control group was a non-responder to primary vaccination series. Similarly the mean concentration of anti-HBs found in hepatitis C patients was significantly lower than that found in healthy subjects (18.3 and 156.0 mIU/mL respectively, P<0.05).

The seroprotection after 4 years in HCV infected patients was related to their response to primary series. Only 3/20 patients (15%) with anti-HBs at mo 7 less than 100 mIU/mL had seroprotective titers 4 years later despite the fact that 19/20 subjects were given boosters because of anti-HBs<10 mIU/mL either at month 7 or 18. Of the remaining 16 persons with anti-HBs ≥100 mIU/mL at mo 7 (good responders), 10 (62.5%) were seroprotected 4 years later (P<0.05).

None of the HCV infected patients or controls became infected with HBV during the study period as reflected by anti-HBc negativity.

This is the first long-term study evaluating the immunogenicity and efficacy of HBV vaccine in patients with chronic hepatitis C. We demonstrated that majority of the patients with hepatitis C were not seroprotected against HBV infection four years after primary immunization series. At the same time however, none of our vaccinees became infected with HBV. In immunocompetent hosts, maintaining anti-HBs levels ≥10 mIU/mL were not essential for protection against clinically significant breakthrough HBV infection (with HBsAg seropositivity and clinical manifestations of the disease)[10]. Primary exposure to HBsAg could lead to clonal proliferation of memory B lymphocytes. Memory B and T cells could retain the capacity to induce the production of antibodies upon re-exposure to HBsAg. Thus the pool of memory lymphocytes could confer long-term protection even when antibodies were absent[11]. The anti-HBs level of ≥10 mIU/mL after the primary vaccination series has been adopted as an indicator of immunological priming of B lymphocytes. Current recommendations require no boosters for those immunocompetent vaccines who were immunologically primed after the primary series[10]. In our study 7/36 (19.4%) patients were not primed despite a booster dose delivered at mo 7. Only 4 of the 11 (36,4%) nonresponders to primary series achieved seroprotection after the fourth dose of vaccination at mo 7. Most reports in medical literature indicate a more favourable (40-100%) response to a single hepatitis B vaccine booster in healthy nonresponders[12,13].

Regular testing for anti-HBs and administering boosters if anti-HBs falls below 10 mIU/mL is advisable for immunocompromised patients like those on haemodialysis[14]. Priming the immunological response could not guarantee a long term immunity in this group. Clinically significant infections have been documented in dialysis subjects who subsequently lost protective levels of antibodies after having a previously established immune response to HBV vaccinations[15]. Our study suggested that immunologic memory was present in those individuals with HCV infection who responded to the primary vaccination series. This was reflected by the fact that all the 11 individuals who lost seroprotective titers of anti-HBs between months 7 and 18 responded to a booster. However the responses were rather low and short-lived, only 2/11 subjects maintained the anti-HBs level ≥10 mIU/mL 3 years later.

It seems that HCV infected patients fall to the immunocompromised category of individuals. In our study this was reflected by the significantly lower anti-HBs levels in hepatitis C group when compared with immunocompetent individuals from the control group (483.6 mIU/mL in HCV patients vs 145.7 mIU/mL in healthy subjects at mo 7 and 156 mIU/mL vs 18.3 mIU/mL at mo 54 in both groups respectively). An impairment in both humoral and cellular responses could explain the low responses to HBV immunisations in HCV patients[16].

We observed no HBV infection in HCV infected patients irrespectively of anti-HBs levels. This, however, could not prove immunity. The small population size and the short duration of observation could not determine the efficacy. Probably only one patient was exposed to HBsAg which resulted in anamnestic response and increase in anti-HBs titers. In the remaining 35 HCV infected patients the levels of antibodies decreased, confirming the lack of HBsAg challenges.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that 4 years after HBV immunisations more than 60% of vaccinated HCV infected patients could not maintain seroprotective levels of anti-HBs, which might put them at risk of clinically significant breakthrough infections. Even if we considered that the 8 lost individuals who were good responders at mo 7 were seroprotected at mo 54, 52.3% (23/44) would still not be protected.

Further follow-up studies are required to clarify whether memory B and T lymphocytes can provide protection in chronic hepatitis C patients in the absence or inadequate titers of anti-HBs and if not an annual monitoring of anti-HBs should be offered and boosters to those with anti-HBs titer less than 10 mIU/mL. Before the results of larger studies with a longer follow up are available, it would be interesting to measure immunologic memory by means of observing anti-HBs responses after booster administration as well as assessing in vitro responses of T cells to HbsAg and B cells to stimulation by a B-cell spot ELISA[17].

Science Editor Wang XL Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | NIH consensus development conference targets prevention and management of hepatitis C. Am Fam Physician. 1997;56:959-961. [PubMed] |

| 2. | EASL International Consensus Conference on hepatitis C. Paris, 26-27 February 1999. Consensus statement. J Hepatol. 1999;31 Suppl 1:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Marusawa H, Osaki Y, Kimura T, Ito K, Yamashita Y, Eguchi T, Kudo M, Yamamoto Y, Kojima H, Seno H. High prevalence of anti-hepatitis B virus serological markers in patients with hepatitis C virus related chronic liver disease in Japan. Gut. 1999;45:284-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F, Moyer LA, Kaslow RA, Margolis HS. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:556-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1934] [Cited by in RCA: 1900] [Article Influence: 73.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chlabicz S, Grzeszczuk A, Łapiński TW. Hepatitis B vaccine immunogenicity in patients with chronic HCV infection at one year follow-up: the effect of interferon-alpha therapy. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8:CR379-CR383. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lee SD, Chan CY, Yu MI, Lu RH, Chang FY, Lo KJ. Hepatitis B vaccination in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 1999;59:463-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wiedmann M, Liebert UG, Oesen U, Porst H, Wiese M, Schroeder S, Halm U, Mössner J, Berr F. Decreased immunogenicity of recombinant hepatitis B vaccine in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2000;31:230-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chlabicz S, Grzeszczuk A. Hepatitis B virus vaccine for patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Infection. 2000;28:341-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Leroy V, Bourliere M, Durand M, Abergel A, Tran A, Baud M, Botta-Fridlund D, Gerolami A, Ouzan D, Halfon P. The antibody response to hepatitis B virus vaccination is negatively influenced by the hepatitis C virus viral load in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a case-control study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:485-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Are booster immunisations needed for lifelong hepatitis B immunity? European Consensus Group on Hepatitis B Immunity. Lancet. 2000;355:561-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Leroux-Roels G, Van Hecke E, Michielsen W, Voet P, Hauser P, Pêtre J. Correlation between in vivo humoral and in vitro cellular immune responses following immunization with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) vaccines. Vaccine. 1994;12:812-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Das K, Gupta RK, Kumar V, Kar P. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of a recombinant hepatitis B vaccine in subjects over age of forty years and response of a booster dose among nonresponders. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1132-1134. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Wismans P, van Hattum J, Stelling T, Poel J, de Gast GC. Effect of supplementary vaccination in healthy non-responders to hepatitis B vaccination. Hepatogastroenterology. 1988;35:78-79. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Hepatitis B virus: a comprehensive strategy for eliminating transmission in the United States through universal childhood vaccination. Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 1991;40:1-25. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Stevens CE, Alter HJ, Taylor PE, Zang EA, Harley EJ, Szmuness W. Hepatitis B vaccine in patients receiving hemodialysis. Immunogenicity and efficacy. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:496-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 307] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Idilman R, De MN, Colantoni A, Nadir A, Van Thiel DH. The effect of high dose and short interval HBV vaccination in individuals with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wismans PJ, van Hattum J, De Gast GC, Endeman HJ, Poel J, Stolk B, Maikoe T, Mudde GC. The spot-ELISA: a sensitive in vitro method to study the immune response to hepatitis B surface antigen. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;78:75-79. [PubMed] |