Published online Mar 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1769

Revised: August 21, 2004

Accepted: October 18, 2004

Published online: March 28, 2005

AIM: To assess systematically the spectrum and extent of depressive symptoms comparing patient groups receiving peginterferon or conventional interferon.

METHODS: Ninety-eight patients with chronic hepatitis C and interferon-based therapy (+ribavirin) were consecutively enrolled in a longitudinal study. Patients were treated with conventional interferon alfa-2b (48/98 patients; 5 MIU interferon alfa-2b thrice weekly) or peginterferon alfa-2b (50/98 patients; 80-150 μg peginterferon alfa-2b) in combination with weight-adapted ribavirin (800-1200 mg/d). Repeated psychometric testing was performed before, three times during and once after antiviral therapy: Depression was evaluated by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), anger/hostility by the Symptom Checklist-90 Items Revised (SCL-90-R).

RESULTS: Therapy with pegylated interferon alfa-2b produces comparable scores for depression (ANOVA: P = 0.875) as compared to conventional interferon. Maximums of depression scores were even higher and cases of clinically relevant depression were frequent during therapy with peginterferon. Scores for anger/hostility were comparable for both therapy subgroups.

CONCLUSION: Our findings suggest that the extent and frequency of depressive symptoms in total are not reduced by peginterferon. Monitoring and management of neuropsychiatric toxicity especially depression have to be considered as much as in antiviral therapy with unmodified interferon.

- Citation: Kraus MR, Schäfer A, Csef H, Scheurlen M. Psychiatric side effects of pegylated interferon alfa-2b as compared to conventional interferon alfa-2b in patients with chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(12): 1769-1774

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i12/1769.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1769

Chronic hepatitis C is one of the most frequent chronic infectious diseases worldwide with a global prevalence of 1-2%[1]. It has been estimated that approximately 170 million people are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV)[2-5]. Chronic disease occurs in approximately 85% of patients following HCV infection. Of these patients, up to 20% develop liver cirrhosis[1,4-6]. The goal of antiviral treatment in chronic hepatitis C is sustained virological response, which is achieved at present (combination therapy with peginterferon and ribavirin) in more than 50% of patients[7,8]. However, medical treatment for hepatitis C is still unsatisfactory because it is expensive and often poorly tolerated. An additional problem is the high prevalence of relevant depression and anxiety[9] found even in untreated patients with chronic hepatitis C. These symptoms may be aggravated to a serious degree by interferon alfa therapy[10-14].

Peginterferon was announced and introduced to be at least equally or even better tolerable than conventional interferon alfa[7,8,15-18]. Recent studies confirm this superiority of the pegylated drug over unmodified interferon alfa at least concerning quality of life[17,19].

However, improved tolerability of peginterferon has not yet been shown in studies focusing specifically on frequency and extent of neuropsychiatric symptoms as depression or hostility. On the other hand, previous studies have demonstrated that exactly these variables are relevant for potential cases of premature termination of antiviral therapy[11,20].

Therefore, we systematically investigated psychiatric symptoms in HCV-infected patients before, during, and after therapy with pegylated interferon alfa or conventional interferon alfa.

The main focus of the present study was to assess - in a longitudinal design - incidence, spectrum, and extent of psychiatric symptoms associated with interferon alfa therapy in patient subgroups treated with conventional or pegylated interferon alfa.

The participants were 109 consecutive patients in whom chronic hepatitis C was diagnosed at our institution or who were referred for interferon alfa therapy of known chronic hepatitis C. Eleven patients could not be included in the final evaluation and statistical analysis (dropouts): 6 patients receiving conventional interferon alfa (withdrawal of consent to study participation 3, insufficient compliance due to subjective intolerability 3) and 5 dropouts in the peginterferon group (withdrawal of consent to study participation 2; insufficient compliance due to subjective intolerability 1, coronary heart disease 1, epileptic seizure 1). All these patients had either prohibited the use of their data by withdrawal of their participation, or had not reached t3 as the first important evaluation time point. So, 98 of 109 recruited patients could finally be evaluated.

At the Medizinische Poliklinik (Clinic for Internal Medicine, Outpatient Department) of Würzburg University, a multispecialty group of physicians (specialists of gastroenterology/hepatology and psychosomatic medicine) cares for patients from a wide geographic radius on an outpatient and inpatient basis. The first set of patients were recruited in August 1998, and the latest data included in the present analysis were obtained in May 2003. Patients with documented antibody to HCV and serologic confirmation of active hepatitis C (HCV-RNA: sensitive assay based on reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction [Cobas-Amplicor HCV Monitor®; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland]) were included.

Patients were excluded from the study if they were aged under 18 years or over 65 or had co-infections such as with hepatitis B virus or human immunodeficiency virus, severe internal diseases (e.g., cancer, ischemic heart disease, autoimmune disease), major depressive disorder (according to DSM-IV criteria), psychosis, active intravenous drug use or alcohol abuse, obvious intellectual impairment, or insufficient knowledge of the German language. A history of a depressive episode in the past (at least 12 mo ago) was not an exclusion criterion.

This prospective, nonrandomized, and longitudinal study included 2 consecutive treatment groups (unmodified (n = 48) and pegylated (n = 50) interferon). Subjects eligible for the study were patients in whom therapy with interferon alfa was indicated and who gave written consent to receive this therapy and participate in the study before enrollment. The Ethics Committee for Medical Research of Würzburg University in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki approved the study.

According to the changing recommendations in Germany during the study period, patients were treated with interferon alfa-2b (5 MIU thics weekly) and ribavirin (recruitment between August 1998 and August 2000; 48/98; 45.7%), or with peginterferon alfa-2b (80-150 μg weekly; approximately 1.5 μg/kg) and ribavirin (recruitment between September 2000 and November 2002; 50/98 patients; 54.3 %). In the case of virological response, the respective therapy was given for a total of 12 mo (genotypes 1, 4) or 6 mo (genotypes 2, 3). All patients received oral ribavirin in a dose according to their body weight (daily dose: 800 mg for <65 kg; 1000 mg for 65-85 kg; 1200 mg for >85 kg). If the blood hemoglobin concentration fell below 10 g%, the daily ribavirin dose was reduced by 200-400 mg.

Before study entry, all eligible patients participated in a manualized structured interview (German version of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Revised[21]) conducted face-to-face by a psychologist to exclude severe psychiatric illness according to DSM-IV[22] classification (psychotic disorders, major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders) and to explain the nature and aim of the study. Sociodemographic factors recorded included gender and age. Data on the course of the disease and mode of infection were obtained as well.

In all patients, psychometric scores were obtained before therapy (t1) and after 4 wk (t2), 3 to 4 mo (t3), and 6 to 8 mo of interferon alfa medication (t4), as well as 4 wk (t5) after termination of therapy.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale Depression was assessed with the well-validated Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS, German version, as published by Herrmann[23]). HADS is a 14-item questionnaire with the dimensions anxiety and depression. All items exclusively refer to the emotional state and do not reflect somatic symptoms. The cut-off value for clinically relevant depressive symptoms was set to ≥9[23].

Symptom checklist-90 revised Anger/hostility was assessed by the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90-R, German version, as published by Franke[24]). The SCL-90-R is a brief, multidimensional self-report inventory designed to screen for a broad range of psychological problems and symptoms of psychopathology. We focused exclusively on the evaluation of one questionnaire subscale (subscale 6, “anger/hostility”). In accordance with the manual, the cut-off value for highly affected patients was set to ≥8[24].

Blood samples were obtained during the patients’ medical visits at time points t1-t5 to evaluate the following parameters: blood count, transaminases and HCV-RNA. Genotype identification, anti-HCV antibodies testing and liver biopsy (staging and grading: inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis) were performed once before interferon alfa therapy. However, a liver biopsy conducted immediately before study entry was not a mandatory inclusion criterion. The mode of infection was documented.

Data were registered and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows, German version 10.0.7)[25]. All tests of significance were 2-tailed. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Because of the explorative character of the study, we did not consider alpha adjustment in multiple comparisons.

Data describing quantitative measures are expressed as median or mean±SD or SE of the mean. Qualitative variables are presented as counts and percentages.

Tests of significance: Comparison of variables representing categorical data was performed using the χ2 statistic. Mean differences of continuous variables between patients subgroups were examined either by t tests for independent samples (comparison of 2 subgroups, e.g., unmodified interferon vs peginterferon group) or analysis of variance (ANOVA) if more than 2 subgroups (factor categories) were included. Group means of dependent samples (e.g., time course of continuous variables before, during and after interferon alfa therapy within the study sample) were compared by means of ANOVA (repeated-measures design, GLM procedure[25]). Corresponding contrasts (e.g., t1 vs t3) were tested using t-tests for dependent samples. Changes of counts or percentages over time were evaluated by Friedman’s (non-parametric) ANOVA.

Pearson’s correlation was used when appropriate (assessment of associations between quantitative variables).

The sociodemographic and biomedical characteristics of the 98 patients receiving therapy with either conventional or pegylated interferon alfa therapy are presented in Table 1. The distributions of the variables age, gender, virus genotype and grade of liver damage are comparable to those observed in other hepatitis C therapy studies.

| Characteristic | Total sample n = 98 | Peginterferon + ribavirin n = 50 | Interferon alfa-2b + ribavirin n = 48 | P |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 40.3±10.0 | 43.2±7.8 | 41.8±9.1 | 0.112 |

| Range | (18-65) | (23-63) | (18-65) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Women | 46 (46.9) | 26 (52.0) | 20 (41.7) | 0.306 |

| Men | 52 (53.1) | 24 (48.0) | 28 (58.3) | |

| Body Weight (kg) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 74.6±16.3 | 73.4±16.4 | 75.9±16.2 | 0.439 |

| Range | (47-132) | (48-115) | (47-132) | |

| Acquisition Mode, n (%) | ||||

| Unknown | 29 (29.6) | 18 (36.0) | 11 (22.9) | 0.263 |

| IVDU | 53 (54.1) | 26 (52.0) | 27 (56.3) | |

| Post Transfusion | 16 (16.3) | 6 (12.0) | 10 (20.8) | |

| Virus Genotype, n (%) | ||||

| Genotype 1 | 51 (52.0) | 26 (52.0) | 25 (52.1) | 0.46 |

| Genotype 2 | 12 (12.3) | 7 (14.0) | 5 (10.4) | |

| Genotype 3 | 33 (33.7) | 15 (30.0) | 18 (37.5) | |

| Genotype 4 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Liver Damage, 1n (%) | ||||

| Hepatitis only | 47 (50.0) | 18 (38.3) | 29 (61.8) | 0.065 |

| Fibrosis | 26 (27.7) | 17 (36.2) | 9 (19.1) | |

| Cirrhosis | 21 (22.3) | 12 (25.5) | 9 (19.1) | |

| Sustained Virological Response, n (%) | ||||

| Responder | 52 (53.1) | 28 (56.0) | 24 (50.0) | |

| Nonresponder | 46 (46.9) | 22 (44.0) | 24 (50.0) | 0.552 |

Patients’ characteristics were similar in both therapy subgroups with only one exception:

Patients receiving conventional interferon alfa showed according to the liver biopsy results a higher rate of “hepatitis only” diagnoses (61.8% vs 38.3%). However, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.065).

Interferon dose reduction (due to weight loss or intolerability) had to be performed in 7 cases (14.6%) in the standard interferon group and also in 7 patients (14%) receiving pegylated interferon alfa-2b.

Ribavirin dose reductions were performed in the case of hemolysis with blood hemoglobin decline. This was necessary in 10 patients (20.8%) in the standard interferon subgroup and in 9 patients in the peginterferon subgroup (18%).

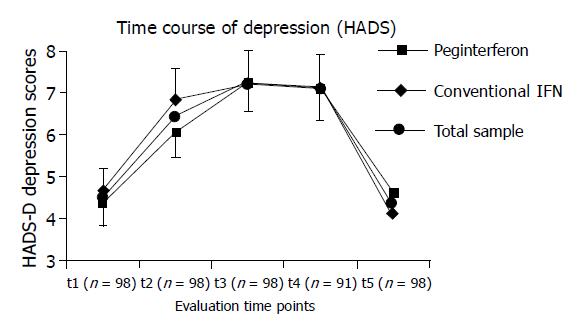

As expected and shown in Figure 1, HADS depression scores increased significantly in the total sample and returned to baseline level after termination of antiviral therapy (ANOVA main effect time: P<0.001).

The reduced sample size (Figure 1) during antiviral therapy can be explained as follows: T4 evaluation was not possible in 7 patients due to virological nonresponse (n = 2), major depressive episodes (n = 3), or nonpsychiatric intolerability (n = 2).

When comparing patient subgroups according to the respective therapy modes (pegylated vs conventional interferon), neither main effect medication (P = 0.875) nor interaction effect (time×medication; P = 0.494) turned out to be statistically significant for HADS depression scores. Figure 1 shows that in our study, patients receiving pegylated interferon alfa showed more slowly increasing HADS depression scores with a maximum at t3 and slightly exceeding the mean scores of the remainder subgroup after t2. However, this observation was not statistically significant. Therefore, in our study, time courses of depressive symptoms according to HADS scores were not significantly altered by the respective therapy mode.

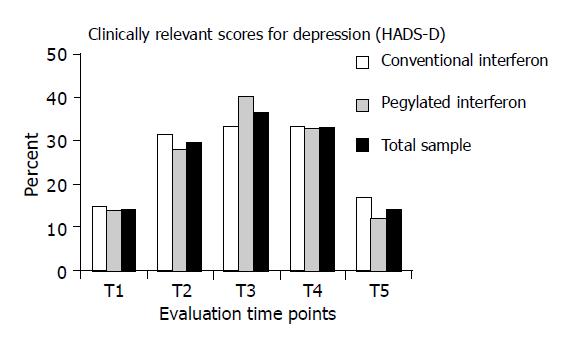

Percentages of study patients with (HADS) depression scores above the cut-off value (≥9) are displayed in Figure 2. As expected, there was a considerable increase of cases of relevant depression during antiviral therapy in the total sample.

In addition, the stratified presentation of the results for both therapy subgroups reveals that in patients receiving peginterferon alfa, there were slightly more cases of clinically relevant depression during therapy at time point t3 (40% vs 33.3%). However, the observed between-groups difference was not statistically significant (t3: P = 0.494).

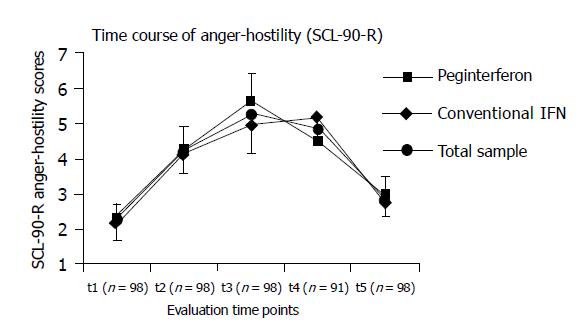

Evaluation of another potential interferon-induced adverse event hostility is displayed in Figure 3. The respective SCL-90-R subscale significantly increased during cytokine therapy within the total study population (P<0.001). Stratification for therapy subgroups did not reveal any marked differences with respect to the extent or qualitative time course of anger/hostility scores.

Rates of clinically relevant anger/hostility scores were not significantly different when comparing subgroups according to the respective therapy mode (data not shown).

Data from previously published studies suggest that - besides a significantly improved sustained virological response[7,8] - tolerability of therapy with pegylated interferon alfa may be improved as compared to medication with unmodified interferon alfa, regarding measures of health related quality of life. In a controlled study[19] comparing peginterferon alfa-2a with conventional interferon alfa-2a, the authors found less fatigue during treatment with pegylated interferon. Only during the initial phase of the study (2 and 12 wk), patients on pegylated interferon showed better scores in seven of the eight domains and both summary scores of the SF-36 quality of life questionnaire.

In another study in a sub-sample of 348 patients, Siebert et al[17] compared the cost-effectiveness of peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin and interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for the initial treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C. While their main focus was not on health-related quality of life, the authors conclude that according to their findings, the combination of peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin would improve the quality of life, and be cost-effective for the initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C.

However, systematic and prospective data with the main focus on quality and extent of neuropsychiatric symptoms (depression, anger/hostility) comparing unmodified and pegylated interferon alfa have not been published so far. There have been only a few studies on (neuro-) psychiatric side effects in either conventional or pegylated interferon alfa[12-14,16,26-29].

Therefore, we performed the present study in a longitudinal design, focusing on the most relevant psychiatric side effects, including the two consecutive patient subgroups receiving unmodified and pegylated interferon alfa respectively. We followed a study design fulfilling the following criteria: evaluation and comparison of psychiatric symptoms as the main focus, sufficient sample size, and use of well-validated and applicable psychometric instruments. To ensure homogeneity concerning data acquisition and patient care, the study was performed in a single center. Since at the time when patient recruitment started, only conventional interferon was available, the study was performed in a nonrandomized design with sequential inclusion of the 2 treatment groups. Patient care was comparable for both groups, and was provided by the same staff over the whole study period. Therefore, an influence of factors other than the different therapies on the patients’ mental state is unlikely.

An additional control group was not considered necessary: Firstly, it would not have been possible for ethical reasons to include a group of untreated hepatitis C patients in whom interferon therapy is clearly indicated. Moreover, although the presence of hepatitis C infection itself might account to some extent for the depression scores observed, this would not affect the message of our study, since we did not focus on absolute values.

Finally, in a previous study[12] we included a “reference group” (untreated hepatitis C patients in whom antiviral therapy was not indicated). It was shown that the values for the psychometric variables remained stable over time in these patients.

Although an improved quality of life[17,19] during peginterferon treatment certainly represents a major advantage over former therapy modes, the present study has become necessary because incidence and severity of interferon-induced psychiatric symptoms are significantly associated with premature discontinuation of antiviral therapy and cannot be easily derived from measures of quality of life[13,14,30].

According to our data, frequency and extent of interferon-induced neuropsychiatric adverse events are not significantly reduced when applying the pegylated form of the drug. In contrast to measures of health-related quality of life in other works[17,19], mainly depression and anger/hostility are similar in the subgroups with conventional or pegylated interferon alfa. This is in concordance with findings in studies with efficacy (sustained virological response) as main issue[8,15].

As interferon-associated side effects are dose-dependent, the higher dose applied in our study (5 MIU thrice weekly) may have influenced the results. It cannot be excluded that patients receiving standard interferon alfa-2b at the dose used in most licensing studies (3×3 MIU weekly) would show even lower scores of depression or anger/hostility as compared to patients receiving pegylated interferon alfa. However, a more favorable outcome with the lower interferon dose would not affect our main issue that the spectrum of psychiatric side effects caused by peginterferon is not superior to the one caused by conventional interferon.

However, in our study sample, depression scores increased more slowly and reached a higher maximum in patients receiving peginterferon as compared to the subgroup with conventional interferon alfa, but this difference was not statistically significant.

We are aware of the fact that these results cannot prove that depressive symptoms are identical for both therapy modes. Nevertheless, our sample size (n = 98) was large enough to detect clinically relevant effect sizes regarding between-group differences of depression scores. A clinically relevant difference of at least 2 points on HADS depression scale (effect size of 0.5) would have been detected with statistical significance within our study design and sample size.

(Largest between-group difference in depression scores: 0.75 at t2, representing a very small effect size (about 0.17). This difference is clinically insignificant in order to detect such small between-group differences, the total sample size would have to exceed 850 patients).

As a consequence, application only once weekly and more constant interferon alfa serum levels (as a result of pegylation of interferon alfa) do not automatically lead to a marked improvement of drug tolerability especially in the field of neuropsychiatric toxicity.

This partly contradicts the results of Rasenack et al[19] and several other studies, claiming a tolerability of peginterferon medication, which is at least as good as or even better than the conventional interferon alfa. However, it has to be added that the higher (cumulative) weekly dose of pegylated interferon (80 mg once weekly vs 5 MIU tiw when standard interferon is used) does not lead to significantly impaired tolerability of the pegylated formulation either. (It cannot be excluded that when comparing equivalent weekly doses of both types of interferon, the tolerability might be improved in/favorable for peginterferon).

To summarize, according to our results, psychiatric symptoms are still very common during current antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Tolerability is not significantly changed when using pegylated instead of unmodified interferon alfa when regarding specific psychiatric symptoms such as depression and anger/hostility. Time courses of scores for depression and anger/hostility as well as rates of clinical relevant scores were in a similar range when both therapy subgroups were analyzed and compared.

Regarding the high extent and frequency of e.g., depressive symptoms, we suggest that the consideration, monitoring, and management of neuropsychiatric side effects continue to merit the same attention and care in patients receiving peginterferon as already pointed out[12,13] for former interferon-based therapy modes.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Davis GL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C. BMJ. 2001;323:1141-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C in the West. Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15:5-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1997;26:62S-65S. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2042] [Cited by in RCA: 2025] [Article Influence: 84.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Luxon BA, Grace M, Brassard D, Bordens R. Pegylated interferons for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1363-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hoofnagle JH. Chronic viral hepatitis C - clinical. Postgraduate Course, Chicago, 1998. Association for the study of liver diseases. . |

| 7. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4736] [Cited by in RCA: 4558] [Article Influence: 189.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4847] [Cited by in RCA: 4748] [Article Influence: 206.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kraus MR, Schäfer A, Csef H, Scheurlen M, Faller H. Emotional state, coping styles, and somatic variables in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:377-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kraus MR, Schäfer A, Scheurlen M. Paroxetine for the prevention of depression induced by interferon alfa. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:375-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kraus MR, Schäfer A, Faller H, Csef H, Scheurlen M. Paroxetine for the treatment of interferon-alpha-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1091-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kraus MR, Schäfer A, Faller H, Csef H, Scheurlen M. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with chronic hepatitis C receiving interferon alfa-2b therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:708-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Russo MW, Fried MW. Side effects of therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1711-1719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dieperink E, Ho SB, Thuras P, Willenbring ML. A prospective study of neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with interferon-alpha-2b and ribavirin therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis C. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:104-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Rasenack J, Heathcote EJ, Lai MY, Gane E, O'Grady J, Reichen J, Diago M, Lin A. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1666-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 883] [Cited by in RCA: 851] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fried MW. Side effects of therapy of hepatitis C and their management. Hepatology. 2002;36:S237-S244. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Siebert U, Sroczynski G, Rossol S, Wasem J, Ravens-Sieberer U, Kurth BM, Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Wong JB. Cost effectiveness of peginterferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin versus interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2003;52:425-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Perry CM, Jarvis B. Peginterferon-alpha-2a (40 kD): a review of its use in the management of chronic hepatitis C. Drugs. 2001;61:2263-2288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rasenack J, Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Heathcote EJ, Manns M, Yoshida EM, Swain MG, Gane E, Diago M, Revicki DA. Peginterferon alpha-2a (40kD) [Pegasys] improves HR-QOL outcomes compared with unmodified interferon alpha-2a [Roferon-A]: in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21:341-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, Goodman ZD, Ling MH, Cort S, Albrecht JK. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2509] [Cited by in RCA: 2434] [Article Influence: 90.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Margraf J, Schneider S, Ehlers A. Diagnostisches interview bei psychischen störungen (german modified version of ADIS-R anxiety disorders interview schedule-revised; DiNardo PA, Barlow DH, 1988). Berlin: Springer 1994; . |

| 22. | Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition: DSM-IV. In: Association AP, ed. Washington D.C. : American Psychiatric Association 1994; . |

| 23. | Herrmann C, Buss U, Snaith RP. HADS-D. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - Deutsche Version. Ein fragebogen zur erfassung von angst und depressivität in der somatischen medizin. Bern: Huber 1995; . |

| 25. | Franke GH; SPSS. SPSS für Windows 10.0.7. Chicago: SPSS Inc 2000; . |

| 26. | Valentine AD, Meyers CA, Kling MA, Richelson E, Hauser P. Mood and cognitive side effects of interferon-alpha therapy. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:39-47. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Fontana RJ. Neuropsychiatric toxicity of antiviral treatment in chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis. 2000;18:107-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bonaccorso S, Marino V, Biondi M, Grimaldi F, Ippoliti F, Maes M. Depression induced by treatment with interferon-alpha in patients affected by hepatitis C virus. J Affect Disord. 2002;72:237-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bonaccorso S, Marino V, Puzella A, Pasquini M, Biondi M, Artini M, Almerighi C, Verkerk R, Meltzer H, Maes M. Increased depressive ratings in patients with hepatitis C receiving interferon-alpha-based immunotherapy are related to interferon-alpha-induced changes in the serotonergic system. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22:86-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kraus MR, Schäfer A, Csef H, Faller H, Mörk H, Scheurlen M. Compliance with therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: associations with psychiatric symptoms, interpersonal problems, and mode of acquisition. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2060-2065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |