INTRODUCTION

Actinomycosis is a rare, chronic, spreading, suppurative, granulomatous and fibrosing infection characterized by the formation of multiple abscess, draining sinuses and the release of characteristic “sulfur granules”[1]. This infection is normally caused by Actinomyces israelii, which are anaerobic gram-positive filamentous rods. These organisms are not regarded as virulent human pathogens and are best considered as opportunistic pathogens, as they are normally present in healthy individuals, especially in the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract[2,3]. This disease usually follows perforation of an abdominal viscus because of inflammatory or neoplastic disease, surgery, or trauma[4-7] and has also commonly associated with the long-term use of an intrauterine device[8-10]. Herein, we reported a patient who had undergone Whipple’s operation due to ampulla Vater carcinoma, and succumbed to actinomycosis at the pancreaticojejunostomy, which mimicked local recurrence of cancer. He was treated with radical resection of the mass and had an uneventful postoperative course. He regained body weight steadily and had no recurrence of actinomycosis at the postoperative 6 mo follow-up.

CASE REPORT

A 69-year old male patient was referred to our hospital because of common bile duct (CBD) stone with biliary tract infection with an initial presentation of abdominal fullness, general malaise, nausea, vomiting, poor appetite and body weight loss for 2 wk. A panendoscopy revealed an enlarged, easy touch-bleeding papilla with an infiltrating mass. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed a dilated biliary tree and pancreatic duct with stricture of the distal CBD and pancreatic duct (double duct sign). The serum level of the carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) was 126.26 u/mL. Biopsy of the ampulla Vater demonstrated moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. He then received a radical pancreaticoduodenectomy with Child’s reconstruction. A right subhepatic abscess was noted 10 d after the operation and was managed by computed tomography (CT) guidance percutaneous drainage. The patient was discharged 3 wk after surgery and received regular follow-ups at our outpatient department.

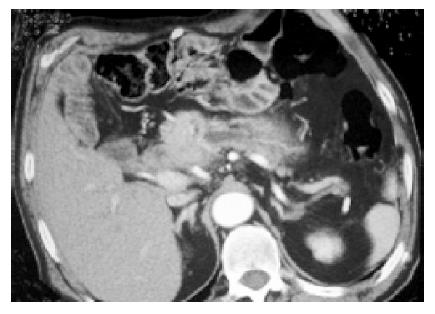

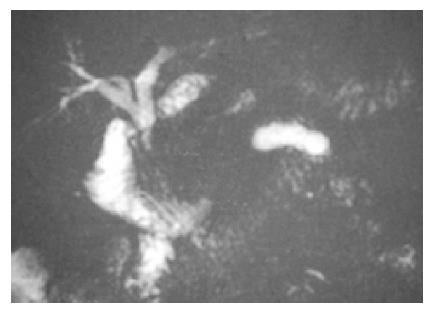

Unfortunately, an abdominal CT scan showed abnormal soft tissue enlargement at the pancreaticojejunostomy (Figure 1) 2 years after surgery. Meanwhile, the CA19-9 level had also elevated comparing to the immediate postoperative value (from 4.43 to 50.63 u/mL). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed tapering of distal bile duct with upstream dilation and a dilated pancreatic duct with sudden obliteration at the pancreaticojejunostomy (Figure 2). The patient had no fever, leukocytosis or jaundice (white blood cells, 5900/mm3; total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL). Only body weight loss of about 10 kg and fatigue had been noted over the last 2 mo. Therefore, he received surgery again under the strong impression of a suspected local recurrence of ampulla Vater carcinoma.

Figure 1 Abdominal CT scan reveals abnormal soft tissue enlargement at the pancreaticojejunostomy.

Figure 2 MRCP depicts tapering of the distal bile duct with upstream dilatation and a dilated pancreatic duct with sudden obliteration at the pancreaticojejunostomy.

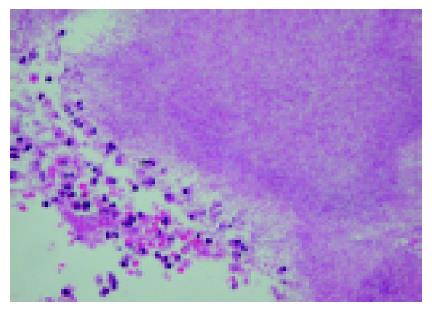

During the operation, a hard mass at the pancreati-cojejunostomy with extension to para-aortic area and stenosis of previous pancreaticojejunostomy was identified. A frozen section revealed no evidence of malignancy. Nevertheless, the mass was resected and the pancreaticojejunostomy was re-constructed. The final pathology showed transmural inflammation of the segment of resected jejunum. There were many sulfur granules, which were positive for Periodic acid and Giemsa stains (Figure 3), consistent with actinomycosis. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course without administration of penicillin and was discharged home 2 wk after operation with steady regaining of body weight.

Figure 3 Histopathological examination demonstrates many sulfur granules, which are positive for Periodic acid and Giemsa stains, which is consistent with actinomycosis.

DISCUSSION

Actinomycosis, which was first described by Israel in 1878[11], is a rare, chronic, spreading, suppurative, granulomatous and fibrosing infection characterized by the formation of multiple abscesses, draining sinuses and the release of characteristic “sulfur granules”[1]. It is found worldwide and occurs at any age, but is rare at ages younger than ten. The peak incidence is between 15 and 30 years, and males are more frequently infected than females[2].

Actinomyces are anaerobic, gram-positive bacteria that form filaments[12]. They are normally present in healthy individuals, especially in the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract[2,3]. All tissues and organs can be infected[3] when the mucosal barrier is broken, leading to multiple abscess formation, fistula, or a mass lesion[2,4]. Actinomycosis commonly occurs in three distinct forms. The majority of examples of the clinical disease are cervicofacial (55%), with only 20% occurring in an abdominopelvic form and 15% as a thoracopulmonic form[7,13]. Abdominopelvic actinomycosis has been associated with abdominal surgery, such as appendectomy, or bowel perforation, diverticulitis, trauma, foreign bodies and neoplasia[5-7,14-16]. Establishment of human infection may also require the presence of companion co-infection bacteria, which releases a toxin or enzyme inhibiting the host defenses. This enhances the relatively low invasive power of actinomycetes. Immune suppression and (surgical) trauma may also play an important role. Various abdominal organs may be involved in abdominopelvic actinomycosis including the gastrointestinal tract, ovaries, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas[2,17]. To the best of our knowledge, actinomycosis at a pancreaticojejunostomy has not been reported in the literature. In our case, the immune suppression due to ampulla Vater carcinoma along with the surgery and postoperative subhepatic abscess formation might have contributed to the development of the actinomyces infection.

In most cases, patients present with an abdominal mass were frequently mistaken for a neoplasm, as was the case here. At a more advanced stage, the abdominal mass is accompanied with extensive sinus, fistula, and abscess formation, usually draining to the skin. Although the clinical features depend on which organs are involved, common symptoms and signs include fever and leukocytosis, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and night sweats[2,14,15,18]. Our case presented with only body weight loss and fatigue without fever or leukocytosis, which led to the reasonable preoperative diagnosis of a cancerous recurrence rather than actinomycosis. Most adjunctive diagnostics are very not very specific. In only 10% of the cases is the diagnosis made preoperatively[19] and differentiation from a malignancy is very difficult[14,20]. A CT scan can be helpful in locating and determining the extent of the lesion. Additionally, CT-guided fine needle aspiration of the mass may help diagnosis by cytological examination[15].

High-dose intravenous penicillin injection is the treatment of choice[7,21] and the response is usually favorable[13,22,23]. Therefore, early diagnosis is important to minimize morbidity due to this disease and avoid unnecessary surgery. However, the diagnosis is often obtained postoperatively from a pathology report. Surgery is reasonable and usually necessary because of the difficulty of diagnosis. Debridement of necrosis and relieving the related symptoms such as obstruction and cramping pain can be quickly achieved by surgery. In our case, an intra-operative frozen section of the mass at pancreatojejunostomy revealed only chronic inflammation without any evidence of malignancy. Resection of the mass was justified to rule out the recurrence of ampulla Vater carcinoma and to relieve the pancreatic duct obstruction. Postoperative penicillin was not administered to this patient because a radical resection of the actinomycosis was carried out and no sign of clinical infection was found.

Because of its rarity, intramural actinomycosis is an entity that is often overlooked by most surgeons. A high index of suspicion may help increase awareness of this important and curable disease. Actinomycosis should be taken into account as a differential diagnosis in patients having an intra-abdominal mass with unusual fever or leukocytosis after gastrointestinal surgery.

In summary, actinomyces rarely cause disease and are seldom reported as human pathogens. The symptoms of actinomycosis are non-specific, which leads to great diagnostic difficulty. Actinomycosis should be considered when a cancerous patient, after gastrointestinal surgery, experiences an intra-abdominal mass along with unexplained fever or leukocytosis. Penicillin G is still the medical treatment of choice. However, surgical intervention can still play a role in facilitating the recovery in selected patients and is useful to rule out malignancy in some instances. For this particular patient, re-operation was justified to rule out the recurrence of ampulla Vater carcinoma and to relieve the pancreatic duct obstruction.