Published online Apr 15, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i8.1103

Revised: November 3, 2003

Accepted: December 30, 2003

Published online: April 15, 2004

AIM: To analyze the clinicopathologic characteristics of surgically resected gastric lymphoma patients.

METHODS: We retrospectively analyzed 57 surgically resected gastric lymphoma patients, dividing them into 2 subgroups: Low grade MALToma (the LG group), High grade MALToma and Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (the HG group).

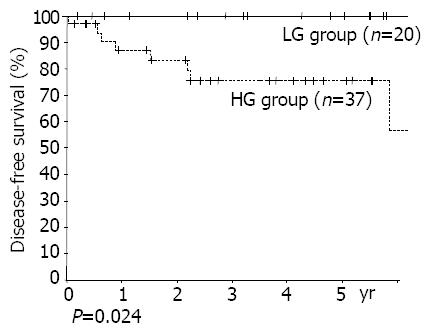

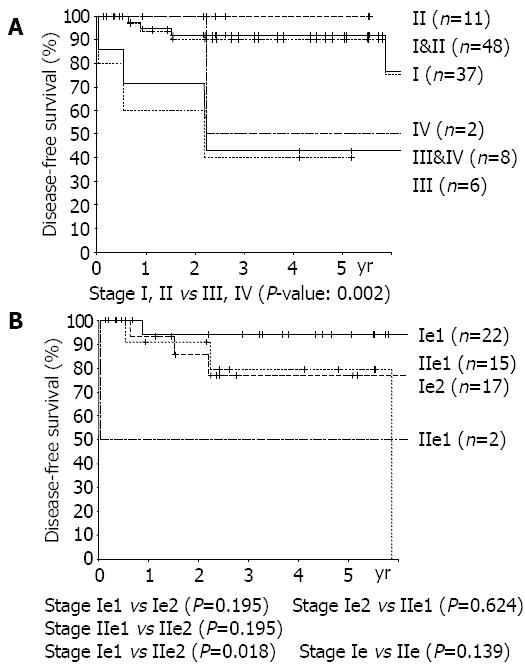

RESULTS: The numbers of patients were: 20 in the LG group, 37 in the HG group. The diagnostic rate of gastroscopy was 34.8% at primary diagnosis and 50% including differential diagnoses. The positive rates of H pylori were similar between the 2 groups (68% vs 77%). Multiple lesions were found in 19.3%. The proportion of mucosal and submucosal lesions was 80.0%(16/20) in the LG group, and 24.3%(9/37) in the HG group (P<0.001). Lymph node invasion rates were 10.5%(2/19) in the LG group and 44.1%(15/34) in the HG group (P = 0.031). The numbers of recurred patients were none in the LG group, and 8 in the HG group. By univariant analysis, group (P = 0.024) and TNM stage (stage I, II vs stages III, IV, P = 0.002) were found to be the significant risk factors. There was a tendency of higher recurrence rate in the subtotal gastrectomy group than in the total gastrectomy group (P = 0.50).

CONCLUSION: The HG groups had a more advanced stage and a higher recurrence rate than the LG group. Although there was no difference between subtotal and total gastrectomies, more careful assessments of multiplicities and radical resections with lymph node dissections seem to be needed because of multiplicity and LN invasion even in LG group.

- Citation: Kong SH, Kim MA, Park DJ, Lee HJ, Lee HS, Kim CW, Yang HK, Heo DS, Lee KU, Choe KJ. Clinicopathologic features of surgically resected primary gastric lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(8): 1103-1109

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i8/1103.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i8.1103

Because primary gastric lymphoma has a tendency to be localized in the stomach for a long time, surgical resection remains an important treatment modality[1-3]. Helicobacter pylori has been proposed to be an important cause of the formation of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) and the development of subsequent lymphoma. About 80% of low grade MALT lymphomas were found to be cured by H pylori eradication alone, and there are some reports in which high grade MALT lymphoma was also cured in this manner[4]. Recently, lymphoma related with MALT was classified as ‘extra nodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma)’ by WHO[5]. According to the report of Isaacson et al.[6] in 1983, gastric lymphoma may be divided into low grade MALT lymphoma, high grade MALT lymphoma, and diffuse large B cell lymphoma. The aim of this study was to analyze the clinicopathologic characteristics of surgically resected gastric lymphoma patients according to the postoperative histopatholgic grades.

We enrolled 57 gastric lymphoma patients who had undergone operations at Seoul National University Hospital from January 1995 to July 2002.

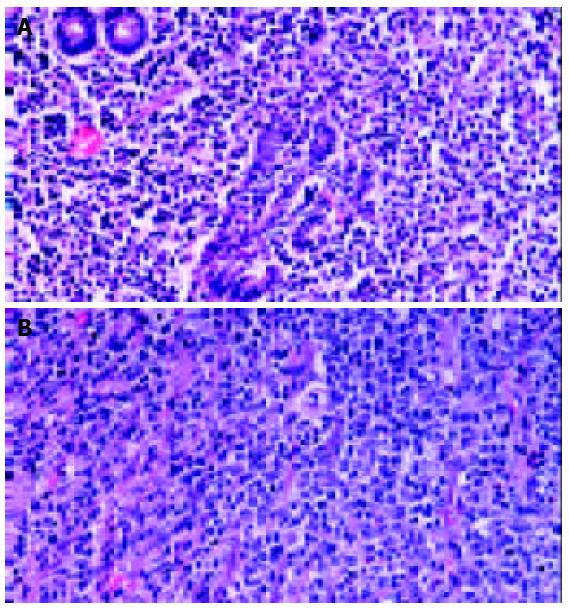

Primary gastric lymphoma was often divided into 3 categories: low grade MALT lymphoma, high grade MALT lymphoma, and diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Low grade MALT lymphoma was diagnosed when the classic features of MALT lymphoma were evident. The classic features were lymphoid atypical cells and destruction of mucosal walls (lymphoepithelial lesion), and the presence of centrocyte-like cells, lymphoid follicles, monocyte-like B-cells, lympho-plasma cell, centroblast-like cells, and Dutcher bodies[7,8]. When these cells became larger and crowded, and the features of low grade MALT lymphoma were seen partly, such cases were classified as high grade MALT lymphoma. When portions of low grade MALT lymphoma were absent, they were classified as diffuse large B cell lymphoma. (Figure 1) But, it was often difficult to differentiate diffuse large B cell lymphoma from high grade MALT lymphoma because the histopathologic sections from postoperative specimens sometimes did not include the portions of the classic features of low grade MALT lymphoma which were present partly.

We divided the patients into 2 groups according to the post-operative pathologic reports, namely the LG group (low grade MALT lymphoma) and the HG group (high grade MALT lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma).

Sex, age, operative method, postoperative stage, number of lesions, and recurrence were reviewed retrospectively using medical records and phone-call surveillance. For postoperative staging, both the TNM staging system for gastric adenocarcinoma and the Musshoff staging system (modified Ann-Arbor stages) were used (Table 1).

| Stage | Definition |

| Ie | Involvement of a single extralymphatic organ or site1 |

| Ie1 | Involvement of mucosa or submucosa |

| Ie2 | Involvement of more than submucosa |

| IIe | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm |

| with localized involvement of an extralymphatic organ and site1,2 | |

| IIe1 | Involvement of regional lymph nodes |

| IIe2 | Involvement of other lymph nodes beyond regional area |

| IIIe | Localized involvement of a single extralymphatic organ or site with involvement of lymph node regions on |

| both sides of the diaphragm (IIIe) or involvement of the spleen (IIIs) or both (IIIe+s)1,2 | |

| IVe | Involvement of extranodal site(s) beyond that designated as “e” more than one extranodal |

| deposit at any location, any involvement of liver or bone marrow1,2 | |

| E | localized, solitary involvement of extralymphatic tissue, excluding liver and bone marrow |

| 1 | Direct spread of a lymphoma into adjacent tissues or organs does not influence stage. Multifocal involvement of a single extralymphatic organ is classified as stage IE and not stage IV. Involvement of two or more segments of the gastrointestinal tract, isolated and not in continuity, is classified as stage IV (disseminated involvement of one or more extralymphatic organs). |

| 2 | The definitions of regional lymph nodes for individual sites of extranodal lymphomas are identical to the definitions of regional lymph nodes for individual sites of gastrointestinal carcinomas. For example, the regional lymph nodes for a primary gastric lymphoma are the perigastric nodes along the lesser and greater curvatures and the nodes located along the left gastric, common hepatic, splenic, and celiac arteries. |

Clinicopathologic data were compared using the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. Survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and analyzed using the log-rank test. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The numbers of patients of the LG group and the HG group were 20(35.1%) and 37(64.9%), respectively. One patient had a synchronous gastric adenocarcinoma and low grade MALT lymphoma.

The male to female ratio was 1.11:1 (30:27) without any significant difference between the groups.

The mean age of the patients in the LG group was 52.6 years, and was 57.7 years in the HG group. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups. (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Epigastric pain and discomfort were the most common symptoms. The duration of the symptoms of the LG group had a tendency to be longer than that of the HG group, but it was not statistically significant. Among B symptoms specific in lymphoma, only weight loss was found in 9 patients (15.8%), but fever and night sweats were not found. Moreover, the reason of weight loss was obscure, i.e., as to whether it was a part of the B symptoms or a result of the gastrointestinal symptoms (Table 3).

| Symptom | n (%) |

| Epigastric pain, discomfort | 39 (68.4) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 9 (15.8) |

| Weight loss | 9 (15.8) |

| Indigestion | 7 (12.3) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 4 (7.0) |

| Anorexia | 4 (7.0) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (3.5) |

| Others | 3 (5.3) |

| No Symptom | 6 (10.5) |

| Histopathology | Duration of symptom |

| LG group | 11.9 ± 24.9 |

| HG group | 5.2 ± 9.0 |

| Total | 7.6 ± 16.7 mo |

| P = n.s. |

Forty-six patients were enrolled whose records of preoperative gastroscopic findings were available. The accuracy of the primary diagnosis of lymphoma by preoperative gastroscopy was 34.8%(16/46), and the overall diagnosis rate including differential diagnosis was 50%(23/46) (Table 4).

| LG group (%) | HG group (%) | Total (%) | |

| Lymphoma | 6 (37.5) | 10 (33.3) | 16 (34.8) |

| AGC | 4 (25.0) | 17 (56.7) | 21 (45.7) |

| EGC | 5 (31.3) | 2 (6.7) | 7 (15.2) |

| Benign ulcer | 1 (6.3) | 1 (3.3) | 2 (4.3) |

| Total | 16 (100) | 30 (100) | 46 (100) |

| Dx. Rate | Lymphoma/total (%) | ||

| Primary Dx | 6/16 (37.5) | 10/30 (33.3) | 16/46 (34.8) |

| D/Dx | 8/16 (50.0) | 15/30 (50.0) | 23/46 (50.0) |

There were 2 cases of adenocarcinoma in the preoperative pathologic reports. One was misdiagnosed as a adenocarcinoma and later diagnosed as a diffuse large B cell lymphoma postoperatively, and the other was a case of synchronous adenocarcinoma and lymphoma. The accuracy of histological grading of lymphoma with preoperative biopsy was 87.0%(40/46) as compared with the postoperative pathologic reports (Table 5).

| Postop. | LG group (%) | HG group (%) | Total (%) |

| Preop. | |||

| LG group | 15 (78.9) | 4 (21.1) | 19 (100.0) |

| HG group | 2 (7.4) | 25 (92.6) | 8 (100.0) |

| Total | 17 | 29 | 46 |

To identify relationships with H pylori, a pathologic examination with or without a CLO test was used in 38 cases, the serology test (H pylori IgG) in 1 case, and both methods in 3 cases.

In our series, 73.8%(31/42) were related with H pylori. According to the groups, the positive rate of H pylori was 68.8%(11/16) in the LG group and 76.9%(20/26) in the HG group. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups.

Of the patients diagnosed as low grade MALT lymphoma, 5 patients took the regimen for H pylori eradication. Four patients had surgical resection later because of remnant lymphoma at follow-up gastroscopy, and 1 patient underwent the operation because of transformation to a higher grade.

Subtotal gastrectomy was performed in 35 patients (61.4%), and total gastrectomy in 22 patients (39.6%), with no significant difference among the groups. Of these 22 patients, 7 also underwent splenectomy (Table 6).

| LG group (%) | HG group (%) | Total (%) | |

| Subtotal gastrectomy | 10 (50.0) | 21 (56.8) | 30 (52.6) |

| Other partial gastrectomy | 2 (10.0) | 3 (8.1) | 5 (8.8) |

| Total gastrectomy | 8 (40.0) | 14 (37.8) | 22 (38.6) |

| TG | 7 (35.0) | 8 (21.6) | 15 (26.3) |

| TG + splenectomy | 1 (5.0) | 6 (16.2) | 7 (12.3) |

| Total | 20 (100) | 37 (100) | 57 (100) |

In all groups, the lower third was the most common lymphoma location, which occurred in 45.6%(26/57). If the patients with additional lesions in the upper or middle third were included, totally 54.4% (31/57) of patients had lesions in the lower third of the stomach. There was no significant difference between the groups (Table 7).

| LG group (%) | HG group (%) | Total (%) | |

| Lower 1/3 | 7 (35.0) | 19 (51.4) | 26 (45.6) |

| Middle 1/3 | 8 (40.0) | 10 (27.0) | 18 (31.6) |

| Upper 1/3 | 3 (15.0) | 5 (13.5) | 8 (14.0) |

| Lower + middle | 2 (10.0) | 2 (5.4) | 4 (7.0) |

| Lower + upper | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (1.8) |

| Total | 20 (100) | 37 (100) | 57 (100) |

We used both staging systems, namely TNM stages and Musshoff stages (modified Ann-Arbor stages). Regardless of the staging system, patients in the LG group had more proportions of early lesions than those in HG group (Tables 8-9).

| Stage | LG group (%) | HG group (%) | Total (%) |

| Ia (+ no residual) | 15 (78.9) | 7 (18.9) | 22 (39.3) |

| Ib | 3 (15.8) | 12 (32.4) | 15 (26.8) |

| II | 0 (0.0) | 11 (29.7) | 11 (19.6) |

| IIIa | 0 (0.0) | 6 (16.2) | 6 (10.7) |

| IV | 1 (5.3) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (3.6) |

| Total | 191 (100) | 37 (100) | 56 (100) |

| Stage | LG group (%) | HG group (%) | Total (%) |

| Ie1 (+ no residual) | 15 (78.9) | 7 (18.9) | 22 (39.3) |

| Ie2 | 2 (10.5) | 15 (40.5) | 17 (30.4) |

| IIe1 | 1 (5.3) | 14 (37.8) | 15 (26.8) |

| IIe2 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (3.6) |

| Total | 191 (100) | 37 (100) | 56 (100) |

In the LG group, mucosal and submucosal lesions accounted for 80.0%(16/20), lesions invading into proper muscles accounted for 15.0%(3/20). In the HG group, the proportion of lesions within the submucosa was 24.3%(9/37), lesions in proper muscles and subserosal spaces were 62.2%(23/37), and lesions invading serosa were 8.1%(3/37).

In the HG group, one patient had the lesion invading the colon and pancreas, and one patient had a lymphoma directly invading the spleen and pancreas.

The LG group had a lower proportion of LN metastasis than the HG group. The number of patients who had regional LN invasion was 2 of 19 (10.5%, 1 submucosal lesion, 1 proper muscle lesion) in the LG group and 15 of 34(44.1%) in the HG group.

Multiple lesions were found in 11 patients (19.3%) according to the postoperative pathologic reports. In 2 cases, no lymphoma lesion was found in the postoperative specimens, one had a diffuse large B cell lymphoma which received preoperative chemotherapy (COPBLAM #6), and the other was diagnosed as low grade MALT lymphoma preoperatively who did not receive any special therapy before operation. There was no difference in the proportions of multiple lesions among the subgroups. In 11 patients with multiple lesions, 6 had subtotal gastrectomy, and the other 5 had total gastrectomy (Table 10).

| Number | LG group (%) | HG group (%) | Total (%) |

| None or single | 17 (85.0) | 29 (83.3) | 46 (80.7) |

| 0 | 1 (5.0) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (3.5) |

| 1 | 16 (80.0) | 28 (75.7) | 44 (77.2) |

| Multiple | 3 (15.0) | 8 (21.6) | 11 (19.3) |

| 2 | 1 (5.0) | 7 (18.9) | 8 (14.0) |

| 6 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (1.8) |

| Diffuse | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.5) |

| Total | 20 (100) | 37 (100) | 57 (100) |

Postoperative radiotherapy was indicated to those with remnant lesions in their resection margins. Two patients in the LG group and one in the HG group underwent radiotherapy, and remained alive at postoperative 13.5 mo, 66.3 mo, and 66.4 mo, respectively, without evidence of recurrence. Postoperative chemotherapy was applied to one patient with low grade MALT lymphoma invading the proper muscles and the regional LN. Twenty-four patients out of 32 patients (75.0%) in the HG group had postoperative chemotherapy. According to the Musshoff stage, only 1 patient of 19 stage Ie1 patients had postoperative chemotherapy. Ten of 15 stage Ie2 patients and 14 of 15 stage IIe patients received chemotherapy. In most cases, CHOP regimen (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) was used.

Patients were followed up for a mean 75.8 mo. Eight cases had recurrence, no patient in the LG group and 8 patients (21.6%) in the HG group (Table 11).

| Sex/age | Op. | Loc. | Size(cm) | N | T | LN | Musshoff stage | Site of recurrence | DFS (mo) | Survival | OS (mo) |

| F/80 | ST | LB | 6x3 | 1 | PM | 8/26 | IIe2 | abdominal LN | 0.4 | Dead1 | 10.1 |

| M/34 | T | MB | 8x2.5 | 1 | PM | 12/21 | IIe1 | abdominal LN, | 6.6 | Dead | 9.1 |

| bone marrow | |||||||||||

| M/34 | ST | MB | 2.2x3 | 1 | SS | 0/60 | Ie2 | remnant stomach | 7.6 | Alive | 57.2 |

| F/59 | ST | LB | 4x3.5 | 1 | SM | 0/19 | Ie1 | paraaortic LN | 10.4 | Alive | 13.4 |

| M/85 | ST | MB & LB | 4x3 | 2 | PM | 0/64 | Ie2 | chest | 18.2 | Dead2 | 42.0 |

| F/55 | T | HB | 13x10 | 1 | colon, | 0/11 | Ie2 | abdominal LN | 26.3 | Dead | 37.4 |

| pancreas | |||||||||||

| M/67 | ST | LB | 10x8 | 1 | SS | 16/53 | IIe1 | cervical LN | 26.8 | Dead3 | 31.6 |

| M/70 | ST | MB | 3x2 | 2 | SM | 5/19 | IIe1 | unknown3 | 70.4 | Dead | 70.6 |

| 1.5x0.8 | |||||||||||

The locations of the recurrence were the remnant stomach in 1 case, and the intraabdominal lymph nodes in 4 cases. In the other case, the location was presumed to be the intraabdominal area. One case had a recurred lesion in the thorax, and another case in the neck.

Six of 8 patients with recurred diseases died. One died of pneumonia during chemotherapy for a recurred lymphoma, and another died of brain infarct of unknown etiology. The other 4 patients died of recurred disease progression.

Grades (P = 0.024), TNM stages (stages I, II vs stages III, IV, P = 0.002) were found to be risk factors by univariate analysis. Otherwise, age, sex, size of lesion, depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, and the presence of multiple lesions, were all unrelated to recurrence (Figures 2, 3). Patients with Musshoff stage IIe lymphoma showed a tendency of lower 5 years disease-free survival rate than those with stage Ie lymphoma (87.1% vs 76.1%, P = 0.139), but it was not significant. None of stage Ie patients in LG group had recurrence, but 4 of stage Ie HG group patients had recurrence (5-year disease-free survival rate 100% vs 77.9%, P = 0.080).

The recurrence rate in the subtotal gastrectomy group (17.1%, 6/35) was slightly higher than that in the total gastrectomy group (9.1%, 2/22). In the HG group, the recurrence rate was 28. 6%(6/21) in those with subtotal gastrectomy and 15.4%(2/13) in those with total gastrectomy. But it was not significant (P = 0.50).

The stomach is the most common intraabdominal organ for extralymphatic lymphoma in the abdominal cavity, about 20% of extralymphatic lymphomas occur in the stomach. Normally, the stomach has no lymphatic tissue in the mucosa or submucosa. The formation of MALT has been known to be related with H pylori and some autoimmune diseases[9,10]. In our study, the proportion of patients with evidences of H pylori was 73.8% overall, and 68.8% in the low grade MALT lymphoma group. This result corresponded with the results of Paik et al.[11] in Korea, but the figures were slightly lower than the 70-90% obtained elsewhere[12]. The ratio of males to females was 1.11:1. Compared to other results in which the male to female ratios were 1.7:1-2: 1, our result showed a higher proportion of female patients.

Some genetic abnormalities such as t(11:18)(q21:q21) have been discovered to be related with the process of MALT lymphoma formation by H pylori. t(11:18) existed in about 18-50% of MALT lymphomas. Liu et al.[13] reported that low grade MALT lymphoma with t(11:18) was more resistant to H pylori eradication regimens. Remstein et al.[14] reported that low grade MALT lymphoma without t(11:18) tended to have t(1:14) or to show aneuploidy. Moreover, abnormal manifestations of bcl-6, some trisomies (including trisomy 3), abnormality of P53, and hypermethylation of P15 or P16 are also thought to be related to the formation of MALT lymphoma. Thus, there might be several pathways to the formation of MALT lymphoma[15].

Cabras et al.[16] advocated multiple pathways to high grade transformation. The time taken for high grade transformation was estimated at about 10 years by Yoshino et al.[17], which was not definite with our study. On the other hand, there were 4 cases in our study who had been diagnosed as low grade MALT lymphoma by preoperative gastroscopy, and they were diagnosed as higher grade lymphoma after H pylori eradication or surgery. So, there is a possibility that high grade transformations were observed within a few months.

We could spare the time and cost of attempting to eradicate H pylori, if we knew the characteristics of the group whose diseases were resistant to H pylori eradication therapies and tended to transform to higher grades. Currently, t(11:18), H pylori with Cag A(+), invasion deeper than the submucosal layer by endoscopic ultrasonography, and lymph node metastasis have been reported to be risk factors of resistance[18]. However, in our series, all 5 patients whose lymphoma invaded the submucosal layer without lymph node metastasis failed H pylori eradication and underwent operation, demonstrating the need for further studies on the risk factors involved.

Misdiagnoses could be made in patients with higher grade MALT lymphoma or diffuse large B cell lymphoma once diagnosed as low grade MALT lymphoma preoperatively. Strecker et al.[19] reported that the accurate diagnostic rate with grade differentiation was 73% even in the large medical institutes because of the limitations of the small, partial biopsy samples produced by gastroscopic procedures. In our study also, 87% showed the same diagnosis and the same grade before and after operation.

Likewise, among the 19 patients once diagnosed as diffuse large B cell lymphoma preoperatively, 4(21.1%) were diagnosed as high grade MALT lymphoma because the portions of the classic features of low grade MALT lymphoma were found postoperatively. Even more, the histopathologic sections from postoperative specimens could miss the portions of the classic features of low grade MALT lymphoma which were present partly, too. This is the reason why we categorized both diffuse large B cell lymphoma and high grade MALT lymphoma patients into one group.

Eck et al.[20] proposed complementary serology testing to confirm the relationship with H pylori, because positive results by serologic tests are obtained even in H pylori-negative patients by gastroscopic biopsy. We checked 4 cases in which serology testing was performed. Three patients were also positive by biopsy, but one patient had a positive serologic result despite a negative finding by gastroscopic biopsy.

Recently, some have suggested non-operative methods such as H pylori eradication, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy as the primary therapeutic strategies instead of surgery[21,22]. Whereas in our study only 3 patients with remnant tumor in the resection margin undertook radiotherapy, Schecheter et al.[23] reported the complete resolution of 17 cases of MALT lymphomas in stages I and II with radiotherapy. The German multicenter study GIT NHL 01/92 in 2001 reported no significant difference in the survival or recurrence rates between 79 patients who had surgery alone or surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy and 106 patients who had chemotherapy alone[24].

Investigators who suggested that chemotherapy was the primary strategy believed that there was no difference in the survival rates of surgical resection and chemotherapy, and that those who did not receive radical resection showed significant lower survival rates, and that chemotherapy can reduce the size of a lesion and make the surgery easier, even when it failed to effect a complete cure.

On the other hand, surgical resection as the primary therapy allowed the accurate staging of the lymphoma. Besides, in those patients with serious complications such as perforation and bleeding, surgical procedure became more difficult due to the fragile gastric wall, and the higher risk of postoperative complications. Moreover, peritoneal seeding could theoretically occur via the perforated gastric wall[1-3,25].

We found that the proportion of patients with multiple lesions was 19.3%. In addition, cases in which the MALT lymphoma had spread along the mucosal layer to the esophagus or the duodenum were also reported. In the H pylori infected stomach, it is well known that gastric mucosa other than MALT lymphoma lesions, may have B cell monoclonality. Even after H pylori eradication therapy, it has been reported that about 50% of patients had B cell monoclonality in their gastric mucosa[26,27]. It is not certain that this B cell monoclonality reflects the presence of a remnant or pre-malignant lesion. But if B cell monoclonality is a true pre-malignant lesion, we would rather perform total gastrectomy to completely remove possible malignant lesions.

In the clinical setting, some debates exist about the results of subtotal and total gastrectomies. Kodera et al.[28] showed that there was no difference in the survival rates of 45 patients with subtotal gastrectomy and 37 patients with total gastrectomy among 82 patients with primary gastric lymphoma in stages I and II. Similar results were reported by Rodriguez-Sanjuan et al.[29], and by Colucci et al.[30]. Bozer et al. [31] reported better survival rates in 13 patients with stages I and II primary gastric lymphoma who received total gastrectomy than in 24 patients who underwent subtotal gastrectomy. However, they mentioned the possibility of more complete lymph node dissection in the total gastrectomy group.

In the past, concurrent splenectomy and multiple lymph node biopsies were recommended for staging. But, the local spreading characteristics of primary gastric lymphoma make the splenectomy unnecessary if the spleen is not invaded. These characteristics sometimes make it reasonable to use the TNM staging systems instead of Ann-Arbor staging. There are some controversies on the necessity of multiple intraoperative lymph node biopsy. Chang et al.[32] reported that about 40% of low grade lymphomas limited within the submucosal layer had lymph node metastasis. Our series also had 2 low grade lymphoma patients with lymph node metastasis, and 2 of HG group who had no lymph node metastasis (stage Ie) recurred in the intraabdominal lymph nodes. Only 1 patient among those with recurred diseases had recurred lesions in the remnant stomach, and the majority of them had their recurred lesions in lymph nodes. So, wide lymph node dissection must be performed, and additional biopsy for suspicious lymph nodes is recommended.

Therefore, subtotal gastrectomy can be performed safely with sufficient lymph node dissection, but sufficient preoperative searching for multiple lesions by gastroscopy or endoscopic ultrasonography is required, and close postoperative follow-up should be emphasized.

We could not found a definite relationship between the stages and the disease-free-survival rate, because of the small size of the objectives and a high proportion of recurred patients with lymph node negative lymphoma. One of them having a 13 cm×10 cm lymphoma directly invading colon and pancreas was classified as Musshoff stage Ie, and contributed to a high proportion of stage Ie patients in all recurred ones. All the recurred patients in stage-Ie were of HG group and none of LG group had recurred, even though it showed no significant differences. Most of them underwent sufficient lymph node dissection (D2), and the number of dissected lymph nodes was 64, 60, 19, 11, respectively. It implies that high grade lymphoma is more aggressive and has a greater possibility of systemic features than low grade lymphoma, even in early stage.

In conclusion, the majority of patients with low grade MALT lymphoma had early stage disease, which is curable by surgery only. The proportions of advanced diseases that need additional chemotherapy, and the proportions of recurred patients were lower in the LG group than in the HG group. The risk factors of recurrence were pathologic grade and TNM stage. Among the patients with recurred lymphoma, the number of patients who had subtotal gastrectomy was somewhat greater than the number of patients who had total gastrectomy, even though it was not significant. The existence of multiple lesions or lymph node metastasis even in low grade MALT lymphoma emphasizes the need for more thorough preoperative diagnosis, radical surgical resection with lymph node dissection, and careful postoperative follow-up.

Edited by Wang XL and Xu FM

| 1. | Vaillant JC, Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, Aegerter P, Gayet B, Rambaud JC, Valleur P, Parc R. Management and long-term re-sults of surgery for localized gastric lymphomas. Am J Surg. 2000;179:216-222. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bartlett DL, Karpeh MS Jr, Filippa DA, Brennan MF. Long-term follow-up after curative surgery for early gastric lymphoma. Ann Surg. 1996;223:53-62. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Salvagno L, Sorarù M, Busetto M, Puccetti C, Sava C, Endrizzi L, Giusto M, Aversa S, Chiarion Sileni V, Polico R. Gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: analysis of 252 patients from a multicenter study. Tumori. 1999;85:113-121. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Morgner A, Miehlke S, Stolte M, Neubauer A, Alpen B, Thiede C, Klann H, Hierlmeier FX, Ell C, Ehninger G. Development of early gastric cancer 4 and 5 years after complete remission of Helicobacter pylori associated gastric low grade marginal zone B cell lymphoma of MALT type. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:248-253. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, Flandrin G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Vardiman J, Lister TA, Bloomfield CD. The World Health Orga-nization classification of neoplasms of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting—Airlie House, Virginia, November, 1997. Hematol J. 2000;1:53-66. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Isaacson P, Wright DH. Malignanat lymphoma of mucosa-asso-ciated lymphoid tissue. A distinctive type of B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 1983;52:1410-1416. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Cheng H, Wang J, Zhang CS, Yan PS, Zhang XH, Hu PZ, Ma FC. Clinicopathologic study of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma in gastroscopic biopsy. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1270-1272. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Zhou Q, Xu TR, Fan QH, Zhen ZX. Clinicopathologic study of primary intestinal B cell malignant lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:538-540. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Xue FB, Xu YY, Wan Y, Pan BR, Ren J, Fan DM. Association of H. pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a Meta analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:801-804. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E, Morgner A, Alpen B, Wündisch T, Thiede C, Neubauer A. Helicobacter and gastric MALT lymphoma. Gut. 2002;50 Suppl 3:III19-III24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Paik KY, Noh JH, Heo JS, Sohn TS, Choi SH, Joh , JW , Kim S, Kim YI. Clinical analysis of MALT lymphoma in the stomach. J Ko-rean Surg Soc. 2002;62:468-471. |

| 12. | Nakamura S, Yao T, Aoyagi K, Lida M, Fujishima M, Tsuneyoshi M. Helicobacter pylori and primary gastric lymphoma. A histo-pathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 237 patients. Cancer. 1997;79:3-11. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Liu H, Ruskon-Fourmestraux A, De Jong D, Pileri S, Thiede C, Lavergne A, Boot H, Caletti G, Wundisch T, Molina T. T(11;18) is a marker for all stage gastric MALT lymphomas that will not respond to H pylori eradication. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1286-1294. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Remstein ED, Kurtin PJ, James CD, Wang XY, Meyer RG, Dewald GW. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas with t(11; 18)(q21;q21) and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas with aneuploidy develop along different pathogenetic pathways. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:63-71. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Du MQ, Isaacson PG. Gastric MALT lymphoma: from aetiology to treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:97-104. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cabras AD, Weirich G, fend F, Nahrig J, Bordi C, Hofler H, Werner M. Oligoclonality of a “composite” gastric difuse large B- cell lymphoma with area of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue typr. Virchows Arch. 2002;440:209-214. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yoshino T, Omonishi K, Kobayashi K, Mannami T, Okada H, Mizuno M, Yamadori I, Kondo E, Akagi T. Clinicopathological features of gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas: high grade transformation and comparison with diffuse large B cell lymphomas without MALT lymphoma features. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:187-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, Lavergne A, Aegerter PH, Megraud F, Palazzo L, de Mascarel A. Predictive factors of regression of gastric MALT lymphoma after anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment. Gut. 2001;48:290-292. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Strecker P, Eck M, Greiner A, Kolve M, Schmausser B, Marx A, Fischbach W, Fellbaum C, Müller-Hermelink HK. [Diagnostic value of stomach biopsy in comparison with surgical specimen in gastric B-cell lymphomas of the MALT type]. Pathologe. 1998;19:209-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Eck M, Greiner A, Schmausser B, Eck H, Kolve M, Fischbach W, Strecker P, Müller-Hermelink HK. Evaluation of Helicobacter pylori in gastric MALT-type lymphoma: differences between histologic and serologic diagnosis. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:1148-1151. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Tondini C, Balzarotti M, Santoro A, Zanini M, Fornier M, Giardini R, Di Felice G, Bozzetti F, Bonadonna G. Initial chemotherapy for primary resectable large-cell lymphoma of the stomach. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:497-499. |

| 22. | Thieblemont C, Dumontet C, Bouafia F, Hequet O, Arnaud P, Espinouse D, Felman P, Berger F, Salles G, Coiffier B. Outcome in relation to treatment modalities in 48 patients with localized gastric MALT lymphoma: a retrospective study of patients treated during 1976-2001. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schechter NR, Portlock CS, Yahalom J. Treatment of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the stomach with radiation alone. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1916-1921. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: II. Combined surgical and conservative or conservative management only in localized gastric lymphoma--results of the prospective German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3874-3883. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kodera Y, Yamamura Y, Nakamura S, Shimizu Y, Torii A, Hirai T, Yasui K, Morimoto T, Kato T, Kito T. The role of radical gastrectomy with systematic lymphadenectomy for the diagnosis and treatment of primary gastric lymphoma. Ann Surg. 1998;227:45-50. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Alpen B, Thiede C, Wundisch T, Bayerdorffer E, Stolte M, Neubauer A. Molecular diagnostics in low-grade gastric mar-ginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tis-sue type after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Clin Lym-phoma. 2001;2:103-108. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Thiede C, Wündisch T, Alpen B, Neubauer B, Morgner A, Schmitz M, Ehninger G, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E, Neubauer A. Long-term persistence of monoclonal B cells after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection and complete histologic remission in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1600-1609. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Kodera Y, Nakamura S, Yamamura Y, Shimizu Y, Torii A, Hirai T, Yasui K, Morimoto T, Kato T. Primary gastric B cell lymphoma: audit of 82 cases treated with surgery and classified according to the concept of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. World J Surg. 2000;24:857-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rodriguez-Sanjuan JC, Alvarez-Canas C, Casado F, Garcia-Castrillo L, Casanova D, Val-Bernal F, Naranjo A. Results and prognostic factors in stage I(E)-II(E) primary gastric lymphoma after gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:296-303. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Colucci G, Naglieri E, Maiello E, Marzullo F, Caruso ML, Leo S, Pellecchia A, Cramarossa A, Timurian A, Prete F. Role of prognostic factors in the therapeutic strategy of primary gastric non Hodgkin's lymphomas. Clin Ter. 1998;149:25-30. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Bozer M, Eroglu A, Ünal E, Eryavuz Y, Kocaoglu K, Demirci S. Survival after curative resection for stage IE and IIE primary gas-tric lymphoma. Hepatogastoenterol. 2001;48:1202-1205. |

| 32. | Chang DK, Chin YJ, Kim JS, Jung HC, Kim CW, Song IS, Kim CY. Lymph node involvement rate in low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma—too high to be neglected. Hepatogastroenterol. 1999;46:2694-2700. |