Published online Feb 1, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i3.309

Revised: January 4, 2004

Accepted: January 11, 2004

Published online: February 1, 2004

Historically, mast cells were known as a key cell type involved in type I hypersensitivity. Until last two decades, this cell type was recognized to be widely involved in a number of non-allergic diseases including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Markedly increased numbers of mast cells were observed in the mucosa of the ileum and colon of patients with IBD, which was accompanied by great changes of the content in mast cells such as dramatically increased expression of TNF-α, IL-16 and substance P. The evidence of mast cell degranulation was found in the wall of intestine from patients with IBD with immunohistochemistry technique. The highly elevated histamine and tryptase levels were detected in mucosa of patients with IBD, strongly suggesting that mast cell degranulation is involved in the pathogenesis of IBD. However, little is known of the actions of histamine, tryptase, chymase and carboxypeptidase in IBD. Over the last decade, heparin has been used to treat IBD in clinical practice. The low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) was effective as adjuvant therapy, and the patients showed good clinical and laboratory response with no serious adverse effects. The roles of PGD2, LTC4, PAF and mast cell cytokines in IBD were also discussed. Recently, a series of experiments with dispersed colon mast cells suggested there should be at least two pathways in man for mast cells to amplify their own activation-degranulation signals in an autocrine or paracrine manner. The hypothesis is that mast cell secretogogues induce mast cell degranulation, release histamine, then stimulate the adjacent mast cells or positively feedback to further stimulate its host mast cells through H1 receptor. Whereas released tryptase acts similarly to histamine, but activates mast cells through its receptor PAR-2. The connections between current anti-IBD therapies or potential therapies for IBD with mast cells were discussed, implicating further that mast cell is a key cell type that is involved in the pathogenesis of IBD. In conclusion, while pathogenesis of IBD remains unclear, the key role of mast cells in this group of diseases demonstrated in the current review implicates strongly that IBD is a mast cell associated disease. Therefore, close attentions should be paid to the role of mast cells in IBD.

- Citation: He SH. Key role of mast cells and their major secretory products in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(3): 309-318

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i3/309.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i3.309

Historically, mast cells were known as a key cell type involved in type I hypersensitivity[1]. Until last two decades, this cell type was recognized to be widely involved in a number of non-allergic diseases in internal medicine including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, liver cirrhosis, cardiomyopathy, multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, etc. (Table 1). This article will focus solely on the relationships between mast cells and inflammatory bowel disease, give evidence for a hypothesis of self-amplification mechanism of mast cell degranulation in gut and discuss the potential therapies for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

| Disease | Evidence |

| Chronic obstructive | Mast cell hyperplasia in epithelia and |

| pulmonary disease | bronchial glands[2,3], tryptase and histamine |

| (COPD) | release in BALF[4] |

| Cor pulmonale | Mast cell hyperplasia in bronchial and |

| vascular tissues[5] | |

| Bronchiectasis | Increased numbers of degranulated mast |

| cells in lung tissue, and higher tryptase | |

| concentrations in BALF[6] | |

| Acute respiratory | Mast cell hyperplasia[7] and degranulation[8] |

| distress syndrome (ARDS) | |

| ronchiolitis obliterans- | Mast cell hyperplasia[9] and degranulation[10] |

| organizing pneumonia | |

| Cystic fibrosis | Mast cell hyperplasia[11] and |

| degranulation[12] in lung | |

| Interstitial lung diseases | Mast cell hyperplasia[13] and degranulation[14] |

| Silicosis | Mast cell hyperplasia[15] |

| Sarcoidosis | Mast cell hyperplasia[16], and |

| degranulation[17] in lung | |

| Lung cancer | Mast cell hyperplasia[18] |

| Tuberculosis | Mast cell degranulation[19] |

| Gastritis | Mast cell hyperplasia[20] and degranulation[21] |

| Peptic ulcer | Mast cell hyperplasia[22] and degranulation[23] |

| Hepatocellular | Mast cell hyperplasia[24] |

| carcinoma | |

| Ulcerative colitis | Mast cell hyperplasia[25,26] and degranulation[27] |

| Crohn’s disease | Mast cell hyperplasia[28] and degranulation[29] |

| Liver cirrhosis | Mast cell hyperplasia[30] |

| Hepatitis | Mast cell hyperplasia[31,32] |

| Pancreatitis | Mast cell hyperplasia and degranulation[33] |

| Atherosclerosis | Mast cell hyperplasia[34] |

| Myocardial infarction | Mast cell hyperplasia and degranulation[35,36] |

| Congenital heart disease | Mast cell hyperplasia and subtype change[37] |

| Myocarditis | Mast cell hyperplasia[38] |

| Cardiomyopathy | Mast cell hyperplasia[39] and degranulation[40] |

| Diabetes | Mast cell hyperplasia[41] |

| Thyroiditis | Mast cell hyperplasia[42] |

| Osteoporosis | Mast cell hyperplasia[43] |

| Glomerulonephritis | Mast cell hyperplasia[44] |

| Nephropathy | Mast cell hyperplasia[45] |

| Multiple sclerosis | Mast cell hyperplasia[46] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Mast cell degranulation[47] |

| Osteoarthritis | Mast cell hyperplasia[48] |

| Rheumatic arthritis | Mast cell hyperplasia[49] |

Mast cell is the cell that contains numerous metachromatically stained basophilic granules in its cytoplasm. It has various sizes between species with diameters of up to 30 µm reported in humans, and from 3.5 µm to 22 µm in rodents[28,50]. In human lung, for example, the range of mast cell diameters has been reported to be between 9.9 µm and 18.4 µm[51] and in human skin between 4 µm and 18 µm[52]. The shape of mast cell varies as well, it has been described as polyhedral, fusiform, ovoid, and rectangular, and appears dependent on tissue locations. Mast cell nuclei are usually round or oval and have peripherally dispersed heterochromatin[53].

Up to 40% of the volume of mast cell is occupied by membrane-enclosed secretory granules[54]. There are 50 to 500 secretory granules in one mature human mast cell, each with a diameter ranging from 0.2 to 0.5 µm. Within a given mast cell, these granules are usually of a uniform size, but there is variability from cell to cell[55]. Mast cell granules originate from the Golgi apparatus, which is responsible for the synthesis and organization of the preformed mediators contained therein[56].

Upon activation mast cell can release its mediators to fulfill its biological functions. Among preformed mediators, histamine is a primary amine synthesized from histidine in the Golgi apparatus, from where it is transported to the granule for storage in ionic association with the acidic residues of glycosaminoglycans side chains of heparin and proteinases[57,58]. The histamine content of mast cells dispersed from human lung and skin is similar at 2 to 5 pg/cell, and the stored histamine ranges from 10 to 12 µg/g in both tissues[53]. As only mast cell and basophil contain histamine in man, and few basophils in human tissue histamine can be used as a marker of mast cell degranulation.

Proteoglycans in human mast cells include heparin and chondroitin sulphate, which contains several highly sulphated glycosaminoglycan side chains attached to a single chain protein core. They comprise the major supporting matrix of the mast cell granule with the sulphate groups binding to histamine, proteinases and acid hydrolases.

Neutral proteases of mast cells are also preformed mediators. Three mast cell unique neutral proteinases (tryptase, chymase and carboxypeptidase) have been isolated in man and there is evidence also for a proteinase with antigenic and enzymatic properties similar to those of neutrophil cathepsin G in mast cells[59,60]. Mast cell tryptase, chymase and carboxypeptidase are reliable markers of mast cell degranulation. Based on their content of proteinases, mast cells can be classified into two types in man, with MCT cells defined as those containing tryptase but not chymase, and MCTC cells as those containing both tryptase and chymase[61]. Subsequently both carboxypeptidase[62] and cathepsin G like proteases[63,64] have been found to be localised exclusively in the MCTC population.

Newly generated mediators include eicosanoids and platelet activating factor (PAF). Eicosanoids are a group of newly generated mediators of mast cells. Immunological activation of mast cells results in the liberation of arachidonic acid from phospholipids in the cell membrane. This 20-carbon fatty acid is then rapidly oxidized along either of two independent pathways, namely the cyclooxygenase pathway to form PGD2 and the lipoxygenase pathway to form LTC4. These are the only two eicosanoids produced by human mast cells[65]. PAF is also a product of phospholipid metabolism in mast cells.

Mast cell cytokines may constitute a third category in that they may be both preformed and newly synthesized. For instance, it has been reported that approximately 75%, 10%, 35%, and 35% of mast cells contain IL-4, IL-5, IL-6 and TNF-α, respectively in the nasal mucosa and bronchus[66]. Mast cell contains also IL-1β, IL-3, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-13, IL-16, IL-18, IL-25, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), stem cell factor macrophage chemotactic peptide (MCP)-1, 3, 4, regulated on activation of normal T cell-expressed and secreted protein (RANTES) and eotaxin[67].

Mast cell activation is a crucial step in mast cell involved events because it seems that only activated mast cells are able to cause pathophysiological changes. There are a number of compounds that can activate mast cells. They are antigens, anti-IgE and ionophores. Skin mast cells but not those of lung, tonsil or gut can be activated by other diverse compounds including substance P, VIP, C5a and C3a, somatostatin, compound 48/80, morphine, pepstatin, MBP, PAF, platelet factor 4 and very-low-density lipoproteins[68,53]. Stem cell factor[69], eosinophil cationic protein[70] and tryptase[71] have also been found to be able to activate human mast cells.

The mechanisms of mast cell activation differ with different classes of triggers. Human skin mast cells are able to respond to non-crosslinking stimuli, such as neuropeptides, morphine, and complement fragments[68]. IgE-dependent mast cell activation is a complicated process. It involves a specific IgE bound to its high affinity receptor (FcεR1) on the surface of mast cells, a multivalent antigen (Ag) crosslinking specific IgEs bound to FceR1 and a signal transduction and translation process in mast cells.

While normal human mast cell line is not available, dispersed and purified mast cells are essential for investigating mast cell functions. Human mast cells have been dispersed from skin, lung, tonsil, synovium heart and intestine tissues by incubation with collagenase and hyaluronidase. These dispersed cells have appreciable morphological and functional properties of mast cells. Since dispersed cells can be evenly distributed in experiment, it is the most popular method at present. However, the purity of mast cells with this system is only 0.5% - 10% depending on tissues.

Chopped tissue fragments were also used for mast cell degranulation study. We found that it was difficult to evenly distribute cells in tissue fragments, therefore causing large experimental errors.

Laboratory animal tissues or mast cells are widely used in mast cell degranulation study. Thus, rat and mouse peritoneum, guinea pig lung and cultured mouse bone marrow derived mast cells are the most popular models. However, it is always adequate to use human mast cells to investigate the pathophysiological process of human disease.

As early as in 1980, Dvorak and colleagues[28] reported that the number of mast cells was markedly increased in the involved area of the ileum of patients with Crohn’s disease. In 1990, Nolte et al[72]. found that the mast cell count in patients with ulcerative colitis was increased compared with that in control subjects and patients with Crohn’s disease. In an individual patient, the mast cell count obtained from inflamed tissue was greater than that of normal tissue. This finding was taken further by King et al[26]. in 1992 that the number of mast cells in active ulcerative colitis was 6.3 in active inflammation, 19.5 at the line of demarcation and 15.8 in normal mucosa. The accumulation of mast cells at the visible line of demarcation between normal and abnormal mucosa suggested that mast cells played a crucial role in the pathogenesis of the disease, either causing further damage or limiting the expansion of damage. Recently, a report[73] provided us an even more convincing evidence and clear picture on the elevated number of mast cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Nishida and colleagues found that there were greater numbers of mast cells than macrophages in the lamina propria of patients with inflammatory bowel disease though this was not found in patients with collagenous colitis. Interestingly, increased numbers of mast cells were observed throughout the lamina propria, particularly in the upper part of lamina propria, whereas increased numbers of macrophages were only seen in the lower part of lamina propria in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. This could result from that accumulated mast cells released their proinflammatory mediators, and these mediators, at least tryptase[74] and chymase[75], induced macrophage accumulation in the lower part of lamina propria. Dramatically increased numbers of mast cells were also observed in the hypertrophied and fibrotic muscularis propria of strictures in Crohn’s disease compared with normal bowel (81.3/mm2vs 1.5/mm2)[76].

Not only the number of mast cells was elevated[77], but also the contents of mast cells were greatly changed in inflammatory bowel disease in comparison with normal subjects. Laminin, a multi-functional non-collagenous glycoprotein, which is normally found in extracellular matrix was detected in mast cells in muscularis propria (but not those in submucosa), indicating that mast cells may be actively involved in the tissue remodeling in Crohn’s disease[76]. Similarly, the number of TNF-α positive mast cells was greater in the muscularis propria of patients with Crohn’s disease than that in normal controls[78]. In the submucosa of involved ileal wall of Crohn’s disease, more TNF-α positive mast cells were found in inflamed area than uninflamed area. Since those TNF-α positive mast cells were mail cell type that expressed TNF-α in ileal wall, the successful treatment of Crohn’s disease with anti-TNF-α antibody could well be the consequence that the antibody neutralized the excessively secreted TNF-α from mast cells. This indirectly proved the important contribution of mast cells to the development of Crohn’s disease. Increased number of IL-16 positive mast cells, which was correlated well with increased number of CD4+ lymphocytes, was also observed in active Crohn’s disease[79], indicating that this chemokine may selectively attract CD4+ lymphocytes to the involved inflammatory area[80,81]. In chronic ulcerative colitis, increased number of substance P positive mast cells was observed in gut wall, particularly in mucosa[82], indicating the possibility of neuronal elements being involved in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Increased number of mast cells was also seen in a number of diseases closely related to inflammatory bowel disease. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic sclerosing sialadenitis showed similar marked mast cell infiltration pattern with inflammatory bowel disease[83]. Focal active gastritis is a typical pathological change in Crohn’s disease[84], in which large number of mast cells accumulate at the border of the lesions[20]. In the animal models, increased number of mast cells in gastrointestinal tract was observed in dogs with inflammatory bowel disease in comparison with healthy dogs[85]. When given 3% dextran sulphate sodium for 10 days[86] or water avoidance stress for 5 days[87], pathological changes such as mucosal damage and edema were developed in rats, and these were accompanied by mast cell hyperplasia and activation. However, the same treatment had little effect on mast cell deficient Ws/Ws rats, implying the importance of mast cells in the development of inflammatory bowel disease.

As early as in 1975, Lloyd and colleagues observed that there were marked degranulation of mast cells and IgE-containing cells in the bowel wall of patients with Crohn’s disease[29], and this observation later became an important investigation area for understanding the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. In 1980, Dvorak et al[28]. described in more detail the degranulation of mast cells in the ileum of patients with Crohn’s disease with transmission electron microscopy technique. Similarly, with electron microscopy technique, degranulation of mast cells was seen in the intestinal biopsies of patients with ulcerative colitis[88]. Using immunohistochemistry technique with antibodies specific to human tryptase or chymase, both of which are exclusive antigens of human mast cells, mast cell degranulation was found in the mucosa of bowel walls of patients with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis[89] and chronic inflammatory duodenal bowel disorders[90].

Using segmental jejunal perfusion system with a two-balloon, six channel small tube, Knutson and colleagues found that the histamine secretion rate was increased in patients with Crohn’s disease compared with normal controls, and the secretion of histamine was related to the disease activity, indicating strongly that degranulation of mast cells was involved in active Crohn’s disease[91]. The highly elevated mucosal histamine levels were also observed in patients with allergic enteropathy and ulcerative colitis[27]. Moreover, enhanced histamine metabolism was found in patients with collagenous colitis and food allergy[92], and increased level of N-methylhistamine, a stable metabolite of the mast cell mediator histamine, was detected in the urine of patients with active Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis[93,94]. Since increased level of N-methylhistamine was significantly correlated to clinical disease activity, the above finding further strongly suggested the active involvement of histamine in the pathogenesis of these diseases.

Interestingly, mast cells originated from the resected colon of patients with active Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis were able to release more histamine than those from normal colon when being stimulated with an antigen, colon derived murine epithelial cell associated compounds[95]. Similarly, cultured colonrectal endoscopic samples from patients with IBD secreted more histamine towards substance P alone or substance P with anti-IgE than the samples from normal control subjects under the same stimulation[96]. In a guinea pig model of intestinal inflammation induced by cow’s milk proteins and trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid, both IgE titers and histamine levels were higher than normal control animals[97].

As a proinflammatory mediator, histamine is selectively located in the granules of human mast cells and basophils and released from these cells upon degranulation. To date, a total of four histamine receptors H1, H2, H3 and H4 have been discovered[98] and the first three of them have been located in human gut[99,100], proving that there are some specific targets on which histamine can work in intestinal tract. Histamine was found to cause a transient concentration-dependent increase in short-circuit current, a measure of total ion transport across the epithelial tissue in gut[101]. This could be due to the interaction of histamine with H1-receptors that increased Na and Cl ions secretion from epithelium[102]. The finding that H1-receptor antagonist pyrilamine was able to inhibit anti-IgE induced histamine release and ion transport[103] suggests further that histamine is a crucial mediator responsible for diarrhea in IBD and food allergy. The ability of SR140333, a potent NK1 antagonist in reducing mucosal ion transport was most likely due to its inhibitory actions on histamine release from colon mast cells[104].

Tryptase is a tetrameric serine proteinase that constitutes some 20% of the total protein within human mast cells and is stored almost exclusively in the secretory granules of mast cells[105] in a catalytically active form[106]. The ability of tryptase to induce microvascular leakage in the skin of guinea pig[107], to accumulate inflammatory cells in the peritoneum of mouse[74] and to stimulate release of IL-8 from epithelial cells[108], and the evidence that relatively higher secretion of tryptase has been detected in ulcerative colitis[109] implicated that this mediator is involved in the pathogenesis of intestinal diseases. However, little is known about its actions in IBD. Recently, proteinase activated receptor (PAR)-2, a highly expressed receptor in human intestine[110] was recognized as a receptor of human mast cell tryptase[111]. Colonic administration of PAR-2 agonists up-regulated PAR-2 expression, induced granulocyte infiltration, colon wall edema and damage and stimulated an increased paracellular permeability of colon mucosa[112]. PAR-2 agonists were also able to stimulate intestinal electrolyte secretion[113]. Interestingly, some 60% and 46% of mast cells in ulcerative colitis tissues expressed PAR-2 or TNF-α, respectively. PAR-2 agonists were able to stimulate TNF-α secretion from mast cells[114] and secreted TNF-α could then enhance PAR-2 expression in a positive feedback manner[113]. These findings indicated further the importance of TNF-α and mast cells in the pathogenesis of IBD.

Chymase is a serine proteinase exclusively located in the same granules as tryptase and could be released from granules together with other preformed mediators. Large quantity of active form chymase (10 pg per mast cell) in mast cells[115] implicates that this mast cell unique mediator may play a role in mast cell related diseases. Indeed, chymase has been found to be able to induce microvascular leakage in the skin of guinea pig[116], stimulate inflammatory cell accumulation in peritoneum of mouse[75], and alter epithelial cell monolayer permeability in vitro[117]. However, little is known about its actions in IBD. Mast cell carboxypeptidase is a unique product of MCTC subtype mast cells. There is some 10 pg in each mast cells. No information about the relationship between mast cell carboxypeptidase and IBD is available, but the successful coloning of mast cell carboxypeptidase from human gut tissue and obtaining of recombinant human mast cell carboxypeptidase [chen 2004] will certainly help to initiate the investigation of the role of mast cell carboxypeptidase in IBD. It is astonished to learn the fact that the potential roles of mast cell neutral proteinases in IBD have been almost completely ignored till today. Since they are the most abundant granule products of mast cells and have been demonstrated to possess important actions in inflammation, they should certainly contribute to the occurrence and development of IBD.

Over the last decade, heparin, a unique product of human mast cells and basophils, has been used to treat IBD in clinical practice. Using combined heparin and sulfasalazine therapy, Gaffney and colleagues successfully treated 10 patients with ulcerative colitis poorly controlled on sulfasalazine and prednisolone[119]. Similarly, Evans et al[120]. found that heparin was effective in treating corticosteroid-resistant ulcerative colitis, and Yoshikane et al[121]. reported that heparin was very effective in the treatment of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) caused by ulcerative colitis. Recently, heparin was even suggested as a first line therapy in the treatment of severe colonic inflammatory bowel disease[122], but should be administered in hospitalized patients only because of the risk of possible serious bleeding[123]. To overcome bleeding side effect, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) was employed as adjuvant therapy[124], and the patients showed good clinical and laboratory response with no severe adverse effects[125,126].

Apart from anticoagulation activity, the mechanisms by which heparin was able to treat IBD were considered to include its ability to inhibit the recruitment of neutrophils, reduce production of pro-inflammatory cytokines[127] and restore the high-affinity receptor binding of antiulcerogenic growth factor[128,129]. The ability of heparin to inhibit neutrophil activation, adhesion, and chemotaxis was also found in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disorder[130,131], suggesting that balanced interactions between mast cells and neutrophils might be important for the development of IBD. In rat models of IBD, heparin revealed its ability to attenuate TNF-α induced leucocyte rolling and CD11b dependent adhesion[132], reduce serum IL-6 level and improve microcirculatory disturbance in rectal walls[133,134]. Thus, preformed mast cell mediators seemed to have dual actions on the pathogenesis of IBD. On the one hand, tryptase, histamine, and TNF-α can cause damage in the intestinal wall, and on the other hand, heparin can protect the intestinal wall from damage.

It was reported that mast cells in the actively involved areas of ulcerative colitis released greater amount of PGD2, in parallel to histamine and LTC4[135]. In a rat experimental colitis model, the time for stimulating PGD2 release was initiated within 1 h and increased 4 fold within 3 h[136]. This was accompanied by a significant granulocyte infiltration, indicating the likelihood of involvement of PGD2 in IBD. The basal release of LTC4 was enhanced in the gut of Crohn’s disease patients[137], but the meaning of this enhancement still remains uninvestigated.

It was found that mast cell activators, calcium ionophore A23187 and anti-IgE, were able to stimulate more PAF release from colon with ulcerative colitis than from normal colon, and this increased PAF release could be inhibited by steroids and 5-aminosalicylic acid[138,139]. The increased secretion of PAF was detected in the stool of patients with active Crohn’s disease, but not in that of patients with irritable bowel syndrome[140]. The level of PAF was also higher in colonic mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease than in colonic mucosa of healthy controls[141]. These indicated that PAF might be involved in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease[142]. The elevated level of PAF in colon was likely to be the result of increased production by colonic epithelial cells[143], lamina propria mononuclear cells[144] and mast cells, and decreased PAF acetylhydrolase (the major PAF degradation enzyme activity)[145]. In patients with ulcerative colitis, colonic production of PAF was increased in comparison with control patients[146], and the level of PAF in the stool of patients with ulcerative colitis was much higher than that in the stool of healthy volunteers[147]. Since increased colonic production of PAF was correlated to local injury and inflammation[146], it implicats strongly that PAF is involved in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. However, a randomized controlled trial with a specific PAF antagonist SR27417A showed that this compound had no significant effect on patients with active ulcerative colitis though it was safe in humans[148].

Dozens of proinflammatory cytokines were reported to be involved in the pathogenesis of IBD, but only several of them have been considered to be therapeutic targets. TNF-α was considered being secreted mainly from intestinal mast cells in IBD[78], and bacteria and anti-IgE were able to substantially enhance their release from mast cells[149]. The released mast cell products TNF-α and histamine could then synergistically stimulate ion secretion from intestinal epithelium[150]. The anti-TNF-α therapy will be described below. In IBD, most intestinal mast cells produce IL-3, and this increased expression of IL-3 could be inhibited by administration of steroid[151]. IL-10, a cytokine which can be produced by human mast cells[152], was reported to have some anti-inflammatory role in IBD[153]. However, the results from clinical trials were heterogeneous[154]. IL-1 was found to be excessively released from patients with ulcerative colitis and could stimulate the short-circuit current response to IL-1[155]. As for IL-3, steroid could significantly inhibit IL-1 release in IBD[156]. Mast cells from healthy controls did not produce IL-5, but mast cells from patients with intestinal inflammatory disease could release a relatively large amount of IL-5[157]. However, the effect of IL-5 on IBD needs to be investigated. It is still in early days to understand the role of cytokines in IBD, therefore it is difficult to draw a conclusive line on the issue whether cytokine related therapy is beneficial for IBD.

Tryptase has been proved to be a unique marker of mast cell degranulation in vitro as it is more selective than histamine to mast cells. Inhibitors of tryptase[71,158] and chymase[159] have been discovered to possess the ability to inhibit histamine or tryptase release from human skin, tonsil, synovial[160] and colon mast cells[161,162], suggesting that they are likely to be developed as a novel class of mast cell stabilizers. Recently, a series of experiments with dispersed colon mast cells suggested there should be at least two pathways in man for mast cells to amplify their own activation-degranulation signals in an autocrine or paracrine manner, which may partially explain the phenomena that when a sensitized individual contacts allergen only once the local allergic response in the involved tissue or organ may last for days or weeks. These findings included both anti-IgE and calcium ionophore were able to induce significant release of tryptase and histamine from colon mast cells[163], histamine was a potent activator of human colon mast cells[164] and the agonists of PAR-2 and trypsin were potent secretagogues of human colon mast cells[165]. Since tryptase was reported to be able to activate human mast cells[71] and H1 receptor antagonists terfenadine and cetirizine[166] were capable of inhibiting mast cell activation, the hypothesis of mast cell degranulation self-amplification mechanisms is that mast cell secretogogues induce mast cell degranulation, release histamine, then stimulate the adjacent mast cells or positively feedback to further stimulate its host mast cells through H1 receptor, whereas released tryptase acts similarly to histamine through its receptor PAR-2 on mast cells (Figure 1).

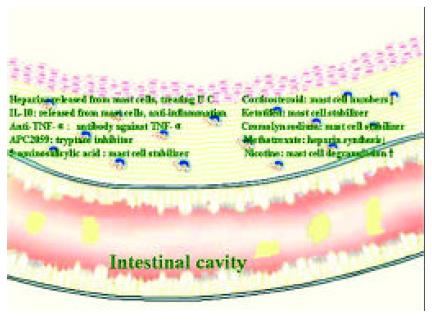

Although aminosalicylates and corticosteroids remain the mainstream therapeutic drugs for the treatment of IBD[167], the mast cell related therapy should be given some close attentions. Besides heparin therapy mentioned above, anti- TNF-α monoclonal antibody[168,169], infliximab in particular[170] showed promising results in treating Crohn’s disease. Thalidomide, an agent with antiangiogenic and immunomodulatory properties[171], possessed inhibitory activity towards TNF-α[172] and was therapeutically effective in IBD[173]. Mast cell tryptase inhibitor APC2059 was also effective and safe in treating ulcerative colitis[174]. Even 5-aminosalicylic acid, an aminosalicylate drug was an effective inhibitor of anti-IgE induced histamine and PGD2 release from human intestinal mast cells[175]. Thus the beneficial effects of 5-aminosalicylic acid on IBD were at least partially due to its mast cell stabilizing activity. Similarly, the effective treatment of IBD by corticosteroids might also be partially associated with its action on mast cells as significantly reduced numbers of mast cells were observed in the colon throughout steroid therapy[176].

The ineffective treatment of ulcerative colitis by mast cell stabilizer, cromolyn sodium[177] was most likely due to the drug that did not affect release of histamine from colon mast cells[178]. However, it was recently found to be effective in treating chronic or recurrent enterocolitis in patients with Hirschsprung’s disease[179]. In 1992, Eliakim and colleagues found that ketotifen, a mast cell stabilizer, was able to significantly decrease mucosal damage of ulcerative colitis in an experimental colitis model[180] and inhibit accumulation of PGE2, ITB4 and LTC4 in ulcerative colitis colon mucosa organ-culture[181], suggesting that this anti-asthma drug may be useful for the treatment of IBD. Indeed, ketotifen was revealed to be effective in treating IBD with 5-aminosalicylate intolerance[182], and acute ulcerative colitis in children[183], most likely through inhibition of mast cell and neutrophil degranulation[184].

It was surprising to learn that even immunomodulatory drug methotrexate, which showed promise in Crohn’s disease therapy[185] was able to inhibit heparin synthesis in mast cells[186], suggesting that the beneficial action of methotrexate on Crohn’s disease might be due to the reduction of heparin secretion from mast cells. Nicotine, an addictive component of tobacco, had a dual effect on IBD. It could ameliorate disease activity of ulcerative colitis but deteriorate disease process of Crohn’s disease[187]. Since nicotine was reported to be able to induce degranulation of mast cells[188], its dual action on IBD could be related to the locally imbalanced quantities of mast cell products, such as histamine and heparin. The association of these therapies with mast cells strongly indicates that mast cells are key cells in the development of IBD (Figure 2).

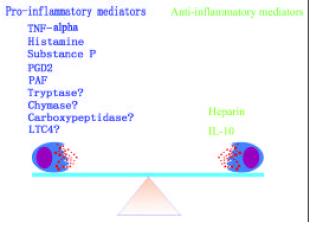

Mast cells are a key cell type, which is actively involved in the pathogenesis of IBD. The different actions of mast cell mediators in IBD suggest that there must be a balance between ‘pro-IBD’ and ‘anti-IBD’ mast cell mediators (Figure 3). Breaking this balance may cause diseases. There are at least two pathways, histamine pathway and tryptase pathway, for mast cells to amplify their degranulation signals. Each of them is likely to act in either autocrine or paracrine manner. These mast cell degranulation signal amplification mechanisms may be the key event in the pathophysiological process of long-lasting local response of mast cell associated diseases such as IBD, asthma and rhinitis.

Edited by Wang XL

| 1. | Walls AF, He SH, Buckley MG, McEuen AR. Roles of the mast cell and basophil in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy Review. 2001;1:68-72. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sun G, Stacey MA, Vittori E, Marini M, Bellini A, Kleimberg J, Mattoli S. Cellular and molecular characteristics of inflammation in chronic bronchitis. Eur J Clin Invest. 1998;28:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pesci A, Rossi GA, Bertorelli G, Aufiero A, Zanon P, Olivieri D. Mast cells in the airway lumen and bronchial mucosa of patients with chronic bronchitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:1311-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kalenderian R, Raju L, Roth W, Schwartz LB, Gruber B, Janoff A. Elevated histamine and tryptase levels in smokers' bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Do lung mast cells contribute to smokers' emphysema. Chest. 1988;94:119-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Daum S. [Pathophysiology of pulmonary hypertension and chronic cor pulmonale]. Z Gesamte Inn Med. 1993;48:525-531. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Sepper R, Konttinen YT, Kemppinen P, Sorsa T, Eklund KK. Mast cells in bronchiectasis. Ann Med. 1998;30:307-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liebler JM, Qu Z, Buckner B, Powers MR, Rosenbaum JT. Fibroproliferation and mast cells in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Thorax. 1998;53:823-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vucicevic Z, Suskovic T. Acute respiratory distress syndrome after aprotinin infusion. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:429-432. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Barbato A, Panizzolo C, D'Amore ES, La Rosa M, Saetta M. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) in a child with mild-to-moderate asthma: evidence of mast cell and eosinophil recruitment in lung specimens. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31:394-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pesci A, Majori M, Piccoli ML, Casalini A, Curti A, Franchini D, Gabrielli M. Mast cells in bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Mast cell hyperplasia and evidence for extracellular release of tryptase. Chest. 1996;110:383-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hubeau C, Puchelle E, Gaillard D. Distinct pattern of immune cell population in the lung of human fetuses with cystic fibrosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:524-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Henderson WR, Chi EY. Degranulation of cystic fibrosis nasal polyp mast cells. J Pathol. 1992;166:395-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pesci A, Bertorelli G, Gabrielli M, Olivieri D. Mast cells in fibrotic lung disorders. Chest. 1993;103:989-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hunt LW, Colby TV, Weiler DA, Sur S, Butterfield JH. Immunofluorescent staining for mast cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: quantification and evidence for extracellular release of mast cell tryptase. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67:941-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hamada H, Vallyathan V, Cool CD, Barker E, Inoue Y, Newman LS. Mast cell basic fibroblast growth factor in silicosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:2026-2034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Amano H, Kurosawa M, Ishikawa O, Chihara J, Miyachi Y. Mast cells in the cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis: their subtypes and the relationship to systemic manifestations. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24:60-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Flint KC, Leung KB, Hudspith BN, Brostoff J, Pearce FL, Geraint-James D, Johnson NM. Bronchoalveolar mast cells in sarcoidosis: increased numbers and accentuation of mediator release. Thorax. 1986;41:94-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nagata M, Shijubo N, Walls AF, Ichimiya S, Abe S, Sato N. Chymase-positive mast cells in small sized adenocarcinoma of the lung. Virchows Arch. 2003;443:565-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Muñoz S, Hernández-Pando R, Abraham SN, Enciso JA. Mast cell activation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: mediator release and role of CD48. J Immunol. 2003;170:5590-5596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Furusu H, Murase K, Nishida Y, Isomoto H, Takeshima F, Mizuta Y, Hewlett BR, Riddell RH, Kohno S. Accumulation of mast cells and macrophages in focal active gastritis of patients with Crohn's disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:639-643. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Sulik A, Kemona A, Sulik M, Ołdak E. [Mast cells in chronic gastritis of children]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2001;10:156-160. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Nakajima S, Krishnan B, Ota H, Segura AM, Hattori T, Graham DY, Genta RM. Mast cell involvement in gastritis with or without Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:746-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Plebani M, Basso D, Rugge M, Vianello F, Di Mario F. Influence of Helicobacter pylori on tryptase and cathepsin D in peptic ulcer. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:2473-2476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Terada T, Matsunaga Y. Increased mast cells in hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2000;33:961-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Balázs M, Illyés G, Vadász G. Mast cells in ulcerative colitis. Quantitative and ultrastructural studies. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1989;57:353-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | King T, Biddle W, Bhatia P, Moore J, Miner PB. Colonic mucosal mast cell distribution at line of demarcation of active ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:490-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Raithel M, Matek M, Baenkler HW, Jorde W, Hahn EG. Mucosal histamine content and histamine secretion in Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and allergic enteropathy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1995;108:127-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dvorak AM, Monahan RA, Osage JE, Dickersin GR. Crohn's disease: transmission electron microscopic studies. II. Immunologic inflammatory response. Alterations of mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, and the microvasculature. Hum Pathol. 1980;11:606-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lloyd G, Green FH, Fox H, Mani V, Turnberg LA. Mast cells and immunoglobulin E in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1975;16:861-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nakamura A, Yamazaki K, Suzuki K, Sato S. Increased portal tract infiltration of mast cells and eosinophils in primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2245-2249. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Matsunaga Y, Kawasaki H, Terada T. Stromal mast cells and nerve fibers in various chronic liver diseases: relevance to hepatic fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1923-1932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Bardadin KA, Scheuer PJ. Mast cells in acute hepatitis. J Pathol. 1986;149:315-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zimnoch L, Szynaka B, Puchalski Z. Mast cells and pancreatic stellate cells in chronic pancreatitis with differently intensified fibrosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1135-1138. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Atkinson JB, Harlan CW, Harlan GC, Virmani R. The association of mast cells and atherosclerosis: a morphologic study of early atherosclerotic lesions in young people. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:154-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Laine P, Kaartinen M, Penttilä A, Panula P, Paavonen T, Kovanen PT. Association between myocardial infarction and the mast cells in the adventitia of the infarct-related coronary artery. Circulation. 1999;99:361-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kovanen PT, Kaartinen M, Paavonen T. Infiltrates of activated mast cells at the site of coronary atheromatous erosion or rupture in myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;92:1084-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hamada H, Terai M, Kimura H, Hirano K, Oana S, Niimi H. Increased expression of mast cell chymase in the lungs of patients with congenital heart disease associated with early pulmonary vascular disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1303-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Turlington BS, Edwards WD. Quantitation of mast cells in 100 normal and 92 diseased human hearts. Implications for interpretation of endomyocardial biopsy specimens. Am J Cardiovasc Pathol. 1988;2:151-157. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Patella V, de Crescenzo G, Lamparter-Schummert B, De Rosa G, Adt M, Marone G. Increased cardiac mast cell density and mediator release in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Inflamm Res. 1997;46 Suppl 1:S31-S32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Patella V, Marinò I, Arbustini E, Lamparter-Schummert B, Verga L, Adt M, Marone G. Stem cell factor in mast cells and increased mast cell density in idiopathic and ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1998;97:971-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Rüger BM, Hasan Q, Greenhill NS, Davis PF, Dunbar PR, Neale TJ. Mast cells and type VIII collagen in human diabetic nephropathy. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1215-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Toda S, Tokuda Y, Koike N, Yonemitsu N, Watanabe K, Koike K, Fujitani N, Hiromatsu Y, Sugihara H. Growth factor-expressing mast cells accumulate at the thyroid tissue-regenerative site of subacute thyroiditis. Thyroid. 2000;10:381-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | McKenna MJ. Histomorphometric study of mast cells in normal bone, osteoporosis and mastocytosis using a new stain. Calcif Tissue Int. 1994;55:257-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Tóth T, Tóth-Jakatics R, Jimi S, Ihara M, Urata H, Takebayashi S. Mast cells in rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1498-1505. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Kurusu A, Suzuki Y, Horikoshi S, Shirato I, Tomino Y. Relationship between mast cells in the tubulointerstitium and prognosis of patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephron. 2001;89:391-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Toms R, Weiner HL, Johnson D. Identification of IgE-positive cells and mast cells in frozen sections of multiple sclerosis brains. J Neuroimmunol. 1990;30:169-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Woolley DE, Tetlow LC. Mast cell activation and its relation to proinflammatory cytokine production in the rheumatoid lesion. Arthritis Res. 2000;2:65-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Dean G, Hoyland JA, Denton J, Donn RP, Freemont AJ. Mast cells in the synovium and synovial fluid in osteoarthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32:671-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Godfrey HP, Ilardi C, Engber W, Graziano FM. Quantitation of human synovial mast cells in rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:852-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF. Basophils and mast cells: morphologic insights into their biology, secretory patterns, and function. Prog Allergy. 1984;34:1-141. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Schulman ES, Kagey-Sobotka A, MacGlashan DW, Adkinson NF, Peters SP, Schleimer RP, Lichtenstein LM. Heterogeneity of human mast cells. J Immunol. 1983;131:1936-1941. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Benyon RC, Lowman MA, Church MK. Human skin mast cells: their dispersion, purification, and secretory characterization. J Immunol. 1987;138:861-867. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Church MK, Caulfield JP. Mast cell and basophil functions. Allergy. London: Gower Medical Publishing 1993; 5.1-5.12. |

| 54. | Schwartz LB. Tryptase from human mast cells: biochemistry, biology and clinical utility. Monogr Allergy. 1990;27:90-113. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Church MK, Benyon RC, Clegg LS, Holgate ST. Immunopharm-acology of mast cells. Hand-book of experimental pharmacology. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag 1989; 129-166. |

| 56. | Caulfield JP, Lewis RA, Hein A, Austen KF. Secretion in dissociated human pulmonary mast cells. Evidence for solubilization of granule contents before discharge. J Cell Biol. 1980;85:299-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Johnson RG, Carty SE, Fingerhood BJ, Scarpa A. The internal pH of mast cell granules. FEBS Lett. 1980;120:75-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Lagunoff D, Rickard A. Evidence for control of mast cell granule protease in situ by low pH. Exp Cell Res. 1983;144:353-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Irani AM, Schwartz LB. Neutral proteases as indicators of human mast cell heterogeneity. Monogr Allergy. 1990;27:146-162. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Goldstein SM, Kaempfer CE, Kealey JT, Wintroub BU. Human mast cell carboxypeptidase. Purification and characterization. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1630-1636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Irani AA, Schechter NM, Craig SS, DeBlois G, Schwartz LB. Two types of human mast cells that have distinct neutral protease compositions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4464-4468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 654] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Irani AM, Goldstein SM, Wintroub BU, Bradford T, Schwartz LB. Human mast cell carboxypeptidase. Selective localization to MCTC cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:247-253. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Meier HL, Heck LW, Schulman ES, MacGlashan DW. Purified human mast cells and basophils release human elastase and cathepsin G by an IgE-mediated mechanism. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1985;77:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Schechter NM, Irani AM, Sprows JL, Abernethy J, Wintroub B, Schwartz LB. Identification of a cathepsin G-like proteinase in the MCTC type of human mast cell. J Immunol. 1990;145:2652-2661. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Robinson C, Benyon C, Holgate ST, Church MK. The IgE- and calcium-dependent release of eicosanoids and histamine from human purified cutaneous mast cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93:397-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Bradding P, Walls AF, Church MK. Role of mast cells and baso-phils in inflammatory responses. Immunopharmacology of the respiratory system. Harcourt Brace Company, Publishers: Academic press 1995; 53-84. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 67. | Holgate ST. The role of mast cells and basophils in inflammation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30 Suppl 1:28-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Peters SP. Methanism of mast cell activation. Asthma and Rhinitis. Oxford: Blackwell 1995; 221-230. |

| 69. | Nagai S, Kitani S, Hirai K, Takaishi T, Nakajima K, Kihara H, Nonomura Y, Ito K, Morita Y. Pharmacological study of stem-cell-factor-induced mast cell histamine release with kinase inhibitors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;208:576-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Patella V, de Crescenzo G, Marinò I, Genovese A, Adt M, Gleich GJ, Marone G. Eosinophil granule proteins activate human heart mast cells. J Immunol. 1996;157:1219-1225. [PubMed] |

| 71. | He S, Gaça MD, Walls AF. A role for tryptase in the activation of human mast cells: modulation of histamine release by tryptase and inhibitors of tryptase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:289-297. [PubMed] |

| 72. | Nolte H, Spjeldnaes N, Kruse A, Windelborg B. Histamine release from gut mast cells from patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 1990;31:791-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 73. | Nishida Y, Murase K, Isomoto H, Furusu H, Mizuta Y, Riddell RH, Kohno S. Different distribution of mast cells and macrophages in colonic mucosa of patients with collagenous colitis and inflammatory bowel disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:678-682. [PubMed] |

| 74. | He S, Peng Q, Walls AF. Potent induction of a neutrophil and eosinophil-rich infiltrate in vivo by human mast cell tryptase: selective enhancement of eosinophil recruitment by histamine. J Immunol. 1997;159:6216-6225. [PubMed] |

| 75. | He S, Walls AF. Human mast cell chymase induces the accumulation of neutrophils, eosinophils and other inflammatory cells in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:1491-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Gelbmann CM, Mestermann S, Gross V, Köllinger M, Schölmerich J, Falk W. Strictures in Crohn's disease are characterised by an accumulation of mast cells colocalised with laminin but not with fibronectin or vitronectin. Gut. 1999;45:210-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Sasaki Y, Tanaka M, Kudo H. Differentiation between ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease by a quantitative immunohistochemical evaluation of T lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes and mast cells. Pathol Int. 2002;52:277-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Lilja I, Gustafson-Svärd C, Franzén L, Sjödahl R. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in ileal mast cells in patients with Crohn's disease. Digestion. 2000;61:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Middel P, Reich K, Polzien F, Blaschke V, Hemmerlein B, Herms J, Korabiowska M, Radzun HJ. Interleukin 16 expression and phenotype of interleukin 16 producing cells in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2001;49:795-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Lynch EA, Heijens CA, Horst NF, Center DM, Cruikshank WW. Cutting edge: IL-16/CD4 preferentially induces Th1 cell migration: requirement of CCR5. J Immunol. 2003;171:4965-4968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Schreiber S. Monocytes or T cells in Crohn's disease: does IL-16 allow both to play at that game. Gut. 2001;49:747-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Stoyanova II, Gulubova MV. Mast cells and inflammatory mediators in chronic ulcerative colitis. Acta Histochem. 2002;104:185-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Tsuneyama K, Saito K, Ruebner BH, Konishi I, Nakanuma Y, Gershwin ME. Immunological similarities between primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic sclerosing sialadenitis: report of the overlapping of these two autoimmune diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:366-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Halme L, Kärkkäinen P, Rautelin H, Kosunen TU, Sipponen P. High frequency of helicobacter negative gastritis in patients with Crohn's disease. Gut. 1996;38:379-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Locher C, Tipold A, Welle M, Busato A, Zurbriggen A, Griot-Wenk ME. Quantitative assessment of mast cells and expression of IgE protein and mRNA for IgE and interleukin 4 in the gastrointestinal tract of healthy dogs and dogs with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Vet Res. 2001;62:211-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Araki Y, Andoh A, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. Development of dextran sulphate sodium-induced experimental colitis is suppressed in genetically mast cell-deficient Ws/Ws rats. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;119:264-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Santos J, Yang PC, Söderholm JD, Benjamin M, Perdue MH. Role of mast cells in chronic stress induced colonic epithelial barrier dysfunction in the rat. Gut. 2001;48:630-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Dvorak AM, McLeod RS, Onderdonk A, Monahan-Earley RA, Cullen JB, Antonioli DA, Morgan E, Blair JE, Estrella P, Cisneros RL. Ultrastructural evidence for piecemeal and anaphylactic degranulation of human gut mucosal mast cells in vivo. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1992;99:74-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Bischoff SC, Wedemeyer J, Herrmann A, Meier PN, Trautwein C, Cetin Y, Maschek H, Stolte M, Gebel M, Manns MP. Quantitative assessment of intestinal eosinophils and mast cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Histopathology. 1996;28:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Crivellato E, Finato N, Isola M, Ribatti D, Beltrami CA. Low mast cell density in the human duodenal mucosa from chronic inflammatory duodenal bowel disorders is associated with defective villous architecture. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:601-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Knutson L, Ahrenstedt O, Odlind B, Hällgren R. The jejunal secretion of histamine is increased in active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:849-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Schwab D, Hahn EG, Raithel M. Enhanced histamine metabolism: a comparative analysis of collagenous colitis and food allergy with respect to the role of diet and NSAID use. Inflamm Res. 2003;52:142-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Winterkamp S, Weidenhiller M, Otte P, Stolper J, Schwab D, Hahn EG, Raithel M. Urinary excretion of N-methylhistamine as a marker of disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3071-3077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Weidenhiller M, Raithel M, Winterkamp S, Otte P, Stolper J, Hahn EG. Methylhistamine in Crohn's disease (CD): increased production and elevated urine excretion correlates with disease activity. Inflamm Res. 2000;49 Suppl 1:S35-S36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Fox CC, Lichtenstein LM, Roche JK. Intestinal mast cell responses in idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Histamine release from human intestinal mast cells in response to gut epithelial proteins. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1105-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Raithel M, Schneider HT, Hahn EG. Effect of substance P on histamine secretion from gut mucosa in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:496-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Fargeas MJ, Theodorou V, More J, Wal JM, Fioramonti J, Bueno L. Boosted systemic immune and local responsiveness after intestinal inflammation in orally sensitized guinea pigs. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:53-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Repka-Ramirez MS. New concepts of histamine receptors and actions. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2003;3:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Bertaccini G, Coruzzi G. An update on histamine H3 receptors and gastrointestinal functions. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:2052-2063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Rangachari PK. Histamine: mercurial messenger in the gut. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:G1-13. [PubMed] |

| 101. | Homaidan FR, Tripodi J, Zhao L, Burakoff R. Regulation of ion transport by histamine in mouse cecum. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;331:199-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Traynor TR, Brown DR, O'Grady SM. Effects of inflammatory mediators on electrolyte transport across the porcine distal colon epithelium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;264:61-66. [PubMed] |

| 103. | Crowe SE, Luthra GK, Perdue MH. Mast cell mediated ion transport in intestine from patients with and without inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1997;41:785-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Moriarty D, Goldhill J, Selve N, O'Donoghue DP, Baird AW. Human colonic anti-secretory activity of the potent NK(1) antagonist, SR140333: assessment of potential anti-diarrhoeal activity in food allergy and inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:1346-1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Abraham WM. Tryptase: potential role in airway inflammation and remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L193-L196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | McEuen AR, He S, Brander ML, Walls AF. Guinea pig lung tryptase. Localisation to mast cells and characterisation of the partially purified enzyme. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:331-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | He S, Walls AF. Human mast cell tryptase: a stimulus of microvascular leakage and mast cell activation. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;328:89-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Cairns JA, Walls AF. Mast cell tryptase is a mitogen for epithelial cells. Stimulation of IL-8 production and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression. J Immunol. 1996;156:275-283. [PubMed] |

| 109. | Raithel M, Winterkamp S, Pacurar A, Ulrich P, Hochberger J, Hahn EG. Release of mast cell tryptase from human colorectal mucosa in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:174-179. |

| 110. | Kunzelmann K, Schreiber R, König J, Mall M. Ion transport induced by proteinase-activated receptors (PAR2) in colon and airways. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2002;36:209-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Molino M, Barnathan ES, Numerof R, Clark J, Dreyer M, Cumashi A, Hoxie JA, Schechter N, Woolkalis M, Brass LF. Interactions of mast cell tryptase with thrombin receptors and PAR-2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4043-4049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Cenac N, Coelho AM, Nguyen C, Compton S, Andrade-Gordon P, MacNaughton WK, Wallace JL, Hollenberg MD, Bunnett NW, Garcia-Villar R. Induction of intestinal inflammation in mouse by activation of proteinase-activated receptor-2. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1903-1915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Mall M, Gonska T, Thomas J, Hirtz S, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. Activation of ion secretion via proteinase-activated receptor-2 in human colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G200-G210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Kim JA, Choi SC, Yun KJ, Kim DK, Han MK, Seo GS, Yeom JJ, Kim TH, Nah YH, Lee YM. Expression of protease-activated receptor 2 in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:224-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Krishnaswamy G, Kelley J, Johnson D, Youngberg G, Stone W, Huang SK, Bieber J, Chi DS. The human mast cell: functions in physiology and disease. Front Biosci. 2001;6:D1109-D1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | He S, Walls AF. The induction of a prolonged increase in microvascular permeability by human mast cell chymase. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;352:91-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Scudamore CL, Jepson MA, Hirst BH, Miller HR. The rat mucosal mast cell chymase, RMCP-II, alters epithelial cell monolayer permeability in association with altered distribution of the tight junction proteins ZO-1 and occludin. Eur J Cell Biol. 1998;75:321-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Chen ZQ, He SH. Cloning and expression of human colon mast cell carboxypeptidase. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:342-347. [PubMed] |

| 119. | Gaffney PR, Doyle CT, Gaffney A, Hogan J, Hayes DP, Annis P. Paradoxical response to heparin in 10 patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:220-223. [PubMed] |

| 120. | Evans RC, Wong VS, Morris AI, Rhodes JM. Treatment of corticosteroid-resistant ulcerative colitis with heparin--a report of 16 cases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:1037-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Yoshikane H, Sakakibara A, Ayakawa T, Taki N, Kawashima H, Arakawa D, Hidano H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in an ulcerative colitis case not associated with surgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1608-1610. [PubMed] |

| 122. | Ang YS, Mahmud N, White B, Byrne M, Kelly A, Lawler M, McDonald GS, Smith OP, Keeling PW. Randomized comparison of unfractionated heparin with corticosteroids in severe active inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1015-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Folwaczny C, Wiebecke B, Loeschke K. Unfractioned heparin in the therapy of patients with highly active inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1551-1555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | Dotan I, Hallak A, Arber N, Santo M, Alexandrowitz A, Knaani Y, Hershkoviz R, Brazowski E, Halpern Z. Low-dose low-molecular weight heparin (enoxaparin) is effective as adjuvant treatment in active ulcerative colitis: an open trial. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2239-2244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 125. | Vrij AA, Jansen JM, Schoon EJ, de Bruine A, Hemker HC, Stockbrugger RW. Low molecular weight heparin treatment in steroid refractory ulcerative colitis: clinical outcome and influence on mucosal capillary thrombi. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2001;234:41-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 126. | Törkvist L, Thorlacius H, Sjöqvist U, Bohman L, Lapidus A, Flood L, Agren B, Raud J, Löfberg R. Low molecular weight heparin as adjuvant therapy in active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1323-1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 127. | Papa A, Danese S, Gasbarrini A, Gasbarrini G. Review article: potential therapeutic applications and mechanisms of action of heparin in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1403-1409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 128. | Michell NP, Lalor P, Langman MJ. Heparin therapy for ulcerative colitis Effects and mechanisms. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:449-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 129. | Day R, Forbes A. Heparin, cell adhesion, and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet. 1999;354:62-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 130. | McCarty MF. Vascular heparan sulfates may limit the ability of leukocytes to penetrate the endothelial barrier--implications for use of glucosamine in inflammatory disorders. Med Hypotheses. 1998;51:11-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 131. | Wan MX, Liu Q, Wang Y, Thorlacius H. Protective effect of low molecular weight heparin on experimental colitis: role of neutrophil recruitment and TNF-alpha production. Inflamm Res. 2002;51:182-187. |

| 132. | Salas A, Sans M, Soriano A, Reverter JC, Anderson DC, Piqué JM, Panés J. Heparin attenuates TNF-alpha induced inflammatory response through a CD11b dependent mechanism. Gut. 2000;47:88-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 133. | Dobosz M, Mionskowska L, Dobrowolski S, Dymecki D, Makarewicz W, Hrabowska M, Wajda Z. Is nitric oxide and heparin treatment justified in inflammatory bowel disease An experimental study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1996;56:657-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 134. | Fries W, Pagiaro E, Canova E, Carraro P, Gasparini G, Pomerri F, Martin A, Carlotto C, Mazzon E, Sturniolo GC. The effect of heparin on trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced colitis in the rat. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:229-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 135. | Fox CC, Lazenby AJ, Moore WC, Yardley JH, Bayless TM, Lichtenstein LM. Enhancement of human intestinal mast cell mediator release in active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:119-124. [PubMed] |

| 136. | Ajuebor MN, Singh A, Wallace JL. Cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandin D(2) is an early anti-inflammatory signal in experimental colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G238-G244. [PubMed] |

| 137. | Casellas F, Guarner F, Antolín M, Rodríguez R, Salas A, Malagelada JR. Abnormal leukotriene C4 released by unaffected jejunal mucosa in patients with inactive Crohn's disease. Gut. 1994;35:517-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 138. | Eliakim R, Karmeli F, Razin E, Rachmilewitz D. Role of platelet-activating factor in ulcerative colitis. Enhanced production during active disease and inhibition by sulfasalazine and prednisolone. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1167-1172. [PubMed] |

| 139. | Rachmilewitz D, Karmeli F, Eliakim R. Platelet-activating factor--a possible mediator in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1990;172:19-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 140. | Denizot Y, Chaussade S, Nathan N, Colombel JF, Bossant MJ, Cherouki N, Benveniste J, Couturier D. PAF-acether and acetylhydrolase in stool of patients with Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:432-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 141. | Sobhani I, Hochlaf S, Denizot Y, Vissuzaine C, Rene E, Benveniste J, Lewin MM, Mignon M. Raised concentrations of platelet activating factor in colonic mucosa of Crohn's disease patients. Gut. 1992;33:1220-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 142. | Thornton M, Solomon MJ. Crohn's disease: in defense of a microvascular aetiology. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:287-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 143. | Riehl TE, Stenson WF. Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolases in Caco-2 cells and epithelium of normal and ulcerative colitis patients. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1826-1834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 144. | Ferraris L, Karmeli F, Eliakim R, Klein J, Fiocchi C, Rachmilewitz D. Intestinal epithelial cells contribute to the enhanced generation of platelet activating factor in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1993;34:665-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |