Published online Nov 15, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3274

Revised: April 4, 2004

Accepted: April 29, 2004

Published online: November 15, 2004

AIM: Studies on Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) and gastrodu- odenal diseases have focused mainly on the distal sites of the stomach, but relationship with the gastric cardia is lacking. The aim of this study is to determine if the gastric topology and genotypic distribution of H pylori were associated with different upper gastrointestinal pathologies in a multi-ethnic Asian population.

METHODS: Gastric biopsies from the cardia, body/corpus and antrum were endoscoped from a total of 155 patients with dyspepsia and/or reflux symptoms, with informed consent. H pylori isolates obtained were tested for the presence of 26kDa, ureC, cagA, vacA, iceA1, iceA2 and babA2 genes using PCR while DNA fingerprints were generated using random amplification polymorphic DNA (RAPD).

RESULTS: H pylori was present in 51/155 (33%) of patients studied. Of these, 16, 15 and 20 were isolated from patients with peptic ulcer diseases, gastroesophageal reflux diseases and non-ulcer dyspepsia, respectively. Of the H pylori positive patients, 75% (38/51) had H pylori in all three gastric sites. The prevalence of various genes in the H pylori isolates was shown to be similar irrespective of their colonization sites as well as among the same site of different patients. The RAPD profiles of H pylori isolates from different gastric sites were highly similar among intra-patients but varied greatly between different patients.

CONCLUSION: Topographic colonization of H pylori and the virulence genes harboured by these isolates have no direct bearing to the clinical state of the patients. In multi-ethnic Singapore, the stomach of each patient is colonized by a predominant strain of H pylori, irrespective of the clinical diagnosis.

-

Citation: Ho YW, Ho KY, Ascencio F, Ho B. Neither gastric topological distribution nor principle virulence genes of

Helicobacter pylori contributes to clinical outcomes. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(22): 3274-3277 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i22/3274.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3274

Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) is a common gastric pathogen that has infected more than 50% of the world’s population[1]. It is the major aetiological agent of chronic active gastritis and is generally accepted as being the primary cause of peptic ulcer disease and a carcinogenic factor for gastric cancer (GC)[2]. However, only a minority of H pylori infected subjects develops these diseases. This has led to the suggestion that clinical sequelae that develop may be dependent upon differentially expressed bacterial determinants, e.g., bacterial virulence genes: cagA, vacA, iceA1, iceA2, babA2[3-5]. In many parts of Asia, the prevalence of cagA and vacA strains is high regardless of the presence or absence of disease states[6]. This limits the usefulness of using these genes as markers to predict clinical outcome. Instead, other factors like host susceptibility as well as specific interactions between a particular strain and its host that occur during decades of coexistence might have contributed to an increased risk of developing certain clinical manifestations[7].

Our current knowledge on the epidemiology of the organism is predominantly based on data obtained from serologic studies. It has also been reported that a single strain of H pylori predominates the gastric antrum and corpus of infected patients in Singapore[8]. However, there is a need to study whether the topographic distribution of H pylori genotypes in various gastric sites in patients of different ethnic origins affects the disease state. Being an Asian country with a multi-ethnic population, Singapore is suitable for this investigation.

Consecutive patients with dyspepsia and/or reflux symptoms presenting for upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination to one of the authors (KYH) and who have not been exposed to antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors (PPI) or bismuth compounds within the past four week were invited to participate in the study. Patients who previously had been treated for H pylori infection, patients who refused gastric biopsies, patients who were unable to give consent because of age or mental illness and patients in whom gastric and oesophageal biopsies were contraindicated (e.g., coagulopathy, oesophageal varices and severe co-morbidity), subjects who were pregnant and those who were < 18 years old, were excluded. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

A total of 155 patients were included in the study. The patient population comprised 122 (79%) Chinese, 17 (11%) Indians, 8 (5%) Malays and 8 (5%) subjects of other ethnicities. Of these, 95 (61%) were males and 60 (39%) females. The mean age was 48.4 ± 15.5 (range, 24-88) years. Based on clinical history and endoscopic examination, patients were classified into the following groups: gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (n = 50), peptic ulcer disease (PUD) (n = 36) and non-ulcer dyspepsia (NUD) (n = 69). GERD was defined as the presence of predominant symptoms of reflux, e.g., heartburn, acid regurgitation and/or the presence of any length of mucosal break in the oesophagus due to gastroesophageal reflux. NUD was defined as patients with neither a history of GERD nor endoscopic evidence of organic pathologies. PUD refers to patients who were either diagnosed upon endoscopy as suffering from gastric ulcers (ulcers at the corpus) or duodenal ulcers (ulcers at the antrum). A total of 465 biopsy specimens were obtained from the 155 patients.

After an overnight or six hour fast, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed according to standard technique. From each patient, one biopsy specimens was obtained using sterilized standard biopsy forceps from each of the three sites of the stomach: the cardia just below the z-line, the middle gastric corpus and the antrum within 2 cm of the pylorus, in that order. The biopsy forceps were thoroughly cleaned with alcohol swaps between biopsies to avoid contamination between specimens. The biopsies were transported in 0.85% sterile saline to the microbiological laboratory for processing within 6 h.

Each biopsy specimen was homogenised aseptically in 500 μL of Brain Heart Infusion Broth (BHI, Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, UK) enriched with 4 g/L yeast extract (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, UK). Approximately 100 μL homogenised specimens in BHI broth were inoculated onto H pylori selective chocolate blood agar plates and non-selective chocolate blood agar plates respectively. The selective blood chocolate agar was supplemented with 3 mg/mL vancomycin, 5 mg/mL trimethoprim, 10 mg/mL nalidixic acid and 2 mg/mL amphotericin B. All the antibiotics were from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie, Steinheim, Germany. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for up to 14 d in an incubator (Forma Scientific, USA) containing 50 mL/L CO2.

Aliquots of 50 μL of BHI-biospy suspension were each inoculated into catalase reagent, oxidase reagent and 20 g/L urea solution for their respective testing. An isolate was identified as H pylori if minute (-1 mm in diameter) rounded translucent colonies with gram-negative S-shaped motile cells that exhibited positive catalase, oxidase and urease activities. For this study, a patient was considered positive for H pylori if the organism was isolated from any of the three gastric sites.

Genotyping of H pylori

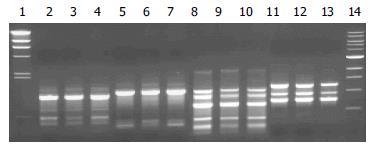

The DNA of each 3-d old H pylori culture was extracted according to the method as described by Hua et al[8]. A 50 ng working stock of DNA was used to amplify 26kDa[9], ureC[10], cagA[11], vacA[12], iceA1[5], iceA2[5] and babA2[4] genes according to the protocol as described by Zheng et al[6] using the specific forward and reverse primers for each of the corresponding genes (Table 1). The DNA fingerprint of the H pylori was obtained by PCR using the universal primer, 5’- AACGCGCAAC-3’ and amplified according to protocol as described by Hua et al[13]. The PCR products obtained were electrophoresed and the ethidium bromide stained gels[13] were then photographed with filtered UV illumination on Chemi Genius2 (SynGene, Cambridge, UK).

| Region | Primer | Nucleotide sequence (5'→3') | PCR product (bp) | Reference |

| 26kDa | 26kDa-F | TGGCGTGTCTATTGACAGCGAGC | 298 | 9 |

| 26kDa-R | CCTGCTGGGCATACTTCACCAAG | |||

| ureC | ureC-F | AAGCTTTTAGGGGTGTTAGGGGTTT | 294 | 10 |

| ureC-R | AAGCTTACTTTCTAACACTAACGC | |||

| cagA | cagA-F | AATACACCAACGCCTCCAAG | 400 | 11 |

| cagA-R | TTGTTGCCGCTTTTGCTCTC | |||

| vacA | vacA-F | GCTTCTCTTACCACCAATGC | 1160 | 12 |

| vacA-R | TGTCAGGGTTGTTCACCATG | |||

| m2-R | CATAACTAGCGCCTTGCAC | |||

| iceA1 | iceA1-F | GTGTTTTTAACCAAAGTATC | 246 | 5 |

| iceA1-R | CTATAGCCAGTCTCTTTGCA | 5 | ||

| iceA2 | iceA2-F | GTTGGGTDTDTCACAATTTAT | 229/334 | 5 |

| iceA2-R | TTGCCCTATTTTCTAGTAGGT | 5 | ||

| babA2 | babA2-F | AATCCAAAAAGGAGAAAAAGTATGAAA | 831 | 4 |

| babA2-R | TGTTAGTGATTTCGGTGTAGGACA | 4 |

The significance of the results obtained was calculated using SPSS v.10 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago IL) to determine the Pearson chi-square whereby a P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Of the 155 patients studied, 51 (33%) were found to harbour H pylori in at least one of the 3 gastric biopsy sites. In all, 43, 47 and 44 isolates were obtained from gastric antrum, corpus and cardia respectively, giving a total of 134 isolates. H pylori was present in 16/36 (44%) PUD patients as compared with 15/50 (30%) GERD patients (P = 0.169) and 20/69 (29%) NUD patients (P = 0.113) (Table 2).

| Groups | No. of patients | No. of biopsies | No. of H pylori (+) | P |

| PUD | 36 | 108 | 16 (44%) | - |

| GERD | 50 | 150 | 15 (30%) | 0.169 |

| NUD | 69 | 207 | 20 (29%) | 0.113 |

Of the 51 H pylori positive patients, 38 (75%) showed the presence of H pylori in all the three gastric sites while 1 (1%), 2 (4%) and 4 (8%) had H pylori isolated from antrum & corpus, antrum & cardia, and corpus & cardia, respectively. H pylori was isolated from a single site of the stomach in 6 (12%) patients, among which 2 isolates were from the antrum and 4 were from the corpus. This topographical pattern of H pylori colonization was observed in all the patients irrespective of the underlying clinical diagnosis.

All the H pylori isolates possessed the 26kDa gene and the ureC genes. The prevalence of virulence genes of interest were present in equal ratios in all the H pylori isolates obtained from all the 3 different gastric biopsy sites: 74%-81% for cagA and 80%-86% for vacA; 53%-59% for iceA1 and 36%-42% for babA2 regardless of the underlying clinical diagnosis. However, the iceA2 gene was present less frequently, at 20%-26% of the H pylori isolates. It is noted that the difference in gene frequency between the various sites was also not statistically significant (Table 3).

| Antrum (%) n = 43 | Body/Corpus (%) n = 47 | Cardia(%) n = 44 | |

| Clinical Diagnosis | |||

| PUD | 12 (33) | 15 (42) | 12 (33) |

| GERD | 13 (26) | 15 (30) | 14 (28) |

| NUD | 18 (25) | 17 (24) | 18 (26) |

| Genotype | |||

| 26kDa | 43 (100) | 47 (100) | 44 (100) |

| ureC | 43 (100) | 47 (100) | 44 (100) |

| cagA | 35 (81) | 35 (74) | 33 (75) |

| vacA | 37 (86) | 38 (81) | 35 (80) |

| iceA1 | 25 (58) | 25 (53) | 26 (59) |

| iceA2 | 10 (23) | 12 (26) | 9 (20) |

| babA2 | 18 (42) | 20 (38) | 16 (36) |

Similar observation was noted with respect to the distribution of virulence genes of H pylori isolated from the same site among the different disease groups. The prevalence for each virulence gene within the same site was highly similar. No significant association of the virulence gene was found to be associated with a particular biopsied site, regardless of the disease state, with the exception of cagA in isolates from the corpus of the stomach of GERD patients (Table 4).

| Isolates | 26kDa (%) | ureC (%) | cagA (%) | vacA (%) | iceA1(%) | iceA2(%) | babA2(%) | |

| Antrum | ||||||||

| PUD | 12 | 12 (100) | 12 (100) | 9 (75) | 10 (83) | 6 (50) | 4 (33) | 6 (50) |

| GERD | 13 | 13 (100) | 13 (100) | 11 (85) | 11 (85) | 7 (54) | 2 (15) | 6 (46) |

| NUD | 18 | 18 (100) | 18 (100) | 15 (83) | 16 (89) | 12 (67) | 4 (22) | 6 (33) |

| Body/Corpus | ||||||||

| PUD | 15 | 15 (100) | 15 (100) | 9 (60) | 10 (67) | 6 (40) | 5 (33) | 7 (47) |

| GERD | 15 | 15 (100) | 15 (100) | 14 (93)1 | 14 (93) | 8 (53) | 3 (20) | 8 (53) |

| NUD | 17 | 17 (100) | 17 (100) | 12 (71) | 14 (82) | 11 (65) | 4 (24) | 5 (29) |

| Cardia | ||||||||

| PUD | 12 | 12 (100) | 12 (100) | 9 (75) | 11 (92) | 5 (42) | 2 (17) | 3 (25) |

| GERD | 14 | 14 (100) | 14 (100) | 12 (86) | 11 (79) | 8 (57) | 2 (14) | 7 (50) |

| NUD | 18 | 18 (100) | 18 (100) | 12 (67) | 13 (72) | 13 (72) | 5 (28) | 7 (39) |

For comparison, differences in 2 or more bands of the RAPD profile are considered different while variations in band intensity were not taken into account. On this basis, the RAPD profiles of all the H pylori strains isolated showed an overall similarity in profiles within individual patients, with minor differences such as the presence or absence of a single band. However, distinct differences in the DNA profiles were observed between patients (Figure 1). In this study, no comparison could be made in 6 patients since H pylori was isolated from only one site of the stomach in these patients.

It is noted that 50% of the world’s population are infected with H pylori but only a small proportion manifest different gastroduodenal diseases[14]. One of the factors contributing to this phenomenon could be the patchy distribution of H pylori in different gastric sites of the stomach As most of the earlier studies focused on H pylori isolated from the distal sites of the stomach[8,15], the present study shows that H pylori isolates obtained from all the 3 gastric sites, namely cardia, corpus and antrum, in 38/51 (75%) H pylori patients were similar genotypically. Care was taken in cleaning and disinfecting the biopsy forceps between biopsies to avoid contamination between specimens. The results imply that H pylori colonises the entire stomach instead of a predominant site in three quarters of our H pylori positive patients, irrespective of the underlying clinical diagnosis. The finding suggests that the site of H pylori colonization or topographic distribution does not contribute significantly to the outcome of the infection.

While studies in Europe suggested that virulence genes, e.g., vacA and vacA affect the clinical outcome of H pylori infection[3,5], the present study confirms previous studies carried out in Asian countries[6,15] that showed a high prevalence of vacA and vacA genes regardless of the clinical outcome. This study comprised Singapore patients of various ethnicities (Chinese, Malays, Indians and other races), also shows that each of the virulence genes, i.e., cagA, vacA, iceA1, iceA2 and babA2 were equally distributed in H pylori isolates obtained from all the three anatomical sites studied regardless of the disease states. Similarly, comparisons of these genes from the same anatomical site of different patients showed no significant presence, except for vacA in the corpus of GERD isolates. However, it is important to point out that the number of isolates obtained from each is relatively low (n ≤ 18), regardless of the disease state. As such, the significant presence of vacA in the corpus of GERD patients needs further analysis with a larger pool of samples to confirm conclusively its contribution to the onset of GERD. The data therefore suggest that virulence genes and their topographic distribution do not contribute to the clinical status, at least in the Singapore population. This study supports the earlier reports[15-17] that identifying such virulence genes in order to predict clinical outcome may be of limited value in Asian H pylori isolates.

The finding that RAPD profiles of the H pylori isolates were similar from 3 different anatomical sites (antrum, corpus & cardia) of each patient further strengthens our earlier study[9] where isolates from 2 sites (antrum & corpus) were identical. This finding is complemented by the similar status of presence of various virulence genes in these isolates obtained from the respective patients. As such, the isolation of a strain from any gastric site in a single patient could be taken as representative of H pylori infection present in the H pylori infected gastric environment.

This study, which included consecutive patients with dyspepsia and/or reflux symptoms showed a lower frequency of PUD as compared with that of GERD. H pylori was found in only 44% of patients with PUD. This seems to run counter to the generally held view that H pylori occurs frequently in Asians patients with PUD[13]. However, this finding is supported by an earlier study from the same unit[18] showing the frequency of reflux oesophagitis was increasing while that of duodenal ulceration was decreasing in Singapore. The high frequency of patients with GERD in this study also relates to the fact that the endoscopist (KYH) sees most of the GERD patients in the hospital. The decreasing frequency of H pylori associated peptic ulcers was reported to be attributed to the increasing proportion of ulcers due to NSAID use[19].

In summary, the present study shows that in Singapore, the topographic colonization of H pylori and their virulence genes within the host stomach do not play a significant role in the clinical manifestations of H pylori infection. This study also demonstrates that in Singapore, which has a multiethnic Asian population, the stomach of each patient with dyspeptic and/or reflux symptoms is colonized by a single predominant strain of H pylori, irrespective of the site of isolation and the clinical diagnosis of the patient. We suggest that the pathogenesis of H pylori induced gastroduodenal diseases is due to a more complex mechanism possibly involving host-pathogen interaction, environmental and dietary factors.

Edited by Pan BR and Zhang JZ Proofread by Xu FM

| 1. | Everhart JE. Recent developments in the epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000;29:559-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Go MF. Review article: natural history and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16 Suppl 1:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Arents NL, van Zwet AA, Thijs JC, Kooistra-Smid AM, van Slochteren KR, Degener JE, Kleibeuker JH, van Doorn LJ. The importance of vacA, cagA, and iceA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori infection in peptic ulcer disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2603-2608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gerhard M, Lehn N, Neumayer N, Borén T, Rad R, Schepp W, Miehlke S, Classen M, Prinz C. Clinical relevance of the Helicobacter pylori gene for blood-group antigen-binding adhesin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12778-12783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Doorn LJ, Figueiredo C, Sanna R, Plaisier A, Schneeberger P, de Boer W, Quint W. Clinical relevance of the cagA, vacA, and iceA status of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:58-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zheng PY, Hua J, Yeoh KG, Ho B. Association of peptic ulcer with increased expression of Lewis antigens but not cagA, iceA, and vacA in Helicobacter pylori isolates in an Asian population. Gut. 2000;47:18-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Peek RM. The biological impact of Helicobacter pylori colonization. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2001;12:151-166. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Hua J, Ling KL, Ng HS, Ho B. Isolation of a single strain of Helicobacter pylori from the antrum and body of individual patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:1129-1134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hammar M, Tyszkiewicz T, Wadström T, O'Toole PW. Rapid detection of Helicobacter pylori in gastric biopsy material by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:54-58. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Labigne A, Cussac V, Courcoux P. Shuttle cloning and nucleotide sequences of Helicobacter pylori genes responsible for urease activity. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1920-1931. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lage AP, Godfroid E, Fauconnier A, Burette A, Butzler JP, Bollen A, Glupczynski Y. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection by PCR: comparison with other invasive techniques and detection of vacA gene in gastric biopsy specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2752-2756. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Xiang Z, Censini S, Bayeli PF, Telford JL, Figura N, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. Analysis of expression of CagA and VacA virulence factors in 43 strains of Helicobacter pylori reveals that clinical isolates can be divided into two major types and that CagA is not necessary for expression of the vacuolating cytotoxin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:94-98. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Hua J, Ho B. Is the coccoid form of Helicobacter pylori viable. Microbios. 1996;87:103-112. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Höcker M, Hohenberger P. Helicobacter pylori virulence factors--one part of a big picture. Lancet. 2003;362:1231-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Kim SY, Woo CW, Lee YM, Son BR, Kim JW, Chae HB, Youn SJ, Park SM. Genotyping CagA, VacA subtype, IceA1, and BabA of Helicobacter pylori isolates from Korean patients, and their association with gastroduodenal diseases. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:579-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim JM, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS, Kim CY. Virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori in Korean isolates do not influence proinflammatory cytokine gene expression and apoptosis in human gastric epithelial cells, nor do these factors influence the clinical outcome. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:898-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Park SM, Park J, Kim JG, Cho HD, Cho JH, Lee DH, Cha YJ. Infection with Helicobacter pylori expressing the vacA gene is not associated with an increased risk of developing peptic ulcer diseases in Korean patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:923-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ho KY, Gwee KA, Yeoh KG, Lim SG, Kang JY. Increasing frequency of reflux esophagitis in Asian patients. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:A1246. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Ong TZ, Ho KY. The increasing frequency of non-Helicobacter pylori peptic ulcer disease in an Asian country is related to NSAID use. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2003;57:AB153. |