Published online Nov 15, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3245

Revised: December 4, 2003

Accepted: December 16, 2003

Published online: November 15, 2004

AIM: Survivin is a novel antiapoptotic gene in which three splicing variants have been recently cloned and characterized. Survivin has been found to be abundantly expressed in a wide variety of human malignancies, whereas it is undetectable in normal adult tissues. We aimed to study the expression of three survivin splicing variants in gastric cancer, and to evaluate the prognostic significance of the expression of survivin variants in gastric cancer.

METHODS: Real time quantitative RT-PCR was performed to analyze the expression of survivin variants in 79 paired tumors and normal gastric mucosa samples at the mRNA level. Proliferative and apoptotic activity was measured using Ki-67 immunohistochemical analysis and the TUNEL method, respectively.

RESULTS: All the cases tested expressed wild-type survivin mRNA, which was not only the dominant transcript, but also a poor prognostic biomarker (P = 0.003). Non-antiapoptostic survivin-2B mRNA was correlated with tumor stage (P = 0.001), histological type (P = 0.004), and depth of tumor invasion (P = 0.041), while survivin-△Ex3 mRNA showed a significant association with apoptosis (P = 0.02).

CONCLUSION: Wild-type survivin mRNA expression levels are of important prognostic value and significant participation of survivin-2B and survivin-△Ex3 is suggested in gastric cancer development.

- Citation: Meng H, Lu CD, Sun YL, Dai DJ, Lee SW, Tanigawa N. Expression level of wild-type survivin in gastric cancer is an independent predictor of survival. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(22): 3245-3250

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i22/3245.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3245

Apoptosis, also called programmed cell death, plays an important role in the development and homeostasis of tissues. Deregulation of apoptosis is involved in carcinogenesis by abnormally prolonged cell survival, facilitating the accumulation of transforming mutations and promoting resistance to immunosurveillance[1]. Several studies have consistently shown that survivin could mediate suppression of apoptosis. Surprisingly, in a single copy of survivin gene, three alternatively splicing transcripts have been identified. In addition to wild-type survivin, two novel survivin variants (survivin-2B, survivin-△Ex3), which have different antiapoptotic properties, have been generated. Survivin-2B has lost its anti-apoptotic potential, whereas its anti-apoptotic potential is preserved in survivin-△Ex3[2,3]. Their different functions in carcinogenesis are largely unknown.

Gastric carcinoma is one of the most frequent human malignancies[4]. As shown by our group[5], 34.5% of gastric cancers expressed survivin protein and a positive correlation between accumulated p53 and survivin expression in neoplasia was found. In this study, we investigated the distribution of survivin variants in paired tumors and normal gastric mucosa samples at the mRNA level and assessed the potential relationship between the expression of survivin variants and proliferative activity, apoptosis or prognostic significance.

Matched pairs of tumors and normal gastric mucosa samples were obtained from 76 patients with gastric cancer and 1 patient with malignant lymphoma at the Department of General and Gastroenterological Surgery, Osaka Medical College Hospital during 2000-2002. The specimens resected at surgery were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until total RNA extraction. Clinicopathological parameters were assigned according to the principles outlined by Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma[6]. Samples included stage I cases (n = 22), stage II cases (n = 11), stages III cases (n = 20), stage IV cases (n = 26). There were 62 (78.5%) males and 17 (22.5%) females, and the mean age of the patients was 65.2 years (SD, 9.6 years; range, 40-87 years). No Patients received chemotherapy or radiation therapy either before or after surgery. The mean follow-up period was 19.7 mo (SD, 14.9 mo; range, 1.5-87 mo). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks of primary tumors were taken from pathological archives. Two to four μm thick serial sections of 2-4 thicken were prepared from the cut surface of the blocks at the maximum cross-section of the tumors.

Total RNA was extracted by an acid guanidinium-phenol-chloroform method using ISOGEN (Nippon Gene, Toyama, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Afterwards the total RNA was purified using DNase 1 (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Extracted total RNA pellets were dissolved with RNase free diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water.

Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized with 5 μg of total RNA and 20 pmoL oligo (dT)18 primer using an Advantage RNA-for-PCR kit (CLONTECH, Inc., Palo Alto, USA), with the exception of 200 U SurperScriptTM II RNase H- reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Inc., Carlsbad, USA) in a final 20 μL reaction volume. RT reactions were performed at 50 °C for 120 min. Finally, cDNA solution was diluted to a total volume 100 μL.

Quantitative real time RT-PCR was performed with a LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). As an internal control, housekeeping gene G6PDH mRNA expression was measured at the same time. DEPC-treated H2O was used as a negative control and MKN-74 was used as a positive control. Then, 1 μL of cDNA mixture was subjected to amplification in 10 μL reaction mixture. The PCR conditions were initial denaturation at 95 °Cfor 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 62 °C for 10 s for survivin, survivin-2B and survivin-△Ex3 (or at 63 °C for G6PDH), extension at 72 °C for 10 s, respectively. A standard curve using fluorescent data was generated from serial tenfold dilution of specific plasmids from 107 to 102 copies, respectively. The number of gene copies was calculated by the LightCycler Software Version3.5.3 according to the Fit Points Above Threshold method. Primer pairs and hybridization probes for survivin, survivin-2B, survivin-△Ex3 and G6PDH mRNA were as follows. The sequence of the common forward primer for survivin variants was 5’-CCACCGCATCTCTACATTCA-3’. To distinguish the 3 splice variants of survivin, the sequences of reverse primers for survivin variants were designed to correspond to exon/exon borders of the complementary strand (5’-TATGTTCCTCTATGGGGTCG-3’ for survivin, 5’-AGTGCTGGTATTACAGGCGT-3’ for survivin-2B, 5’-TTTCCTTTGCATGGGGTC -3’ for survivin-△Ex3). The sequences of common hybridization probes for survivin variants were 5’-CAAGTCTGGCTCGTTCT CAGTGGG-3’-FITC and LC Red640-5’-CAGTGGATGAAGCCAGCCTCG-3’. The sequence of the forward primer for G6PDH was 5’-TGGACCTGACCTACGGCAACAGATA-3’. The sequence of the reverse primer for G6PDH was 5’-GCCCTCATACTGGAAACCC-3’. The sequences of hybridization probes for G6PDH were 5’- TTTTCACCCCACTGCTGCACC-3’ -FITC and LC Red640 –5’-GATTGAGCTGGAGAAGCCCAAGC-3.

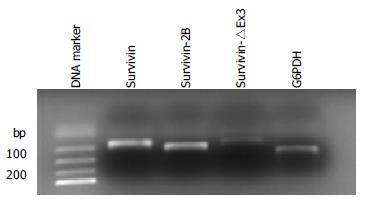

PCR products were additionally checked by electrophoresis on 30 g/L agarose gels (BIO-RAD, Inc., Hercules, USA) containing ethidium bromide and visualized under UV transillumination.

To confirm the identity of the PCR products, their bands were excised from agarose gels and isolated by a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan), ligated into a pGEM-T-cloning vector (Promega), and cloned according to standard protocols. Plasmid DNA was recovered using a Plasmid Mini kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan). Cycle was sequenced and analyzed in an ABI-PRISM310 (Applied Biosystems) using T7 or SP6-site specific primers. The sequences of the PCR products were compared with those in GenBank, which were found to be identical (Data not shown).

Immunohistochemical staining was performed by the standard avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex technique using L.V. Dako LSAB kit (DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark) as described previously[5,7,8]. The antibodies used were monoclonal mouse antibody Ki-67 (MIB-1, diluted 1:50; Immunotech, Marseilles, France). The labeling index (LI) of Ki-67 was determined in those tumor areas with positive stained nuclei. Five random areas within a section were chosen and counted under 200-fold magnification using a point counting technique. The average percentage of positivity was recorded as the Ki-67 LI for each case[7].

Apoptotic cells in tissue sections were detected by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL), using an Apop Tag in situ detection kit (Oncor, Gaithersburg, MD). The staining procedures were based on a method described previously[5,6,8]. The apoptotic index (AI) was expressed as the ratio of positively stained tumor cells and bodies to all tumor cells according to the criteria described elsewhere[5,7]. Five areas were randomly selected for counting under 400-fold magnification.

All statistical analyses were performed by the SPSS11.0 software package for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Differences in the numerical data between the two groups were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test. The χ2 test was further used to compare the distribution of individual variables and any correlation between AI or Ki-67 index and expression of survivin variants. The correlation between AI and expression of survivin variants for each case was also analyzed by Spearman’s rank correlation test. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and analyzed by the log rank test. A two-tailed P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Among the 79 tumor samples, survivin expression was detected in all tumor samples (79/79), survivin-2B expression was demonstrated in 78.5% (62/79) of the samples and survivin-△Ex3 expression was detected in 64.6% (51/79) of the samples (Figure 1). In contrast, survivin expression was detectable in 46 (58.2%) of the normal mucosa samples, while survivin2B expression and survivin-△Ex3 were detected in 23 (29.1%) and 12 (15.2%) of the mucosa samples respectively.

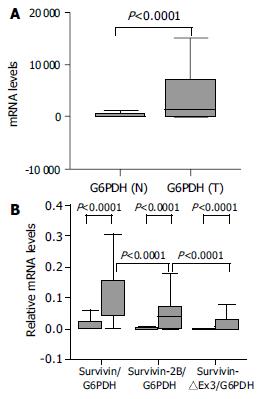

The relative amounts of survivin variant mRNA were determined by dividing the amount of survivin variant mRNA by that of G6PDH mRNA for each sample. In tumor samples, the relative levels of survivin-2B and survivin-△Ex3 was further normalized by matched survivin. Because three alternatively spliced variants are derived from a common hnRNA precursor pool, these ratios seemed to be independent of any possible bias imposed by variations in housekeeping gene expression levels[9,10]. Although there was a significant difference in G6PDH expression between normal tissues and cancer samples at the same amount of total RNA used (P < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test, Figure 2A), the survivin variant/G6PDH ratio in our cancer tissues were significantly higher than that in non-neoplastic tissues (P < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test, Figure 2B).

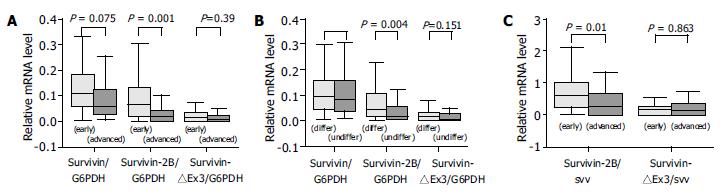

The expression level of survivin-2B was significantly (P = 0.001, Table 1, P < 0.0001, χ2 test, Figure 3A) decreased in advanced (III + IV) stage compared with early (I + II) tumor stage. Furthermore, the level of survivin-2B was inversely correlated with the grade of tumor differentiation (P = 0.004, Table 1, P = 0.023, χ2 test, Figure 3B) and depth of tumor invasion (P = 0.042, Table 1, P = 0.021, χ2 test). A stage-dependent decrease of survivin-2B was also confirmed by the ratio of survivin-2B/survivin (P = 0.018, Table 1, P = 0.022, χ2 test, Figure 3C).

| Parameters | No. of patients (%) | Sur/G6PDH | Sur-2B/G6PDH | Sur-△Ex3/G6PDH | Sur-2B/sur | Sur-△Ex3/sur |

| Gender (median) | ||||||

| Male | 62 (78.5) | P = 0.445 | P = 0.598 | P = 0.079 | P = 0.125 | P = 0.408 |

| Female | 17 (22.5) | |||||

| Age yr (median) | ||||||

| < 64 | 39 | P = 0.462 | P = 0.108 | P = 0.177 | P = 0.129 | P = 0.262 |

| > 64 | 40 | |||||

| Histological type | ||||||

| Differentiated | 47 | P = 0.976 | P = 0.004 | P = 0.151 | P = 0.053 | P = 0.231 |

| Undifferentiated | 32 | |||||

| Depth of invade | ||||||

| Not invasion | 27 | P = 0.336 | P = 0.042 | P = 0.266 | P = 0.354 | P = 0.555 |

| Invasion | 40 | |||||

| Clinical stage | ||||||

| Stage I + II | (22 + 11) | P = 0.075 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.139 | P = 0.018 | P = 0.863 |

| Stage III + IV | (20 + 26) | |||||

| Ki67 (median) | ||||||

| Low | 39 | P = 0.791 | P = 0.197 | P = 0.567 | P = 0.401 | P = 0.512 |

| High | 40 | |||||

| Apop Tag (median) | ||||||

| Low | 39 | P = 0.421 | P = 0.070 | P = 0.0020 | P = 0.408 | P = 0.099 |

| High | 40 |

None of the investigated clinicopathological parameters showed a statistically significant correlation with the expression of other types of survivin variants besides survivin-2B.

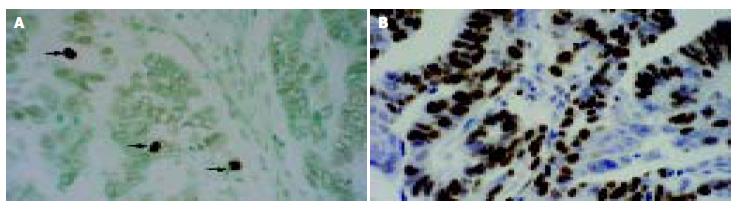

Apoptotic cells and bodies were detected in all cases of gastric carcinoma tested (Table 1, Figure 4A). The mean AI was 1.07% (SD, 0.41%; range, 0.38%-2.38%) with a median of 0.95%. The mean AI in survivin-△Ex3-low expression samples was significantly higher than that in survivin-△Ex3-high expression samples (P = 0.02, Table 1, P = 0.028, χ2 test, Table 1). There was no correlation between apoptotic index and clinicopathological parameters described. Spearman’s rank correlation test demonstrated a significant negative correlation between apoptotic index and expression level of survivin-△Ex3 (Г = -0.257, P = 0.022).

Proliferative cells were detected by intense nuclear immunoreactivity to the Ki-67 antigen, as illustrated in Figure 4B. The mean proliferative index (PI) in gastric tumors tested was 48.46% (SD, 9.54%; range, 28.49%-82.98%) with a median of 46.87%. No significant relationship was identified between PI of tumor cells and clinicopathological parameters, as demonstrated in Table 1. In addition, no significant association was found between PI and any type of survivin variants.

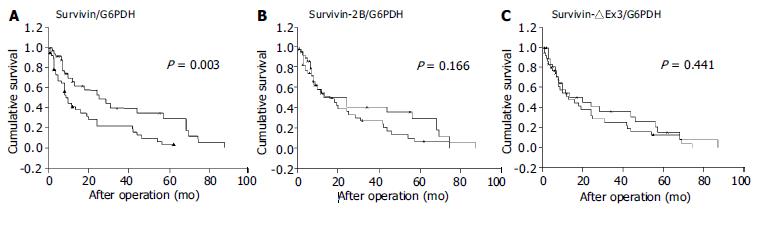

Postoperative survival of the 79 gastric cancer patients was analyzed according to the expression level of survivin variants. Results are shown in Figure 5. Each survivin variant value was divided by the median value. The survival curve of patients with high-survivin expression was significantly lower than that of those with low-survivin expression (P = 0.003, log-rank test). No prognostic significance for either survivin-2B or survivin-△Ex3, however, was found in the current study.

In this study, the prognostic significance of the expression of three survivin splicing variants in gastric carcinoma was examined for the first time. Interestingly, only increased wild-type survivin mRNA expression was prominently correlated with reduced survival time, whereas neither survivin-2B nor survivin-△Ex3 showed an association with prognosis. In accordance with recent studies, we did not find a correlation between mRNA expression levels of anti-apoptotic variants (survivin or survivin-△Ex3) and the investigated clinicopathological parameters[9,10]. There is no doubt, however, survivin plays a role in enhancing the malignant behavior of tumors. In cell culture systems, over-expression of survivin was consistently associated with inhibition of cell death[2]. Strong survivin mRNA expression showed chemo-radio resistance[11-13] and a correlation with recurrence in patients[14]. In retrospective trials, increased survivin mRNA or protein expression was reported to be a prognostic indicator of tumor progression in different types of human cancer[15-19]. Our observations further confirmed that survivin mRNA was a poor prognostic biomarker. This suggests that a relatively straightforward detection of survivin protein or mRNA in clinical patients may provide an initial marker of aggressive diseases, potentially requiring in-depth follow-up protocols or alternative treatment regimens in the future.

The notion that survivin inhibits apoptosis has been established, but the mechanism (s) by which this occurs has not been conclusively determined. The actual molecular interaction partners of survivin variants, however, have remained elusive[2]. Although there is a good agreement that deregulation of cell death/survival pathways contributes to malignant transformation, the potential predictive/prognostic impact of apoptosis regulatory molecules and AI has remained controversial[8]. This study failed to show the relationship between apoptotic index and survivin expression in gastric carcinoma although it was shown in previous[5,20] studies showed in gastric cancer that survivin expression was inversely correlated with apoptosis. These controversial findings were attributed in part to the dual function by which survivin regulates cell death and cell division. In recent studies, frameshift carboxyl terminus of survivin-△Ex3 was found to contain a bipartite localization signal, which mediates its strong nuclear accumulation and might interfere with degradation of survivin-△Ex3 protein by ubiquitin tagging. Survivin-△Ex3, therefore, could evade cell cycle-specific degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, known for survivin. In contrast, cytoplasm has been found to be the most probable location of both survivin and survivin-2B[21,22]. Other unique features in survivin-△Ex3 were also identified, including a mitochondrial localization signal and a BH2 domain, which might inhibit apoptosis by association with bcl-2, and suppress Caspase-3 activity by BIR-dependent pathway[23]. Consequently, survivin-△Ex3 may play a more crucial role in the regulation of apoptosis.

Although mRNA levels of survivin-2B and survivin-△Ex3 have been found in different tumors[3,10,24,25], little is known about the protein levels of endogenous survivin-2B and survivin-△Ex3, due to the lack of survivin variant-specific antibodies. Our results showed that a low mRNA expression level of survivin-2B was inversely correlated to the advanced (III + IV) stage, undifferentiated tumor histology and deep tumor invasion. There are at least two reasonable explanations for this finding. After losing its antiapoptotic potential, survivin-2B was hypothesized to be a naturally occurring antagonist of survivin from competitive binding to heterologous interaction partners, or from the formation of inactive survivin: survivin-2B heterodimers with respect to recently observed dimer formation of survivin[21]. Downregulation of survivin-2B might weaken its functional antagonism, and moreover, could permit the generation of more survivin or survivin-△Ex3 because three survivin variants come from the same pool of a hnRNA precursor. Thus, the decrease in survivin-2B may result in the development, invasion and anaplasia of carcinomas.

In addition, our data showed that all gastric carcinoma samples expressed wild-type survivin at a significant level compared to the matched normal gastric mucosa samples. Similarly, the expression of survivin-2B or survivin-△Ex3 was significantly elevated in carcinoma tissue. Among three survivin variants, survivin was the dominant transcript. In this regard, our results were consistent with those of two recent TR-PCR studies[10,26] on gastric cancer in which a few gastric mucosa samples (17%-23%) of the first-degree relatives also expressed survivin mRNA, but the normal control subjects did not. All these findings may help explain why survivin variants played important roles in the early stage of carcinogenesis of gastric cancer.

In summary, survivin mRNA is a poor prognostic biomarker and that non-antiapoptotic survivin-2B was correlated to tumor stage, histological type and depth of tumor invasion. Even more striking is the observation for the first time that neither survivin nor survivin-2B show a close association with the apoptosis index, as observed in survivin-△Ex3, although further experimental work is necessary to elucidate the functional properties of different splicing variants in more detail.

We thank Ms. Akiko Miyamoto and Drs. Takaharu Suga and Yoshiaki Tatsumi, Department of General and Gastroenterological Surgery, or Dr. Noda Naohiro, First Department of Pathology, Osaka Medical College for their excellent assistance throughout this investigation.

Edited by Wang XL Proofread by Xu FM

| 1. | Rudin CM, Thompson CB. Apoptosis and disease: regulation and clinical relevance of programmed cell death. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:267-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Altieri DC. Validating survivin as a cancer therapeutic target. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:46-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 931] [Cited by in RCA: 946] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mahotka C, Wenzel M, Springer E, Gabbert HE, Gerharz CD. Survivin-deltaEx3 and survivin-2B: two novel splice variants of the apoptosis inhibitor survivin with different antiapoptotic properties. Cancer Res. 1999;59:6097-6102. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Liu HF, Liu WW, Fang DC, Men RP. Expression and significance of proapoptotic gene Bax in gastric carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:15-17. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lu CD, Altieri DC, Tanigawa N. Expression of a novel antiapoptosis gene, survivin, correlated with tumor cell apoptosis and p53 accumulation in gastric carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1808-1812. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Nishi M, Omori Y, Miwa K. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma, First English edition. TOKYO: KANEHARA & CO., LTD 1995; . |

| 7. | Kawasaki H, Toyoda M, Shinohara H, Okuda J, Watanabe I, Yamamoto T, Tanaka K, Tenjo T, Tanigawa N. Expression of survivin correlates with apoptosis, proliferation, and angiogenesis during human colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer. 2001;91:2026-2032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kawasaki H, Altieri DC, Lu CD, Toyoda M, Tenjo T, Tanigawa N. Inhibition of apoptosis by survivin predicts shorter survival rates in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5071-5074. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Mahotka C, Krieg T, Krieg A, Wenzel M, Suschek CV, Heydthausen M, Gabbert HE, Gerharz CD. Distinct in vivo expression patterns of survivin splice variants in renal cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2002;100:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Krieg A, Mahotka C, Krieg T, Grabsch H, Müller W, Takeno S, Suschek CV, Heydthausen M, Gabbert HE, Gerharz CD. Expression of different survivin variants in gastric carcinomas: first clues to a role of survivin-2B in tumour progression. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:737-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Asanuma K, Moriai R, Yajima T, Yagihashi A, Yamada M, Kobayashi D, Watanabe N. Survivin as a radioresistance factor in pancreatic cancer. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:1204-1209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ikeguchi M, Kaibara N. Changes in survivin messenger RNA level during cisplatin treatment in gastric cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2001;8:661-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kato J, Kuwabara Y, Mitani M, Shinoda N, Sato A, Toyama T, Mitsui A, Nishiwaki T, Moriyama S, Kudo J. Expression of survivin in esophageal cancer: correlation with the prognosis and response to chemotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2001;95:92-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Azuhata T, Scott D, Takamizawa S, Wen J, Davidoff A, Fukuzawa M, Sandler A. The inhibitor of apoptosis protein survivin is associated with high-risk behavior of neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1785-1791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ikeguchi M, Kaibara N. survivin messenger RNA expression is a good prognostic biomarker for oesophageal carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:883-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Adida C, Berrebi D, Peuchmaur M, Reyes-Mugica M, Altieri DC. Anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, and prognosis of neuroblastoma. Lancet. 1998;351:882-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Adida C, Haioun C, Gaulard P, Lepage E, Morel P, Briere J, Dombret H, Reyes F, Diebold J, Gisselbrecht C. Prognostic significance of survivin expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2000;96:1921-1925. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Chakravarti A, Noll E, Black PM, Finkelstein DF, Finkelstein DM, Dyson NJ, Loeffler JS. Quantitatively determined survivin expression levels are of prognostic value in human gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1063-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kamihira S, Yamada Y, Hirakata Y, Tomonaga M, Sugahara K, Hayashi T, Dateki N, Harasawa H, Nakayama K. Aberrant expression of caspase cascade regulatory genes in adult T-cell leukaemia: survivin is an important determinant for prognosis. Br J Haematol. 2001;114:63-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wakana Y, Kasuya K, Katayanagi S, Tsuchida A, Aoki T, Koyanagi Y, Ishii H, Ebihara Y. Effect of survivin on cell proliferation and apoptosis in gastric cancer. Oncol Rep. 2002;9:1213-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mahotka C, Liebmann J, Wenzel M, Suschek CV, Schmitt M, Gabbert HE, Gerharz CD. Differential subcellular localization of functionally divergent survivin splice variants. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1334-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rodríguez JA, Span SW, Ferreira CG, Kruyt FA, Giaccone G. CRM1-mediated nuclear export determines the cytoplasmic localization of the antiapoptotic protein Survivin. Exp Cell Res. 2002;275:44-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang HW, Sharp TV, Koumi A, Koentges G, Boshoff C. Characterization of an anti-apoptotic glycoprotein encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus which resembles a spliced variant of human survivin. EMBO J. 2002;21:2602-2615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hirohashi Y, Torigoe T, Maeda A, Nabeta Y, Kamiguchi K, Sato T, Yoda J, Ikeda H, Hirata K, Yamanaka N. An HLA-A24-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope of a tumor-associated protein, survivin. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1731-1739. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kappler M, Köhler T, Kampf C, Diestelkötter P, Würl P, Schmitz M, Bartel F, Lautenschläger C, Rieber EP, Schmidt H. Increased survivin transcript levels: an independent negative predictor of survival in soft tissue sarcoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2001;95:360-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yu J, Leung WK, Ebert MP, Ng EK, Go MY, Wang HB, Chung SC, Malfertheiner P, Sung JJ. Increased expression of survivin in gastric cancer patients and in first degree relatives. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:91-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |