Published online Oct 1, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i19.2919

Revised: October 28, 2003

Accepted: November 6, 2003

Published online: October 1, 2004

To present a patient diagnosed with pancreatic carcinoid that was extremely rare and produced an atypical carcinoid syndrome. We reported a 58-year old male patient who presented with long standing, prominent cervical lymphadenopathy and occasional watery diarrhea. Pathohistological and immunohistochemical examination of lymph node biopsy showed a metastatic neuroendocrine tumor, which was histological type A of carcinoid (EMA+, cytokeratin+, CEA-, NSE+, chromogranin A+, synaptophysin+, insulin-). Bone marrow biopsy showed identical findings. Primary site of the tumor was pancreas and diagnosis was made according to cytological and immunocytochemical analysis of the tumor cells obtained with aspiration biopsy of pancreatic mass (12 mm in diameter) under endoscopic ultrasound guidance. However, serotonin levels in blood and urine samples were normal. It is difficulty to establish the precise diagnosis of a “functionally inactive” pancreatic carcinoid and aspiration biopsy of pancreatic tumor under endoscopic ultrasound guidance can be used as a new potent diagnostic tool.

- Citation: Marisavljevic D, Petrovic N, Milinic N, Cemerikic V, Krstic M, Markovic O, Bilanovic D. An unusual presentation of “silent” disseminated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(19): 2919-2921

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i19/2919.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i19.2919

In 1907, Obendorfer applied the term “karzinoide” to describe a set of ileal tumors that behaved in a more benign manner than carcinomas. Since then, carcinoid tumors have been found to be relatively uncommon neuroendocrine tumors arising from neural crest cells known as “amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation cells” (APUD), which are derived from gut endoderm. Recent consensus meetings suggested that a more appropriate term “neuroendocrine tumor” should be used for all endocrine tumors of the digestive system, because these tumors derive from the diffuse neuroendocrine system[1]. Pancreas, mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract[2] and endocrine cells scattered in other endodermal sites (such as thyroid, lung, biliary tree and the urogenital tract) belong to APUD system. Neuroendocrine tumors can be subclassified into those with or without clinical syndromes and are termed “functionally active” and “functionally inactive” pancreatic carcinoid, respectively[3]. Carcinoid of the pancreas is extremely rare and the diagnosis may puzzle physicians and pathologists[4]. Pancreatic carcinoids produce an atypical carcinoid syndrome, skin flushing was reported in only 34%, the main symptom is pain, followed by diarrhea and weight loss.

We hereby described a patient with disseminated “functionally inactive” neuroendocrine tumor who presented with lymph node metastases, but without characteristic symptoms of carcinoid syndrome. The primary site of the tumor was pancreas.

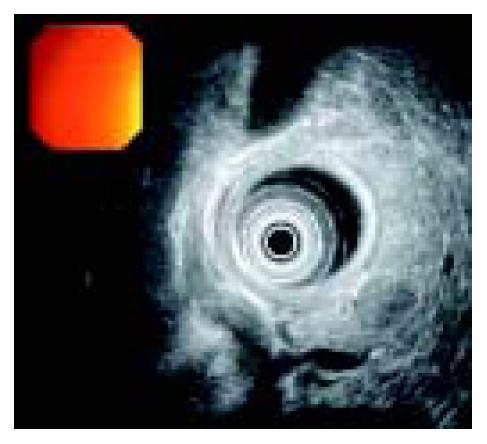

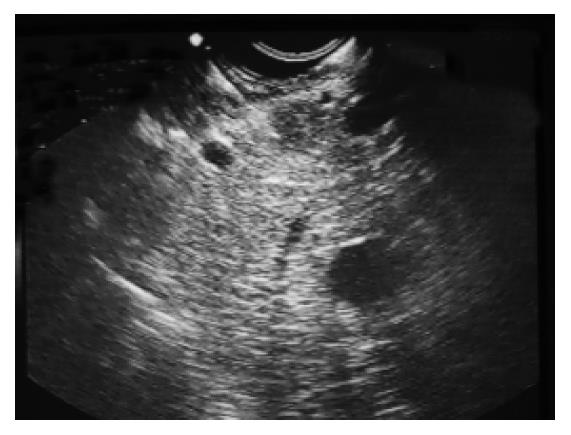

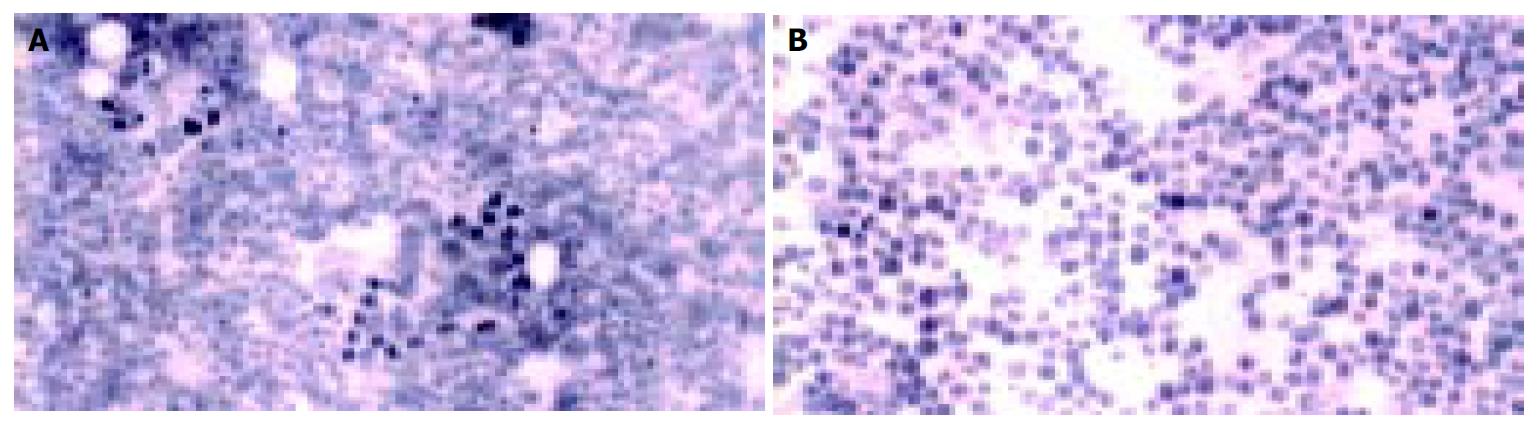

A 58-years old male was admitted to Hematology Department in June 2001 with complaint of a left anterior neck mass and occasional massive, watery diarrhea. The patient noticed slow enlargement of neck mass for two years prior to admission, and also stated that in the last 12 mo he had episodes of diarrhea 1-2 times/wk. Diarrhea was massive and watery (up to 1 L/d) without visible blood or mucous and usually self-limited. Diarrhea was not associated with abdominal pain, tenesmus or with food intake. He lost 5 kg in 3-4 mo, inspite of good appetite. His previous medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination showed a left anterior neck mass (7 cm × 6 cm in diameter), painless and movable in all directions. Chest X-ray showed paratracheal infiltrate. On bronchoscopy, external compression on posterior and lateral tracheal walls was seen. CT of chest showed enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes (up to 40 mm). CT of abdomen showed an enlarged pancreatic head (46 mm) with a mild hypodense area (12 mm in diameter). Pathohistological findings of tissue samples from the neck tumor (cuneiform biopsy) and bone marrow (trephine biopsy) were identical, namely a metastatic neuroendocrine tumor, which was histological type A of carcinoid. Immunophenotyping of cells from the neck tissue sample showed well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (APUDOMA) that was immunostained as follows: EMA+, cytokeratin 8+, CEA-, NSE+, chromogranin A+, synaptophysin+, insulin-. In an effort to find the primary site of APUDOMA, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, endoscopic enteroscopy, colonoscopy, small bowel barium enema, radial endoscopic ultrasound (radial EUS - Olympus device) were done (Figure 1). Ultrasound (linear EUS) guided aspiration biopsy of the pancreatic mass was performed (Figure 2). Cytological examination showed solid nodular nests of small uniform, epitheloid cells of dense heterochromatin. Immunocytochemical analysis revealed groups of epithelial cells with positive cytoplasmatic staining on NSE and chromogranin A that implied on tumor with neuroendocrine differentiation (Figure 3). Pathohistological examination of aspiration liver biopsy was normal, excluding possible liver micro-metastasis. To exclude MEN syndrome, X-ray and MRI of sellar region as well as thyroid US were done and all tests were normal. On 2D ultrasound the right heart was anatomically and functionally within normal limits. Blood count and biochemistry were normal except for occasional hypokalemia and mild hypoproteinaemia (with proportional decrease in all electrophoresis fractions). CEA was significantly increased (535.5 ng/mL), but pancreatic tumor marker (CA 19-9) and alpha-feto protein were within normal limits. Serotonin level in blood and urine was normal (0.25 mmol/L and 359 mmol/24 h, respectively). 5-HIAA in the urine sample was increased (84 µmol/L, reference range: 10.4-41.6 µmol/L). Periodical diarrhea was controlled with loperamid and oral potassium supplementation. During hospitalization, patient developed urinary retention. Rectal examination and US revealed a prostatic adenoma (size 44 mm × 54 mm × 54 mm, 60 g weight) with normal values of prostate serum antigen. Transvesical adenectomy was performed, and pathohystologic findings confirmed it to be an adenoma. Postoperative period was complicated with prolonged wound healing and vesicodermal fistula. The patient also had changes of mental status, but CT of the head did not show any abnormalities. The patient was regularly followed up. In December 2001 he was doing well, still complaining of frequent diarrhea and minimal enlargement of the neck mass. Blood tests continued to show hypoproteinemia and hypokalemia, easily controlled with potassium supplementation. However, the patient died in January 2002 at home. His family recorded no particular circumstances related to his death.

Functionally active neuroendocrine tumors are presented with clinical symptoms because of excessive hormone release from the tumor cells as in insulinoma, gastrinoma, VIPoma, glucagonoma and carcinoid syndrome[5]. Carcinoid tumors, except those originating from rectum, produced a variety of endocrine substances, the most frequent one was serotonin and kallikrein[6-8]. Carcinoid syndrome that includes diarrhea, flushing, wheezing, and right-sided heart disease[9] is caused by systemic serotonin release. Less than 10% of carcinoids had some of these symptoms[10]. Explanation is efficient hepatic metabolism of vasoactive amines, and that is also the reason why carcinoid syndrome rarely occurred in the absence of liver metastasis. Exceptions are circumstances in which venous blood from a large tumor was drained directly into systemic circulation[11].

Functionally inactive neuroendocrine tumors can be diagnosed in several ways: a) accidentally during routine ultrasonography performed for unexplained abdominal complaints, b) when a large tumor of the pancreatic head is causing obstruction and consequently extrahepatic jaundice, c) when a patient presents with abdominal pain secondary to bowel pseudo-obstruction, and d) as complications of the tumor such as bleeding. Our patient had occasional diarrhea that was not significant (less than 1L per day). Besides he had no other symptoms, and his blood tests failed to show any endocrine abnormalities. Histopathological and imunohistochemical analyses of the tissue sample from the neck mass showed a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor, which was histological type A of carcinoid (APUDOMA). At the time of diagnosis, metastatic disease of cervical and mediastinal lymph nodes, and bone marrow already existed which was confirmed by histopathological finding. Aspiration liver biopsy was done to exclude micro-metastases, that otherwise could not be visualized by imaging methods, and the result was negative. Primary site of the tumor was unknown. Because the most frequent localization of carcinoid was in the gastrointestinal tract, it was explored in whole, but primary tumor was not found. Aspiration biopsy of the pancreatic mass under endoscopic ultrasound guidance was done for the first time in Yugoslavia. Immunocytochemical report confirmed that the pancreatic mass was the primary site that only occurred in 2%-3% of all cases[4,12,13]. Also, carcinoid tumors up to 1 cm rarely metastaze, but that was not the case with our patient.

The slow growth rate and late invasion of adjacent organs rendered local resection of pancreatic carcinoid tumor possible, but the high incidence of distant metastases (69%) prevented long-term survival in the majority of patients[4]. Diarrhea with hypokalemia and hypoproteinemia, as a manifestation of carcinoid syndrome in this case could be explained by increased release of vasoactive substances most probably from the extensive metastasis in the bone marrow, and lymph nodes. However, these metabolic abnormalities were well controlled and could not be the main cause of his death.

In summary, atypical presentation in this and other reported cases of pancreatic carcinoids suggests that metastatic potential of functionally inactive neuroendocrine cells is originated from the pancreas.

Edited by Wang XL and Xu JY Proofread by Xu FM

| 1. | Polak JM. Diagnostic histopathology of neuroendocrine tumors. Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone 1993; . |

| 2. | Solcia E, Capella C, Riocca R. Disorders of the endocrine system. Pathology of the gas-trointestinal tract. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins 1998; 295-322. |

| 3. | Arnold R. Diagnosis and Management of Neuroendocrine Tumors. 8th United European Gastroenterology Week, Brussels, Belgium. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins 2001; . |

| 4. | Maurer CA, Baer HU, Dyong TH, Mueller-Garamvoelgyi E, Friess H, Ruchti C, Reubi JC, Büchler MW. Carcinoid of the pancreas: clinical characteristics and morphological features. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1109-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Eriksson B, Oberg K, Stridsberg M. Tumor markers in neuroendocrine tumors. Digestion. 2000;62 Suppl 1:33-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sweeney JF, Rosemurgy AS. Carcinoid Tumors of the Gut. Cancer Control. 1997;4:18-24. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Shebani KO, Souba WW, Finkelstein DM, Stark PC, Elgadi KM, Tanabe KK, Ott MJ. Prognosis and survival in patients with gastrointestinal tract carcinoid tumors. Ann Surg. 1999;229:815-21; discussion 822-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kulke MH, Mayer RJ. Carcinoid tumors. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:858-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 647] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Anderson AS, Krauss D, Lang R. Cardiovascular complications of malignant carcinoid disease. Am Heart J. 1997;134:693-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vinik AI, Thompson N, Eckhauser F, Moattari AR. Clinical features of carcinoid syndrome and the use of somatostatin analogue in its management. Acta Oncol. 1989;28:389-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Onaitis MW, Kirshbom PM, Hayward TZ, Quayle FJ, Feldman JM, Seigler HF, Tyler DS. Gastrointestinal carcinoids: characterization by site of origin and hormone production. Ann Surg. 2000;232:549-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Varshney S, Johnson CD. Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2000;19:181-183. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Jensen RT. Pancreatic endocrine tumors: recent advances. Ann Oncol. 1999;10 Suppl 4:170-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |