Published online Jul 1, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i13.1995

Revised: December 28, 2003

Accepted: January 8, 2004

Published online: July 1, 2004

AIM: To evaluate the impact of advanced age on outcome after hepatectomy, gastrectomy and pancreatoduodenectomy.

METHODS: Two hundreds and eleven patients undergone hepatectomy, gastrectomy and pancreatoduodenectomy from January 1998 to September 2002 were analyzed retrospectively. Clinicopathologic features and operative outcome of 83 patients aged 65 years or more were compared with that in 128 younger patients aged less than 65 years.

RESULTS: The nutritional state, such as pre-operation level of serum albumin and hemoglobin in the older patients was poorer than that in the younger patients. The older patients had higher comorbidities than the younger patients (48.2% vs 15.6%). No significant difference was observed in perioperative mortality, and complication rate between the older and younger patients (2.4% vs 1.6% and 22.9% vs 20.3%, respectively). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that pancreatoduodenectomy, hepatectomy with resection of more than 2 segments and comorbidities were independent predictors of postoperative complication, whereas age was not (P = 0.3172).

CONCLUSION: It is safe for patients aged 65 years or more to undergo hepatic, pancreatic and gastric resection if great care is taken during perioperative period.

- Citation: Wu YL, Yu JX, Xu B. Safe major abdominal operations: Hepatectomy, gastrectomy and pancreatoduodenectomy in elder patients. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(13): 1995-1997

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i13/1995.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i13.1995

The number and proportion of the elderly in our population have increased progressively as a result of increased life expectancy. The population over the age of 65 years is growing at the fastest rate than any other age groups[1]. But surgery for potentially curable disease frequently leaves elderly patients numerically de-represented[2]. Worrying about surgical risks and morbidity may be one reason accounting for this phenomenon. There are different opinions about whether elderly surgical patients have poor outcome. Some studies suggested that elderly surgical patients had high morbidity and mortality[3,4]. Other reports showed that there was no significant difference in the rate of complications and death between the older and the younger surgical patients[5,6]. Two hundreds and eleven patients undergone major abdominal operations, including hepatectomy, gastrectomy and pancreatoduodenectomy in recent 5 years were analyzed retrospectively to see whether the older patients face more risks than younger patients.

Two hundreds and eleven patients who underwent hepatectomy, gastrectomy or pancreatoduodenectomy in our hospital from January 1998 to September 2002 were studied retrospectively. The patients were divided into two groups: older group (age ≥ 65 years) and younger group (age < 65 years). The patients’ age and sex, diagnosis, comorbidities, preoperative laboratory values, type of operation, clinical and pathologic characteristics of local lesion, postoperative complications and death, operative blood loss and transfusion, relaparotomy, length of hospital stay were obtained from the operative records and medical notes. The primary carcinoma was divided into different stages according to TNM staging system defined by Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC, 1997). The patients were considered to have comorbidity when treatment was required in additional organ systems. Complications were defined by the classification proposed by Clavien et al[7]. Because grade I complications (minor and were likely to resolve spontaneously) were difficult to collect due to retrospective audits, only grade IIa complications (requiring drug for treatment), grade IIb complications (requiring reoperation or invasive procedure), grade III complications (events with residual or lasting disability including organ resection), grade IV complications (death as a result of any complication) were included in this study. Mortality was defined as death from any cause within 30 days of the operation.

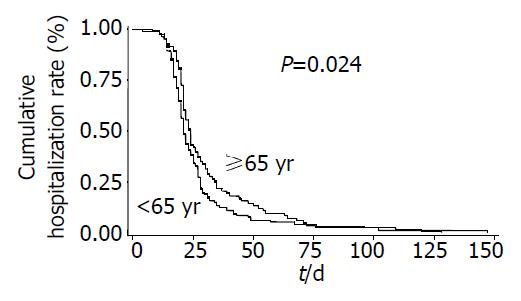

Data were analyzed with the SAS 8.0 statistical software. Differences were analyzed with the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for group contingency analysis and the Student’t test and Mann-Whitney non-parametric test for continuous variables. Using logistic regression, the influence of different variables on the complication was studied. Length of hospital stay of the two groups was compared with a nonparametric product-limit method analogous to a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

0f the 211 patients, 150 cases were men and 61 cases were women. The median age was 60 years (range, 18 to 88).

The older group consisted of 83 patients, including 51 cases (≥ 65 years), 21 cases (> 70 years), 6 cases (> 75 years), and 5 cases (> 80 years). Diagnosis included primary hepatic carcinoma (31 cases), hepatic adenoma (1 case), hepatic chronic granuloma (1 case), metastatic cancer in liver (5 cases), gastric carcinoma (30 cases), gastric carcinoid (1 case), pancreatic carcinoma (4 cases), periampullary cancer (8 cases), and chronic pancreatitis (2 cases).

The younger group consisted of 128 patients. Diagnosis included primary hepatic carcinoma (45 cases), hepatic malignant stroma (1 case), focal nodular hyperplasia of liver (1 case), metastatic cancer in liver (1 case), gastric carcinoma (37 cases), gastric ulcer (1 case), gastric malignant stoma (1 case), pancreatic carcinoma (15 cases), periampullary cancer (23 cases), chronic pancreatitis ( 2 cases), and benign biliary stricture (1 case).

No difference in stage of primary cancer was seen between the older group and younger group, but the levels of serum albumin and hemoglobin in older group were lower than those in younger group (Table 1). A 48.2% of total patients in older group had one or more comorbidities, which was significantly higher than that in younger group (15.6%). There was no difference in the constitution of operative procedure in the older and younger group. Median operative blood loss and transfusion were similar in both groups (500 mL vs 500 mL and 2 units vs 2 units, Table 1).

| Clinicopathologic | Younger group | Older group | P value |

| Features | (< 65 yr) | (≥ 65 yr) | |

| Age (median) | 52 | 69 | |

| Gender (n) | 0.21421 | ||

| Male | 87 | 63 | |

| Female | 41 | 20 | |

| Diagnosis (n) | 0.11052 | ||

| Liver | |||

| Hepatic carcinoma | 45 | 31 | |

| Others | 3 | 7 | |

| Stomach | |||

| Gastric carcinoma | 37 | 30 | |

| Others | 2 | 1 | |

| Pancrea | |||

| Pancreatic carcinoma | 15 | 4 | |

| Periampullary carcinoma | 23 | 8 | |

| Others | 3 | 2 | |

| Serum albumin | 3.84 ± 0.46 | 3.65 ± 0.50 | 0.00453 |

| (mean ± SD, g/dL) | |||

| Hemoglobin | 12.05 ± 2.39 | 11.16 ± 2.33 | 0.00823 |

| (mean ± SD, g/dL) | |||

| Stage of primary cancer (n) | 0.56581 | ||

| I | 18 | 12 | |

| II | 32 | 13 | |

| III | 53 | 34 | |

| IV | 17 | 13 | |

| Comorbidity | 15.6% (20/128) | 48.2% (40/83) | < 0.00011 |

There was no apparent difference in complication rates between the older and younger group (22.9% vs 20.3%, Table 2). The most common complications were wound infection. Other complications included pneumonia, bile leak, pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, gastrointestinal fistula, cerebrovascular accident, abdominal bleeding, gastric bleeding, DIC, hepatic encephalopathy, pleural effusion, and renal failure. Two patients (2.4%) were re-operated because of gastric bleeding and bile leak in older group. Three patients (2.3%) were re-operated because of intestinal fistula, abdominal bleeding and bile leak in younger group. There was no significant difference in the rate of the re-operation between the two groups (Table 2). In older group, one patient died of DIC and severe metabolic acidosis 4 d after operation, another patient died of pneumonia 24 d after operation. In younger group, two patients died of abdominal hemorrhage and hepatic encephalopathy 13 and 27 d, respectively, after operation. The older patients had almost same perioperative mortality rate as the younger patients (2.4% and 1.6%, respectively). The median hospital stay was 24 d (range, 8 to 147 d) in the older group, which was significantly longer than that in the younger group (median, 21 d, and range, 4 to 128 d) (Figure 1).

| Therapeutic characteristics | Younger group (< 65 yr) | Older group (≥ 65 yr) | P value |

| Operative procedures | 0.17081 | ||

| Hepatectomy ≤ 2 segments | 26 | 23 | |

| Hepatectomy > 2 segments | 22 | 15 | |

| Gastrectomy-total/proximal | 13 | 11 | |

| Gastrectomy-distal | 26 | 20 | |

| Pancreatoduodenectomy | 41 | 14 | |

| Operative blood loss (median, mL) | 500 (100-20000) | 500 (50-3500) | 0.64803 |

| Operative blood transfusion (median, units) | 2 (0-36) | 2 (0-13) | 0.33953 |

| Rate of complications | 20.3% (26/128) | 22.9% (19/83) | 0.65501 |

| Reoperative rate | 2.3% (3/128) | 2.4 % (2/83) | 1.00002 |

| Perioperative mortality (within 30 d) | 1.6% (2/128) | 2.4 (2/83) | 0.64702 |

| Hospital length of stay (median, d) | 21 (4-128) | 24 (8-147) | 0.02414 |

The multivariate analysis by a stepwise logistic regression model identified three independent significant variables for postoperative complications in the both groups: pancreatoduodenectomy, hepatectomy with resection of more than 2 segments and comorbidities. Sex, reasons of operations, serum albumin, hemoglobin did not influence the morbidity as an independent factor. Calendaric age (in years) was not an independent predictor of complication (P = 0.3172) (Table 3).

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value |

| Pancreatoduodenectomy | 3.7736 | 1.7699-8.0145 | 0.0006 |

| Hepatectomy > 2 segments | 1.0858 | 1.0060-1.1834 | 0.0334 |

| Comorbidity | 3.2787 | 1.5361-6.9930 | 0.0021 |

| Age (as continuous variable) | 1.0173 | 0.9833-1.0537 | 0.3172 |

Our study suggests that there is no difference between the older patients and the younger patients in postoperative morbidities and mortalities. Similar results have been reported by others. Hodul et al[6] studied in 122 patients with pancreatoduodenectomy, including 48 patients aged over 70 years, and reported no significant difference between older group and younger group comparing the rate of complications, such as wound infection, abdominal abscess, pancreatic leak, and so on. A retrospective study carried out on 97 patients with a gastric tumor measuring 10 cm or more in diameter showed age was not the influencing factor of frequency of complications[5]. Furthermore, analysis of extended hepatectomy (more than four liver segments) demonstrated age was not a contributor to in-hospital mortality[8].

The improvement in perioperative management was a vital reason for reducing the morbidity and mortality[9]. Developed guidelines for perioperative care may contribute the safety of operation for the elderly, for example, less use of nasogastric tubes can decrease the pulmonary complications, routine drainage being avoided in most cases or limited to a short period can facilitate early mobilization[10]. Preoperative assessment of elderly and formulation of an effective anesthetic plan according the “individual principle” can decrease the risks of anesthesia[11]. The surgeon’s skill was enhanced due to specialization and made the major abdominal operation become safety. Special team including surgeons, physicians, anesthetists and nurses for unstable elderly patients can decrease the morbidity and mortality[12]. The environment of operation room[13] was improved, the operative instruments were updated, which could attenuate the stress of an operation. Positive and effective treatment in surgical intensive care unit (SICU) helps elderly patients live through the crisis after operation.

Older patients need more perioperative care. First, older patients have more comordities require to manage than younger patients. Blair et al[14] reported older cases had more comorbidities than the younger (49% vs 25%) in a series of 179 patients undergone gastrectomy and pancreatectomy. In our study, nearly half of older patients had one or more comorbidities, which were significantly higher than that in younger patients. Second, the nutrition of older patients is poorer than younger patients. Our study showed the level of serum albumin and hemoglobin in older group was lower than younger group. More comorbidities and poorer nutrition mean the older patients need more waiting time for operation and more time for postoperative management, which lead more length of hospital stay in the older cases. Thus, the median hospital stay was longer significantly in older group longer than that in younger group in our study.

In this study, the level of serum albumin and hemoglobin were not the independent predictors for complications, suggesting that short-term nutritional support before operation could improve the nutritional status and reduce the risks of the surgery and anesthesia[15]. Comorbidity was an independent factor for complication in our study because the comorbidity could not be controlled in short-term. Comorbidity must be treated during perioperative period, which is a positive measure to reduce perioperative morbidity and mortality.

The patients with complex major operation should receive more perioperative care. Pancreatoduodenectomy and hepatectomy with resection of more than 2 segments were independent predictors of complication in our study. The result was supported by more recent reports. Jarnagin et al[16] studied in 1803 consecutive cases with hepatic resection over the past decade, and reported that the number of hepatic segments resected and operative blood loss were the independent predictors of both perioperative morbidity and mortality. So, the authors figured out that the major operation has more complications than minor operation[16].

In conclusion, the present data suggest that advanced age does not predict high morbidity and mortality after major abdominal operations. Surgeons should not advise against an operation just because the patient is old.

Edited by Kumar M Proofread by Xu FM

| 1. | Etzioni DA, Liu JH, Maggard MA, Ko CY. The aging population and its impact on the surgery workforce. Ann Surg. 2003;238:170-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 563] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pavlidis TE, Galatianos IN, Papaziogas BT, Lazaridis CN, Atmatzidis KS, Makris JG, Papaziogas TB. Complete dehiscence of the abdominal wound and incriminating factors. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:351-354; discussion 355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saghir JH, McKenzie FD, Leckie DM, McCourtney JS, Finlay IG, McKee RF, Anderson JH. Factors that predict complications after construction of a stoma: a retrospective study. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:531-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yasuda K, Shiraishi N, Adachi Y, Inomata M, Sato K, Kitano S. Risk factors for complications following resection of large gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:873-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hodul P, Tansey J, Golts E, Oh D, Pickleman J, Aranha GV. Age is not a contraindication to pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am Surg. 2001;67:270-275; discussion 270-25;. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Clavien PA, Sanabria JR, Strasberg SM. Proposed classification of complications of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1992;111:518-526. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Melendez J, Ferri E, Zwillman M, Fischer M, DeMatteo R, Leung D, Jarnagin W, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Extended hepatic resection: a 6-year retrospective study of risk factors for perioperative mortality. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:47-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Beliveau MM, Multach M. Perioperative care for the elderly patient. Med Clin North Am. 2003;87:273-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002;183:630-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1195] [Cited by in RCA: 1152] [Article Influence: 50.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Muravchick S. Preoperative assessment of the elderly patient. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2000;18:71-89, vi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Demetriades D, Sava J, Alo K, Newton E, Velmahos GC, Murray JA, Belzberg H, Asensio JA, Berne TV. Old age as a criterion for trauma team activation. J Trauma. 2001;51:754-756; discussion 754-756;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jin F, Chung F. Minimizing perioperative adverse events in the elderly. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:608-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Blair SL, Schwarz RE. Advanced age does not contribute to increased risks or poor outcome after major abdominal operations. Am Surg. 2001;67:1123-1127. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Cohendy R, Gros T, Arnaud-Battandier F, Tran G, Plaze JM, Eledjam J. Preoperative nutritional evaluation of elderly patients: the Mini Nutritional Assessment as a practical tool. Clin Nutr. 1999;18:345-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Ben-Porat L, Little S, Corvera C, Weber S, Blumgart LH. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1,803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg. 2002;236:397-406; discussion 406-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1148] [Cited by in RCA: 1074] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |