Copyright

©The Author(s) 2025.

World J Gastroenterol. Feb 7, 2025; 31(5): 99913

Published online Feb 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i5.99913

Published online Feb 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i5.99913

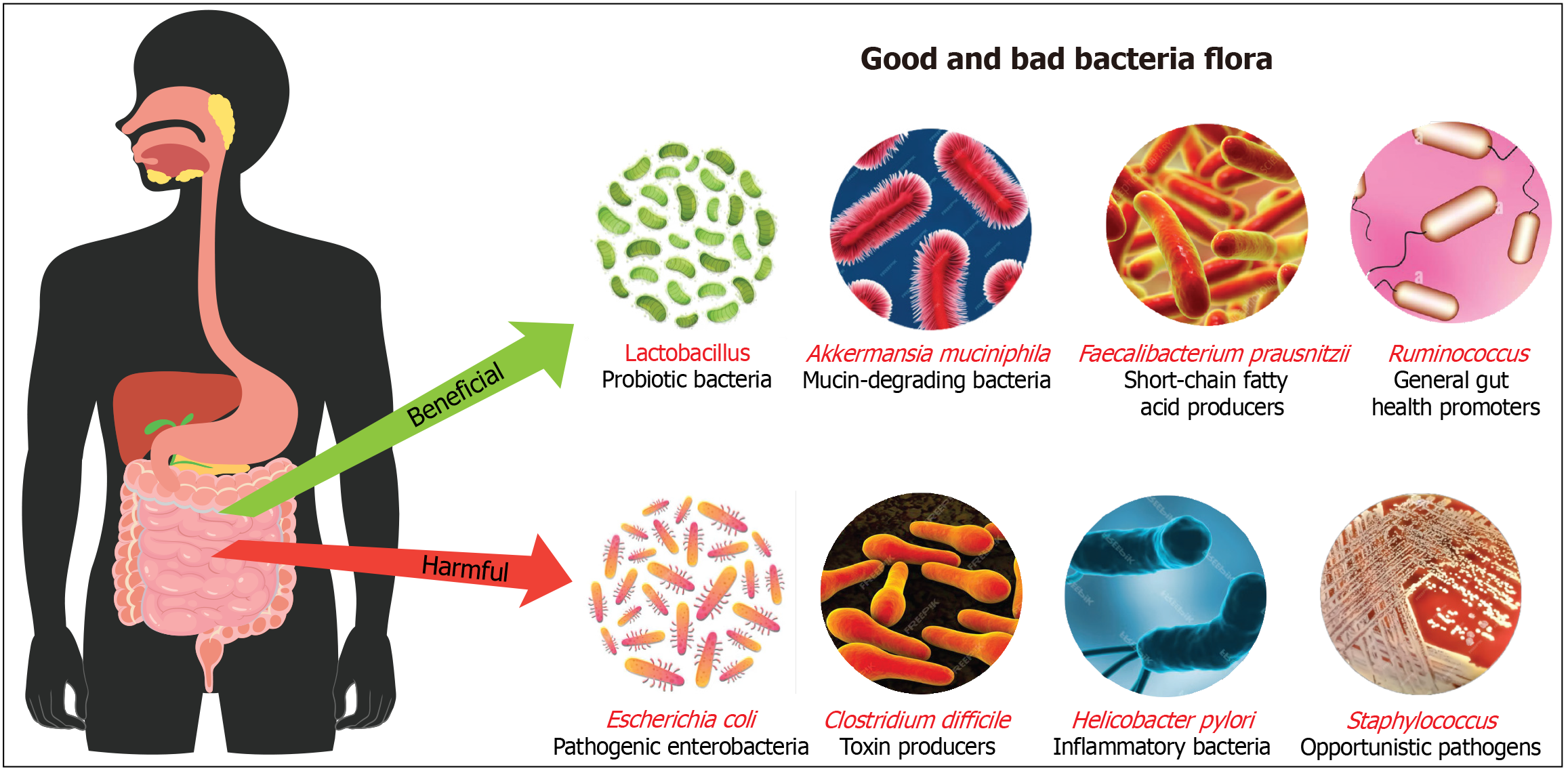

Figure 1 Illustration to distinguish between beneficial and harmful gut bacteria.

Beneficial bacteria include Lactobacillus, which are probiotics supporting digestion and immunity; Akkermansia muciniphila, which maintains gut lining integrity; Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, short-chain fatty acid producers with anti-inflammatory effects; and Ruminococcus, which aid in digesting complex carbohydrates. In contrast, harmful bacteria such as Escherichia coli can cause infections, Clostridium difficile produce toxins linked to severe diarrhea, Helicobacter pylori are associated with stomach ulcers, and Staphylococcus can be opportunistic pathogens. This highlights the critical role of a balanced microbiome in health maintenance and disease prevention.

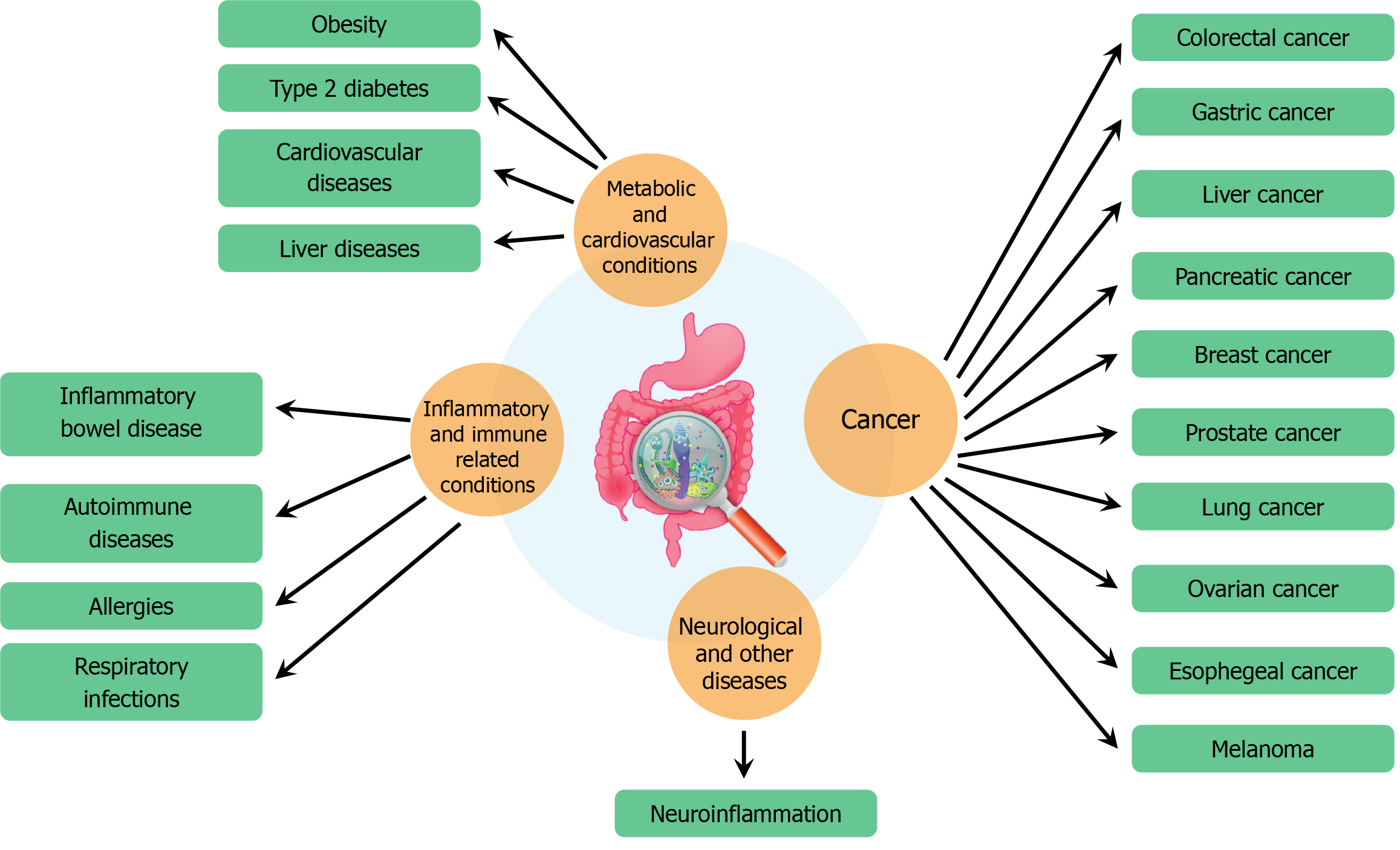

Figure 2 The relationship between human health and various diseases.

It highlights how poor gut health is linked to a range of conditions across different categories. Metabolic and cardiovascular conditions associated with gut health include obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and liver diseases. Inflammatory and immune-related conditions affected by gut health include inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune diseases, allergies, and respiratory infections. Gut health also plays a role in the development of cancer, with potential links to colorectal, gastric, liver, pancreatic, breast, prostate, lung, ovarian, esophageal cancers, and melanoma. Additionally, gut health is connected to neurological and other diseases, notably through neuroinflammation, emphasizing the extensive impact of gut microbiota on overall health.

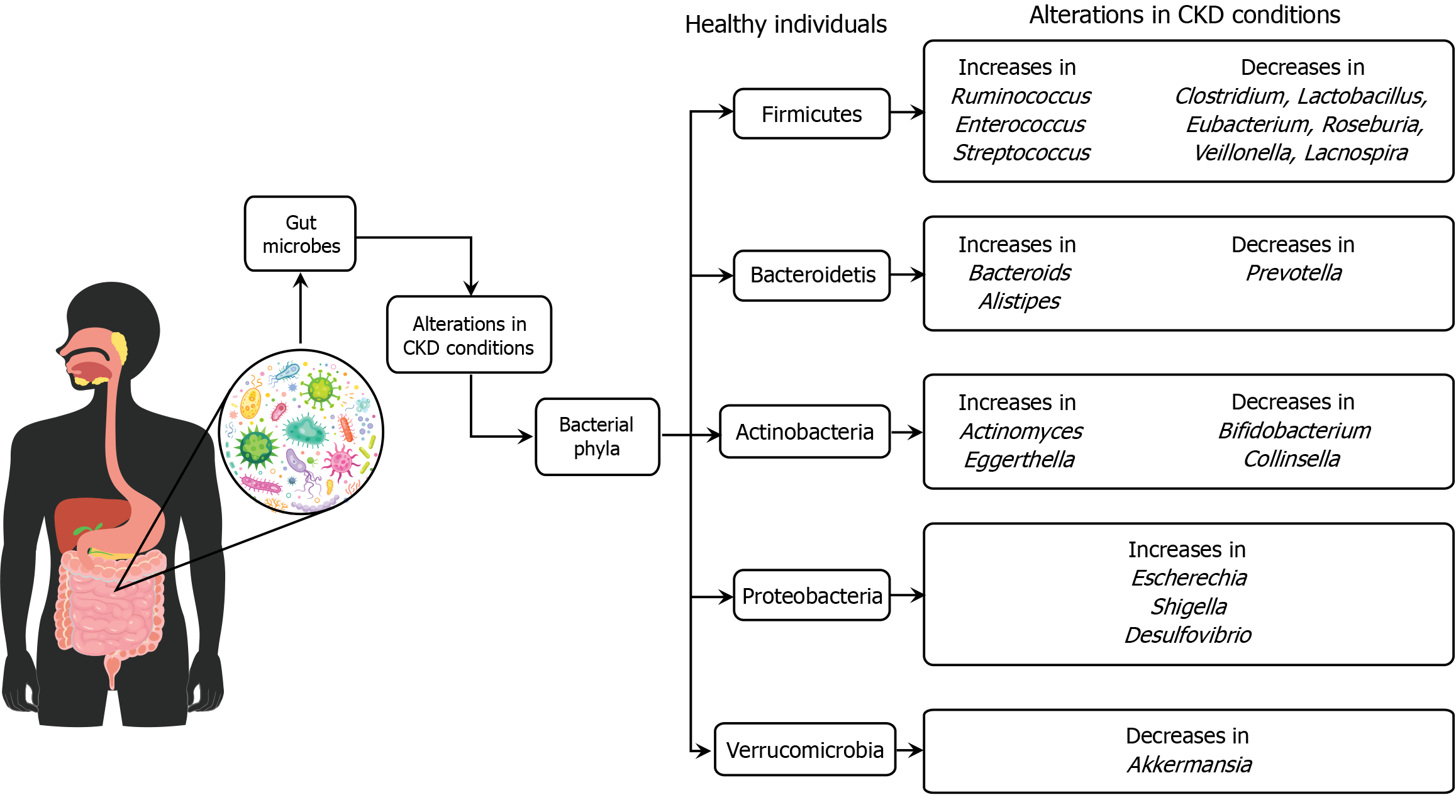

Figure 3 The alterations in gut microbiota are associated with chronic kidney disease conditions compared to healthy individuals.

In chronic kidney disease, there is a notable shift in the abundance of various bacterial phyla. Specifically, certain bacteria, such as Ruminococcus and Enterococcus from the Firmicutes phylum, are increased, while beneficial bacteria like Clostridium and Lactobacillus are decreased. Similar patterns are observed in other phyla, with increases in some bacteria and decreases in others, indicating a state of dysbiosis. This microbial imbalance is important as it may influence chronic kidney disease progression and related complications, highlighting the role of gut microbiota in disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. CKD: Chronic kidney disease.

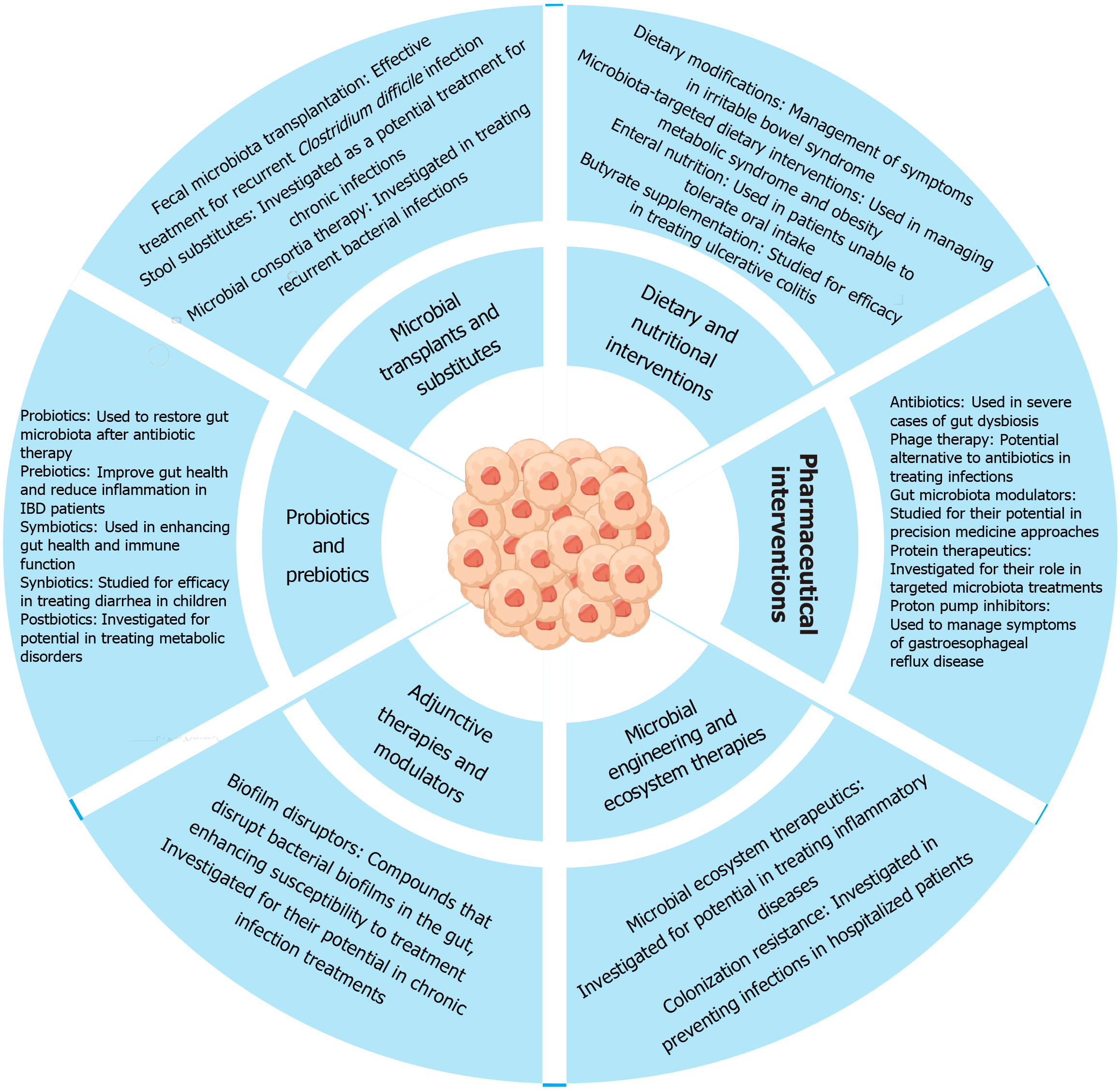

Figure 4 Therapeutic strategies aimed at improving gut health through different interventions.

The section on “Microbial transplants and substitutes” highlights the use of fecal microbiota transplantation stool substitutes, and microbial consortia for treating recurrent infections and metabolic disorders. “Probiotics and prebiotics” are emphasized for restoring and enhancing gut microbiota, improving gut health, and reducing inflammation, with specific applications for inflammatory bowel disease and metabolic disorders. “Dietary and nutritional interventions” include dietary modifications, microbiota-targeted diets, enteral nutrition, and butyrate supplementation for managing conditions like irritable bowel syndrome and ulcerative colitis. The “Pharmaceutical interventions” segment lists antibiotics, phage therapy, gut microbiota modulators, protein therapeutics, and proton pump inhibitors for treating dysbiosis and other gut-related conditions. “Adjunctive therapies and modulators” feature biofilm disruptors for treating chronic infections, while “Microbial engineering and ecosystem therapies” focus on microbial ecosystem therapeutics and colonization resistance to prevent infections and manage inflammatory diseases.

- Citation: Paul JK, Azmal M, Haque ASNB, Meem M, Talukder OF, Ghosh A. Unlocking the secrets of the human gut microbiota: Comprehensive review on its role in different diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(5): 99913

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i5/99913.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i5.99913