Copyright

©The Author(s) 2025.

World J Gastroenterol. May 21, 2025; 31(19): 106814

Published online May 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i19.106814

Published online May 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i19.106814

Figure 1 Endoscopic diagnosis of rectal neuroendocrine tumors.

A and B: The rectal neuroendocrine tumor typically appears as a small, yellowish, and subepithelial tumor-like lesion without surface change under white light or narrow band imaging as shown in case 1; C and D: For lesions with more significant elevation, there may be enlarged surface pit openings, but the overall shape remains unchanged, as seen in case 2; E and F: As the lesion grows larger, central depression may develop, accompanied by dilated micro-vessels, as illustrated in case 3.

Figure 2 Endoscopic intermuscular dissection in a rectal neuroendocrine tumor.

A: The lesion from case 2 (Figure 1C and D) was treated with intermuscular dissection. After circumferential incision, traction was applied with clips and a loop; B and C: During dissection, the circular muscle layer was carefully removed till the outer longitudinal muscle was fully exposed; D: Clips were used to close the mucosal defect.

Figure 3 Endoscopic full-thickness dissection in a 15-mm rectal neuroendocrine tumor.

A: The lesion from case 3 (Figure 1E and F) was treated with endoscopic full-thickness dissection. Preprocedural positron emission tomography/computed tomography ruled out metastasis, and endoscopic ultrasound confirmed the involvement of the muscularis propria (MP). The lesion showed poor lifting with submucosal injection, indicating involvement of MP; B and C: After circumferential incision, traction was applied with clips and a loop; D: During dissection, the circular muscle was attempted for removing. However, extensive fibrosis made it impossible to preserve the outer longitudinal muscle, likely due to tumor invasion into MP; E and F: The entire rectal muscular wall was removed; G: Clips with a detachable snare were used to close the defect; H: Histological analysis revealed a complete structure of MP and a negative vertical margin, classified as pT2Nx. The patient opted to follow-up instead of additional radical surgery.

Figure 4 Endoscopic salvage resection in a scar after endoscopic resection of rectal neuroendocrine tumor.

A and B: Previous polypectomy showed a positive margin on histology. The scar exhibited poor lifting with submucosal injection; C and D: After circumferential incision, traction was applied with clips and a loop; E and F: During dissection at the scar site, the circular muscle layer was carefully removed to perform intramuscular dissection. Histological analysis showed no residue tumor.

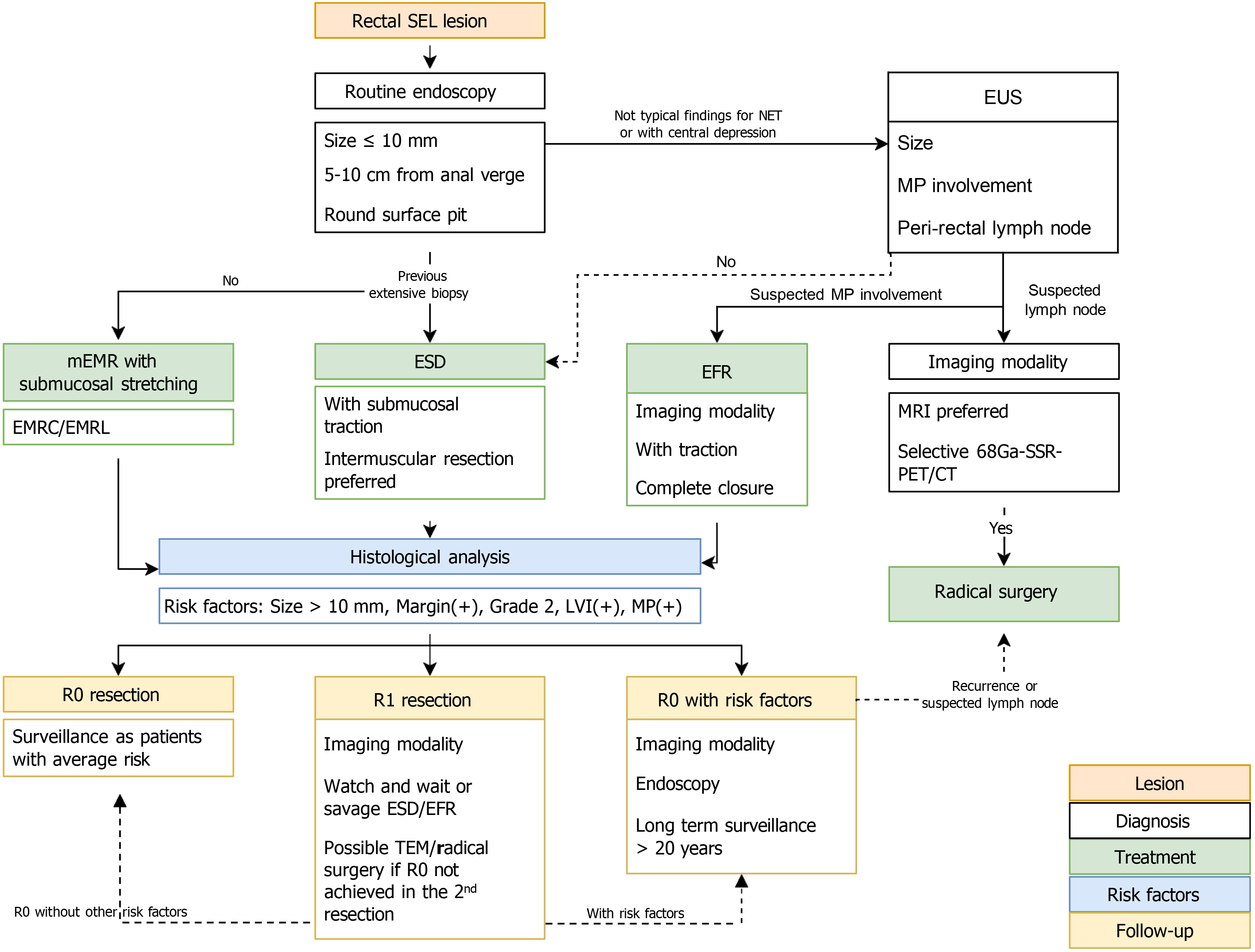

Figure 5 Proposed algorithm for the management of rectal neuroendocrine tumors.

SEL: Subepithelial lesion; NET: Neuroendocrine tumor; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; MP: Muscularis propria; mEMR: Modified endoscopic submucosal resection; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; EFR: Endoscopic full-thickness resection; EMRC: Cap-assisted endoscopic submucosal resection; EMRL: Endoscopic submucosal resection with a ligation device; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; 68Ga-SSR-PET/CT: Gallium-68-somatostatin receptor-positron emission tomography/computed tomography; R0 resection: Complete resection; R1 resection: Incomplete resection; TEM: Transanal endoscopic microsurgery.

- Citation: Liu JN, Chen H, Fang N. Current status of endoscopic resection for small rectal neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(19): 106814

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i19/106814.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i19.106814