Copyright

©2012 Baishideng Publishing Group Co.

World J Gastroenterol. Jul 7, 2012; 18(25): 3322-3326

Published online Jul 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i25.3322

Published online Jul 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i25.3322

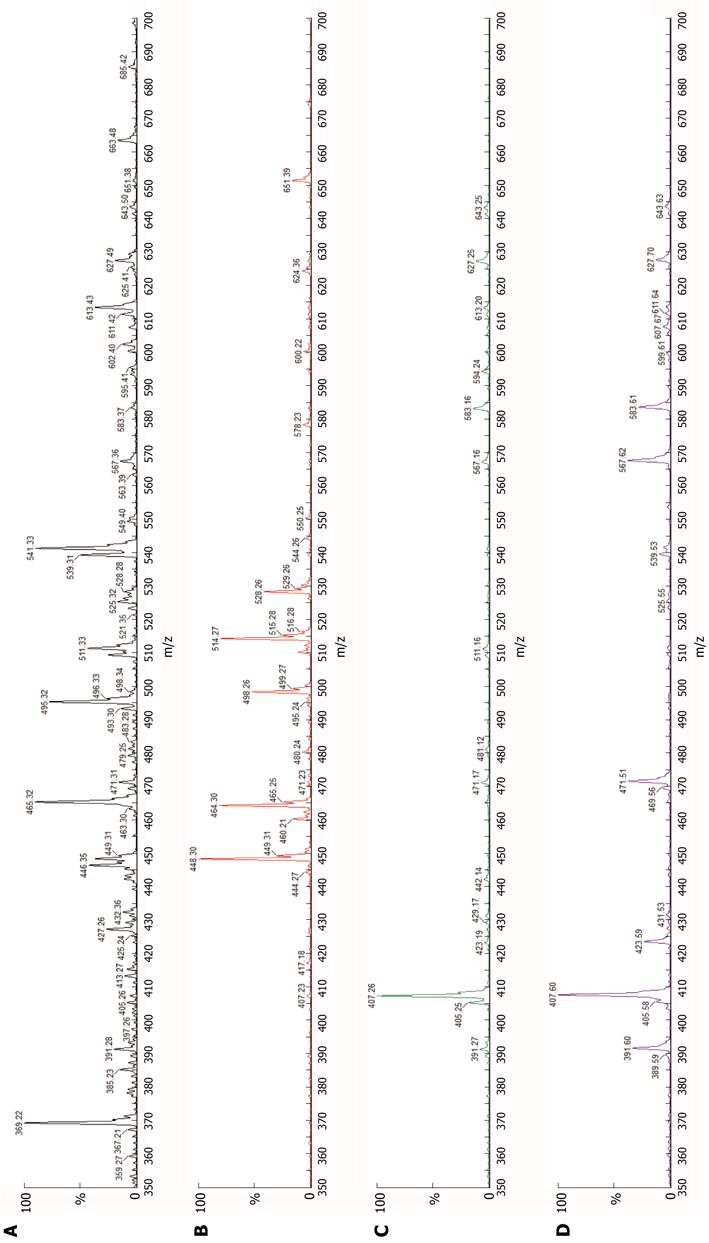

Figure 1 Bile acid mass spectra, urine.

A: Normal (neither icterus nor known amidation defect); B: Deficiency of bile salt export pump (BSEP) (intrahepatic cholestasis with icterus); C: Deficiency of cholate-CoA ligase (described elsewhere[3]); D: Deficiency of bile acid-CoA: amino acid N-acyltransferase (patient). Abscissa, mass-charge ratio (m/z); ordinate, intensity of ion current as percentage of intensity of most abundant peak in spectrum (%). From left to right, principal peak sites and the species represented are: 391: Unamidated chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA); 407: Unamidated cholic acid (CA); 448: Glycine-conjugated CDCA; 464: Glycine-conjugated CA; 471: Unamidated CDCA sulphate; 487: Unamidated CA sulphate; 498: Taurine-conjugated CDCA; 514: Taurine-conjugated CA; 528: Glycine-conjugated CDCA sulphate; 567: Unamidated CDCA glucuronide; 583: Unamidated CA glucuronide; 613: 27-Nor-cholestane pentol glucuronide; 627: Cholestane pentol glucuronide; 643: Cholestane hexol glucuronide. In normal urine (A), bile-acid and bile-alcohol peaks are just detectable. In urine from a patient with BSEP deficiency (B), increased excretion of glycine- and taurine-conjugated bile acids is apparent. Large quantities of non-conjugated species are present in both cholate-CoA ligase deficiency (C) and BAAT deficiency (D); differences between the two in size and distribution of this and other peaks are not apparent.

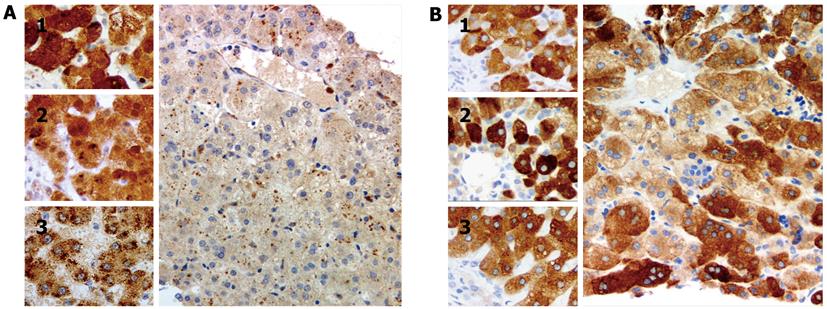

Figure 2 Photomicrographs of liver immunostained for enzymes that subserve bile-acid amidation.

A: Main image: Core needle biopsy specimen, patient liver (age 57 d); inset, control livers (1, infant, matched for age with patient, with cholestasis and extrahepatic biliary atresia; 2, infant, matched for age with patient, with intrahepatic cholestasis in setting of absence of bile salt export pump (BSEP) expression; and 3, adult without cholestasis). The patient liver lacks immunohistochemically demonstrable bile acid-CoA: amino acid N-acyltransferase (BAAT). Granular cytoplasmic marking, suggestive of peroxisomal location, is found in (3); marking is more diffuse in the livers of age-matched infants; B: Tissue specimens as in (A). Diffuse cytoplasmic marking for cholate-CoA ligase (CCL) is seen in patient liver (main image) and in control livers (1, infant, matched for age with patient, with cholestasis and extrahepatic biliary atresia; 2, infant, matched for age with patient, with intrahepatic cholestasis in setting of absence of BSEP expression; and 3, adult without cholestasis). A, anti-BAAT antibody, and B, anti-CCL antibody (see principal text for sources); in all images, reaction development with EnVision proprietary technique (Dako UK, Ely, United Kingdom), haematoxylin counterstain, original magnification 200 ×.

- Citation: Hadžić N, Bull LN, Clayton PT, Knisely A. Diagnosis in bile acid-CoA: Amino acid N-acyltransferase deficiency. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(25): 3322-3326

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i25/3322.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i25.3322