Copyright

©2012 Baishideng Publishing Group Co.

World J Gastroenterol. Mar 21, 2012; 18(11): 1191-1201

Published online Mar 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i11.1191

Published online Mar 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i11.1191

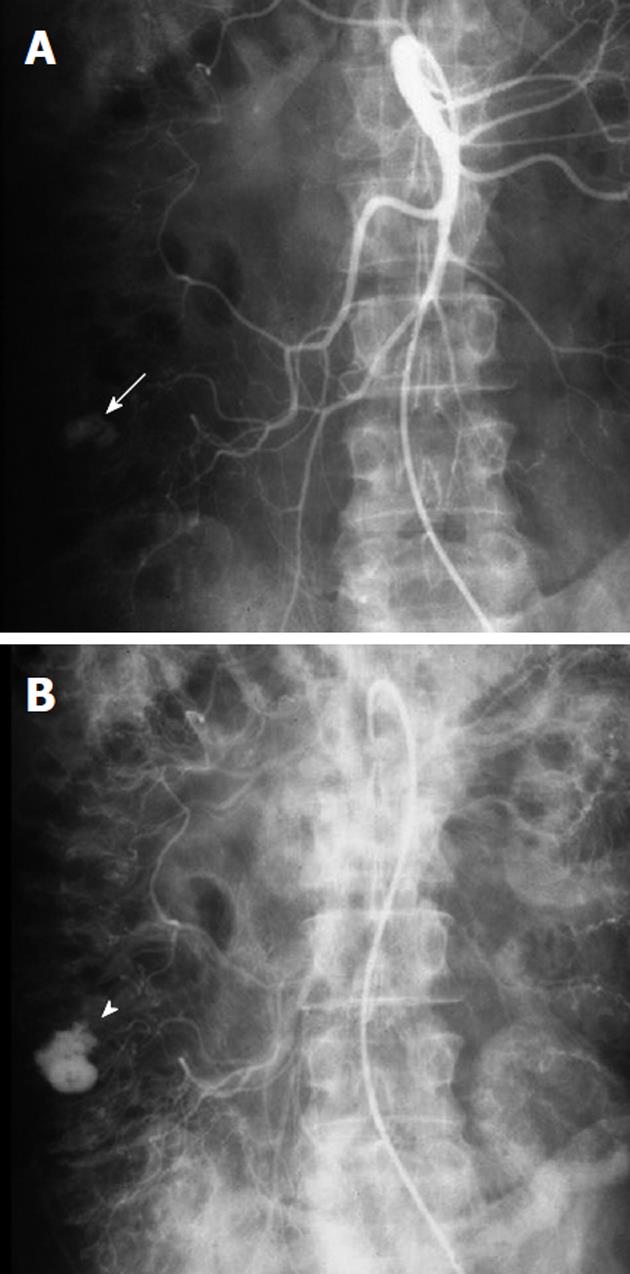

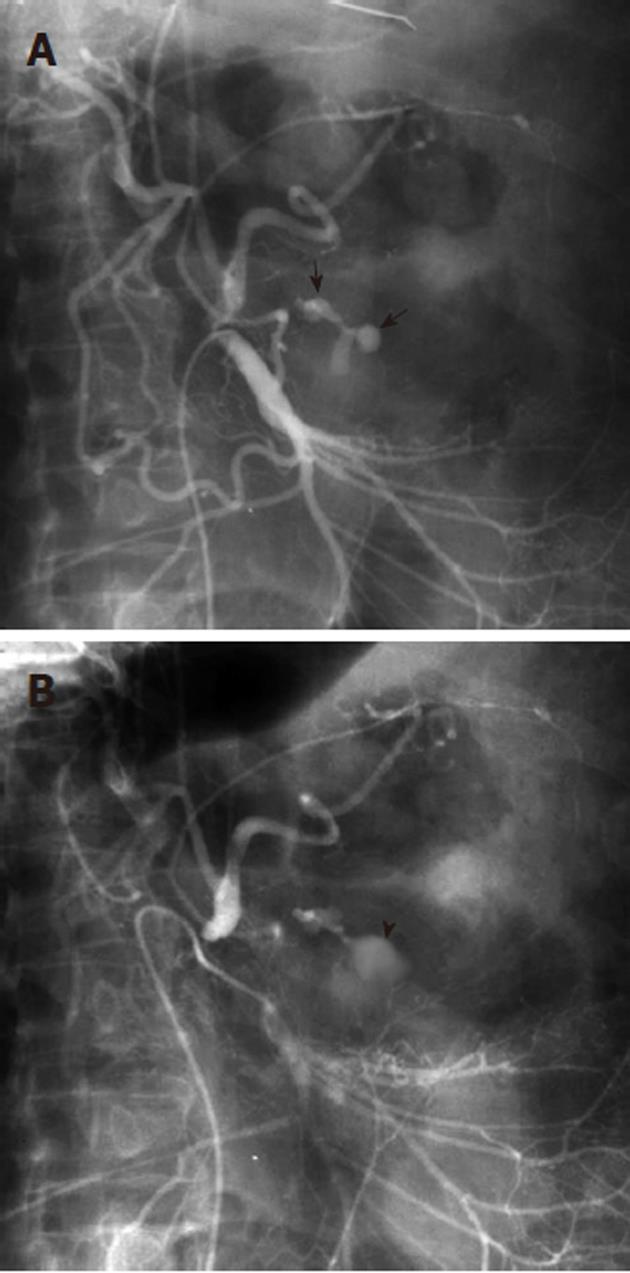

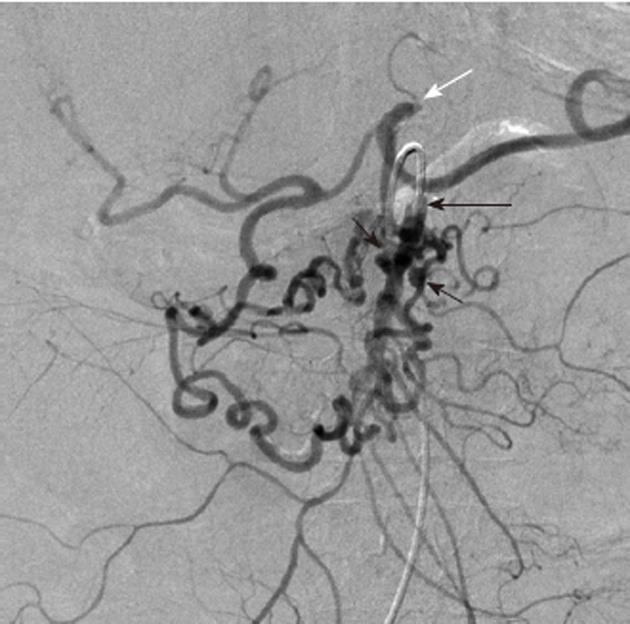

Figure 1 Example of a bleeding colonic diverticulum.

A: Arterial phase of a superior mesenteric artery arteriogram, obtained in a patient with acute lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and a prior history of diverticulitis shows a rounded contrast collection (white arrow) arising from a branch of the right colic artery; B: In the later arterial phase the collection (white arrowhead) has increased in size but maintains the rounded configuration. The extravasated contrast medium is pooling in a colonic diverticulum, indicating that diverticular hemorrhage is the etiology of the lower GI bleeding.

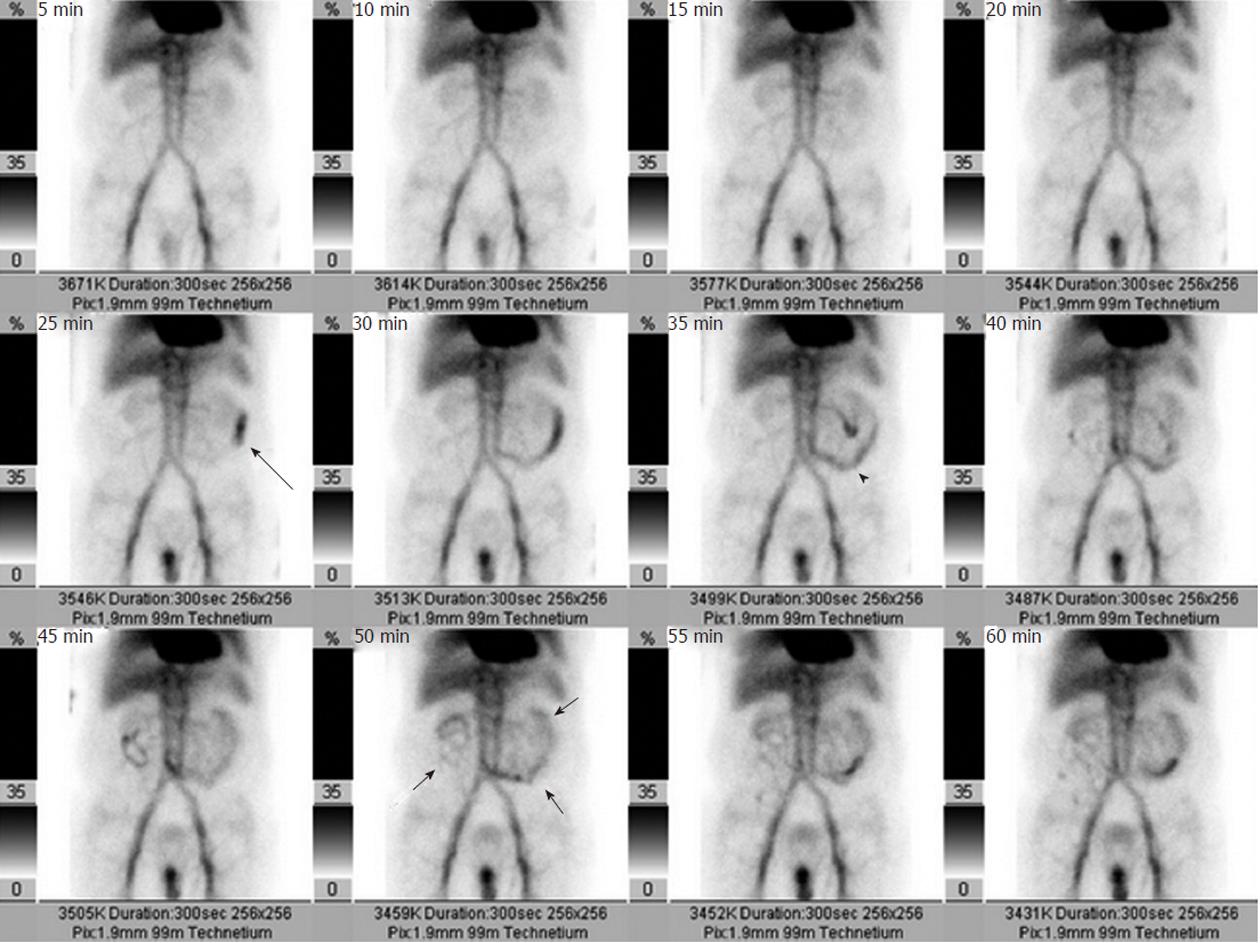

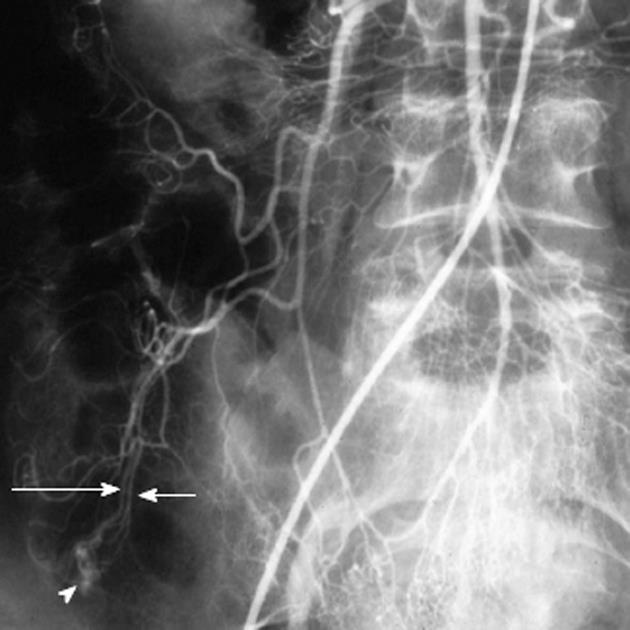

Figure 2 A radionuclide Tc99m-labeled red blood cell scan obtained in a patient with acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage shows radioisotope accumulation in the left abdomen at 25 min (black arrow), which by 35 min has a small bowel location (black arrowhead) and by 50 min has distributed throughout much of the small intestine (short black arrows).

The study demonstrates that the bleeding source is in the small bowel, and thus serves to appropriately direct either angiography or surgery.

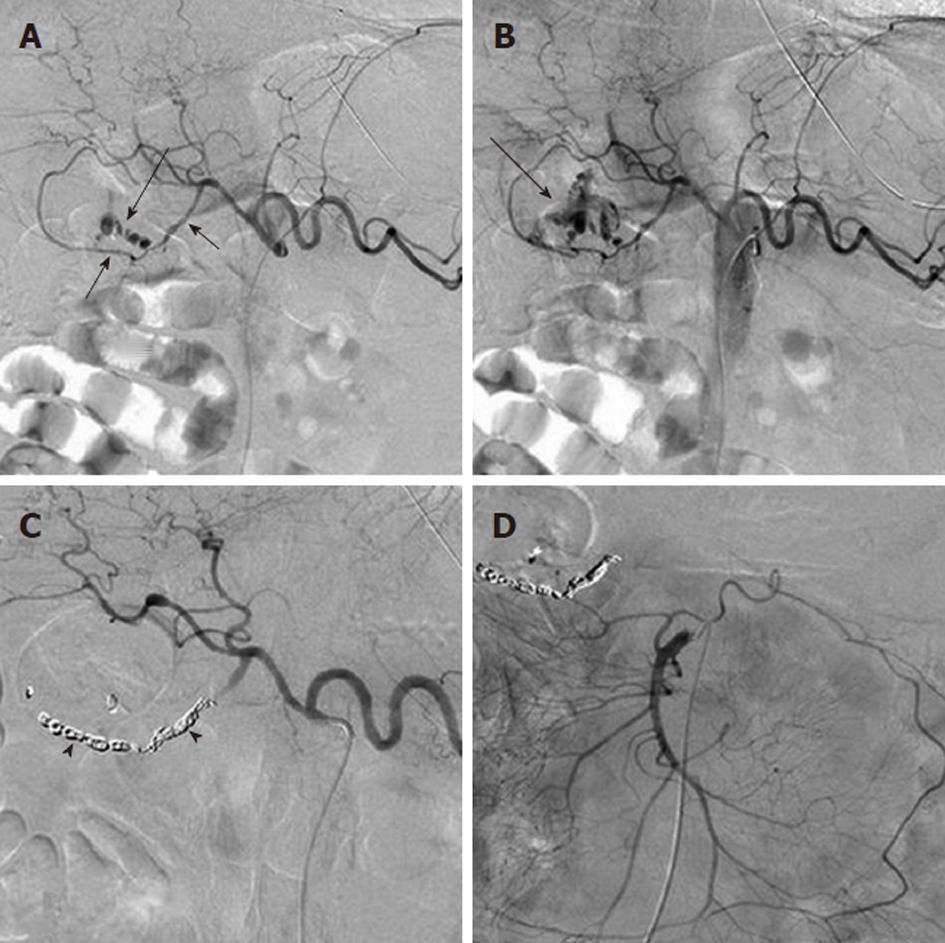

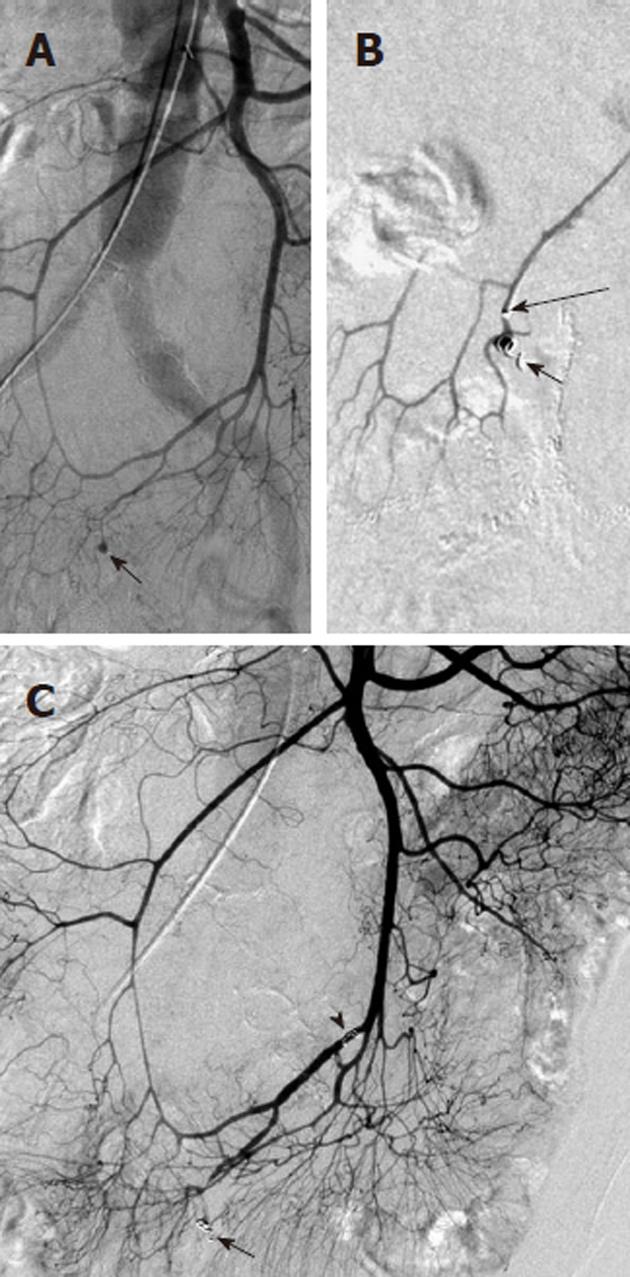

Figure 3 Angiographic diagnosis and transcatheter treatment of duodenal hemorrhage.

A: Celiac digital subtraction angiography (DSA) arteriogram obtained in a patient with copious bleeding seen endoscopically in the duodenum shows focal contrast extravasation (black arrow) arising from the gastroduodenal artery (GDA); B: An image slightly later in the arterial phase of the DSA shows increasing extravasation (black arrow); C: The GDA was successfully coil embolized using microcoils (black arrowheads) through a microcatheter; D: An superior mesenteric artery DSA arteriogram was performed after the coil embolization in order to exclude any additional contribution to the duodenal hemorrhage from the pancreaticoduodenal arcade, as the duodenum has a rich collateral blood supply.

Figure 4 Inferior mesenteric artery digital subtraction angiography arteriogram shows the marginal artery of Drummond (black arrowheads), which courses along the mesenteric border of the colon.

There is retrograde filling of the left branch of the middle colic artery (black arrow), which arises from the dorsal pancreatic artery (white arrow) as an anatomic variant. There is also filling of pancreatic branches (long white arrows) along with partial opacification of the splenic and hepatic arteries.

Figure 5 Contrast extravasation demonstrating location of lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

A: Superior mesenteric artery arteriogram shows an amorphous contrast collection (black arrow) arising from the left branch (long black arrow) of the middle colic artery; B: Later in the arterial phase the collection has increased and is layering dependently in the colon, assuming the configuration of the haustra. This extravasated contrast medium denotes the site of lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Figure 6 The pseudovein sign in gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

A: Superior mesenteric artery arteriogram shows a branching contrast collection (black arrows), overlying the gastric air shadow. The collection has the appearance of a vascular structure such as a vein; B: A later image in the arterial injection shows that the collection (black arrowhead) has a more amorphous appearance, and represents extravasation. The former appearance is an example of the “pseudovein sign”.

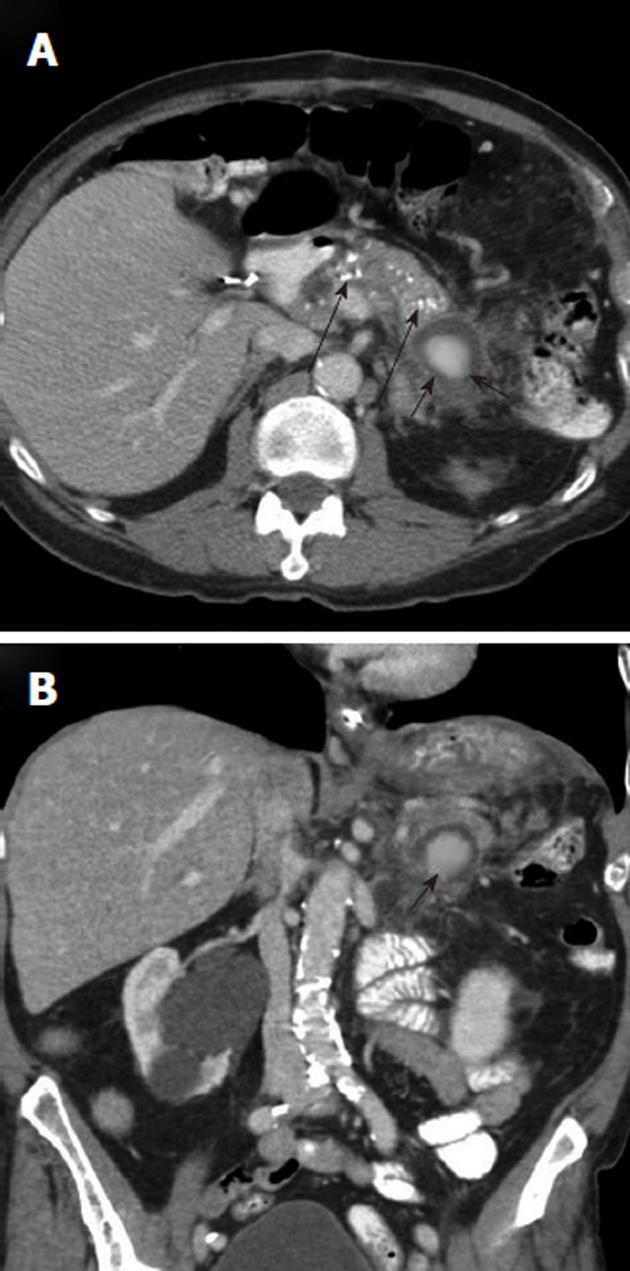

Figure 7 Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage from pancreatitis related pseudoaneurysm.

A: Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan, obtained in a patient who presented with hematemesis, shows pancreatic calcifications (long black arrows) indicating chronic pancreatitis and an enhancing mass (black arrows) in the pancreatic tail; B: Coronal CECT shows the rounded enhancing mass (black arrow) with surrounding inflammatory changes. This is suspicious for a pancreatitis-related pseudoaneurysm as the source of the upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Figure 8 Transcatheter treatment of a pancreatitis related pseudoaneurysm.

A: Selective splenic artery digital subtraction angiography arteriogram shows that the pseudoaneurysm (white arrow) arises directly from the splenic artery; B: Coil embolization of the pseudoaneurysm (black arrow) and of the splenic artery (black arrowheads) both proximal and distal to the pseudoaneurysm was successful in controlling the hemorrhage. Arterial pseudoaneurysms associated with pancreatitis have a significant risk of rupture; if this occurs there is an extremely high mortality rate.

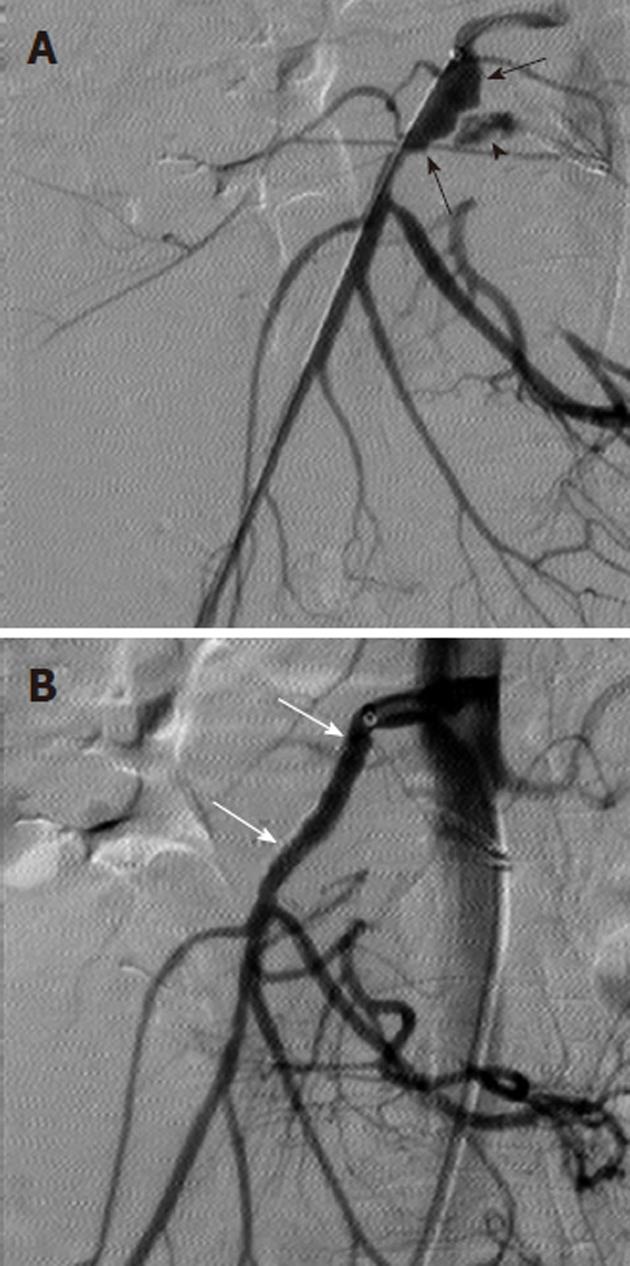

Figure 9 Treatment of ruptured pseudoaneurysm with covered intravascular stent.

A: Digital subtraction angiography arteriogram obtained in a patient with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and a history of pancreatitis shows irregular dilatation of the proximal superior mesenteric artery (black arrows) and contrast extravasation (black arrowhead) consistent with pseudoaneurysm rupture; B: The hemorrhage was successfully controlled with covered stent (white arrows) placement.

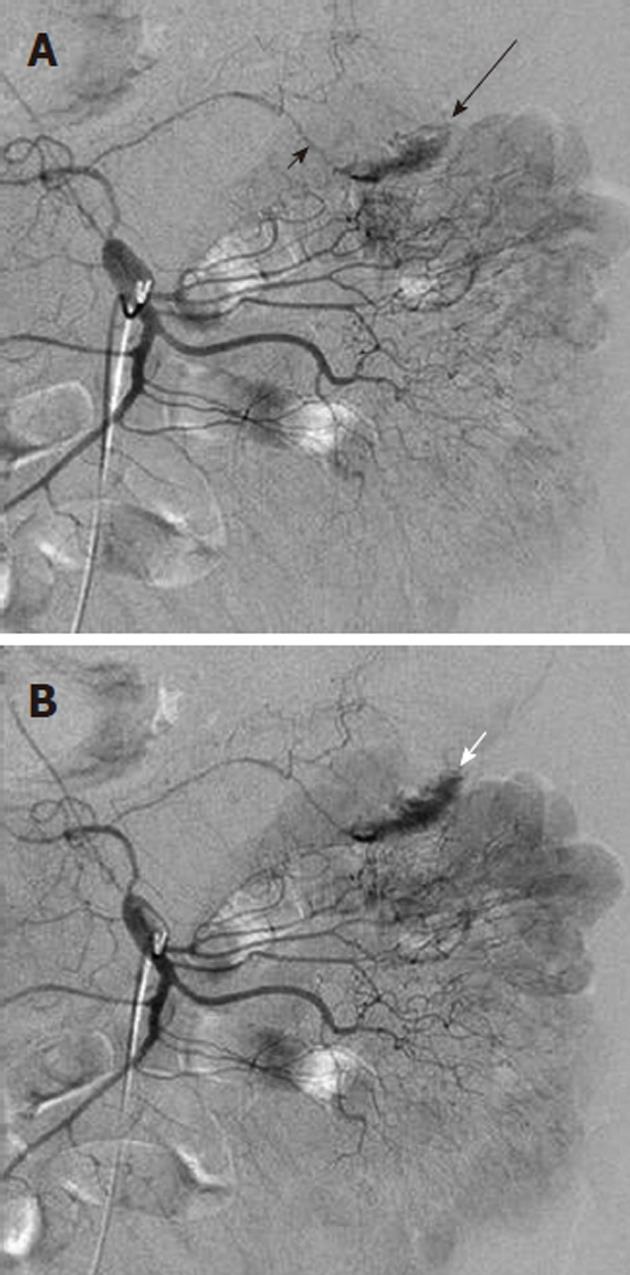

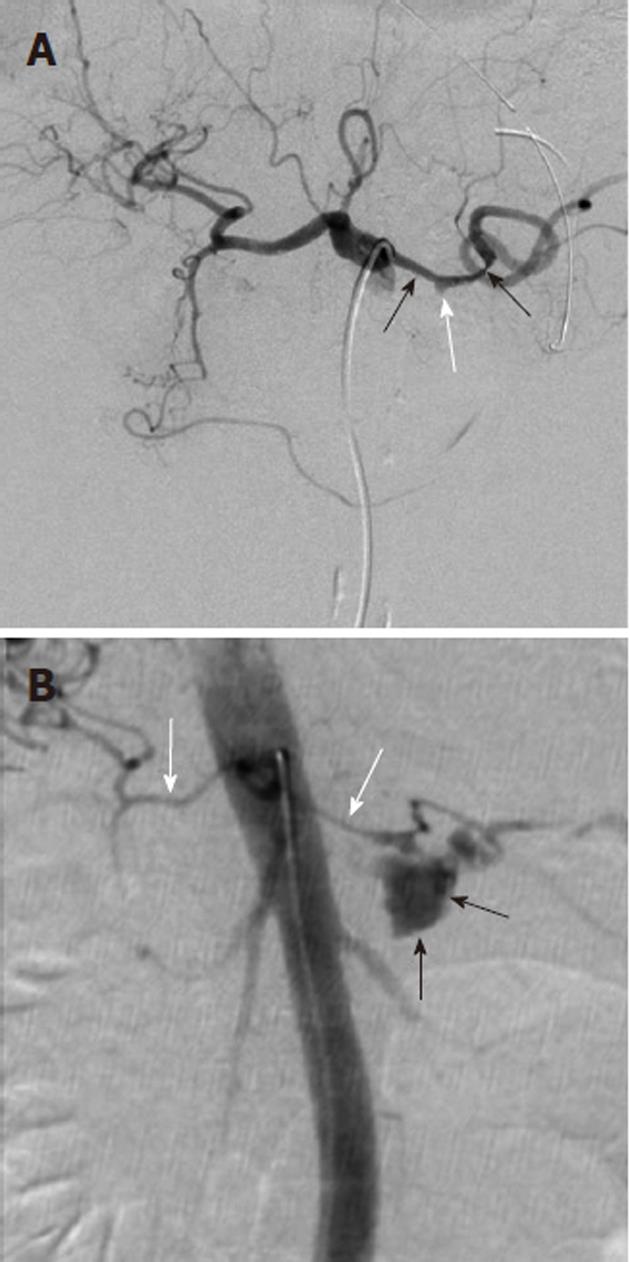

Figure 10 Life-threatening hemorrhage from pancreatitis related pseudoaneurysm.

A: Celiac digital subtraction angiography arteriogram obtained in a patient with intermittent upper gastrointestinal bleeding and a history of chronic pancreatitis shows an irregular caliber to the splenic artery (black arrows) and a small pseudoaneurysm (white arrow). No intervention was performed at the time of this examination; B: Two weeks after the celiac arteriogram the patient presented with acute onset of severe abdominal pain and profound hypotension. Repeat angiography showed brisk contrast extravasation (black arrows) from the splenic artery. Note the marked vasoconstriction (white arrows) of the hepatic and splenic arteries due to the life-threatening hemorrhage.

Figure 11 Digital subtraction angiography obtained with the catheter tip (long black arrow) in the superior mesenteric artery shows tortuous and dilated inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries with at least two small pseudoaneurysms (black arrows).

There is retrograde filling of the celiac arterial branches via the inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries arcade, because the celiac origin is occluded (white arrow). The pseudoaneurysms are at risk of rupture.

Figure 12 Magnified view from a superior mesenteric artery arteriogram shows an area of abnormal vascularity (white arrowhead) in the cecal area, with an early draining vein (long white arrow) paralleling the arterial inflow (white arrow).

This simultaneous filling of the feeding artery and draining vein is known as the “tram-track” sign and is characteristic of angiodysplasia.

Figure 13 Example of nontarget embolization during treatment of lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

A: Superior mesenteric artery arteriogram obtained in a patient with lower gastrointestinal bleeding shows a focal contrast collection (black arrow) arising from a branch of the ileocolic artery; B: A microcatheter was introduced and was subselectively positioned with the tip (long black arrow) immediately proximal to the focal extravasation and a microcoil (black arrow) was placed; C: While attempting to place a second microcoil, the microcatheter tip was displaced proximally resulting in coil placement in a nontarget location (black arrowhead). Repeat digital subtraction angiography shows that the second coil is nonocclusive and the initially placed coil has successfully controlled the bleeding source.

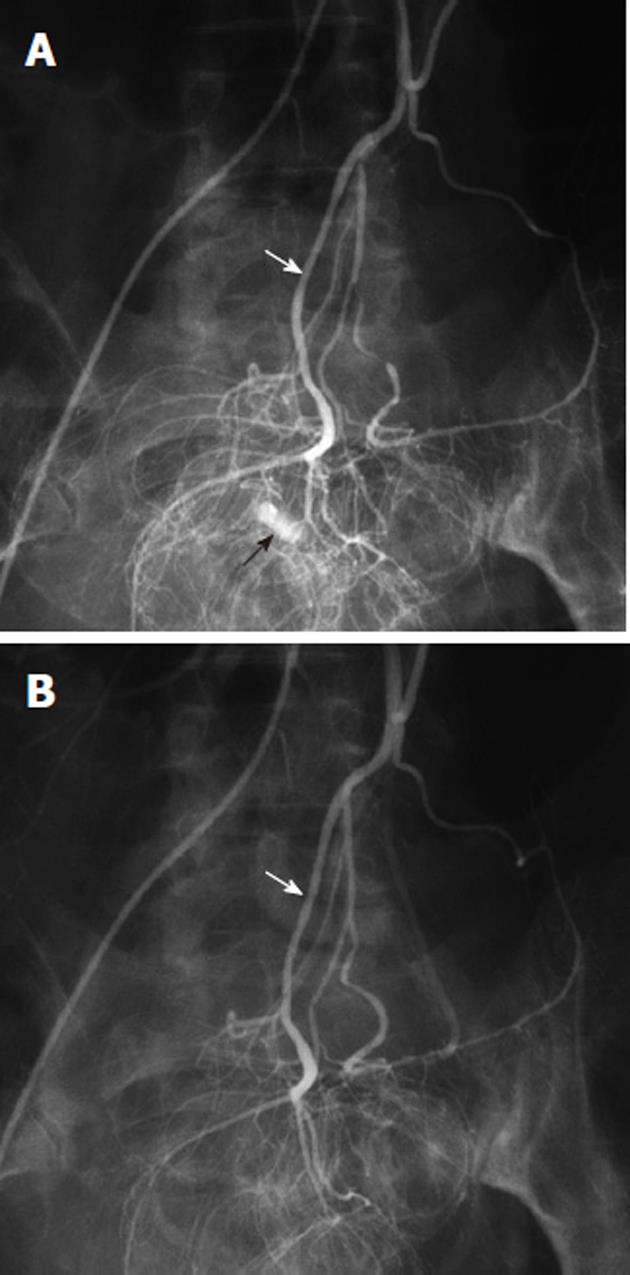

Figure 14 Vasopressin infusion therapy for lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

A: Inferior mesenteric digital subtraction angiography arteriogram shows contrast extravasation (black arrow) in the rectosigmoid colon, arising from a branch of the superior hemorrhoidal artery (white arrow); B: Following transcatheter arterial vasopressin infusion, there is no longer any evidence of active bleeding from the superior hemorrhoidal (white arrow) arterial distribution.

- Citation: Walker TG, Salazar GM, Waltman AC. Angiographic evaluation and management of acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(11): 1191-1201

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i11/1191.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i11.1191