Published online Nov 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i21.3407

Peer-review started: May 23, 2019

First decision: September 9, 2019

Revised: September 21, 2019

Accepted: October 5, 2019

Article in press: October 5, 2019

Published online: November 6, 2019

Mental health is one of the important dimensions of health, while depression is an important indicator of mental health evaluation.

To investigate the association between intergenerational emotional support and depression of non-cohabiting parents (≥ 45 years old) in China.

We used the fourth wave data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (2015). The data was made up of ten main modules, the associated two datasets, and five constructed datasets. The first step is to select the corresponding module data according to the purpose of this study. Moreover, the data of the six modules are integrated by the unique ID code and we choose depression and non-cohabiting items as the selection conditions. 4810 samples were selected, which mainly included data on intergenerational emotional support and the individual scores on depressive symptoms.

The average age of 4810 respondents was (60.56 ± 14.613) years old. Females were accounted for more than half of the samples (52.6%). 74.0% respondents from rural areas and approximately 63.3% of the participants had a chronic disease. The mean value of the CESD-10 score was 13.06 (SD5.225). Both faces to face and phone contacts were protective factors on depression symptoms in the mid-aged and seniors in China (P < 0.05). In terms of the frequency of face to face contact, the more frequently you met your parents, the lower your parents' depressive score was. Also, phone contact variable results are displayed as a positive correlation completely between inter-generational contacts from children and depressive symptoms in non-cohabiting parents in China. Children’s education level and income level were also reducing the risk of depression in non-cohabiting parents. However, gender, children’s numerous, chronic disease and chronic disease number were the risk factors.

Intergenerational emotional support is associated with depressive symptoms in non-cohabiting parents in China. However, the relationship was also affected by other variables.

Core tip: The increasing prevalence of depression among the mid-elderly is an emerging major public health problem in China. Intergenerational emotional support is associated with depressive symptoms in non-cohabiting parents in China. And to provide an intuitive and realizable intervention point for public campaigns or family education programs for community mental health services.

- Citation: Jia YH, Ye ZH. Impress of intergenerational emotional support on the depression in non-cohabiting parents. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(21): 3407-3418

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i21/3407.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i21.3407

Mental health is one of the important dimensions of health, while depression is an important indicator of mental health evaluation[1]. Globally, it is estimated that 4.4% of the world’s population suffering from depression, with a total number of more than 300 million (World Health Organization, 2017).The increasing prevalence of depression among the mid-elderly is an emerging major public health problem in China, the prevalence of geriatric depression around 17%, and as high as 39.86%[2,3].

Syntheses of the available epidemiological literature indicated that depression could decrease physical function, daily life ability, cognitive decline, and so on[4]. Many studies have already shown that depression was associated with many factors, such as gender[5], alcohol[6], economic status[7] and social capital[8]. Among the many causes of depression, social capital may be particularly important[9,10]. A recent literature reported that emotional support was more closely related to depression than instrumental support, especially in adults aged 18 to 50[11]. At current China, population aging and massive rural-to-urban migration not only changed the family system but also changed the contact mode between parents and their non-cohabiting adult children. In addition, face to face contact is more difficult to achieve for elderly parents whose adult children live far away from them. However, there are few studies on this topic and the results are inconsistent.

The objective of our study was to assess the association between the frequency of contact and the risk of depression between elderly parents and non-cohabitating adult children. We hypothesized that not regularly associating with non-cohabitating adult children increases the risk of subsequent depression of mid-aged and elderly parents. In other words, both face-to-face and telephone contact have positive effects on depression in the elderly. Meanwhile, we also used a comparative method to identify whether there was a difference in effectiveness between phone contact and face-to-face contact. Based on the above, we expected to provide an intuitive and achievable intervention point for public activities or family education projects for Community Mental Health Service.

China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) presided over by the Peking University, is a nationally representative longitudinal study of Chinese community-dwelling residents aged 45 and older and their spouses. It was designed based on the Health and Retirement Study in the United States, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, and similar longitudinal aging surveys in other countries[12,13].

The data we used come from the fourth wave of CHARLS, which was held in 2015 publicly released on May 31, 2017, covered 21789 people (689 died) in 12236 households in 451 villages/communities. The data was made up of ten main modules, the associated two datasets (sample information and cross-sectional weights), and five constructed datasets. In our study, the data selection process is as follows: The first step is to select the corresponding module data according to the purpose of this study. Six module data (Demographic background/Family information/Family transfer/Health status and functioning/Housing Characteristics/Individual income) enter the preliminary selection. Then, the data of the 6 modules are integrated by the unique ID code to obtain 21095 samples. Thirdly, 20967 samples were obtained with depression items as the selection conditions. Fourthly, filter with face to face item to get 12131 cases. Lastly, the final sample of 4810 people were obtained by deleting the sample of living with children.

Depression: In our study, Depression variable was measured by the Chinese version 10-item short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CESD-10). The 10 items consist of eight negative-oriented questions and two positive-oriented issues. Negative aspects include “I was bothered by things that don’t usually bother me” and positive ones are “I felt hopeful about the future” and “I was happy”. Each item was scored on a four-point scale, 0 = rarely or none of the time (< 1 d), 1 = some or a little of the time (1-2 d), 2 = occasionally or a moderate amount of the time (3-4 d), and 3 = most or all of the time (5-7 d). The two positive items were scored inversely. The CESD-10 score ranged from 0 to 30, the severity of depressive symptoms with scores. The scale represents a good reliability and validity of participants (Cronbach’s α = 0.81)[14,15].

Frequency of contact: Trained interviewers utilized verbal questions to assess contact frequency with non-cohabitating adult children, which was our primary exposure of interest. Participants were asked, “How often do you see (child’s name)?” The problem will be abbreviated “face to face” in the text and “How often do you contact with (child’s name) either by phone, text message, mail, or email, when you didn’t live with (child’s name)?” Will be abbreviated “phone contact”. Ten response options were available for the two questions, ranging from 1 = “almost every day”, 2 = “2-3 times a week”, 3 = “once a week”, 4 = “every two week”, 5 = “once a month”, 6 = “once every three months”, 7 = “once every six months”, 8 = “once a year”, 9 = “almost never” to 10 = “other”. Up till now there was no specific study to indicate the best critical point for effectiveness of social contact, however, previous studies have shown that face-to-face or phone contact once a month or once a week has protective effects on depression in elderly[16]. On account of the previous researches, we divided the respondents into four groups according to the frequency of their “phone” and “face-to-face” contact. The first group was consisted of participants who responded that they had frequent phone contact (ranging from 1-3) and frequent face-to-face contact (ranging from 1-4). The second group 2 was comprised of participants who responded that they had infrequent (ranging from4 to 9) phone contact and frequent face-to-face contact. The third group was comprised of participants who responded that they had frequent phone contact and infrequent face-to-face contact (ranging 5-9). The fourth group was comprised of participants who responded as having infrequent phone contact and infrequent face-to-face contact[17].

Other variables: Other variables that may affect contact frequency and depressive symptoms were also included in the analysis. These variables were divided into three categories: demographic characteristics, socio-economic characteristics, and current health conditions.

For the descriptive statistics, we used independent-sample t-test and ANOVA to compare the variables. After testing collinearity, stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis was used to explore the correlation between various factors and depression risk of non -cohabiting parents. Statistical significance is expressed as lP < 0.05, mP < 0.01, nP < 0.001. Data were analyzed using SPSS19.0.

The general characteristics and each groups’ contact frequency of the total participants are provided in Table 1. In the all participants, the mean value of CESD-10 score is 13.06 (SD5.225). The proportion of mid-aged and elderly persons in China could meet their children at least once a month is 65.5%, and 50.4% could communicate with their children at least once a week by phone, text message, mail or email. In terms of demographic factors, the average age was (60.47 ± 15.012) years old; females accounted for more than half of the samples (51.9%). The mean number of adult children was 2.77 (SD = 1.316). The specific classification information is as follows: 17.5% had one child, 32.2% had two, 21.3% had three, 13.4% had four, and 15.6% had five children or above. On the gender of family children, only 22.6 % of households have girls, 15.6% have boys, and more than 61.1 % have both. Among socio-economic and health factors, almost 100% had some formal education. Among them, 15.7% had attained primary school (1-6 years), junior to senior school (7-12 years) education accounted for 52.2%, and 32.0% had attained university education (over 13 years). In term of income, half (50.1%) of the children earn between 10001 and 50000 Yuan a year. Respondents from rural areas (74.0%) were more than twice of those from urban areas (25.4%). Approximately 63.3% of the participants had chronic disease, the mean number of diseases was 1.97 (SD = 0.846), and 62.5% of the respondents suffer from more than two chronic diseases.

| Variables | mean/n (%) | SD | |

| Dependent variable | Depressive symptoms (CESD-101 score) (0-30) | 13.06 | 5.225 |

| Independent variable | Face to face | 3.94 | 2.546 |

| Almost every day | 1224 (25.4) | ||

| 2-3 times a week | 448 (9.3) | ||

| Once a week | 532 (10.9) | ||

| Every two weeks | 434 (9) | ||

| Once a month | 526 (10.9) | ||

| Once every three months | 494 (10.3) | ||

| Once every six months | 502 (10.4) | ||

| Once a year | 516 (10.7) | ||

| Almost never | 33 (0.7) | ||

| Missing | 110 (2.3) | ||

| Phone contact | 2.95 | 2.302 | |

| Almost every day | 531 (11) | ||

| 2-3 times a week | 809 (16.8) | ||

| Once a week | 1086 (22.6) | ||

| Every two weeks | 655 (13.6) | ||

| Once a month | 471 (9.8) | ||

| Once every three months | 108 (2.2) | ||

| Once every six months | 47 (1) | ||

| Once a year | 15 (0.3) | ||

| Almost never | 301 (6.3) | ||

| Missing | 787 (16.4) | ||

| Demographic factors | Age | 60.47 | 15.012 |

| 45-50 (ref.) | 583 (12.1) | ||

| 51-60 | 1479 (30.7) | ||

| 61-70 | 1543 (32.1) | ||

| 71- | 1011 (21) | ||

| Missing | 194 (4) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male (ref.) | 2310 (48) | ||

| Female | 2494 (51.9) | ||

| Missing | 6 (0.1) | ||

| Children’s number | 2.77 | 1.316 | |

| 1 child | 842 (17.5) | ||

| 2 children | 1548 (32.2) | ||

| 3 children | 1024 (21.3) | ||

| 4 children | 644 (13.4) | ||

| 5 and above | 752 (15.6) | ||

| Gender of family children2 | |||

| Male | 1086 (22.6) | ||

| Female | 748 (15.6) | ||

| Both | 2940 (61.1) | ||

| Missing | 36 (0.7) | ||

| Socio-economic factors | Education level3 (children) | ||

| Illiterate | 1 (0.0) | ||

| 1-6 years education | 756 (15.7) | ||

| 7-12 years education | 2509 (52.2) | ||

| 13 years education and above | 1538 (32.0) | ||

| Missing | 6 (0.1) | ||

| Income (children)4 | 2.96 | 1.215 | |

| No income | 946 (19.7) | ||

| 1-10000 yuan | 271 (5.6) | ||

| 10001-50000 yuan | 2139 (44.5) | ||

| 50001-100000 yuan | 920 (19.1) | ||

| More than 100000 yuan | 534 (11.1) | ||

| Areas of China | |||

| Urban | 1224 (25.4) | ||

| Rural (ref.) | 3559 (74.0) | ||

| Missing | 27 (0.6) | ||

| Current health conditions | Chronic disease | ||

| No | 1767 (36.7) | ||

| Yes | 3043 (63.3) | ||

| Chronic diseases number5 | 1.97 | 0.846 | |

| 1 | 1143 (37.6) | ||

| 2 | 860 (28.3) | ||

| 3 and above | 1040 (34.2) |

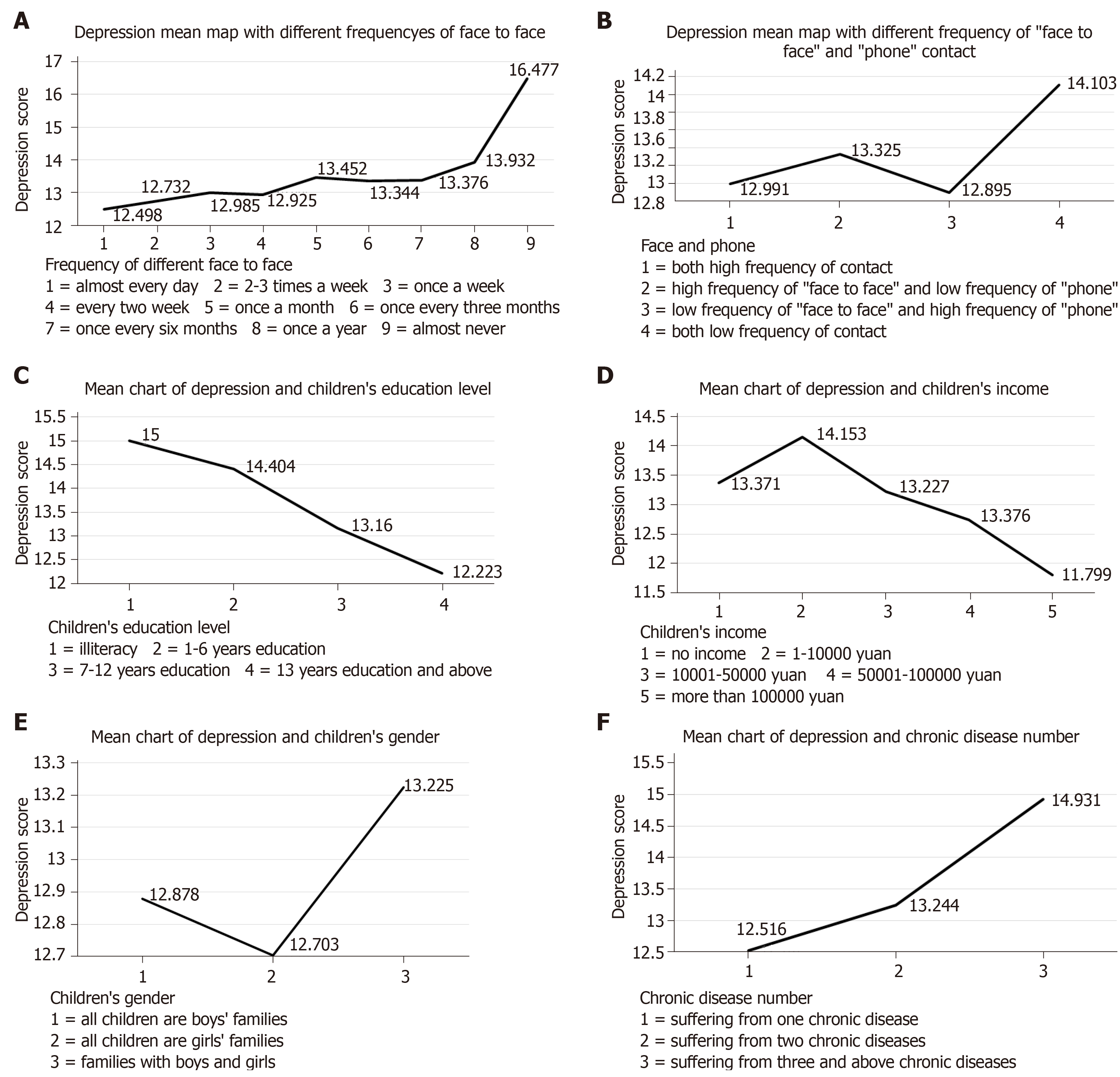

Results of the independent variable are shown in Table 2. The results indicated that there was a significantly positive correlation between depressive symptoms in non-cohabiting parents and intergenerational contacts from children in China (P < 0.05). In terms of the frequency of face to face contact, the more frequently you met your parents, the lower your parents’ depressive score was. Our study suggested that the optimal face to face communication to parent(s) for 2-3 times a week could lower depression obviously (12.50 ± 5.478). Phone contact variable results are displayed a positive correlation completely between inter-generational contacts from children and depressive symptoms in non-cohabiting parents in China. With the decrease of telephone contact frequency, the depression score increased significantly. As for the interaction of face-to-face and telephone contacts, there was no statistical difference between group 1 and group 3, both of which were better than those of the other two groups (group 2 and group 4), and group 4 was the highest score on depression, As shown in Figure 1A and B.

| Variables | Depressive symptoms (cesd-10 score) (0-30)1 | F | P value2 | |

| Dependent variable | Depressive symptoms | 13.06 ± 5.225 | ||

| Independent variable | Face to face | 6.622 | 0.000a | |

| almost every day | 12.50 ± 5.478 | |||

| 2-3 times a week | 12.73 ± 5.158 | |||

| once a week | 12.99 ± 4.764 | |||

| every two weeks | 12.92 ± 5.290 | |||

| once a month | 13.45 ± 5.107 | |||

| once every three months | 13.34 ± 5.043 | |||

| once every six months | 13.38 ± 4.895 | |||

| once a year | 13.93 ± 5.353 | |||

| almost never | 16.48 ± 6.723 | |||

| Phone contact | 5.334 | 0.000a | ||

| almost every day | 12.97 ± 4.804 | |||

| 2-3 times a week | 12.90 ± 4.872 | |||

| once a week | 13.14 ± 4.915 | |||

| every two weeks | 13.83 ± 5.261 | |||

| once a month | 14.13 ± 5.492 | |||

| once every three months | 14.13 ± 6.148 | |||

| once every six months | 13.91 ± 5.790 | |||

| once a year | 12.70 ± 4.773 | |||

| almost never | 12.20 ± 6.815 | |||

| frequency of contact3 | 5.717 | 0.001a | ||

| Group 1: (both) (ref) | 12.99 ± 5.071 | |||

| Group 2: (face to face) | 13.33 ± 4.958 | |||

| Group 3: (phone) | 12.90 ± 6.103 | |||

| Group 4: (neither) | 14.28 ± 5.987 |

In the bivariate analysis, gender and chronic diseases were associated with the non-cohabiting parents in depression, this result can be seen from Table 3. Women have a higher depression score than men, and people with chronic diseases are more prone to depression than normal ones. There was no significantly difference in residence areas. In the study, the results exhibiting of non-cohabiting parents in depression were acceptable.

| Variables | Depressive symptoms (cesd-10 score) (0-30)1 | F or t | P value6 | |

| Demographic factors | Age | 0.600 | 0.615 | |

| 45-50 (ref.) | 12.81 ± 5.070 | |||

| 51-60 | 13.14 ± 5.141 | |||

| 61-70 | 13.02 ± 5.290 | |||

| 71- | 13.09 ± 5.245 | |||

| Gender | 4.641 | 0.03a | ||

| Male (ref.) | 12.85 ± 5.123 | |||

| Female | 13.24 ± 5.314 | |||

| Children’s number | 7.775 | 0.000b | ||

| 1 child | 12.20 ± 4.628 | |||

| 2 children | 13.22 ± 4.903 | |||

| 3 children | 13.46 ± 5.354 | |||

| 4 children | 13.20 ± 5.037 | |||

| 5 and above | 13.00 ± 6.279 | |||

| Gender of family children2 | 3.881 | 0.021a | ||

| Male | 12.88 ± 4.863 | |||

| Female | 12.70 ± 4.936 | |||

| Both | 13.22 ± 5.403 | |||

| Socio- economic factors | Education level3 (children) | 30.738 | 0.000b | |

| illiterate | 15.00 | |||

| 1-6 years education | 14.40 ± 5.669 | |||

| 7-12 years education | 13.16 ± 5.264 | |||

| 13 years education and above | 12.22 ± 4.76 | |||

| income (children)4 | 13.112 | 0.000b | ||

| No income | 13.37 ± 5.481 | |||

| 1-10000 yuan | 14.15 ± 5.754 | |||

| 10001-50000 yuan | 13.23 ± 5.384 | |||

| 50001-100000 yuan | 12.74 ± 4.781 | |||

| More than 100000 yuan | 11.80 ± 4.238 | |||

| areas of China | 0.678 | 0.498 | ||

| Urban | 13.14 ± 5.181 | |||

| Rural (ref.) | 13.03 ± 5.248 | |||

| Current health conditions | Chronic disease | -8.627 | 0.000b | |

| No | 12.21 ± 4.734 | |||

| Yes | 13.55 ± 5.431 | |||

| Chronic diseases num5 | 57.750 | 0.000b | ||

| 1 | 12.52 ± 5.049 | |||

| 2 | 13.24 ± 5.004 | |||

| 3 and above | 14.93 ± 5.871 |

In the multivariable (Table 3) analysis, education level (children), income (children), children’s numerous, chronic diseases’ number, together with gender of family children were statistically significant on depression. Table 3 also indicated that education level (children), income (children) were the protective factors of depressive symptoms. However, children’s number and chronic diseases’ number were the risk factors. In terms of age, there's no obviously statistical difference with the depression of the non-cohabiting parents in China.

In all, there was a significantly positive correlation between depressive symptoms in the non-cohabiting parents and inter-generational contact from children in China. The relationship was also affected by other variables such as demographic factors, socio-economic factors, and current health conditions. Their trend relationship with depression can be shown in Figure 1C-F.

We use the multivariate linear stepwise analysis method to confirm the relationship between the 10 factors with the depression of the non-cohabiting parents in China. 6 models were established. We selected the model6 (P < 0.05) to interpret the variables and depression.

According to the t-value of modle 6 in Table 4, there are six items with significant levels: chronic disease’s number, children’s education, face to face, Children’s income, phone call and genders. In addition, according to the standardized regression coefficient, chronic disease’s number score was the highest, followed by children’s education, and gender is the lowest. It also can be seen from the positive and negative values of regression coefficient that three terms (children education level, income, face to face and phone call) have a negative relationship with depression, which means that the higher the education level of children, the lower the score of depression. The regression coefficient of chronic disease’s number, and genders are all positive, which means that who has the higher the number of chronic diseases, more likely to be depressed.

| Modle | independent variables | Regression coefficient | t | Sig1 | |

| B | Beta | ||||

| Modle 1 | Constant | 11.301 | 0.270 | 41.902 | 0.000b |

| Chronic disease num | 1.249 | 0.126 | 9.921 | 0.000b | |

| Modle 2 | Constant | 14.778 | 0.570 | 25.929 | 0.000b |

| Chronic disease num | 1.207 | 0.125 | 9.667 | 0.000b | |

| Children’s education | -1.084 | 0.157 | -6.907 | 0.000b | |

| Modle 3 | Constant | 13.797 | 0.595 | 23.186 | 0.000b |

| Chronic disease num | 1.229 | 0.124 | 9.889 | 0.000b | |

| Children’s education | -1.093 | 0.156 | -7.006 | 0.000b | |

| Face to face | 0.228 | 0.042 | 5.410 | 0.000b | |

| Modle 4 | Constant | 14.504 | 0.616 | 23.551 | 0.000b |

| Chronic disease num | 1.245 | 0.124 | 10.052 | 0.000b | |

| Children’s education | -0.946 | 0.159 | -5.935 | 0.000b | |

| Face to face | 0.216 | 0.042 | 5.129 | 0.000b | |

| Children’s income | -0.380 | 0.089 | -4.258 | 0.000b | |

| Modle 5 | Constant | 15.414 | 0.696 | 22.136 | 0.000b |

| Chronic disease num | 1.261 | 0.124 | 10.178 | 0.000b | |

| Children’s education | -1.019 | 0.161 | -6.317 | 0.000b | |

| Face to face | 0.202 | 0.042 | 4.758 | 0.000b | |

| Children’s income | -0.421 | 0.090 | -4.668 | 0.000b | |

| Phone call | -0.146 | 0.053 | -2.787 | 0.005b | |

| Modle 6 | Constant | 14.752 | 0.765 | 19.290 | 0.000b |

| Chronic disease num | 1.253 | 0.124 | 10.120 | 0.000b | |

| Children’s education | -1.026 | 0.161 | -6.365 | 0.000b | |

| Face to face | 0.203 | 0.042 | 4.795 | 0.000b | |

| Children’s income | -0.417 | 0.090 | -4.620 | 0.000b | |

| Phone call | -0.142 | 0.053 | -2.707 | 0.007a | |

| Gender | 0.438 | 0.210 | 2.090 | 0.037 | |

This longitudinal study, after analyzing the known confounders, further identified that the risk of depression of mid-aged and elderly people in China who did not live with their adult children was related to the frequency of contact with their adult children, and the optimal frequency of association. Previous studies have indicated that the older people’s social networks affect their physical and mental health by alleviating stress and promoting health-ralated behaviors[18-20]. How does the contact frequency and way impact on depression of the middle-aged and elderly with their adult children? However, few existing studies have quantitatively assessed the effects of such important relationships, and the related conclusions are also inconsistent. An evidence from South Korea indicates that face-to-face and phone contacts are both protective factors for depression between the elderly and non-cohabitating adult children[17]. However, Teixeira et al[21] said that phone call or video online is no substitute for face-to-face visits, as these connections have no effect on reducing the risk of depression in older people.

Our study found that face-to-face and phone contacts are positive factors on depression in non-cohabiting parents in China, which is basically the same as Roh et al[17]’s research, but in terms of the frequency of emotional connection, we get slightly different results from him. Specifically, the more frequent of the intergenerational communication, the lower the depression scores of middle-aged and old people. The frequency of contact between the non-cohabiting parents and their children is a two-way variable and our research suggest that the best frequency of contact is recommended to make a phone call every day and visit 2-3 times a week, if the optimal frequency of contact is not achieved, we suggest that at least one phone call a week and at least visit once every 2 wk, which is an intuitive and operable deadline. Considering the diversification of contact ways related to changes in technological development and the family system, our study examined the differences between phone contacts and face-to-face as well. The results indicated that there was no statistical difference between the group 1 (the frequent face-to-face and frequent phone contact) and the group 3 (infrequent face-to-face and frequent phone contact) in depression scores, and in the four-group comparison, the two groups scores were lower. Therefore, we can conclude that group1 is the best mode of intergenerational emotional connection, but if condition do not allow, group 3 also can reduce the depression of middle-aged and elderly Chinese. While the group 4 (lack of both kinds of contact) showed the highest risk of depression. The results indicated that we should try our best to make face to face and phone contact with our parents, if face to face contact is not achieved, we should make phone contact with our parents as much as possible. Although phone contact could not be conceived as an actual activity, it has the characteristic of higher accessibility in modern China and can provide emotional support to parents. To some degree, with the increasing enrichment of economy and material, these results implied that the emotional needs of non-cohabiting parents are becoming more and more important in the intergenerational communication.

Our study also from the opposite perspective examined the relationship among adult children’s education achievement, income, with depression in non-cohabiting parents in China, and the results revealed that the higher the adult children's education achievement and income, may prone to achieve lower depression score. The possible reasons are as follows: (1) Those who with higher education achievements can get more job options, may easier get relatively satisfactory jobs and high salaries; (2) Higher income provides them with an economic foundation to filial to their parents; (3) Families with children of high achievers will receive praise and respect from the surrounding population, and the parents will feel that their children give them a good name and honor in the neighborhood and achieve a traditional sense of glory, thus gaining happiness and satisfaction in spirit; and (4) With the development of aging and urbanization, many adult children go out to work and separation from their parents, so that the phone contact and money support may be a way of compensation for living apart from their parents[22]. Our study also confirmed these points.

For more reliable results, we also dealt with other variables, such as gender, residence, age, chronic diseases and chronic diseases number. In terms of genders and depression in older adults, our results have been consistent with the existing studies[23-25], that is, women were more prone to depression than men. On residence (urban and rural areas), our study does not have the same conclusions as Hu et al[26,27]. They pointed out that older people in rural areas had more depressive symptoms than those in urban areas, and also have more depressive symptoms than younger people. In terms of age, the highest scores on depression were those from 45 to 50 years old, which was consistent with Weingartner et al[28]’s report on Puerto Ricans. This reversal may be related to the earlier onset of chronic diseases in the population coupled with the multiple social problems of adolescent and young adult children facing the younger respondents. Our research also showed that chronic diseases and the number of chronic diseases could increase the depression scores of the non-cohabiting parents in China. Tang[29]’s views on age, chronic diseases and depression in the old are as follows: age is not a direct factor affecting depression levels in the older adults, but the relationships between age and depression levels are likely to be influenced by other factors, for example health. With the age growing and the decline of health conditions, the depressive symptoms are increasing more. To some extent, our study corroborates this argument, and concludes that the numbers and kinds of chronic diseases are risk factors for depression in non-cohabiting parents.

There are several limitations in this study. On the one hand, we have only used the cross-sectional associations to examine the relationships between contact frequency and depression in non-cohabiting parents in China. On the other hand, CHARLS uses self-report measures which are more prone to measurement errors than clinical or performance assessments. What’s more, contact frequency is not a quantitative variable that can fully explain the relationship between the elderly and their adult children. Therefore, we try to make up for these limitations by distinguishing between phone and face-to-face contacts. And the main variable of contact frequency can be regarded as objective rather than subjective. Therefore, in our research, we strive to minimize the distortion caused by self-report bias to ensure the authenticity of the results.

In summary, our study revealed that a higher frequency of contact from adult children was positively related to fewer depressive symptoms in non-cohabiting parents in China. Under the increasingly severe aging and extensive urbanization conditions in modern China, it is beneficial for the mental health of the non-cohabiting parents by phone contact with their children as much as possible in the absence of face-to-face contact. Next, based on the results of this study, we will formulate specific programs and contents of family emotional support, to verify and improve the programs in further community practice. In order to provide operable suggestions for community work, family intergenerational harmony and the promotion of physical and mental health of the elderly.

China is one of the largest and fastest aging regions in the world and the increasing prevalence of geriatric depression has become a major public health problem.

On the dual changes of population structure and family structure, to explore the impact of intergenerational emotional support on mental health of middle-aged and elderly people.

The aim of the study was to investigate the association between intergenerational emotional support and depression of non-cohabiting parents (≥ 45 years old) in China.

We used the fourth wave data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (2015). 4810 samples were selected according to the purpose of our study, which mainly included data on intergenerational emotional support and the individual scores on depressive symptoms.

The average age was (60.56 ± 14.613) years old. Females were accounted for more than half of the samples (52.6%). 74.0% respondents from rural areas and approximately 63.3% of the participants had a chronic disease. The mean value of the CESD-10 score was 13.06 (SD5.225). Both face to face and phone contacts were protective factors on depression symptoms in Chinese (≥ 45 years old) (P < 0.05). The more frequently you met your parents, the lower your parents' depressive score was. Also, phone contact variable results are displayed as a positive correlation completely between inter-generational contacts from children and depressive symptoms in non-cohabiting parents in China. Children’s education level and income level were also reducing the risk of depression in non-cohabiting parents. However, gender, children’s numerous, chronic disease and chronic disease number were the risk factors.

Intergenerational emotional support is associated with depressive symptoms in non-cohabiting parents in China. However, the relationship was also affected by other variables.

From the perspective of parents to investigate the influence of emotional support of offspring on the mental health of their parents.

This study is based on the baseline of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). We would like to thank everyone who devoted his/her time and effort to the CHARLS project. And we also appreciated the person who have made Suggestions for revision and assistance to this paper.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Wang YP S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Timur S, Sahin NH. The prevalence of depression symptoms and influencing factors among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17:545-551. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Li N, Chen G, Zeng P, Pang J, Gong H, Han Y, Zhang Y, Zhang E, Zhang T, Zheng X. Prevalence of depression and its associated factors among Chinese elderly people: A comparison study between community-based population and hospitalized population. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:87-91. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yu J, Li J, Cuijpers P, Wu S, Wu Z. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults: a population-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:305-312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 114] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | de Paula JJ, Diniz BS, Bicalho MA, Albuquerque MR, Nicolato R, de Moraes EN, Romano-Silva MA, Malloy-Diniz LF. Specific cognitive functions and depressive symptoms as predictors of activities of daily living in older adults with heterogeneous cognitive backgrounds. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:139. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Van de Velde S, Bracke P, Levecque K. Gender differences in depression in 23 European countries. Cross-national variation in the gender gap in depression. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:305-313. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 410] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Åhlin J, Hallgren M, Öjehagen A, Källmén H, Forsell Y. Adults with mild to moderate depression exhibit more alcohol related problems compared to the general adult population: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:542. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bobak M, Pikhart H, Pajak A, Kubinova R, Malyutina S, Sebakova H, Topor-Madry R, Nikitin Y, Marmot M. Depressive symptoms in urban population samples in Russia, Poland and the Czech Republic. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:359-365. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ferlander S, Stickley A, Kislitsyna O, Jukkala T, Carlson P, Mäkinen IH. Social capital - a mixed blessing for women? A cross-sectional study of different forms of social relations and self-rated depression in Moscow. BMC Psychol. 2016;4:37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ehsan AM, De Silva MJ. Social capital and common mental disorder: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:1021-1028. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 171] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5797-5801. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1146] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1220] [Article Influence: 110.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gariépy G, Honkaniemi H, Quesnel-Vallée A. Social support and protection from depression: systematic review of current findings in Western countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209:284-293. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 476] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 519] [Article Influence: 64.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Li J, Cacchione PZ, Hodgson N, Riegel B, Keenan BT, Scharf MT, Richards KC, Gooneratne NS. Afternoon Napping and Cognition in Chinese Older Adults: Findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study Baseline Assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:373-380. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 131] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:61-68. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 961] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1607] [Article Influence: 133.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu Y, Dong W, Xu Y, Fan X, Su M, Gao J, Zhou Z, Niessen L, Wang Y, Wang X. Financial transfers from adult children and depressive symptoms among mid-aged and elderly residents in China - evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:882. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li LW, Liu J, Xu H, Zhang Z. Understanding Rural-Urban Differences in Depressive Symptoms Among Older Adults in China. J Aging Health. 2016;28:341-362. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 126] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Penninx BWJH, Comijs HC. Depression and Other Common Mental Health Disorders in Old Age. In: Newman A, Cauley J. The Epidemiology of Aging. Springer, Dordrecht 2012; 583-598. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Roh HW, Lee Y, Lee KS, Chang KJ, Kim J, Lee SJ, Back JH, Chung YK, Lim KY, Noh JS, Son SJ, Hong CH. Frequency of contact with non-cohabitating adult children and risk of depression in elderly: a community-based three-year longitudinal study in Korea. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60:183-189. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78:458-467. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1941] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1583] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540-545. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3901] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3128] [Article Influence: 86.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kosterina I. Young Married Women in the Russian Countryside: Women's Networks, Communication and Power. Europe-Asia Studies. 2012;64:1870-1892. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Teixeira AR, Wender MH, Gonçalves AK, Freitas Cde L, Santos AM, Soldera CL. Dizziness, Physical Exercise, Falls, and Depression in Adults and the Elderly. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;20:124-131. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Silverstein M, Cong Z, Li S. Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: consequences for psychological well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:S256-S266. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 318] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Riumallo-Herl CJ, Kawachi I, Avendano M. Social capital, mental health and biomarkers in Chile: assessing the effects of social capital in a middle-income country. Soc Sci Med. 2014;105:47-58. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tiedt AD. The gender gap in depressive symptoms among Japanese elders: evaluating social support and health as mediating factors. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2010;25:239-256. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet. 2005;365:1961-1970. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1133] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1045] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hu JS, Xiao J, Bai SY. Subjective well-being of rural elderly. Zhongguo Laonianxue Zazhi. 2006;3:314-317. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Hu Z, Chen RL, Xu XC. Survey on prevalence of geriatric depression and associated factors in rural community. Zhongguo Gonggong Weisheng Zazhi. 2007;23:257-258. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Weingartner K, Robison J, Fogel D, Gruman C. Depression and substance use in a middle aged and older Puerto Rican population. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2002;17:173-193. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tang D. The Mediating Effect of Urban and Rural Residence in the Model of Depression among Chinese Elderly. Population Research. 2010;34:53-63. [Cited in This Article: ] |