Published online May 16, 2015. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i5.474

Peer-review started: August 9, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: November 10, 2014

Accepted: February 10, 2015

Article in press: February 12, 2015

Published online: May 16, 2015

Pheochromocytoma and ganglioneuroma form rare composite tumours of the adrenal medulla comprising less than 3% of all sympathoadrenal tumours. We present a case of intraoperatively detected adrenal medullary tumour of composite pheochromocytoma and ganglioneuroma diagnosed on histopathology, in a normotensive patient. A 50-year-old male with a past history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease presented with abdominal pain and significant weight loss since one month. Ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography abdomen revealed a large lobulated lesion in the distal body and tail of pancreas suggestive of solid and papillary neoplasm of body and tail of pancreas. Intra-operatively, a 15 cm × 10 cm solid lesion with cystic areas was seen arising from the left lower pole of the adrenal gland pushing the pancreas which appeared unremarkable. In our case, exploratory laparotomy with tumour excision was done. Extensive sectioning and microscopic examination of this adrenal tumour confirmed a diagnosis of composite Pheochromocytoma with Ganglioneuroma on histopathology. Immunophenotyping with S-100 further supported the diagnosis. The goal of this report is to increase the awareness of this rare disease and to further identify its variable presentation.

Core tip: Adrenal composite pheochromocytomas may present in various ways without hypertension and conclusive symptoms. We present a case of intraoperatively detected adrenal medullary tumour of composite pheochromocytoma and ganglioneuroneuroma diagnosed on histopathology, in a normotensive patient. The goal of this report is to increase the awareness of this rare disease and to further identify its variable presentation.

- Citation: Gupta G, Saran RK, Godhi S, Srivastava S, Saluja SS, Mishra PK. Composite pheochromocytoma masquerading as solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of pancreas. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3(5): 474-478

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v3/i5/474.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v3.i5.474

Composite tumours of the adrenal medulla combining features of pheochromocytoma and ganglioneuroma are extremely rare. These tumours typically combine features of pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma with those of ganglioneuroma, ganglioneuroblastoma, neuroblastoma, peripheral nerve sheath tumour or neuroendocrine carcinoma. Most cases of composite pheochromocytomas are functional, with symptoms related to increased levels of catecholamines or corticotrophin-releasing hormone or their metabolites. Associated symptoms usually include headache, palpitation, excessive perspiration and hypertension in majority of the cases. We report a case of composite pheochromocytoma with ganglioneuroma in a normotensive patient who presented with an abdominal lump, diagnosed on histopathology clinically masquerading as solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm in tail of pancreas.

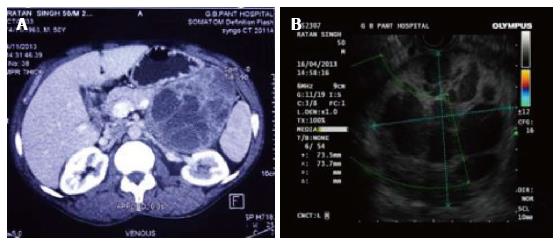

A 50-year-old male, known case of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for 12 years, presented with lump in abdomen associated with pain since one month. He also had history of significant weight loss. There was no associated history of hypertension or diabetes mellitus. On chest examination he had decreased breath sounds in left basal region and expiratory wheeze was noted. Per abdomen examination revealed an ill defined, non-tender mass in the left hypochondrium extending to the left lumbar region. Ultrasound done showed a solid cystic mass which appeared to arise from pancreas. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a lobulated mass lesion measuring 10.8 cm × 8.1 cm × 9.1 cm arising from body and tail of the pancreas suggestive of a solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas (Figure 1A). At endoscopic ultrasound the mass appeared to originate from body of pancreas with displacement of the splenic vessels ( Figure 1B).

Pre-operatively, as per the advice of the chest physician, the patient was stabilised with antibiotics and bronchodilators and further taken up for surgery under moderate risk. Intra-operatively, a highly vascular solid lesion with cystic areas pushing the pancreas, splenic artery and splenic vein upwards probably arising from the retroperitoneum was noticed. Since the patient had fluctuation in blood pressure on handling the tumour, a pheochromocytoma was suspected. Patient was stabilized with nitroglycerine and adrenal infusion and the surgery was completed. Right kidney and adrenal were unremarkable. Post-operatively the patient was extubated on day 2. On Post-operative day 3 (POD-3), the patient started developing breathlessness. He was re-intubated on POD-4 as his blood gas levels deteriorated. Arterial blood gas analysis showed features of type I respiratory failure. The patient died on POD-6.

The surgical specimens were formalin fixed and paraffin embedded. The sections were stained with routine hematoxylin and eosin stain. Immunohistochemical staining was performed by the streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase method and diaminobenzidine as chromogen. The antibodies used included S-100, Synaptophysin, Vimentin, Chromogranin and neurofilament protein. Appropriate positive and negative controls were performed.

Grossly, the left adrenal tumour was well-encapsulated and lobulated measuring 13.5 cm × 10 cm × 6 cm, and weighing 310 g. Cut-surface of the tumour showed multiloculated cystic areas along with a few solid and hemorrhagic areas. Histopathological examination showed a well-encapsulated composite tumour comprising of pheochromocytoma with ganglioneuroma (Figure 2A). The pheochromocytoma component (accounting for 10% of the mass) comprised of polygonal intermediate cells with amphophilic cytoplasm arranged in well-defined nests separated by delicate fibrovascular stroma (Zellballen pattern). These tumour cells had moderate to abundant granular eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm, round to oval nuclei and single prominent nucleoli. The ganglioneuromatous component predominated (accounting for 80%-90% of the mass), and showed sheets of mature ganglion cells surrounded by fascicles of Schwann-like cells (Figure 2B). Areas of haemorrhage and necrosis were noted within the tumour. Normal compressed adrenal was found at periphery.

Immunohistochemically, the pheochromocytoma component was strongly positive for synaptophysin (Figure 2C). However, the gangliocytes were strongly positive for neurofilament protein and vimentin (Figure 2D and E). The sustentacular cells of the pheochromocytoma component and the schwannian cells of the ganglioneuroma component showed characteristic staining of S-100 (Figure 2F). MIB-1 index was noted to be less than 1%.

Composite tumours of the adrenal medulla are rare accounting for less than 3% of sympathoadrenal tumours, and typically comprise of a pheochromocytoma component along with a non-pheochromocytoma component which can include ganglioneuroma, ganglioneuroblastoma, neurofibromatosis-1 and rarely schwannoma. Less than 50 cases have been reported in medical literature. Pheochromocytoma represents a tumour that originates from the adrenal medullary chromaffin cells, while ganglioneuroma is known to originate from autonomic ganglion cells or its precursors. However, both the chromaffin and the ganglion cells arise from a common embryonic progenitor which is the neural crest.

The age range for composite pheochromocytomas is 14-74 years (median 50 years). Patients with composite tumours tend to be older than pure pheochromocytomas. Mostly, 90% of these tumours are localized in the adrenal gland and the remainder in the urinary bladder, organ of Zuckerkandl, or elsewhere in the retroperitoneum. Shawa et al[1] described 9 patients with composite pheochromocytomas and concluded that composite pheochromocytomas; and pheochromocytomas alone are indistinguishable clinically, biochemically and on imaging. Clinically pheochromocytoma can be suspected with its classical symptoms of headache, sweating and palpitations with paroxysmal or sustained hypertension. Kragel et al[2] found hypertension in 4 of 13 patients with composite pheochromocytomas. In a review of composite pheochromocytomas by Khan et al[3], 76.3% were functional. As 3/4th of these patients have symptoms of pheochromocytoma, preoperative biopsy is not advisable. Tischler et al[4] also has similar conclusions stating that the clinical presentation is usually as those of pure pheochromocytomas and so are the profiles of catecholamines and their metabolites. Neural components may cause a watery diarrhea-hypokalemia-achlorhydria syndrome due to increased production of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. However, in our case, a normotensive male patient presented with an abdominal lump with no symptoms referable to pheochromocytoma.

In some patients the absence of endocrine abnormalities and symptoms of pheochromocytoma cannot be explained. One of the reasons for this is the autoregulation of the pheochromocytoma cells by the ganglion cells in the ganglioneuroma component which was first described by Aiba et al[5].

Various imaging modalities can be used to differentiate the pancreatic tumours from adrenal masses and help the clinician to make a precise diagnosis and customize treatment accordingly. Abdominal ultrasound carries a diagnostic sensitivity of 87%-90% and 96% for detecting pancreatic and adrenal tumours respectively[6]. The above results differ slightly with those of other imaging modalities like contrast-enhanced CT, having a sensitivity of 89% and 92% respectively. A fine-needle aspiration biopsy guided by endoscopic ultrasound may provide tissue diagnosis in patients who are not surgical candidates, with a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 100%[7]. Shawa et al[1] in his series of 9 patients described the CT scan features of pheochromocytoma- ganglioneuroma composite tumour (PC-GN). These tumours have 43.5 Hounsfield units (HU) and there was significant enhancement on postcontrast venous-phase imaging. On delayed-phase complete wash out was seen but around 1/3rd of patients showed no washout. Five tumors (83%) were heterogeneous and four tumors (67%) had cystic components. The composite pheochromocytomas cannot be distinguished from pure pheochromocytomas based on CT scan and have similar morphology and pre and post contrast density values[1].

Most case reports that describe composite pheochromocytomas have made diagnosis based on post operative histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry. Thus precise preoperative diagnosis is not possible in composite pheochromocytomas. Immunohistochemically, useful battery of markers include chromogranin A, synaptophysin and catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT). In addition staining for S-100 protein, will identify Schwann cells and sustentacular cells. Neurofilament protein will identify axon like processes.

In the study by Shawa et al[1], the PC-GN composite tumor in one of the patients did not show any growth over 6 years. In addition 6 of their patients had no PC-GN recurrence during a median follow-up of 29 mo according to findings on serial abdominal imaging and/or levels of fractionated plasma-free metanephrine. According to the literature, one in eight patients with PC-GN developed recurrent disease with distant metastasis during a median follow- up of 15 mo[3,8]. Two other reported cases of PC-GN had distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis[1,4]. Including the series by Shawa et al[1] the rate of malignancy in PC-GN composites is almost 8%, compared with 13% to 25% in PC[9,10]. Thus, the presence of a GN composite in PC tumors does not seem necessarily to imply a worse prognosis. Malignancy in pheochromocytomas cannot be confidently predicted on the basis of clinical, biochemical, radiological or histopathological features. The only criterion that may help is the presence of distant metastasis. However, malignant tumours generally have an extraadrenal location, greater tumour weight (> 80 g), larger size (> 5 cm), exhibit high mitotic activity along with vascular/capsular invasion[4]. In our case, the tumour was largely benign as there were no histopathological features suggestive of malignancy, and MIB-1 index was < 1%. The only described treatment is surgical excision and no adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy has been advised[11].

Of the 45 reported cases in the literature, 8 (18%) cases were associated with genetic disorders (6 cases of NF1, 1 case of MEN2A, and 1 case of Von Hipple-Lindau). Kimura et al[12] explained the association between NF1 and PC-GN composites by noting that neurofibromin insufficiency may induce abnormal proliferation of Schwann cells and produce neurotrophins that cause pronounced proliferation of the PC and ganglionic cells through autocrine and paracrine loops. This process eventually results in the formation of composite PC-GNs.

Non hypertensive/non-diabetic 50-year-old man had abdominal pain × 1 mo with anorexia and weight loss. He had an ill defined lump in left hypochondrium and lumbar region.

Body tail pancreatic mass.

Retroperitoneal tumour, renal cell carcinoma.

Laboratory tests were inconclusive.

On ultrasound complex cystic pancreatic body tail mass. Computed tomography scan suggest Solidpseudopappilary mass body tail pancreas supported by endoscopic ultrasound findings.

Composite pheochromocytoma.

He underwent surgical excision of the tumour with intra-operative haemodynamic stabilization with adrenaline and GTN.

Composite pheochromocytomas with ganglioneuromas are rare tumours and less than 50 cases have been reported with 3/4th of the cases having symptoms of pheochromocytoma unlike this case who had only pain abdomen as his main complaint

PC-GN: Pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma.

Composite tumours are rare in occurrence. Although they present with clinical features similar to pheochrocytoma in ¾ cases but asymptomatic tumours can mimic solid pseudopapillary tumours or other retroperitoneal tumours depending upon their location. Imaging characteristics are similar to pheochrocytoma but can have an overlap with solid pseudopapillary tumour. Treatment is surgical excision and they carry a good prognosis.

The case report is interesting and well written.

P- Reviewer: Abdel-Salam OME, Shimada Y, Yokoyama Y S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Shawa H, Elsayes KM, Javadi S, Sircar K, Jimenez C, Habra MA. Clinical and radiologic features of pheochromocytoma/ganglioneuroma composite tumors: a case series with comparative analysis. Endocr Pract. 2014;20:864-869. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kragel PJ, Johnston CA. Pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma of the adrenal. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1985;109:470-472. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Khan AN, Solomon SS, Childress RD. Composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma: a rare experiment of nature. Endocr Pract. 2010;16:291-299. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tischler AS. Divergent differentiation in neuroendocrine tumors of the adrenal gland. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000;17:120-126. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Aiba M, Hirayama A, Ito Y, Fujimoto Y, Nakagami Y, Demura H, Shizume K. A compound adrenal medullary tumor (pheochromocytoma and ganglioneuroma) and a cortical adenoma in the ipsilateral adrenal gland. A case report with enzyme histochemical and immunohistochemical studies. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:559-566. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Kulig P, Pach R, Pietruszka S, Banaś B, Sierżęga M, Kołodziejczyk P. Abdominal ultrasonography in detecting and surgical treatment of pancreatic carcinoma. Pol Przegl Chir. 2012;84:285-292. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Freelove R, Walling AD. Pancreatic cancer: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:485-492. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Kikuchi Y, Wada R, Sakihara S, Suda T, Yagihashi S. Pheochromocytoma with histologic transformation to composite type, complicated by watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, and achlorhydria syndrome. Endocr Pract. 2012;18:e91-e96. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ayala-Ramirez M, Feng L, Johnson MM, Ejaz S, Habra MA, Rich T, Busaidy N, Cote GJ, Perrier N, Phan A. Clinical risk factors for malignancy and overall survival in patients with pheochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas: primary tumor size and primary tumor location as prognostic indicators. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:717-725. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 264] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Goldstein RE, O’Neill JA, Holcomb GW, Morgan WM, Neblett WW, Oates JA, Brown N, Nadeau J, Smith B, Page DL. Clinical experience over 48 years with pheochromocytoma. Ann Surg. 1999;229:755-764; discussion 764-766. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 274] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chrisoulidou A, Kaltsas G, Ilias I, Grossman AB. The diagnosis and management of malignant phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007;14:569-585. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 241] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kimura N, Watanabe T, Fukase M, Wakita A, Noshiro T, Kimura I. Neurofibromin and NF1 gene analysis in composite pheochromocytoma and tumors associated with von Recklinghausen’s disease. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:183-188. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |