Published online May 16, 2015. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i5.457

Peer-review started: October 25, 2014

First decision: December 17, 2014

Revised: February 23, 2015

Accepted: March 16, 2015

Article in press: March 18, 2015

Published online: May 16, 2015

Colorectal lipomas are the second most common benign tumors of the colon. These masses are typically incidental findings with over 94% being asymptomatic. Symptoms-classically abdominal pain, bleeding per rectum and alterations in bowel habits-may arise when lipomas become larger than 2 cm in size. Colonic lipomas are most often noted incidentally by colonoscopy. They may also be identified by abdominal imaging such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. We report a case of a sixty-one years old male who presented to our emergency room with a 6.7 cm × 6.3 cm soft tissue mucosal mass protruding transanally. The patient was stable with a benign abdominal examination. The mass was initially thought to be a rectal prolapse; however, a limited digital rectal exam was able to identify this as distinct from the anal canal. Since the mass was irreducible, it was elected to be resected under anesthesia. At surgery, manipulation of the mass identified that the lesion was pedunculated with a long and thickened stalk. A laparoscopic linear cutting stapler was used to resect the mass at its stalk. Pathology showed a polypoid submucosal lipoma of the colon with overlying ulceration and necrosis. We report this case to highlight this rare but possible presentation of colonic lipomas; an incarcerated, trans-anal mass with features suggesting rectal prolapse. Trans-anal resection is simple and effective treatment.

Core tip: Colorectal lipomas are typically asymptomatic. They are incidentally found on colonoscopy or radiologic imaging. This report portrays a rare presentation of colonic lipomas as an incarcerated prolapsed mass through the anus, and highlights trans-anal resection as a simple, safe and effective treatment. Thus, it describes an uncommon pathology with a unique presentation that sets a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge.

- Citation: Ghanem OM, Slater J, Singh P, Heitmiller RF, DiRocco JD. Pedunculated colonic lipoma prolapsing through the anus. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3(5): 457-461

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v3/i5/457.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v3.i5.457

Lipomas of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract were first described by Bauer in 1757[1]. Although they are rare findings, cases of these benign tumors have been reported throughout the world for many years. Colonic lipomas originate from the connective tissue of the intestinal walls and are most commonly submucosal[2]. Chronic irritation or inflammation as well as the excessive accumulation of adipose tissue secondary to the underdevelopment of arterial, venous and lymphatic circulation, are a few of the speculated factors associated with the formation of these tumors[3]. Lipomas occur with greater frequency within the ascending colon, but can be present in any part of the GI tract from the hypopharynx to the rectum[4]. Generally, colonic lipomas are solitary, well-delineated and sessile masses[5]. They predominately affect females and those within the 6th-7th decade of life[3,6-8]. Although malignancy is rare in these masses, complications including, hemorrhage, infarction, obstruction, and intussusception can occur[2,5,8]. Thus, symptomatic lesions are routinely removed through surgical interventions such as endoscopic excision, segmental resection or hemi-colectomy in an open or laparoscopic fashion[9,10]. Unfortunately, at present there are no clinical trials which validate the most appropriate methods by which colonic lipomas should be diagnosed and treated. Much of patient management is thus dependent on case reports discussed within literature. This paper presents a unique report of a sixty-one years old man with a prolapsed ano-rectal mass that was identified as a submucosal lipoma of the rectum after trans-anal surgical excision. By analyzing this case, we will attempt to review the common practices used in managing patients with colonic lipomas.

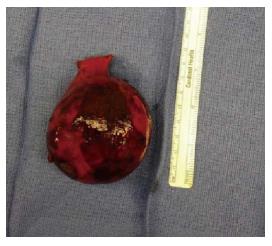

A sixty-one years old male patient with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and chronic constipation presented to the emergency room with a prolapsed ano-rectal mass. The patient noticed the propulsion of the mass while defecating four hours prior to his presentation to our hospital. Associated anal pain and minimal bright red blood per rectum were reported; however, all remaining review of systems was negative. The patient had no previous history of gastrointestinal symptoms or pathologies-denies change of bowel habits and any history of hemorrhoids or prolapse. He had never undergone a colonoscopy. On physical examination, the firm, well circumscribed, tender, hyperemic mass was noted to be 6.7 cm × 6.3 cm in size (Figure 1). There appeared to be a layer of superficial necrotic tissue. It did not appear to be originating from the anus or hemorrhoidal tissue as a limited digital rectal exam was able to identify this as distinct from the anal canal. It was irreducible despite attempts by emergency room and surgical staff (manipulation, squeezing and pushing). Abdominal exam was unremarkable and no systemic signs of infection were noted. Preoperative laboratory studies including hematology, chemistry and coagulation profiles were all within normal ranges. The differential diagnosis included other types of prolapsed neoplastic lesions or an atypical presentation of either thrombosed internal hemorrhoids vs rectal procidentia.

The patient was admitted to the colorectal surgical service. Given the patient’s pain and discomfort and given that the mass was irreducible, the patient was taken to the operation room for exam under anesthesia with planned resection. After sedation, the patient was placed in a high lithotomy position. Digital rectal examination and further manipulation of the mass identified that the lesion was pedunculated with a long (mucosal origin could not be identified) and thickened stalk (2 cm in diameter). As the mass was retracted externally, the stalk could be visualized and was transected by a 60 mm laparoscopic linear cutting stapler (Figure 2). The mass was completely removed and the specimen was sent to pathology. Afterwards, examination of the anus and the distal rectum was performed with an anal retractor. The staple line was not visualized and there existed no active hemorrhage. The bowel was not adequately prepped for endoscopic evaluation so we planned on postoperative colonoscopy after complete bowel preparation.

Post-operatively the patient was stable and denied any pain. He tolerated food, passed gas and also had a bowel movement. The patient was discharged home on post-operative day one with instructions to follow up with a colonoscopy in 2 wk.

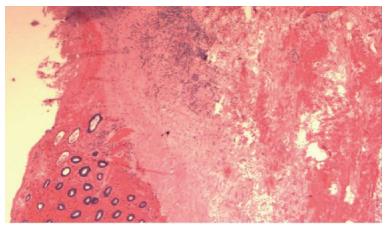

Pathology report determined the mass to be a 6.7 cm × 6.3 cm × 4.8 cm polypoid submucosal lipoma of the colon with overlying ulceration and necrosis (Figure 3). No malignancy was identified.

Lipomas are the second most common benign tumor of the colon after adenomatous polyps[3,5,9] with an incidence of only 0.035%-4.4%[6,9]. Colonic lipomas most commonly occur between the ages of 50-65[3,6-8] and as Jiang et al[6] noted can have up to a 66.7% female predominance. They are most commonly located within the ascending colon (61%)[3,6,7] followed by descending colon (20.1%), transverse colon (15.4%), and least commonly the rectum (3.4%)[3,6,11,12].

Three types of colonic lipomas exist: submucosal, which account for 90% of all intestinal lipomas[2], subserosal and mixed[3]. Grossly, these masses can present as rounded, sessile or pedunculated lesions with smooth mucosal surfaces and a yellow color[3-8]. Histologically, a fibrous capsule is found surrounding the adipose tissue giving the masses a lobulated appearance[3,6]. Ulceration, granulation and fat necrosis has also been noted in the overlying mucosa of many of colonic lipomas[6,8], as identified within the lipoma found in this case report. Over 94% of colonic lipomas are asymptomatic[2,8,13] with many incidentally found during colonoscopic screening, surgery or autopsy[6,9]. Colonic lipomas are more prone to be symptomatic when they are greater than 2 cm in size[4-6,14]. More specifically, 75 percent of patients with “Giant Lipomas”-larger than 4 cm are symptomatic[15]. Symptomatic patients may have abdominal pain (42.4%), bleeding per rectum (54.5%) and alterations in bowel habits (24.2%)[6,7]. Other reported conditions may include constipation, hemorrhage, intussusception, obstruction[2,4,5,8] or anemia[2,4,16,17]. Spontaneous expulsion of these lipomas in the stool has been rarely reported[1,4,9,13,18,19] but is attributed to self-amputation of the lipoma at its stalk[9,20]. Self-amputation typically occurs in giant and pedunclated lipomas and can be caused by intussusception, procedures such as endoscopy or by other idiopathic processes[13,18,19,21].

The rare presentation of colonic lipomas makes the diagnosis a difficult task. They are often misdiagnosed as a rectal prolapse or as a colonic malignancy[3]. One initial radiographic test for colonic lipomas is a barium enema which identifies a well-defined, smooth and radiolucent mass causing an intraluminal filling defect which elongates during peristalsis (the “squeeze sign”)[4,5,7,14]. Unfortunately, although barium enema is sensitive for lipomas, it is not specific to these masses and may mistake them for other endoluminal neoplastic masses[6]. Endoscopic ultrasonography is another commonly used test displaying lipomas as hyperechoic colonic lesions. It is helpful in identifying the involvement of the muscularis propria and serosa[3,5,7,9]. Information regarding the depth of the lesion in the wall of the colon is particularly important in deciding whether the lesion is capable of being safely excised endoscopically.

Three classic signs for colonic lipomas have been described during colonoscopy: the “tent sign” (lifting the overlying mucosa of the lipoma with forceps to create a tent-like shape), the “cushion sign”, (forceps causing indentation of the lipoma which is resolved with their removal) and finally the “naked fat sign” (extrusion of adipose tissue from the lipoma during biopsy)[3,6,14]. However, Andrei et al[3] noted that although colonoscopies are successful in identifying typical lipomas, they are less sensitive for lipomas with atypical qualities such as overlying ulceration or necrosis as seen in the lipoma described in this report. In addition, colonoscopic biopsies often fail to obtain adequate samples of lesions as normal mucosa or even ulcerated and necrotic tissues can cover the adipose tissue necessary for diagnostic testing[6,14]. In situations where obtaining histologic determination of the mass is relevant, needle biopsy under endoscopic ultrasound guidance provides a safe option. The literature indicates that the study of choice for colonic lipomas is computed tomography (CT) scan[3,5,14]. This test visualizes well-defined, ovoid and homogenous intramural lesions with a fat density between -40 and -120 UH[3-5,8]. CT is specifically useful when lipomas are large (> 2 cm)[6,7] and in lipomas with associated complications such as necrosis, infarction or intussusception[2,5,8,22]. Nonetheless, the diagnostic value of CT scan is limited by the size and partial volume of the lesion. Smaller lesions are more likely to be missed by CT while, increases in partial volume, due to the added volume of fecal matter and soft tissue make some masses appear larger than normal on CT imaging[3,14].

The treatment of colonic lipomas involves observation for asymptomatic cases and surgical intervention for lipomas with symptoms or associated complications[23]. Depending on the lipoma size, location and the presence or absence of complications, surgeons decide on endoscopic vs surgical intervention[8]. Endoscopic excision with snare electrocautery is the treatment of choice for lipomas smaller than 2 cm in size[5,6,9,14,23,24]. Higher risk of perforation has been reported with the endoscopic excision of lipomas larger than 2cm in size[6,9]. Newer instrumentation and techniques developed for endoscopic submucosal resection of adenomatous lesions make endoscopic resection more feasible for larger lesions. Segmental colectomy with lipectomy is the gold standard for uncomplicated lipomas larger than 2 cm[3,25]. More radical approaches to resection-hemicolectomy-is usually reserved for lipomas with wide implantable bases, deeper lesions such as those that originate in the subserosal layer, and those with excessive bleeding or associated intussusception[9]. Finally, laparoscopic removal of lipomas is also an available option for treatment[10] and is a superior tool in cases when endoscopic removal is unsafe, ineffective, or cannot obtain negative margins[26]. These surgeries have been found to cause less post-operative pain and quicker recoveries when compared to open colectomies[9,10,13,26-28]. However, Boler et al[26] do acknowledge that laparoscopic resection is limited by the inability to definitively locate certain lipomas. Yet, preoperative colonoscopic injection of a colonic mural marking agent such as india ink or intraoperative colonoscopy can aid in the localization of the lipoma. Overall, surgical intervention is the most effective treatment for colonic lipomas and there have been no reported recurrences in the current literature[9].

In our case, the colonic lipoma was protruding through the anus and was still attached by a viable stalk. To minimize patient morbidity and expedite therapeutic resolution of his symptoms, we resected this incarcerated tumor by a transanal approach. As of the time of creation of this manuscript, the patient has declined colonoscopic evaluation.

Colorectal lipomas most commonly present as asymptomatic, incidental findings on colonoscopy and are treated by either local endoscopic or surgical resection. Our patient demonstrates that they can also present acutely as an incarcerated, trans-anal mass with features suggesting rectal prolapse. We present this case to highlight this possible presentation. Trans-anal resection is simple and effective treatment.

A 61-year-old male patient presented to the emergency room with a prolapsed ano-rectal mass.

A firm, well circumscribed, tender, hyperemic ano-rectal mass was noted to be 6.7 cm x 6.3 cm in size.

Prolapsed neoplastic lesion, thrombosed internal hemorrhoid, rectal procidentia.

Hematology (CBC), Chemistry (BMP) and Coagulation profile (PT INR. PTT) were all within normal range.

Pathology report determined the mass to be a 6.7 cm x 6.3 cm x 4.8 cm polypoid submucosal lipoma of the colon with overlying ulceration and necrosis.

The prolapsed ano-rectal mass was resected trans-anally by the use of laparoscopic linear cutting stapler.

Very few cases of colorectal lipomas were reported with a similar presentation (prolapsed ano-rectal mass) and management (ano-rectal excision).

Lipoma is a benign tumor of the adipose tissue. Rectal procidentia is another term for rectal prolapsed.

The authors report this case to highlight this rare but possible presentation of colonic lipomas; an incarcerated, trans-anal mass with features suggesting rectal prolapse. Trans-anal resection is simple and effective treatment.

The manuscript is well written and the result of the management is acceptable.

P- Reviewer: Alsolaiman MM, Guan YS, Sijens PE S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Ryan J, Martin JE, Pollock DJ. Fatty tumours of the large intestine: a clinicopathological review of 13 cases. Br J Surg. 1989;76:793-796. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kang B, Zhang Q, Shang D, Ni Q, Muhammad F, Hou L, Cui W. Resolution of intussusception after spontaneous expulsion of an ileal lipoma per rectum: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:143. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Andrei LS, Andrei AC, Usurelu DL, Puscasu LI, Dima C, Preda E, Lupescu I, Herlea V, Popescu I. Rare cause of intestinal obstruction - submucous lipoma of the sigmoid colon. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2014;109:142-147. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Kouritas VK, Baloyiannis I, Koukoulis G, Mamaloudis I, Zacharoulis D, Efthimiou M. Spontaneous expulsion from rectum: a rare presentation of intestinal lipomas. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6:19. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nebbia JF, Cucchi JM, Novellas S, Bertrand S, Chevallier P, Bruneton JN. Lipomas of the right colon: report on six cases. Clin Imaging. 2007;31:390-393. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jiang L, Jiang LS, Li FY, Ye H, Li N, Cheng NS, Zhou Y. Giant submucosal lipoma located in the descending colon: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5664-5667. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kose E, Cipe G, Demirgan S, Oguz S. Giant colonic lipoma with prolapse through the rectum treated by external local excision: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:1377-1379. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Mouaqit O, Hasnai H, Chbani L, Oussaden A, Maazaz K, Amarti A, Taleb KA. Pedunculated lipoma causing colo-colonic intussusception: a rare case report. BMC Surg. 2013;13:51. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sidani SM, Tawil AN, Sidani MS. Extraction of a large self-amputated colonic lipoma: A case report. Int J Surg. 2008;6:409-411. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Scoggin SD, Frazee RC. Laparoscopically assisted resection of a colonic lipoma. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1992;2:185-189. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Peters MB, Obermeyer RJ, Ojeda HF, Knauer EM, Millie MP, Ertan A, Cooper S, Sweeney JF. Laparoscopic management of colonic lipomas: a case report and review of the literature. JSLS. 2005;9:342-344. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Katsinelos P, Chatzimavroudis G, Zavos C, Pilpilidis I, Lazaraki G, Papaziogas B, Paroutoglou G, Kountouras J, Paikos D. Cecal lipoma with pseudomalignant features: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2510-2513. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ghidirim G, Mishin I, Gutsu E, Gagauz I, Danch A, Russu S. Giant submucosal lipoma of the cecum: report of a case and review of literature. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14:393-396. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Zhang H, Cong JC, Chen CS, Qiao L, Liu EQ. Submucous colon lipoma: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3167-3169. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kitamura K, Kitagawa S, Mori M, Haraguchi Y. Endoscopic correction of intussusception and removal of a colonic lipoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:509-511. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cirino E, Calì V, Basile G, Muscari C, Caragliano P, Petino A. [Intestinal invagination caused by colonic lipoma]. Minerva Chir. 1996;51:717-723. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Annibale B, Capurso G, Chistolini A, D’Ambra G, DiGiulio E, Monarca B, DelleFave G. Gastrointestinal causes of refractory iron deficiency anemia in patients without gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Med. 2001;111:439-445. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 130] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ginzburg L, Weingarten M, Fischer MG. Submucous lipoma of the colon. Ann Surg. 1958;148:767-772. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gupta AK, Mujoo V. Spontaneous autoamputation and expulsion of intestinal lipoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:833. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Radhi JM. Lipoma of the colon: self amputation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1981-1982. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Bahadursingh AM, Robbins PL, Longo WE. Giant submucosal sigmoid colon lipoma. Am J Surg. 2003;186:81-82. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Triantopoulou C, Vassilaki A, Filippou D, Velonakis S, Dervenis C, Koulentianos E. Adult ileocolic intussusception secondary to a submucosal cecal lipoma. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:426-428. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Goyal V, Ungsunan P. Lipoma of the colon: should asymptomatic tumors be treated? Am Surg. 2013;79:E45-E46. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Kim CY, Bandres D, Tio TL, Benjamin SB, Al-Kawas FH. Endoscopic removal of large colonic lipomas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:929-931. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Waxman I, Saitoh Y, Raju GS, Watari J, Yokota K, Reeves AL, Kohgo Y. High-frequency probe EUS-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection: a therapeutic strategy for submucosal tumors of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:44-49. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Böler DE, Baca B, Uras C. Laparoscopic resection of colonic lipomas: When and why? Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:270-275. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bardají M, Roset F, Camps R, Sant F, Fernández-Layos MJ. Symptomatic colonic lipoma: differential diagnosis of large bowel tumors. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1998;13:1-2. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Saclarides TJ, Ko ST, Airan M, Dillon C, Franklin J. Laparoscopic removal of a large colonic lipoma. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:1027-1029. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |