Published online May 16, 2015. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i5.405

Peer-review started: July 30, 2014

First decision: October 28, 2014

Revised: January 30, 2015

Accepted: February 9, 2015

Article in press: February 11, 2015

Published online: May 16, 2015

Coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus are rare, complex fractures that can be technically challenging to manage. They usually result from a low-energy fall and direct compression of the distal humerus by the radial head in a hyper-extended or semi-flexed elbow or from spontaneous reduction of a posterolateral subluxation or dislocation. Due to the small number of soft tissue attachments at this site, almost all of these fractures are displaced. The incidence of distal humeral coronal shear fractures is higher among women because of the higher rate of osteoporosis in women and the difference in carrying angle between men and women. Distal humeral coronal shear fractures may occur in isolation, may be part of a complex elbow injury, or may be associated with injuries proximal or distal to the elbow. An associated lateral collateral ligament injury is seen in up to 40% and an associated radial head fracture is seen in up to 30% of these fractures. Given the complex nature of distal humeral coronal shear fractures, there is preference for operative management. Operative fixation leads to stable anatomic reduction, restores articular congruity, and allows initiation of early range-of-motion movements in the majority of cases. Several surgical exposure and fixation techniques are available to reconstruct the articular surface following distal humeral coronal shear fractures. The lateral extensile approach and fixation with countersunk headless compression screws placed in an anterior-to-posterior fashion are commonly used. We have found a two-incision approach (direct anterior and lateral) that results in less soft tissue dissection and better outcomes than the lateral extensile approach in our experience. Stiffness, pain, articular incongruity, arthritis, and ulnohumeral instability may result if reduction is non-anatomic or if fixation fails.

Core tip: Coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus are rare, complex fractures that can be technically challenging to manage. Distal humeral coronal shear fractures may occur in isolation, may be part of a complex elbow injury, or may be associated with injuries proximal or distal to the elbow. This article aims to summarize the classification, evaluation, management (including surgical approaches, techniques, and post-operative care), and complications of these complex fractures as well as give recommendations on the management.

- Citation: Yari SS, Bowers NL, Craig MA, Reichel LM. Management of distal humeral coronal shear fractures. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3(5): 405-417

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v3/i5/405.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v3.i5.405

Coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus are rare, complex fractures that can be technically challenging to manage[1-3]. They usually result from a low-energy fall and direct compression of the distal humerus by the radial head in a hyper-extended or semi-flexed elbow or from spontaneous reduction of a posterolateral subluxation or dislocation[2,4,5]. Due to the small number of soft tissue attachments at this site, almost all of these fractures are displaced[2]. The incidence of distal humeral coronal shear fractures is higher among women because of the higher rate of osteoporosis in women and the difference in carrying angle between men and women[2,6-11]. Distal humeral coronal shear fractures may occur in isolation, may be part of a complex elbow injury, or may be associated with injuries proximal or distal to the elbow[2,6-10]. An associated lateral collateral ligament injury is seen in up to 40% and an associated radial head fracture is seen in up to 30% of these fractures[2,9,12]. Stable internal fixation restores articular congruity and allows initiation of early range-of-motion movements in the majority of cases[1-3]. Several surgical exposure and fixation techniques are available to reconstruct the articular surface following distal humeral coronal shear fractures. A lateral extensile approach and fixation utilizing countersunk headless compression screws placed in an anterior-to-posterior fashion are commonly used[1-3,7-10]. Stiffness, pain, articular incongruity, arthritis, and ulnohumeral instability may result if reduction is non-anatomic or if fixation fails[3]. We present several methods including a two incision method technique utilizing a direct lateral approach combined with a direct anterior approach. This paper aims to review the literature regarding distal humeral coronal shear fractures and to discuss approach and treatment techniques for these difficult fractures. The search algorithm and search criteria included any original and review articles on the topic of distal humeral coronal shear fractures.

The most common classification of capitellar fractures is the expanded Bryan and Morrey’s types I-IV. Type I (Hahn-Steinthal) consists of a large fragment of trabecular bone of the articular surface of capitellum and with little to no extension into the lateral trochlea. The type II (Kocher-Lorenz) fracture is limited to the cartilaginous articular surface of the capitellum that may include a small fragment of subchondral bone. Type III (Broberg-Morrey, Grantham) is a comminuted/compression fracture of the capitellum[13]. Type IV fracture, later described by McKee, is a shear fracture of the distal end of the humerus that extends in the coronal plane across the capitellum to include most of the lateral trochlear ridge and the lateral half of the trochlea[14].

More recent attempts at distal humeral fracture classifications have attempted to characterize capitellar fractures in a manner meant to direct surgical management and potentially predict outcome of injuries. Dubberley et al[9] classified capitellar fractures into three types. Type 1 involving primarily the capitellum with or without lateral trochlear ridge, described as a coronal shear fracture equivalent to Hahn-Steinthal. Type 2 is a fracture of capitellum and trochlea in a single piece where the fracture extends in the coronal plane across the capitellum to include most of the lateral trochlear ridge and the lateral half of the trochlea-essentially McKee’s-described type IV Bryan and Morrey fracture. Lastly, type 3 involves fractures of both the capitellum and the trochlea as separate fragments. The fractures are further subdivided into type (A) or (B) depending on absence or presence of posterior condylar comminution, respectively[2,3,9].

Ring et al[8] also proposed a five-type system of capitellar fracture classification based on noted injury patterns given that isolated coronal shear fractures were described as rare[2,3,8]. The five types progressively include more distal humeral involvement beginning with Type 1, a coronal shear fracture comprised of single articular fragment that includes the capitellum and the lateral portion of the trochlea. Type 2 includes an associated fracture of the lateral epicondyle. Type 3 involves a further impaction of the metaphyseal bone behind the capitellum in the distal and posterior aspect of the lateral column. Type 4 adds a fracture of the posterior aspect of the trochlea. Finally, type 5 includes a fracture of the medial epicondyle[8].

Evaluation of a patient with a distal humeral coronal shear fracture involves clinical assessment and radiography[1]. A radiographic elbow trauma series consisting of AP, lateral, and radiocapitellar views as well as radiographic images of the wrist and forearm should be obtained requisitely[3]. The double-arc sign on lateral X-ray (Figure 1) of the elbow is pathognomonic of a fracture with substantial extension into the trochlea (McKee’s type IV fracture in the Bryan and Morrey classification)[1,2,14]. However, X-rays only have a 66% sensitivity and a negative predictive value of only 63%-67% for detecting fractures beyond the capitellum[1,2,4]. For this reason, a preoperative CT scan of the elbow is recommended to better define the fracture and associated injuries and to guide operative planning[1,2,4,7,14,15]. A thorough neurovascular exam of the upper extremity, assessment of the forearm compartments, and a secondary musculoskeletal survey should always be performed in these patients[3]. Pain and guarding will limit assessment of elbow stability in the office setting or emergency department. As a result, thorough elbow assessment should be conducted at the time of surgical intervention under anesthesia[3]. In general, obtaining imaging of a joint above and below the level of injury will usually reveal bony injuries, but soft tissue injuries require a high index of suspicion and physical examination. This includes palpation of the entire extremity with particular focus on the distal radial ulnar joint and rotator cuff[3,16]. Follow-up examination and MRI scanning may be needed particularly of the shoulder[16].

Non-surgical management of coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus is reserved only for patients not medically fit for surgery. Otherwise, it is not recommended to treat these fractures non-surgically. Non-operative treatment would involve closed reduction with prolonged immobilization. Such measures often lead to suboptimal results and complications such as chronic pain, mechanical symptoms, and instability[1-3].

The goal of surgery is to restore articular congruity and obtain stable fixation, allowing for early range-of-motion to minimize the sequelae associated with non-op treatment: arthritis, pain, stiffness, and instability[2]. Surgical options include open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), excision, total elbow arthroplasty, and arthroscopic reduction and fixation[2]. These types of surgical treatment and their indications are discussed individually below.

ORIF results in good to excellent outcomes [measured by the Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS)] in the majority of patients with coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus[1,2]. Based on many studies, the mean flexion-extension arcs after ORIF of a distal humeral coronal shear fracture range from 96o to 132o[1,3,6-9,17]. Superior results with ORIF are attributed to the fact that it allows anatomic reduction with stable fixation and thus initiation of early range-of-motion exercises[1].

ORIF involves opening the skin via a particular surgical approach (discussed in a separate section) to visualize and subsequently fix the fracture. There is currently no consensus on the optimal method of fixation for coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus. Countersunk headless compression screws (along with plate supplementation on the lateral column in cases of comminution extending beyond the articular surface) have been used with success[1,2,7,8,10]. Ruchelsman et al[3] recommend placing two screws in a divergent fashion for a Ring’s type I fracture to ensure rotational control, with sufficient screw spread to avoid iatrogenic fracture of the capitellum. Ring’s Type II and III fractures (posteroinferior/lateral metaphyseal comminution and/or trochlear extension) often require supplemental fixation[3,7-9,18]. This can be accomplished using minifragment Synthes screws (West Chester, PA), threaded K-wires, and bioabsorbable pins for osteochondral capitellum and trochlea fractures < 5 mm, and pelvic reconstruction, precontoured or locking plates to buttress the lateral column in cases of extensive posterolateral comminution[3,8,9,18]. A biomechanical analysis by Elkowitz et al[19] has shown that placing headless compression screws in an anterior-to-posterior fashion is superior to placing cancellous screws in a posterior-to-anterior fashion. A follow-up study showed that Acutrak headless compression screws (Acumed, Hillsboro, OR) offered more stability than Herbert screws (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) when placed in an anterior to posterior fashion[20]. Placing screws anterior-to-posterior is advantageous because it avoids disruption of the posterior soft tissues and allows better preservation of blood supply[1,21]. Sen et al[22] described placing screws in a lateral to anterior fashion to avoid posterior stripping, in addition to an anterior antiglide plate for the capitellum. When posterior comminution is present, supplemental fixation with bone graft might be necessary[2,7-9]. A recent study by Lee et al[23] found no significant difference in terms of clinical outcomes and complication rates between orthogonal and parallel plating methods for distal humeral fractures. However, the authors of the study state that orthogonal plating may be preferred in coronal shear fractures (where the posterior-to-anterior fixation can provide additional stability to the intra-articular fractures). Additional studies are needed to explore the association between plating methods and specific fracture patterns.

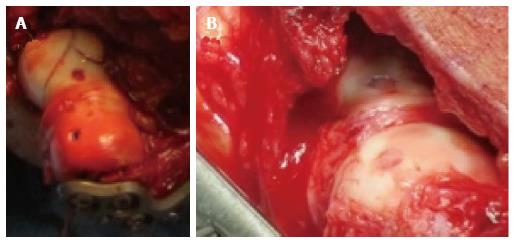

Our preferred method is to use headless compression screws placed in an anterior-to-posterior fashion with or without a lateral plate for the fixation of coronal shear fractures. There is a Grade C recommendation for this method[1]. Figure 2 shows the appearance of holes created by headless compression screws right after (Figure 2A) and several months after (Figure 2B) insertion.

Capitellar excision is another option in the treatment of distal humeral coronal shear fractures. This method is associated with complications such as substantial elbow instability, particularly when there is ligamentous injury or the trochlea is involved[1-3]. Grantham et al[24] and Mancini et al[25] reported poor clinical outcomes and valgus instability plus distal radioulnar joint subluxation, respectively, following capitellar excision. Excision remains an option for small, unfixable fractures, but ORIF should be utilized instead whenever possible[2].

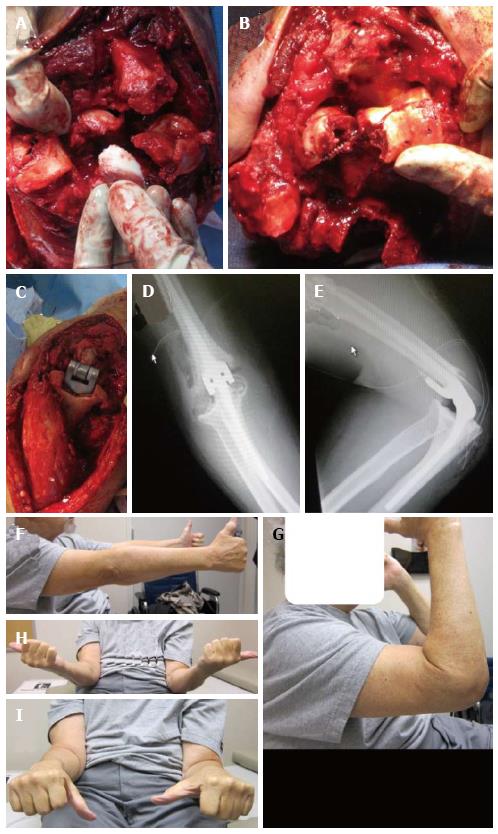

Total elbow arthroplasty is a good option in select elderly patients with fractures deemed unrepairable (Figure 3)[2,26-29]. This is particularly relevant to patients with pre-existing arthritis of the elbow[1,30,31]. McKee et al[28] conducted a prospective, randomized, multicenter study in which they compared ORIF with total elbow arthroplasty in forty patients over the age of sixty-five years with displaced, comminuted, intra-articular fractures of the distal humerus. They reported better functional outcomes at two years post-operatively in the group with total elbow arthroplasty based on MEPS and DASH scores. Furthermore, five out of twenty patients (25%) in the ORIF group had to undergo intra-operative conversion to total elbow arthroplasty due to extensive comminution and an inability to achieve stable fixation.

When acute total elbow arthroplasty is anticipated or being considered, it is critical to avoid the olecranon osteotomy operative approach (discussed in a separate section). This approach compromises fixation of the olecranon component and is contraindicated for total elbow arthroplasty[1,28]. Reichel et al[29] reported a case in which an ORIF had to be immediately converted to a total elbow arthroplasty following an olecranon osteotomy.

Overall, there is fair evidence that acute total elbow arthroplasty is the preferred treatment for elderly patients (> 65 years of age) with a displaced, comminuted, intra-articular distal humeral coronal shear fracture that is not amenable to stable internal fixation. This gets a grade B recommendation[1].

A case report by Hardy et al[32] described arthroscopic-assisted reduction and screw-fixation of a type I Hahn-Steinthal capitellum fracture using one viewing portal and two instrumentation portals. According to many authors, arthroscopic reduction and fixation techniques for coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus should be reserved only for simple fractures without comminution (such as type I in the Dubberley or Bryan and Morrey classification)[2,32-35].

After surgical intervention, the patient is put in a long-arm posterior plaster splint or compressive dressing if rigid fixation has been achieved. The patient is usually seen for his/her first post-operative office visit between seven and ten days post-operatively. The splint and/or compressive dressing are usually removed at this visit. Active and active-assisted range of motion of the elbow and forearm along with formal therapy is also initiated after the first office visit[3].

If the fixation achieved intra-operatively is suboptimal, the patient may be put in a functional brace[3]. If there is concomitant ligamentous or functionally equivalent osseous injuries, then mobilization in pronation is established for lateral-sided injuries and mobilization in supination is established for medial-sided injuries[3,36,37]. When clinical and radiographic evidence of fracture union is evident, strengthening exercises can be initiated[3].

When there is concern about the stability of fixation, delayed or protected mobilization with a hinged elbow brace or cast may be necessary. A hinged brace with gradual reduction of the extension block allows maintenance of radial head congruity with the reduced capitellum. When flexion contracture occurs in the early post-operative period, extension thermoplastic splinting is used[3]. Gelinas et al[38] showed that turn-buckle splinting is effective in regaining ulnohumeral motion. If ulnohumeral motion remains poor and there is flexion contracture present, a contracture release can be performed[3].

The operative treatment described in majority of publications is performed through the extended lateral Kocher approach. Most authors advocate the extended lateral Kocher approach for fractures without significant posterior comminution or medial column damage[8,10,39].

In the extended lateral approach, the patient is positioned supine and the arm is controlled with a tourniquet. An incision is made from the lateral supracondylar ridge extending over the lateral epicondyle to 2-5 cm distal to the radial head. The common extensor origin is elevated anteriorly. The lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL) should only be elevated if necessary to obtain sufficient exposure of the fracture[8,9,12,14,40-42]. In our practice, we have abandoned elevating the LUCL and place any plates we may use directly over the ligament. If there is an associated fracture of the lateral epicondyle, the fragment should be retracted with the disrupted LUCL[8,43]. In such cases, place a suture through the LUCL; this allows reattachment through holes drilled in the lateral epicondyle after fracture fixation[14]. We commonly suture the LUCL directly over the plate if the ligament is torn or has been elevated.

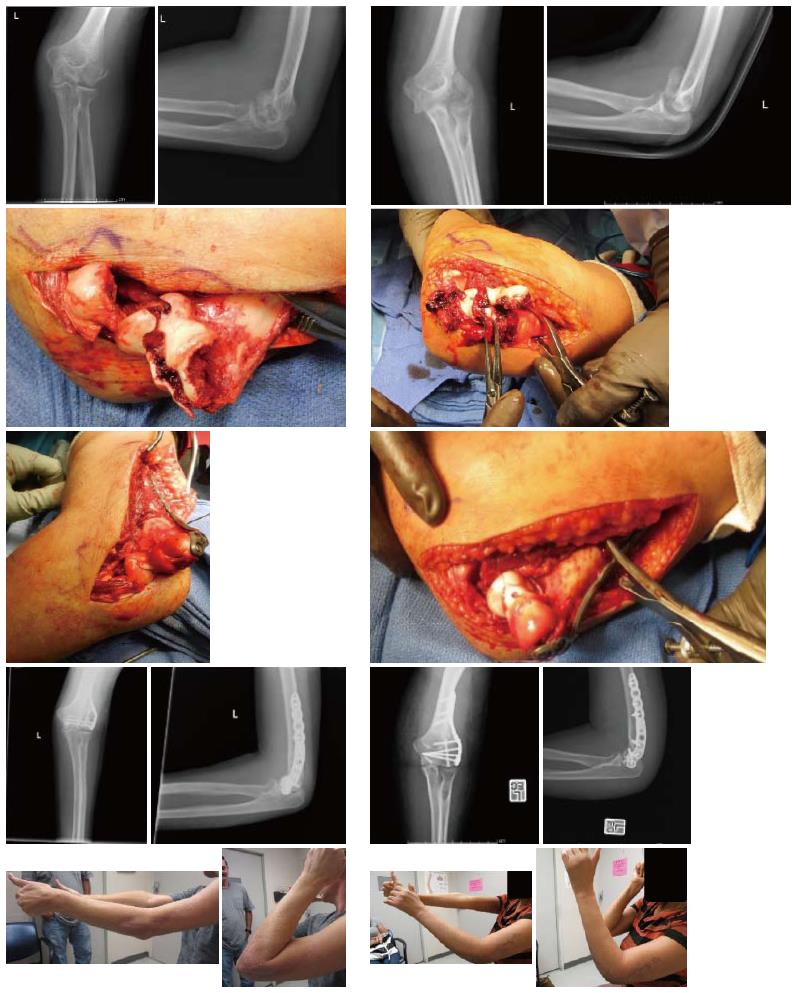

The incision is then extended between the biceps and triceps proximally and between the anconeus and extensor carpi ulnaris distally. The forearm is then pronated to protect the posterior interosseus nerve (PIN) and the common extensor origin is elevated to create a soft tissue flap. This flap constitutes the vascular supply of the posterior distal humerus and capitellum[12]. The anterior joint capsule can now be elevated and retracted to expose the capitellum and trochlea[14]. The lateral extensile approach is seen in Figure 4 (the 2nd row pictures of both columns). Anterior retractors over the radial neck increase risk of injury to the PIN and should be avoided[12].

Intraoperative difficulty achieving anatomic reduction often signifies posterior comminution of the lateral column not apparent on radiographs. In such cases, and with known posterior comminution, the distal lateral triceps should be reflected from the olecranon to allow the elbow to hinge open, exposing the posterior lateral column[8]. Additionally, some authors elected to use a supplemental posterior midline incision in cases when the medial trochlea could not be visualized well with the extended lateral approach alone[8,42].

The posterior approach with an olecranon osteotomy can be used when an articular fracture extends to the medial epicondyle and when there is significant posterior comminution or medial column damage[8,10,17,39]. Additionally, a posterior approach without osteotomy is recommended if future procedures or arthroplasty is anticipated[10]. Dubberley et al[9] recommend a posterior approach for all coronal shear fractures with an olecranon osteotomy for some type 2 fractures, and most type 3 fractures.

In the olecranon osteotomy approach, the patient is positioned in the lateral decubitus position with the arm over a bolster and controlled with a tourniquet. A posterior midline incision is made and a single or multiple intermuscular planes are developed to access the capitellum. Lateral planes described in the literature include the Boyd, Kocher, and Kaplan exposures[9,44-46]. Patients with Dubberly type 1 fractures-coronal shear fractures of capitellum and a part of lateral trochlear ridge-can be managed without disruption of the LUCL, a second medial plane, or an olecranon osteotomy[9].

Dubberly type 2 fractures-single fragment fractures of the capitellum that extend into the trochlear groove-often require a second intermuscular exposure through a medial flexor pronator split in order to access the medial trochlea. If reduction remains difficult, it is necessary to disrupt the LUCL allowing the joint to hinge open on the medial collateral ligament. The LUCL should be repaired after fixation using drill holes and a locking suture technique. However, the LUCL should be preserved whenever possible to avoid the risk of instability following repair[9,43].

An alternative to LUCL disruption is an olecranon osteotomy. Dubberly type 3 fractures-comminuted shear fractures of the capitellum and trochlea-often require olecranon osteotomy. After elevation of fasciocutaneous flaps, the ulnar nerve is identified and protected. Then, a chevron osteotomy is created over the olecranon through the bare area. An oscillating saw is used to cut two thirds of thickness of bone and the remaining attachment is carefully separated using an osteotome[8]. We typically place sponge in the ulnohumeral joint and saw directly to the sponge to minimize the kerf of bone removed. This exposes the anterior articular fragments for fixation. The olecranon fragment can be repaired after fracture fixation with two Kirschner wires directed anteriorly to the distal coronoid process and one 18 gauge or two 22 gauge figure of eight tension band wires[8]. Alternatively, the olecranon fragment can be repaired with plate and screw fixation[9].

In studies published to date there are no significant differences in outcomes between the extended lateral approach and the posterior midline approach[3,12,14,17,39]. Given that an olecranon osteotomy creates increased risk of non-union and symptomatic hardware, the procedure is only used for large and or comminuted fractures[9,17].

A few authors advocate for an anterolateral approach because it exposes the capitellum and the trochlea without disruption of the LUCL or an olecranon osteotomy[47,48]. One advocate of this approach recommends an extended lateral approach for isolated fractures of the capitellum and an anterolateral approach for fractures with involvement of the trochlea[47].

In this procedure the patient is positioned supine and the arm is controlled with a tourniquet. An incision is made 7 cm proximal to the flexion crease of the elbow between the biceps and brachioradialis and extended along the lateral border of the biceps. At the elbow the incision curves laterally to avoid scarring perpendicular to the flexion crease. The incision continues along the medial border of the brachioradialis 7 cm distal to the flexion crease. The radial nerve is identified and retracted laterally with the brachioradialis. The biceps is reflected medially exposing the anterior joint capsule which is incised vertically. Flexion exposes the capitellum for fracture fixation[47].

Malki et al[48] propose a more limited anterolateral exposure with an additional posterolateral stab incision for isolated capitellar fractures. In this approach, an incision is made over the lateral epicondyle and the anterior lateral joint capsule is incised longitudinally. This exposed fracture is manually reduced. Next, a threaded guide wire is inserted radially and directed perpendicular to the fracture. An additional stab incision on the posterior lateral elbow allows for fixation radially and posteriorly. A second wire is advanced parallel to the first wire through this incision until it nearly elevates the articular cartilage. A cannulated drill bit and tap are advanced over the wires and a short cannulated screw is inserted over the wire for definitive fixation[48].

There have been four cases reported on arthroscopic repair of coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus: three Dubberly type 1A fractures and one type 3A fracture[32,34,35]. Advocates of arthroscopic fixation report less soft tissue injury and decreased risk of devascularization, infection, and elbow contracture compared to ORIF[32,35]. However, the type 3A fracture that underwent arthroscopic repair developed avascular necrosis at one-year follow up[34]. It has been demonstrated that arthroscopy is a technically difficult but feasible approach for fixation of single fragment coronal shear fractures of the capitellum without comminution or significant involvement of the trochlea[32,34,35]. Given the limited evidence, authors advocate for judicious use of arthroscopic fixation for coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus[34]. It is not possible to perform an adequate comparison of the arthroscopic approach to the extended lateral or the anterolateral approach because there are so few cases in the literature.

In the procedure, the patient is placed in lateral decubitus position, the elbow is flexed to 90 degrees and controlled with a tourniquet. Three incisions are made on the lateral elbow: one for a fluid control system to distend the joint, a second for instrumentation, and a third for the arthroscope. The joint is lavaged and fracture site cleaned with a shaver. The fracture fragment is reduced with a punch and held in place with a K wire prior to fixation with cannulated screws advanced through the articular cartilage[32]. Alternatively, the fracture can be reduced using a K wire and definitively fixed with screws advanced over guide pins perpendicular to the fracture[34,35].

In order to minimize the total soft tissue dissection we have developed a two-incision technique (Figure 5). Of note, we prefer to use a headlight during this procedure. A lateral incision is made over the supracondylar ridge extending distal over the suspected extensor digitorum communis (EDC) tendon. Full thickness fasciocutaneous flaps are raised. The dissection proceeds in between EDC and extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB). The supinator is then elevated off the radial head/neck junction sharply retaining the annular ligament and anterior capsule below undisturbed. A sharp capsulotomy is performed along the lateral distal humerus, stopping at the annular ligament [anterior to the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) insertion], just enough to visualize the fracture. If the capsule is tight and we cannot see the fracture, we divide the annular ligament anterior to the radial portion of the LCL (which lies directly beneath the EDC tendinous origin) to improve our visualization of the fracture[49].

We take great care not to dissect or elevate the LCL. If the fracture is comminuted, there is frequently a shell of bone attached to the LCL. Even in such cases, we do not elevate the LCL but rather apply plate fixation directly over it. Large capitellar fracture fragments are then fixed with headless compression screws. Small, comminuted fragments (usually posterior) are excised if present. We then view the medial extent of the fracture through this lateral incision. At this time, we make an anterior approach as previously described for fixing coronoid fractures[50] but with a more limited dissection to the distal humerus[50,51].

An incision of approximately 3 cm is made beginning at the elbow crease. Dissection proceeds between biceps and the neurovascular bundle. A finger is used to palpate the trochear fracture fragments (typically larger fragments). The brachialis is split at the level of the trochlear fragments through the anterior approach. A longitudinal capsulectomy is then made and the fracture’s trochlear fragments are reduced under direct visualization and fixed with headless compression screws. The reduction can be provisionally fixed with several 0.054 K-wires and confirmed through both the lateral and anterior approach prior to placing the headless compression screws. Lateral comminution is addressed by applying a buttress plate directly over the LCL if needed. Fractured fragments are stressed manually and visualized throughout range of motion for stability.

The following recommendations for care are adapted from a 2011 review article by Nauth et al[1], who conducted a thorough literature search on the topic of distal humeral fractures: (1) Grade C recommendation for the use of CT scanning in the assessment of coronal shear fractures; (2) Grade C recommendation for ORIF of all displaced coronal shear fractures in patients for whom surgery is suitable; (3) Grade C recommendation for the use of a lateral extensile approach for the fixation of the majority of coronal shear fractures; (4) Grade C recommendation for the use of headless compression screws placed in an anterior-to-posterior fashion for the fixation of coronal shear fractures; (5) Grade B recommendation for acute total elbow arthroplasty in patients > 65 years of age with displaced, comminuted, intra-articular distal humeral fractures not amenable to stable internal fixation; and (6) Grade B recommendation for initiation of early range-of-motion exercises (within 2 wk) following ORIF of distal humeral coronal shear fractures.

Grades of recommendation: (1) A = Good evidence from Level-I studies with consistent findings; (2) B = Fair evidence from Level-II or III studies with consistent findings; (3) C = Poor-quality evidence from Level-IV or V studies with consistent findings; and (4) I = Insufficient or conflicting evidence[1,52].

Good to excellent outcomes have been reported for the majority of patients who have undergone ORIF following a distal humeral coronal shear fracture. Outcomes are particularly good when the fracture is isolated to the radiocapitellar compartment[2,3,6-10,12]. One can expect mean pronosupination arcs of 156° to 180°, flexion-extension arcs of 96° to 141°, and flexion contractures of 10° to 28° for these fractures after ORIF[2,6-8,12,14,17,47]. Figure 5 shows one of our patients who achieved excellent outcomes in terms of range-of-motion following ORIF of a distal humeral coronal shear fracture. Of note, we utilized the two-incision technique described above for this patient.

Fractures with significant medial extension or comminution don’t do as well, with non-unions occurring in the worse fracture subtype[2,6,9-11,14,47,53]. Dubberley et al[9] conducted a cohort study (n = 28) which found significantly inferior functional elbow evaluation scores (based on the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons function score and Mayo Elbow Performance Index) with Dubberley type II (medial trochlear extension) and Dubberley type III (capitellum-trochlea comminution) fractures compared to type I fractures[9]. In another study by Ruchelsman et al[3,7], patients with McKee type IV fractures had significantly reduced terminal flexion and net ulnohumeral arc and larger flexion contracture compared to patients with type I fractures at two years post-operatively[3,7]. The differences in outcome between the different fracture types may be due to increased severity of injury and/or to the extended surgical approach needed to facilitate exposure in the worse fracture types[3].

Satisfactory clinical and functional outcomes have been reported by some authors following ORIF of McKee’s type IV fractures[3,7,10,11,14,47]. Despite a mean postoperative flexion contracture of 14.5° to 17.5°, a functional arc of ulnohumeral motion is achieved in most of these patients[3,7,14,47].

In a subcohort analysis of 16 patients with distal humeral coronal shear fractures, 5 out of 16 had a concomitant radial head fractures (Mason type I and type II)[7]. At a mean of 27 mo postoperatively, 2/5 had excellent outcomes, 2/5 had good outcomes, and 1/5 had a fair outcome (based on Mayo Elbow Performance Index). However, compared to the 11 remaining patients with an isolated capitellum and trochlea fracture, patients with concomitant ipsilateral radial head fractures had greater loss of terminal flexion and extension and reduced ulnohumeral arc of motion[3,7]. However, since the sample size in this study was very small, statistical significance cannot be reached and larger cohort studies are needed to compare outcomes of fractures with concomitant radial head fracture with those of isolated capitellum and trochlea fractures following ORIF[3].

A study by Guitton et al[6] found good to excellent outcomes in 13 out of 14 (93%) patients at long-term follow-up (median of 17 years) following operative fixation of distal humeral coronal shear fractures. This study shows that outcomes following ORIF are durable[2].

Complications following ORIF of distal humeral coronal shear fractures in the early post-operative period include stiffness, pain, loss of fixation, instability, infection, neurologic complications (i.e., ulnar neuritis), and hardware complications[3]. Arthritis, malunion, nonunion, avascular necrosis and heterotopic ossification represent complications that can arise later. Overall, complications other than stiffness are rare[2].

Dubberley et al[9] found 7 out of 17 patients status post ORIF for Dubberley type II or III fractures who had elbow contracture with less than functional ulnohumeral motion. Figure 4 compares two patients with similar fractures, one of whom had a good outcome while the other developed severe stiffness and range of motion deficits status post ORIF. It is more important to maintain articular congruity than it is to prevent flexion contracture. The latter, a complication sometimes seen following ORIF of coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus, can be later addressed with contracture release[2]. In a series by Ring et al[8], 8 out of 21 patients required a contraction release. There was a mean increase of 42o in ulnohumeral motion following the release. In this same series, two patients who had undergone ORIF through an extended lateral approach developed ulnar neuropathy which required decompression and transposition. According to Ruchelsman et al[3], olecranon osteotomies have been associated with rare hardware complications (such as impingement of hardware in the radiocapitellar joint) which may necessitate screw removal.

Mild to moderate degenerative changes have been reported in patients having undergone ORIF for distal humeral fractures[3,7,9]. Of 14 fractures treated with ORIF, only seven had Broberg and Morrey radiographic grade I or II arthritis and two had grade III arthritis at a median 17-year follow-up[2,6,8,9].

In a series by Brouwer et al[53], 8 out of 18 (44%) patients with Dubberley type IIIB fractures developed radiographic nonunion while none (0 out of 12) with Dubberley type IIA or IIB fractures developed nonunion. Of the 8 that developed nonunion, two had infections and were thus considered as failures. The remaining six had good to excellent results in half and fair results in the other half. There was no difference in range of motion compared to the patients who achieved union[2,53]. Dubberley et al[9] reported two patients status post ORIF for a type III fracture that developed nonunion and had to be converted to total elbow arthroplasty. Total elbow arthroplasty is a salvage option for nonunion/malunion as well as for severe symptomatic post-traumatic arthrosis, articular osteonecrosis, and elbow instability[3].

In a recent study by Lee et al[23], only five out of sixty-seven patients with distal humeral fractures developed some degree of heterotopic ossification following ORIF. However, of these patients, only one developed a functional deficit (this patient had suffered from a high trauma injury and had a delayed operation). Overall, clinically significant heterotopic ossification is uncommon and there is insufficient evidence to recommend a prophylactic regimen against this complication[1-3].

The aim of this paper was to review the literature on the topic of distal humeral coronal shear fractures and to present several approach and treatment techniques.

Coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus represent significant articular injuries and are usually more complex than suggested by radiographic imaging. CT scans are therefore highly recommended for preoperative assessment of these fractures and treatment planning. The fracture pattern and extent of articular involvement dictate method of surgical exposure and internal fixation technique used for treatment. Open reduction internal fixation through lateral extensile exposures or posterior exposures using variable-pitch, headless compression screws is the treatment of choice for simple fracture types, leading to good to excellent outcomes in the majority of cases. Additional extensile exposures, LUCL disruption, olecranon osteotomy, bone grafting, and supplemental fixation using minifragment screws, column plating, and/or bioabsorbable implants may be required for more complex fracture types. We have found a two-incision approach (lateral and direct anterior) results in less soft tissue dissection and damage than the extensile approaches. Coronal shear fractures with substantial medial extension and posterior comminution generally have worse outcomes. The most common complication following ORIF of these fractures is stiffness (flexion contracture). It should be noted that the literature on distal humeral coronal shear fractures is comprised mainly of level-III and IV studies. Consequently, more prospective, multicenter, large-scale trials are needed to assist surgical decision-making in the future. Furthermore, longer-term data are needed to fully evaluate the incidence and severity of rare complications such as arthritis, osteonecrosis, and heterotopic ossification following these fractures.

P- Reviewer: Sadoghi P S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Nauth A, McKee MD, Ristevski B, Hall J, Schemitsch EH. Distal humeral fractures in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:686-700. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 129] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee JJ, Lawton JN. Coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:2412-2417. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ruchelsman DE, Tejwani NC, Kwon YW, Egol KA. Coronal plane partial articular fractures of the distal humerus: current concepts in management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:716-728. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Watts AC, Morris A, Robinson CM. Fractures of the distal humeral articular surface. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:510-515. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF, Korinek S, An KN. Elbow subluxation and dislocation. A spectrum of instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;186-197. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Guitton TG, Doornberg JN, Raaymakers EL, Ring D, Kloen P. Fractures of the capitellum and trochlea. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:390-397. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ruchelsman DE, Tejwani NC, Kwon YW, Egol KA. Open reduction and internal fixation of capitellar fractures with headless screws. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91 Suppl 2 Pt 1:38-49. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ring D, Jupiter JB, Gulotta L. Articular fractures of the distal part of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:232-238. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Dubberley JH, Faber KJ, Macdermid JC, Patterson SD, King GJ. Outcome after open reduction and internal fixation of capitellar and trochlear fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:46-54. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 99] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Goodman HJ, Choueka J. Complex coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2005;62:85-89. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Stamatis E, Paxinos O. The treatment and functional outcome of type IV coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus: a retrospective review of five cases. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:279-284. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Mighell M, Virani NA, Shannon R, Echols EL, Badman BL, Keating CJ. Large coronal shear fractures of the capitellum and trochlea treated with headless compression screws. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:38-45. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bryan RSBFM. Fractures of the Distal Humerus. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 1985; 325-333. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | McKee MD, Jupiter JB, Bamberger HB. Coronal shear fractures of the distal end of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:49-54. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Ashwood N, Verma M, Hamlet M, Garlapati A, Fogg Q. Transarticular shear fractures of the distal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:46-52. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sitton SE, Yari SS, Reichel LM. Actual management of elbow fracture dislocations. Minerva Ortop Traumatol. 2013;64:411-424 Available from: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/256108534_Actual_Management_of_Elbow_Fracture_Dislocations. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Sano S, Rokkaku T, Saito S, Tokunaga S, Abe Y, Moriya H. Herbert screw fixation of capitellar fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:307-311. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mighell MA, Harkins D, Klein D, Schneider S, Frankle M. Technique for internal fixation of capitellum and lateral trochlea fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:699-704. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Elkowitz SJ, Polatsch DB, Egol KA, Kummer FJ, Koval KJ. Capitellum fractures: a biomechanical evaluation of three fixation methods. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16:503-506. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Elkowitz SJ, Kubiak EN, Polatsch D, Cooper J, Kummer FJ, Koval KJ. Comparison of two headless screw designs for fixation of capitellum fractures. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2003;61:123-126. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Mehdian H, McKee MD. Fractures of capitellum and trochlea. Orthop Clin North Am. 2000;31:115-127. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Sen MK, Sama N, Helfet DL. Open reduction and internal fixation of coronal fractures of the capitellum. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32:1462-1465. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lee SK, Kim KJ, Park KH, Choy WS. A comparison between orthogonal and parallel plating methods for distal humerus fractures: a prospective randomized trial. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24:1123-1131. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Grantham SA, Norris TR, Bush DC. Isolated fracture of the humeral capitellum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;262-269. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Mancini GB, Fiacca C, Picuti G. Resection of the radial capitellum. Long-term results. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1989;15:295-302. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Kamineni S, Morrey BF. Distal humeral fractures treated with noncustom total elbow replacement. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87 Suppl 1:41-50. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Garcia JA, Mykula R, Stanley D. Complex fractures of the distal humerus in the elderly. The role of total elbow replacement as primary treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:812-816. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | McKee MD, Veillette CJ, Hall JA, Schemitsch EH, Wild LM, McCormack R, Perey B, Goetz T, Zomar M, Moon K. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial of open reduction--internal fixation versus total elbow arthroplasty for displaced intra-articular distal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:3-12. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 238] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Reichel LM, Hillin CD, Reitman CA. Immediate Total Elbow Arthroplasty Following Olecranon Osteotomy: A Case Report. Open J Orthop. 2013;3:213-216. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jost B, Adams RA, Morrey BF. Management of acute distal humeral fractures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A case series. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2197-2205. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Frankle MA, Herscovici D, DiPasquale TG, Vasey MB, Sanders RW. A comparison of open reduction and internal fixation and primary total elbow arthroplasty in the treatment of intraarticular distal humerus fractures in women older than age 65. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:473-480. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Hardy P, Menguy F, Guillot S. Arthroscopic treatment of capitellum fracture of the humerus. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:422-426. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Feldman MD. Arthroscopic excision of type II capitellar fractures. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:743-748. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Kuriyama K, Kawanishi Y, Yamamoto K. Arthroscopic-assisted reduction and percutaneous fixation for coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus: report of two cases. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:1506-1509. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mitani M, Nabeshima Y, Ozaki A, Mori H, Issei N, Fujii H, Fujioka H, Doita M. Arthroscopic reduction and percutaneous cannulated screw fixation of a capitellar fracture of the humerus: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:e6-e9. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Dunning CE, Zarzour ZD, Patterson SD, Johnson JA, King GJ. Muscle forces and pronation stabilize the lateral ligament deficient elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;118-124. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Armstrong AD, Dunning CE, Faber KJ, Duck TR, Johnson JA, King GJ. Rehabilitation of the medial collateral ligament-deficient elbow: an in vitro biomechanical study. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25:1051-1057. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gelinas JJ, Faber KJ, Patterson SD, King GJ. The effectiveness of turnbuckle splinting for elbow contractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:74-78. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Bilsel K, Atalar AC, Erdil M, Elmadag M, Sen C, Demirhan M. Coronal plane fractures of the distal humerus involving the capitellum and trochlea treated with open reduction internal fixation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013;133:797-804. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Mahirogullari M, Kiral A, Solakoglu C, Pehlivan O, Akmaz I, Rodop O. Treatment of fractures of the humeral capitellum using herbert screws. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31:320-325. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | Singh AP, Singh AP, Vaishya R, Jain A, Gulati D. Fractures of capitellum: a review of 14 cases treated by open reduction and internal fixation with Herbert screws. Int Orthop. 2010;34:897-901. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Giannicola G, Sacchetti FM, Greco A, Gregori G, Postacchini F. Open reduction and internal fixation combined with hinged elbow fixator in capitellum and trochlea fractures. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:228-233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ring D. Open reduction and internal fixation of an apparent capitellar fracture using an extended lateral exposure. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:739-744. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Boyd H. Surgical Exposure of the Ulna and Proximal Third of the Radius through One Incision. Surg Gynecol Obs. 1940;71:86-88. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 45. | Kocher T. Operations at the elbow. Textbook of Operative Surgery. 3rd ed. London: Adam and Charles Black 1911; 313-318. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 46. | Kaplan E. Surgical approach to the proximal end of the radius and its use in fractures of the head and neck of the radius. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1941;23:86-92. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | Imatani J, Morito Y, Hashizume H, Inoue H. Internal fixation for coronal shear fracture of the distal end of the humerus by the anterolateral approach. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:554-556. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Malki AA, Salloom FM, Wong-Chung J, Ekri AI. Cannulated screw fixation of fractured capitellum: surgical technique through a limited approach. Injury. 2000;31:204-206. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 49. | Reichel LM, Milam GS, Sitton SE, Curry MC, Mehlhoff TL. Elbow lateral collateral ligament injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38:184-201; quiz 201. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Reichel LM, Milam GS, Reitman CA. Anterior approach for operative fixation of coronoid fractures in complex elbow instability. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2012;16:98-104. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Reichel LM, Morales OA. Gross anatomy of the elbow capsule: a cadaveric study. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38:110-116. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Wright JG, Einhorn TA, Heckman JD. Grades of recommendation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1909-1910. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Brouwer KM, Jupiter JB, Ring D. Nonunion of operatively treated capitellum and trochlear fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:804-807. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |