Published online Oct 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i30.11162

Peer-review started: July 2, 2022

First decision: August 1, 2022

Revised: August 10, 2022

Accepted: September 7, 2022

Article in press: September 7, 2022

Published online: October 26, 2022

Primary intracranial malignant melanoma (PIMM) is rare, and its prognosis is very poor. It is not clear what systematic treatment strategy can achieve long-term survival. This case study attempted to identify the optimal strategy for long-term survival outcomes by reviewing the PIMM patient with the longest survival following comprehensive treatment and by reviewing the related literature.

The patient is a 47-year-old Chinese man who suffered from dizziness and gait disturbance. He underwent surgery for right cerebellum melanoma and was subsequently diagnosed by pathology in June 2000. After the surgery, the patient received three cycles of chemotherapy but relapsed locally within 4 mo. Following the second surgery for total tumor resection, the patient received an injection of Newcastle disease virus-modified tumor vaccine, interferon, and β-elemene treatment. The patient was tumor-free with a normal life for 21 years before the onset of the recurrence of melanoma without any symptoms in July 2021. A third gross-total resection with adjuvant radiotherapy and temozolomide therapy was performed. Brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no residual tumor or recurrence 3 mo after the 3rd operation, and the patient recovered well without neurological dysfunction until the last follow-up in June 2022, which was 22 years following the initial treatment.

It is important for patients with PIMM to receive comprehensive treatment to enable the application of the most appropriate treatment strategies. Long-term survival is not impossible in patients with these malignancies.

Core Tip: Primary intracranial malignant melanoma (PIMM) is quite rare, and its prognosis is poor. Comprehensive treatment, including the surgical resection and the maintenance of postoperative adjuvant treatments by Newcastle disease virus-modified tumor vaccine, interferon, and β-elemene may prolong patient survival. We hope that the PIMM case reported in this paper, which describes a patient whose life was extended by 22 years, can provide useful information for the reference of medical practitioners and patients alike, thereby boosting their confidence in adopting the treatment reported herein.

- Citation: Wong TF, Chen YS, Zhang XH, Hu WM, Zhang XS, Lv YC, Huang DC, Deng ML, Chen ZP. Longest survival with primary intracranial malignant melanoma: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(30): 11162-11171

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i30/11162.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i30.11162

Malignant melanoma (MM) is the most dangerous type of skin cancer. Melanoma accounts for approximately 10% of all patients who develop brain metastases. Approximately one-third of patients with newly diagnosed metastatic melanoma are estimated to have brain metastases[1]. Primary central nervous system (CNS) melanoma accounts for approximately 1% of all melanomas[2,3]. The diagnosis is very challenging. Three criteria have been proposed to diagnose primary CNS melanoma: (1) No melanoma on the skin or eyeball; (2) No surgery history of skin or eyeball melanoma; and (3) No metastatic melanoma in internal organs. Currently, it is believed that the source of primary CNS malignant melanoma may be the melanocytes of the pia mater. From a molecular point of view, the collision of the key structures of these cells leads to focal neurological symptoms, which in turn leads to the formation of malignant melanoma. This disease usually occurs in people under the age of 50, and there is no obvious sex difference. Generally, the disease course is short, and the survival period is usually several months to several years. The survival period is not significantly related to a patient's age. The diagnosis is usually confirmed by pathological biopsy of specimens obtained by surgery. The histopathology has the following characteristics: Tumor cells are of different sizes, most of which are larger than normal cells; the cells are polygonal in shape; the nuclei are round; the nucleoli are obvious; and most of them have obvious nuclear divisions. The cells are consistent with the appearance of malignant melanoma in other parts. In terms of immunohistochemistry, immunohistochemical markers specific to malignant melanoma include HMB45, S100, and SOX10. The positive rate is usually greater than 90%, which is a reliable basis for diagnosis[4]. In terms of treatment, surgical resection is the main treatment for CNS malignant melanoma. Removal of the tumor can prolong survival to a certain extent, but the overall prognosis is very poor. Due to the presence of the blood-brain barrier, chemotherapy usually does not take effect. Radiotherapy can delay tumor recurrence, but it does not significantly help prolong the survival of patients. Therefore, it can be used but with little significance. Immunotherapy is only effective for metastatic malignant melanoma[5]. It has been reported recently that bevacizumab has a certain effect on patients with malignant melanoma brain metastases[6]. However, more treatment methods for primary CNS malignant melanoma still need to be developed.

A 47-year-old man visited our hospital for regular brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) follow-up after surgery to treat primary intracranial malignant melanoma (PIMM) 21 years ago.

All symptoms were denied, and clinical examination findings were negative. The regular brain MRI in July 2021 showed a mixed iso-/hyperdense mass in the right cerebellopontine angle (CPA) measuring 34 mm × 21 mm with a clear margin, so the recurrence of the melanoma was regarded as highly possible again. No melanoma was found on the skin or eyeball. Surgical treatment with gross-total resection (GTR) was arranged on August 12, 2021, which was the third operation.

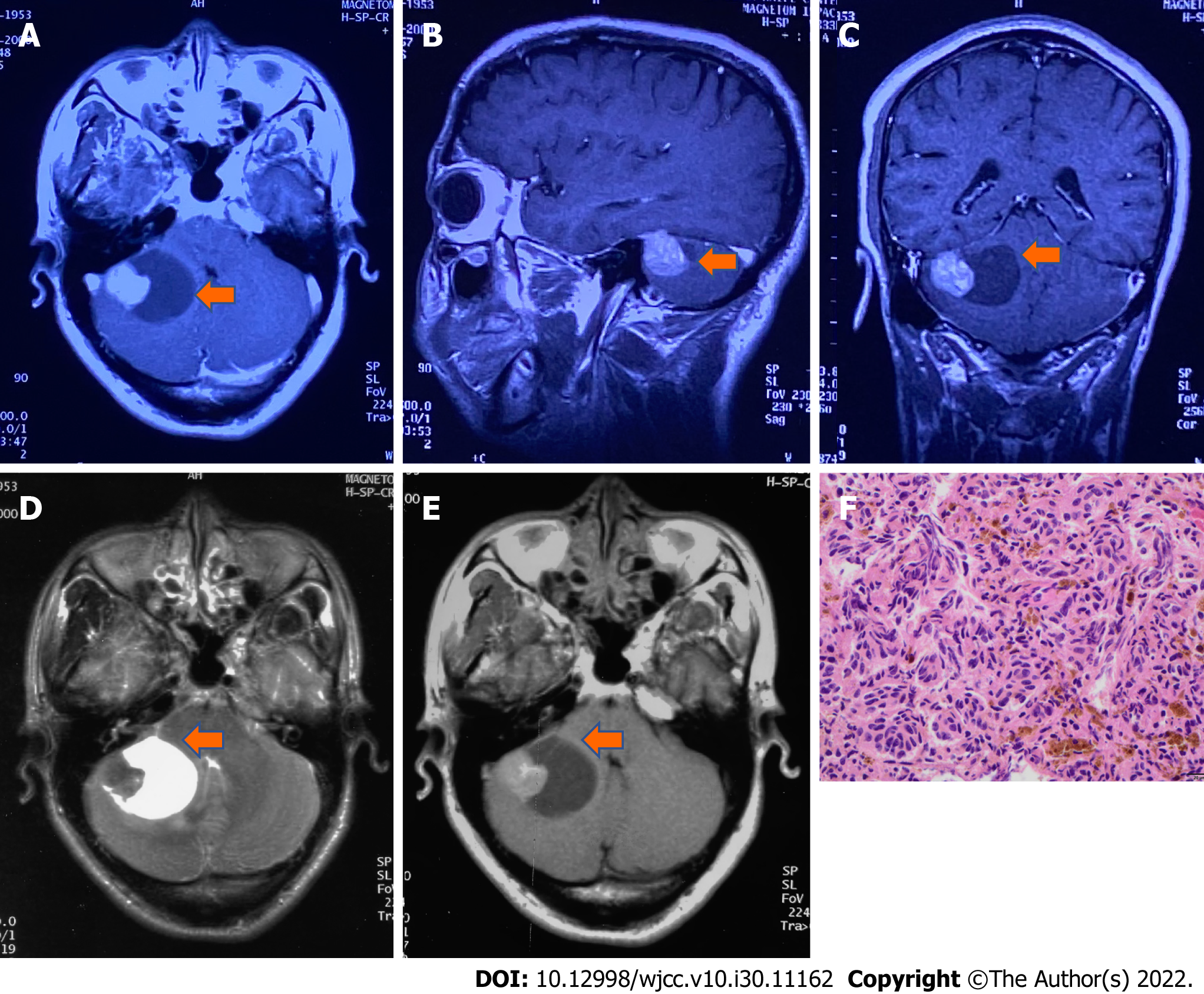

In June 2000, the patient suffered from dizziness and gait disturbance. Brain MRI revealed a lesion in the right cerebellum, and surgical treatment was applied. Melanoma was diagnosed by histopathology examination. The patient received three cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with dacarbazine 400 mg (d1-5), vindesine 4 mg (d1, d5), cisplatin 30 mg (d1-5), and interferon 3 µm subcutaneously 3 times a week. However, the tumor relapsed locally 4 mo after the operation (Figure 1). The patient received a second surgical treatment in October 2000. Histopathology examination revealed melanoma (Figure 1). After the two operations, it was considered that melanoma was not sensitive to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. To prolong his survival period and improve his quality of life, our team used the experimental treatment of Newcastle disease virus (NDV)-modified tumor vaccine through subcutaneous injection twice[6]. Additionally, the patient received interferon (3 µm subcutaneously 2 times a week) and β-elemene (500 mg QD for 14 d each month) for the first 6 mo, followed by maintenance treatment of interferon and β-elemene every 3 to 4 mo, resulting in a total treatment course of 43 mo up to November 2004. He had undergone regular follow-up, and his condition had been healthy, including tumor-free survival during these 21 years.

The patient had no specific personal or family history.

The patient had no neurological symptoms. No melanoma was found on the skin or eyeball.

No specific findings of routine blood tests, blood biochemistry, or immune indices were noted.

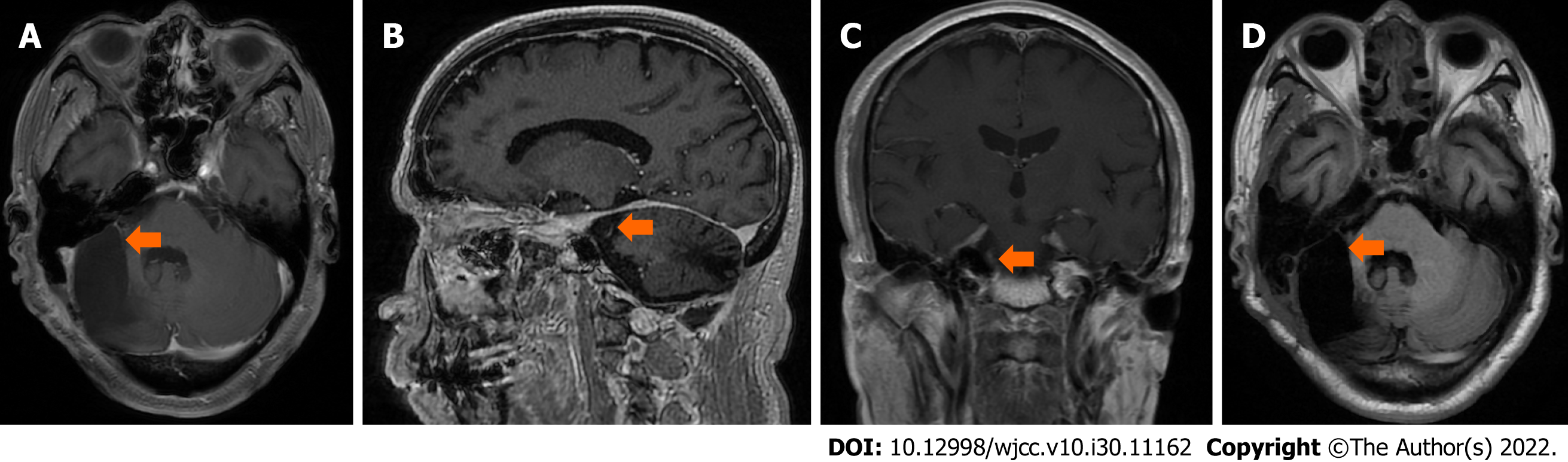

The regular brain MRI in July 2021 showed a mixed iso-/hyperdense mass in the right cerebellopontine angle (CPA) measuring 34 mm × 21 mm with a clear margin (Figure 2), so the recurrence of the melanoma was regarded as highly possible again.

We searched the PIMM in English and Chinese language papers using the search engine of PubMed and Medline-based with keywords of primary intracranial melanoma or primary cerebral melanoma and surgery or radiotherapy or chemotherapy or immunotherapy. All studies published during the period from 1993 to 2021 were collected. Metastases of CNS melanocytic neoplasm and intracranial meningeal melanocytoma were ruled out. In addition, metastatic melanoma without a known primary tumor was also ruled out, as patients who did not undergo workup with positron emission tomography (PET) or whole-body computed tomography (CT) were not enrolled in this study. Sampson et al[1] reported that the overall median survival of patients without treatment for MM was 3 to 4 mo, the 1-year survival rate was 9% to 19%, and only rare patients had prolonged survival. After MM was treated with stereotactic radiosurgery followed by either immunotherapy or targeted therapy, the median overall survival (OS) was 11 mo, and the 1- and 2-year OS rates were 49.5% and 27.4%, respectively, according to Gaudy-Marqueste et al[7], which dramatically improved survival in MM. Baena et al[8] and Arai et al[9] summarized 130 patients with PIMM over the past 30 years. They reported that the mean age of PIMM patients was 45.8 years. No significant sex difference was found. Intracranial hypertension and focal neurologic deficits were commonly observed. The mean OS after gross total resection (> 22 mo) was significantly better than that after surgeries leaving behind residual tumor (12 mo). While there was no significant difference in the survival period between patients with and without adjuvant therapies, leptomeningeal enhancement diagnosed on the initial MRI was the worst prognostic factor. Nakagawa et al[10] reported a patient with PIMM who survived for 9 years and 6 mo after three surgeries to remove the tumor and after receiving adjuvant chemoimmunoradiotherapy in 1989. Önal et al[11] reported a long-term OS of 17 years in a patient who underwent gross total resection of PIMM and received adjuvant chemotherapy with methyl-CCNU in 2006. Li et al[12] established an OS rate of 62.8% at 6 mo and over 5 years at 17.2%, with an estimated median survival time (EMST) of 12 mo. The EMST was better in patients with a solitary-type lesion (13 mo) than in those with a diffuse-type lesion (5 mo). In their review of all patients, those receiving gross total resection with adjuvant radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy had significantly higher 1- and 5-year OS rates, which were 73% and 40.1%, respectively, and a longer EMST (53 mo) than patients who underwent gross total resection alone (20.5 mo) or radiation and/or chemotherapy without resection (13.0 mo). In our case, a 47-year-old male patient was initially diagnosed with PIMM and survived for 22 years after comprehensive treatment, including surgical removal of the tumor three times, adjuvant chemoimmunoradiotherapy, and β-elemene, an extract from the natural plant turmeric with antitumor activity. This is the longest OS case ever reported in the English and Chinese literature according to a search of the PubMed and MEDLINE databases.

Not applicable.

The patient was diagnosed with recurrent right CPA PIMM.

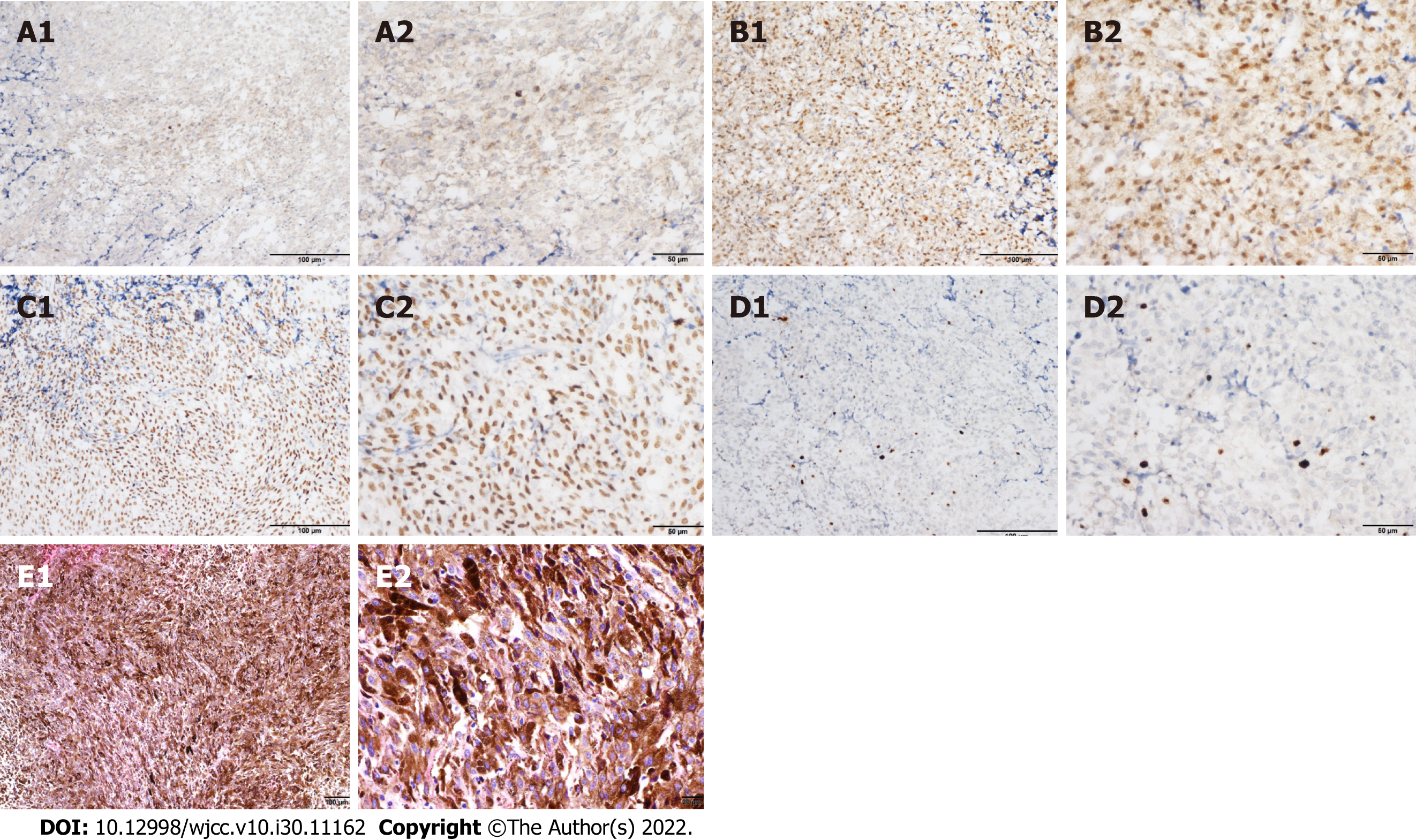

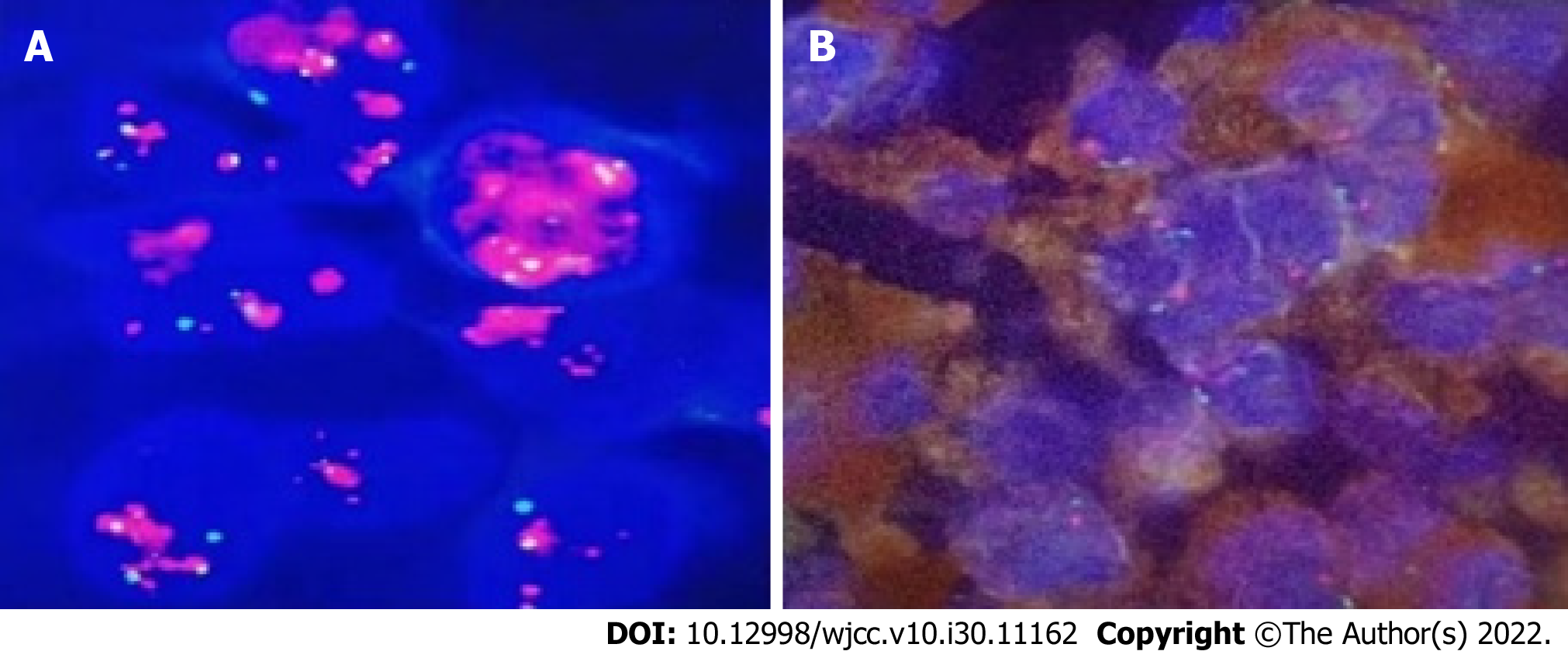

During the third operation, it was observed that the tentorial margin had obviously turned black, and a dark black mass was seen under the petrosal vein. The tumor was solid, soft, tender, black, and rich blood supplied to attach to the dura mater, sparing the parenchyma of the cortex. The facial nerve was pushed outward and upward, and the trochlear and trigeminal nerves were pressed forward and downward. The tumor had a complete and smooth capsule, with a dark coal-like appearance and a black sesame paste-like content (Figure 3). The histopathology examination revealed melanoma (Figures 4A-C) positive for HMB45, Melan A, S-100, SOX-10, and p16. The Ki-67 index was 8% (+) (Figure 4D). Chromosomal locations of positive genes were detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in MM: RREB1-6p25/6p11.1-q11.1 (Figure 6 and Table 1). Further examinations included CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvic region as well as PET scans of the whole brain and body, which were all negative. The patient was discharged from the hospital 10 d after GTR with no complications and went on for adjuvant radiotherapy (IMRT, GTV 45 Gy/9 f, CTV 27 Gy/9 f) and chemotherapy with temozolomide as a 5-d oral schedule every 4 wk (administered at 150 mg/m2/d for the first cycle, then 200 mg/m2/d for forward cycles).

| Gene | Chromosomal location | Result |

| CCND1 signal count/count nuclei | 6q23 | Negative |

| MYB signal count/count nuclei | 6q25 | Negative |

| RREB1 abnormal cell count/counted cells | 6p25/6p11.1-q11.1 | Positive |

| MYB missing cells/counted cells | 6p23/6p11.1-q11.1 | Negative |

Brain MRI showed that no residual tumor or recurrence was found in the right CPA 3 mo after the 3rd operation (Figure 5). Up to the last follow-up on June 17, 2022, the patient recovered well with no recurrence or related sequelae. His condition was fine without neurological dysfunction, and he resumed his normal life.

The incidence is 0.005/100000 for melanoma. There is a slight female predisposition, with a female-to-male ratio of 1.5:1. The age range of patients with primary nodular melanoma is 15 to 71 years, averaging 43 years. Intracranial melanoma is classified as primary or metastatic, and PIMM accounts for 1% of all melanomas[13]. Primary melanoma derives from leptomeningeal melanocytes. Pedersen et al[14] established the first model of melanoma driven by the oncogenic NRAS gene and reported two cases of children with melanoma of the CNS that presented mutations in the NRAS gene. The CNS melanoma is associated with mutations in the GNAQ and GNA11 genes; however, mutations in the NRAS gene are rare in adults[15].

The symptoms and signs are secondary to either the local effects on the CNS parenchyma or hydrocephalus. The rapid progression with increasing intracranial pressure may suggest malignant transformation, which results in irritability, vomiting, lethargy, seizures, and so on. The diagnosis of melanocytic lesions relies on histopathological examination. Most benign and malignant melanocytic lesions display melanin pigment distributed within tumor cells, tumor stroma, and the cytoplasm of tumoral macrophages. Rare melanocytomas and fortuitous primary melanomas do not show melanin pigment, consistent with amelanotic melanoma. Histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations are highly sensitive for amelanotic melanoma.

Isiklar et al[16] classified the MRI manifestations into four groups: (1) The melanotic group, with hyperintensity on T1 and hypointensity on T2; (2) The amelanotic group, with iso-/hypointensity on T1 and iso-/hyperintensity on T2; (3) The mixed group, suiting neither of the two criteria; and (4) The hemorrhagic group, with characteristics of intra/peritumoral hemorrhage. There are hematopoietic neoplasms, cystic changes, and necrosis. One of them was suspected to be amelanotic melanoma. In our present case, T1-weighted hyperintense and T2-weighted isointensity signals consistent with the melanotic group were noted (Figure 3). The immunohistochemical analysis showed positive staining for HMB-45, S100, and vimentin. These results are important in the differential diagnosis of melanoma, particularly the positive staining for HMB-45 which is a specific biomarker for melanoma. Actually, the case in the present study also echoes such findings. These new findings reveal that RREB1 functions as both a transcriptional repressor and transcriptional activator for the transcriptional regulation of target genes. RREB1 is believed to function as a diagnostic biomarker or new drug target for melanoma detection.

Three criteria have been proposed to diagnose primary CNS melanoma: (1) The skin or eyeballs are negative for melanoma; (2) The skin or eyeballs have no history of melanoma resection; and (3) The internal organs are negative for melanoma metastasis. Our presented case had histopathology confirmed MM in the CPA. Whole-body examination ruled out the existence of melanoma outside of the CNS.

MM, which is highly aggressive and chemoradioresistant, has a poor prognosis and easily metastasizes. The prognosis of PIMM lesions appears to be better than that of metastatic examples. It is clear that total resection of tumors should be the key point for treatment[9,10]. For our case of PIMM, gross total resection was achieved; furthermore, excessive removal of invaded adjacent meninges in the 2nd surgery could be one of the important factors resulting in his long-term survival. Immunotherapy has developed rapidly for MM treatment[17]. The prognosis for patients with melanoma brain metastasis (MBM) has also improved, coinciding with the approval of PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors and combined BRAF/MEK targeting therapy[18]. However, controversy remains for MM in the CNS; at least, there is little clinical evidence showing efficacy for PIMM[19]. With respect to the experience of our case, the patient survived for more than 21 years after the comprehensive treatment. Although this patient suffered a relapse after the first surgery, he continued to survive in the following 21 years or more after the second surgery in conjunction with ensuing adjuvant treatment. It remains questionable which of the following could yield effects apart from surgery: Radiotherapy, chemo

PIMM is quite rare, and its prognosis is poor. However, comprehensive treatment, including surgical resection followed by appropriate adjuvant treatment strategies, may prolong patient survival. We hope that the PIMM case reported in this paper, which describes a patient whose life was extended by 22 years, can provide useful information for the reference of medical practitioners and patients alike, thereby boosting their confidence in adopting the treatment reported therein.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: He R, China; Jabbarpour Z, Iran S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Sampson JH, Carter JH Jr, Friedman AH, Seigler HF. Demographics, prognosis, and therapy in 702 patients with brain metastases from malignant melanoma. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:11-20. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 374] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Puyana C, Denyer S, Burch T, Bhimani AD, McGuire LS, Patel AS, Mehta AI. Primary Malignant Melanoma of the Brain: A Population-Based Study. World Neurosurg. 2019;130:e1091-e1097. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Davies MA, Liu P, McIntyre S, Kim KB, Papadopoulos N, Hwu WJ, Hwu P, Bedikian A. Prognostic factors for survival in melanoma patients with brain metastases. Cancer. 2011;117:1687-1696. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 367] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bastian BC. The molecular pathology of melanoma: an integrated taxonomy of melanocytic neoplasia. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:239-271. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 306] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Glitza IC, Smalley KSM, Brastianos PK, Davies MA, McCutcheon I, Liu JKC, Ahmed KA, Arrington JA, Evernden BR, Smalley I, Eroglu Z, Khushalani N, Margolin K, Kluger H, Atkins MB, Tawbi H, Boire A, Forsyth P. Leptomeningeal disease in melanoma patients: An update to treatment, challenges, and future directions. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2020;33:527-541. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Simonsen TG, Gaustad JV, Rofstad EK. Bevacizumab treatment of meningeal melanoma metastases. J Transl Med. 2020;18:13. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gaudy-Marqueste C, Dussouil AS, Carron R, Troin L, Malissen N, Loundou A, Monestier S, Mallet S, Richard MA, Régis JM, Grob JJ. Survival of melanoma patients treated with targeted therapy and immunotherapy after systematic upfront control of brain metastases by radiosurgery. Eur J Cancer. 2017;84:44-54. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rodriguez y Baena R, Gaetani P, Danova M, Bosi F, Zappoli F. Primary solitary intracranial melanoma: case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:26-37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Arai N, Kagami H, Mine Y, Ishii T, Inaba M. Primary Solitary Intracranial Malignant Melanoma: A Systematic Review of Literature. World Neurosurg. 2018;117:386-393. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nakagawa H, Hayakawa T, Niiyama K, Nii Y, Yoshimine T, Mori S. Long-term survival after removal of primary intracranial malignant melanoma. Case report. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1989;101:84-88. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Önal C, Ozyigit G, Akyürek S, Selek U, Ozyar E, Atahan IL. Primary intracranial solitary melanoma: A rare case with long survival. Turk J Cancer. 2006;36:185-187. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Li CB, Song LR, Li D, Weng JC, Zhang LW, Zhang JT, Wu Z. Primary intracranial malignant melanoma: proposed treatment protocol and overall survival in a single-institution series of 15 cases combined with 100 cases from the literature. J Neurosurg. 2019;132:902-913. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shah I, Imran M, Akram R, Rafat S, Zia K, Emaduddin M. Primary intracranial malignant melanoma. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:157-159. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pedersen M, Küsters-Vandevelde HVN, Viros A, Groenen PJTA, Sanchez-Laorden B, Gilhuis JH, van Engen-van Grunsven IA, Renier W, Schieving J, Niculescu-Duvaz I, Springer CJ, Küsters B, Wesseling P, Blokx WAM, Marais R. Primary melanoma of the CNS in children is driven by congenital expression of oncogenic NRAS in melanocytes. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:458-469. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Murali R, Wiesner T, Rosenblum MK, Bastian BC. GNAQ and GNA11 mutations in melanocytomas of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:457-459. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Meacham RB, Townsend RR, Drose JA. Ejaculatory duct obstruction: diagnosis and treatment with transrectal sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1463-1466. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 127] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Luke JJ, Flaherty KT, Ribas A, Long GV. Targeted agents and immunotherapies: optimizing outcomes in melanoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:463-482. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 692] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 806] [Article Influence: 115.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bander ED, Yuan M, Carnevale JA, Reiner AS, Panageas KS, Postow MA, Tabar V, Moss NS. Melanoma brain metastasis presentation, treatment, and outcomes in the age of targeted and immunotherapies. Cancer. 2021;127:2062-2073. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Misir Krpan A, Rakusic Z, Herceg D. Primary leptomeningeal melanomatosis successfully treated with PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e22928. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Batliwalla FM, Bateman BA, Serrano D, Murray D, Macphail S, Maino VC, Ansel JC, Gregersen PK, Armstrong CA. A 15-year follow-up of AJCC stage III malignant melanoma patients treated postsurgically with Newcastle disease virus (NDV) oncolysate and determination of alterations in the CD8 T cell repertoire. Mol Med. 1998;4:783-794. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sinkovics J, Horvath J. New developments in the virus therapy of cancer: a historical review. Intervirology. 1993;36:193-214. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Takamura-Ishii M, Miura T, Nakaya T, Hagiwara K. Induction of antitumor response to fibrosarcoma by Newcastle disease virus-infected tumor vaccine. Med Oncol. 2017;34:171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhang X, Chen Y, Yao J, Zhang Y, Li M, Yu B, Wang K. β-elemene combined with temozolomide in treatment of brain glioma. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2021;28:101144. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhai B, Zhang N, Han X, Li Q, Zhang M, Chen X, Li G, Zhang R, Chen P, Wang W, Li C, Xiang Y, Liu S, Duan T, Lou J, Xie T, Sui X. Molecular targets of β-elemene, a herbal extract used in traditional Chinese medicine, and its potential role in cancer therapy: A review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;114:108812. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 128] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yu X, Xu M, Li N, Li Z, Li H, Shao S, Zou K, Zou L. β-elemene inhibits tumor-promoting effect of M2 macrophages in lung cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;490:514-520. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |