Published online Oct 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i30.11059

Peer-review started: June 24, 2022

First decision: August 7, 2022

Revised: August 20, 2022

Accepted: September 12, 2022

Article in press: September 12, 2022

Published online: October 26, 2022

Paragangliomas may be preoperatively misdiagnosed as non-functioning retroperitoneal tumors and are sometimes suspected only at the time of intraoperative manipulation. Without preoperative alpha blockade preparation, a hypertensive crisis during tumor manipulation and hypotension after tumor removal may result in critical consequences. Therefore, primary consideration should be given to the continuation or discontinuation of surgery on the basis of the possibility of gentle surgical manipulation and hemodynamic stabilization. We report two cases of paragangliomas detected intraoperatively.

A 65-year-woman underwent laparoscopic small-bowel wedge resection. A hypertensive crisis occurred during manipulation of the mass, and an unre

When an undiagnosed paraganglioma is suspected intraoperatively, reoperation after adequate preparation should be considered as an option to avoid fatal outcomes.

Core Tip: Undiagnosed paragangliomas may be suspected at the time of intraoperative manipulation. Tumor removal without preoperative alpha blockade preparation can lead to serious hemodynamic instability. The present case report describes different intraoperative decisions for two patients with undiagnosed paragangliomas. Intraoperative cancellation of surgery may not always be feasible or practical, but it should be considered as an option in cases requiring frequent manipulation of the tumor.

- Citation: Kang D, Kim BE, Hong M, Kim J, Jeong S, Lee S. Different intraoperative decisions for undiagnosed paraganglioma: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(30): 11059-11065

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i30/11059.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i30.11059

Paragangliomas are rare neuroendocrine tumors derived from extra-adrenal chromaffin cells, which are catecholamine-producing postganglionic sympathetic neurons[1-3]. Similar to pheochromocytomas, these tumors can show life-threatening complications such as hypertensive crisis and hemodynamic instability during surgery. To reduce these complications, preoperative preparation with an adrenal blockade is essential. However, paragangliomas may be preoperatively misdiagnosed as non-functioning retroperitoneal tumors since patients have no specific preoperative symptoms, such as palpitation. In these patients, paragangliomas may be suspected at the time of intraoperative manipulation.

Previous reports of undiagnosed catecholamine-producing tumors have described successful operations with careful surgical resection and intensive anesthetic management[4-6]. However, most cases involved a hypertensive crisis, which was followed by severe postoperative hypotension. The patients may even show intraoperative acute catecholamine cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac arrest[7]. Adequate preparation may prevent these lethal situations. Therefore, when a catecholamine-producing paraganglioma is suspected during surgery, primary consideration should be given to the continuation or discontinuation of surgery. Surgeons and anesthesiologists should discuss the possibility of gentle surgical manipulation, intraoperative hemodynamic stabilization, and postoperative complications.

We report two cases of intraoperatively detected paragangliomas.

Case 1: A 65-year-woman was admitted for laparoscopic small-bowel wedge resection of a 6-cm-sized mass suspected to be a small-bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). During laparoscopic manipulation of the mass, systolic blood pressure suddenly increased to 250-280 mmHg.

Case 2: A 54-year-man was admitted for open resection of a 3-cm-sized retroperitoneal mass suspected to be leiomyosarcoma. During careful dissection of the mass superior to the right adrenal gland, systolic blood pressure and pulse rate increased to 200-230 mmHg and 130-150 bpm, respectively.

Case 1: The patient’s blood pressure was 178/85 mmHg, and her heart rate was 65 bpm on arrival to the operating room. General anesthesia was induced and maintained with propofol and remifentanil. The mass became visible 20 min after the start of laparoscopic surgery. When the surgeon manipulated the mass, systolic blood pressure increased to 250-300 mmHg. Repeated doses of nicardipine (1-mg doses with a total dose of 3 mg) were administered, and the systolic blood pressure decreased to 120 mmHg. Within 5 min, the blood pressure increased again, and the patient showed tachycardia (110-130 bpm). Nicardipine and esmolol were then administered repeatedly, and the anesthetic depth was increased by increasing the doses of propofol and remifentanil. However, adequate control of blood pressure could not be achieved.

Case 2: The patient’s blood pressure and heart rate on arrival to the operating room were 136/82 mmHg and 79 bpm, respectively. General anesthesia was maintained with desflurane and remifentanil after anesthesia induction with propofol. The mass became visible 35 min after the start of the operation. When the surgeon manipulated the mass, the systolic blood pressure suddenly increased to 185 mmHg. After administration of nicardipine (0.5 mg), the blood pressure normalized. Anesthetic depth was also increased by increasing the doses of desflurane and remifentanil. However, systolic blood pressure and pulse rate increased to 200-230 mmHg and 130-150 bpm, respectively, during careful dissection of the mass superior to the right adrenal gland. The blood pressure and heart rate were not adequately controlled by administering multiple doses of nicardipine and esmolol.

Case 1: The patient had been receiving an angiotensin-2 receptor blocker and thiazide for the treatment of hypertension from 2016. Her blood pressure was well controlled until the morning of the surgery. She had been in a euthyroid state with levothyroxine medication after undergoing total thyroidectomy in 2006.

Case 2: The patient was receiving clopidogrel owing to a history of deep vein thrombosis. Clopidogrel was withheld for 5 d before surgery. The patient had no history of hypertension.

None of the two patients had any relevant personal or family history.

Cases 1 and 2: The results of preoperative physical examination were unremarkable. During general anesthesia, the depth of anesthesia and arterial blood pressure were continuously monitored. No prominent elevation of blood pressure or heart rate was observed during tracheal intubation, skin incision, or laparoscopic port insertion. Deep neuromuscular blockade was maintained with continuous infusion of rocuronium under neuromuscular monitoring.

The results of preoperative laboratory tests and electrocardiography were normal.

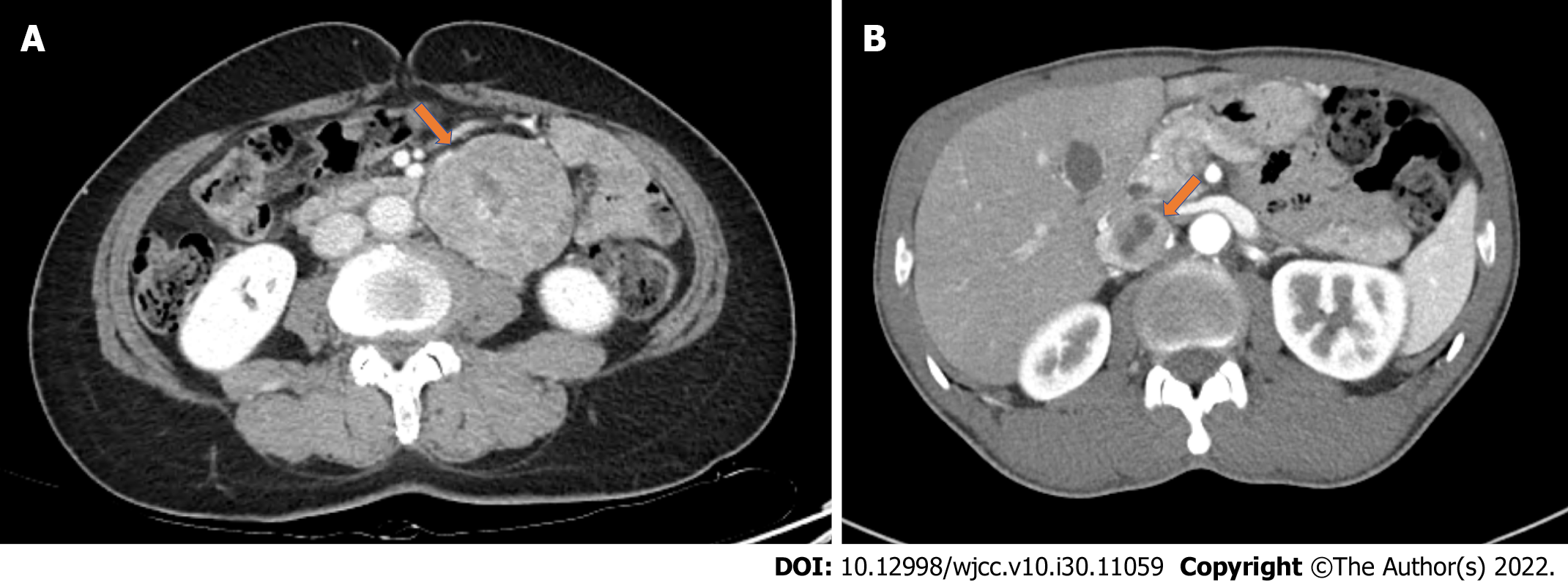

Case 1: Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed an approximately 6-cm-sized well-circumscribed heterogeneously enhancing mass around the duodenal flexure (Figure 1A). The initial radiographic impression was a GIST.

Case 2: Abdominal CT showed an approximately 3-cm-sized heterogeneously enhancing mass in the retrocaval space (Figure 1B). The mass pushed the inferior vena cava forward and abutted the liver in the lateral portion. The initial radiographic impression was a leiomyosarcoma with possible invasion of the liver.

An unrecognized catecholamine-producing paraganglioma was highly suspected based on the high blood pressure and heart rate induced by intraoperative manipulation of the mass.

The surgeon was asked to stop the manipulation of the tumor to prevent further hypertensive crises. Surgical procedures involving undiagnosed paragangliomas without adequate preoperative preparation may lead to increased morbidity and mortality. Therefore, the surgeon and anesthesiologists discussed whether to proceed with the surgical procedure or cancel it.

The surgeon thought that tumor excision could be performed with minimal manipulation of the tumor because the tumor seemed to have a relatively clear margin without invasion to the surrounding tissue. The anesthesiologists then agreed to resume the surgical procedure and prepare cardiovascular drugs for intensive hemodynamic control. For quick and safe excision, the laparoscopic procedure was converted to open surgery in accordance with the surgeon’s decision.

During tumor excision, esmolol and nicardipine were continuously infused with intermittent bolus injections to minimize severe hypertension and tachycardia. The mass was completely removed 70 min after the start of surgery. Following mass removal, systolic blood pressure decreased to 75 mmHg. Aggressive fluid resuscitation was performed with continuous administration of dopamine and norepinephrine until the patient was hemodynamically stable.

Continuous manipulation of the mass seemed inevitable due to adhesion between the right adrenal gland and the mass in a narrow surgical field. The possibility of the inferior vena cava invasion and massive bleeding also could not be ruled out. The surgeon and anesthesiologists decided to cancel the surgical procedure and planned to perform a reoperation after adequate preparation a few weeks later.

An endocrinologist in the general ward evaluated the patient. The results of 24-h urinary metanephrine and catecholamine (metanephrine 2700 µg/d, norepinephrine 133.8 µg/d, and epinephrine 79.2 µg/d) strongly suggested the presence of a catecholamine-producing paraganglioma. We decided to proceed with reoperation after an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist (doxazosin mesylate) regimen for two weeks.

The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) after surgery for close monitoring of vital signs. All vasopressors were stopped 7 h after ICU admission. She was transferred to the general ward on postoperative day (POD) 2 and discharged without any complications on POD 4. The mass was histopathologically confirmed as an extra-adrenal paraganglioma.

The patient returned to the operating room after alpha blockade therapy for two weeks. Anesthesia induction was uneventful. During tumor manipulation, the increase in blood pressure was easily controlled with small doses of nicardipine. Modest hypotension (85/40 mmHg) occurred after tumor excision and was treated with short-term infusion of norepinephrine and fluids. The patient was transferred to the ICU after surgery and was hemodynamically stable without any vasopressors. He was transferred to the general ward on POD 1 and discharged without any complications on POD 12. The mass was histopathologically confirmed to be an extra-adrenal paraganglioma.

The present case report describes different intraoperative decisions for two patients with undiagnosed paragangliomas. We aimed to clarify the decision-making regarding continuation of surgery when a paraganglioma was identified intraoperatively. This issue has not been emphasized in previous literatures.

Patients with paragangliomas do not always show catecholamine-related symptoms, making proper preoperative diagnosis difficult. The incidence of headache, palpitations, perspiration, pallor, and hypertension has been reported to be 26%, 21%, 25%, 12%, and 64%, respectively[8]. Although the first patient had hypertension, her preoperative blood pressure was well-controlled. The second patient had no history of hypertension and did not show any symptoms associated with catecholamine-secreting tumors. Therefore, the possibility of paraganglioma was overlooked and hormonal studies were not conducted in either case.

When an adrenal or retroperitoneal mass without clinical symptom is incidentally detected, results of imaging studies may sometimes indicate the need for biochemical screening for catecholamine-producing tumors. Therefore, previous images should be interpreted with caution, taking into consideration of additional imaging studies. For example, degree of attenuation on unenhanced CT images[9,10] or signal intensity on T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images[11,12] of the mass could provide presumptive criteria to characterize production of catecholamine. Functional imaging such as scintigraphy with metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) or positron-emission tomography (PET) scanning is also effective in localizing metastatic disease or multiple paragangliomas[13-15].

Elective surgery in patients with undiagnosed paragangliomas or pheochromocytomas can be life-threatening. Previous studies have reported the occurrence of a hypertensive crisis primarily during tumor manipulation and/or induction of anesthesia. The complications arising from alarmingly high blood pressure include cerebrovascular hemorrhage, hypertensive encephalopathy, neurological deficits, severe arterial spasms causing unconsciousness, metabolic acidemia, heart failure, arrhythmias, and myocardial infarction[16]. Severe hypotension after tumor removal, rather than hypertension during tumor manipulation, can lead to even more disastrous consequences, including cardiac arrest and death. In the cases described in this report, serious complications related to hypotension did not occur. However, severe hypotension developed after tumor removal in the first patient (case 1), who was not treated preoperatively. Conversely, modest and transient hypotension was observed after tumor removal in the second patient (case 2), who was treated with doxazosin. This finding emphasizes the importance of appropriate preoperative preparation in patients with suspected catecholamine-producing tumors.

The clinical practice guidelines for pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma issued by the Endocrine Society continue to recommend alpha-adrenergic blockade for at least 7 d preoperatively to prevent unpredictable instability in blood pressure during surgery[12]. Although the concept of adrenergic blockade-free management is evolving[17,18], there is no consensus supporting this approach[15]. High levels of catecholamines in patients with paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma produce chronic vasoconstriction and a subsequent decrease in blood volume. Therefore, in combination with the use of alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers, preoperative fluid replacement is essential for gradual restoration of catecholamine-induced blood volume contraction[12] and can reduce the risk of severe and sustained hypotension after tumor removal[19].

Paragangliomas are frequently found in areas that are difficult to resect, as observed in the second patient. Although intraoperative cancellation of the surgery was not an easy decision, the surgeon and anesthesiologists believed that continuous manipulation of the tumor without adequate preparation might result in disastrous consequences. Fortunately, the mass in the first patient was in a favorable location, and serious hemodynamic instability could be avoided by minimal manipulation under aggressive use of vasoactive drugs.

Hemodynamic management of patients with catecholamine-producing tumors remains a challenge for anesthesiologists, especially when preoperative alpha blockade has not been established. When an undiagnosed paraganglioma or pheochromocytoma is suspected during surgery, immediate and coordinated responses by surgeons and anesthesiologists are required to avoid fatal outcomes. Intraoperative cancellation of surgery may not always be feasible or practical, but it should be considered as an option in cases requiring frequent manipulation of the tumor.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Maurea S, Italy; Moshref RH, Saudi Arabia S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Joynt KE, Moslehi JJ, Baughman KL. Paragangliomas: etiology, presentation, and management. Cardiol Rev. 2009;17:159-164. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Renard J, Clerici T, Licker M, Triponez F. Pheochromocytoma and abdominal paraganglioma. J Visc Surg. 2011;148:e409-e416. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lee JA, Duh QY. Sporadic paraganglioma. World J Surg. 2008;32:683-687. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fox WC, Read M, Moon RE, Moretti EW, Colin BJ. An Undiagnosed Paraganglioma in a 58-Year-Old Female Who Underwent Tumor Resection. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2017;2017:5796409. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Han IS, Kim YS, Yoo JH, Lim SS, Kim TK. Anesthetic management of a patient with undiagnosed paraganglioma -a case report-. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;65:574-577. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mahmoud S, Salami M, Salman H. A rare serious case of retroperitoneal paraganglioma misdiagnosed as duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a case report. BMC Surg. 2020;20:49. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen X, Liu X, Tian S, Wang X, Tang H, Yu Y, Zhang D, Peng Y. Cardiac arrest and catecholamine cardiomyopathy secondary to a misdiagnosed ectopic pheochromocytoma. Endokrynol Pol. 2020;71:479-480. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Erickson D, Kudva YC, Ebersold MJ, Thompson GB, Grant CS, van Heerden JA, Young WF Jr. Benign paragangliomas: clinical presentation and treatment outcomes in 236 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5210-5216. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 287] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Canu L, Van Hemert JAW, Kerstens MN, Hartman RP, Khanna A, Kraljevic I, Kastelan D, Badiu C, Ambroziak U, Tabarin A, Haissaguerre M, Buitenwerf E, Visser A, Mannelli M, Arlt W, Chortis V, Bourdeau I, Gagnon N, Buchy M, Borson-Chazot F, Deutschbein T, Fassnacht M, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Motyka M, Rzepka E, Casey RT, Challis BG, Quinkler M, Vroonen L, Spyroglou A, Beuschlein F, Lamas C, Young WF, Bancos I, Timmers HJLM. CT Characteristics of Pheochromocytoma: Relevance for the Evaluation of Adrenal Incidentaloma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:312-318. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dinnes J, Bancos I, Ferrante di Ruffano L, Chortis V, Davenport C, Bayliss S, Sahdev A, Guest P, Fassnacht M, Deeks JJ, Arlt W. MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Imaging for the diagnosis of malignancy in incidentally discovered adrenal masses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;175:R51-R64. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Maurea S, Caracò C, Klain M, Mainolfi C, Salvatore M. Imaging characterization of non-hypersecreting adrenal masses. Comparison between MR and radionuclide techniques. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;48:188-197. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Grebe SK, Murad MH, Naruse M, Pacak K, Young WF Jr; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1915-1942. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1592] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1521] [Article Influence: 152.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Maurea S, Cuocolo A, Reynolds JC, Neumann RD, Salvatore M. Diagnostic imaging in patients with paragangliomas. Computed tomography, magnetic resonance and MIBG scintigraphy comparison. Q J Nucl Med. 1996;40:365-371. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Lastoria S, Maurea S, Vergara E, Acampa W, Varrella P, Klain M, Muto P, Bernardy JD, Salvatore M. Comparison of labeled MIBG and somatostatin analogs in imaging neuroendocrine tumors. Q J Nucl Med. 1995;39:145-149. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:552-565. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 305] [Article Influence: 61.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Livingstone M, Duttchen K, Thompson J, Sunderani Z, Hawboldt G, Sarah Rose M, Pasieka J. Hemodynamic Stability During Pheochromocytoma Resection: Lessons Learned Over the Last Two Decades. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:4175-4180. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Groeben H, Nottebaum BJ, Alesina PF, Traut A, Neumann HP, Walz MK. Perioperative α-receptor blockade in phaeochromocytoma surgery: an observational case series. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118:182-189. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shao Y, Chen R, Shen ZJ, Teng Y, Huang P, Rui WB, Xie X, Zhou WL. Preoperative alpha blockade for normotensive pheochromocytoma: is it necessary? J Hypertens. 2011;29:2429-2432. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pacak K. Preoperative management of the pheochromocytoma patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4069-4079. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 307] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |