Published online Aug 31, 2023. doi: 10.5528/wjtm.v11.i1.1

Peer-review started: April 23, 2023

First decision: June 19, 2023

Revised: July 5, 2023

Accepted: August 17, 2023

Article in press: August 17, 2023

Published online: August 31, 2023

Processing time: 129 Days and 16.5 Hours

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms arising from neuroendocrine cells, which contribute a small fraction of gastro

We present case reports of 5 patients obtained over a period of 10 years in our center with dNETs. One patient had moderately differentiated NET and the remaining four had well-differentiated NET. Surveillance endoscopy was recom

Recently, the number of reported cases of NETs has increased due to advance

Core Tip: Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms arising from neuroendocrine cells. Non-functional NETs are mostly asymptomatic and need a high degree of clinical suspicion. Duodenal NETs represent nearly 2% of all Gastroenteropancreatic neoplasms, most of which are sporadic and non-functional. The average age of presentation is 60 years with a slight male preponderance. NETs are categorized by the World Health Organization classification, and radical surgery is the only curative therapy. Endoscopic therapy is especially validated for sub-centimetric lesions and surgical intervention is recommended for lesions above 2 cm, sporadic gastrinoma, periampullary location, and poorly differentiated d-NET.

- Citation: Malladi UD, Chimata SK, Bhashyakarla RK, Lingampally SR, Venkannagari VR, Mohammed ZA, Vargiya RV. Duodenal neuroendocrine tumor-tertiary care centre experience: A case report. World J Transl Med 2023; 11(1): 1-8

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6132/full/v11/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5528/wjtm.v11.i1.1

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms arising from neuroendocrine cells. They are heterogeneous in terms of clinical symptoms, location, and prognosis. Non-functional NETs are mostly asymptomatic and need a high degree of clinical suspicion. Duodenal NETs (dNETs) represent nearly 2% of all gastroenteropancreatic neoplasms, most of which are sporadic and non-functional. D-NETs are having slight male predominance, with the average age at diagnosis being 60 years. They are often small-sized lesions, with the most common functional d-NET being gastrinoma followed by somatostatinoma. NETs are categorized by the World Health Organization classification, and radical surgery is the only curative therapy. Endoscopic therapy is especially validated for sub-centimetric lesions and surgical intervention is recommended for lesions above 2 cm, sporadic gastrinoma, periampullary location, and poorly differentiated d-NET. Other therapeutic options are cytotoxic chemotherapy, somatostatin analogs, interferon alpha, and peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) apart from symptomatic therapy[1].

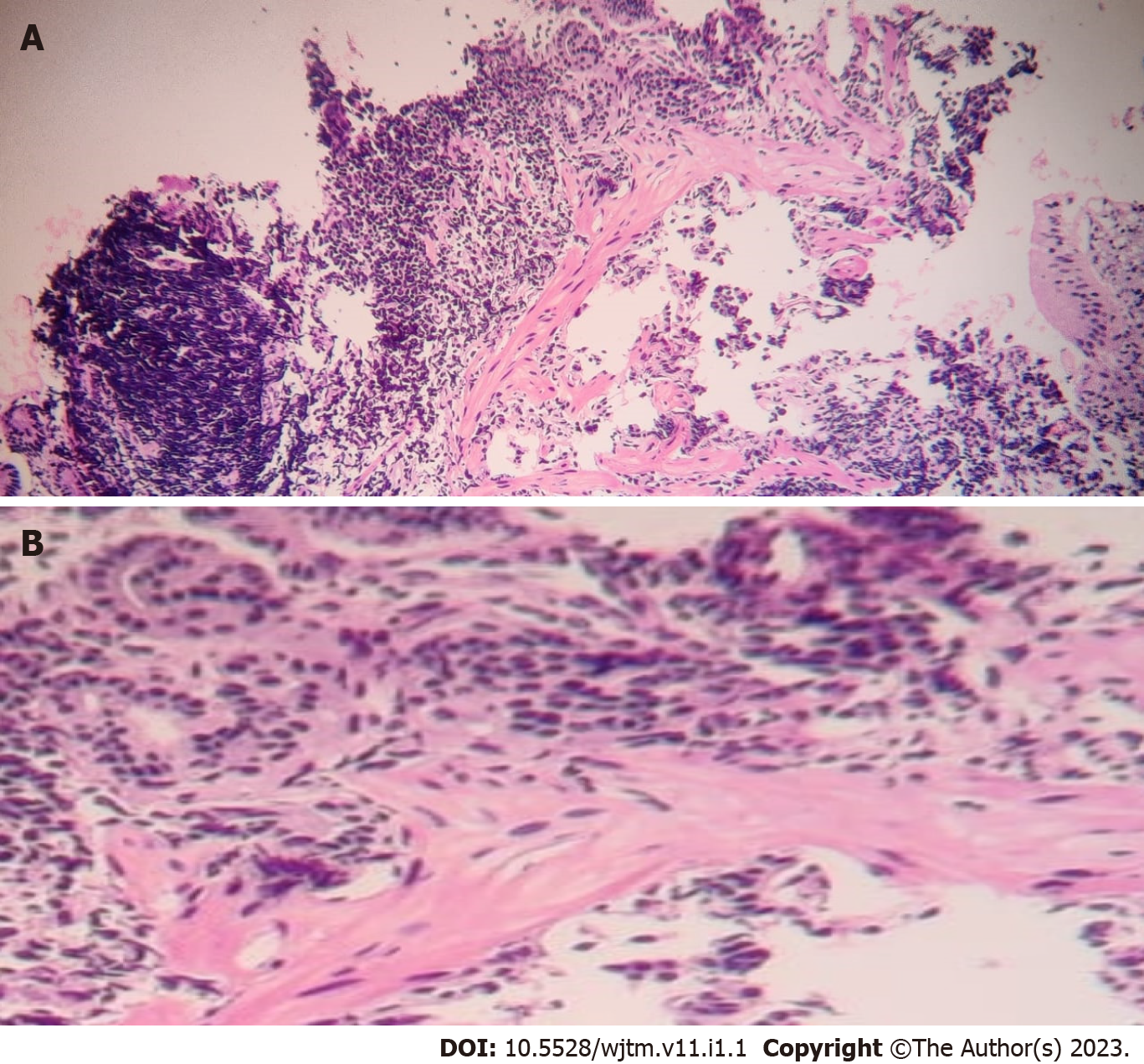

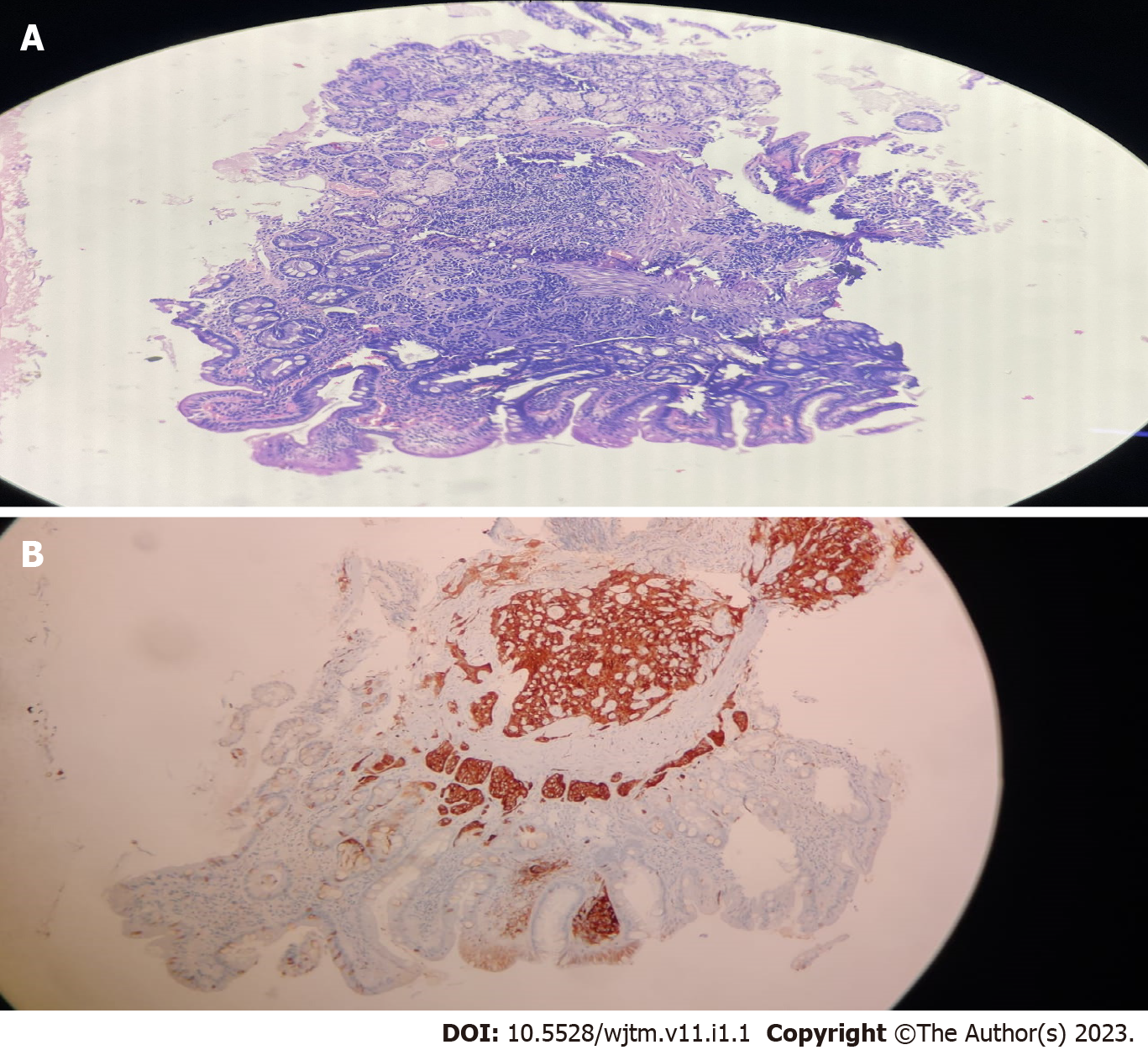

Biopsies taken during endoscopy were suggestive of the lesion arising from lamina propria and muscularis propria with monomorphic cells arranged in focal nesting pattern showing stippled chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm with immunohistochemistry (IHC) showing synaptophysin and chromogranin positivity. Ki67 of 1% suggestive of well-differentiated NET (G1) was seen in the first four patients, while the last patient had Ki67 of 3% suggestive of moderately differentiated NET (G2). World Health Organization 2022 classification of epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) for gastrointestinal (GI) and pancreaticobiliary tract used to classify the d-NET is presented in Table 1.

| Neuroendocrine neoplasms | Classification | Diagnostic criteria |

| Well differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (NET) | NET, grade 1 | < 2 mitoses/2 mm2 and/or Ki67 < 3% |

| NET, grade 2 | 2-20 mitoses/2 mm2 and/or Ki67 3-20% | |

| NET, grade 3 | > 20 mitoses/2 mm2 and/or Ki67 > 20% | |

| Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) | Small cell NEC | > 20 mitoses/2 mm2 and/or Ki67 > 20% (often > 70%), and small cell cytomorphology |

| Large cell NEC | > 20 mitoses/2 mm2 and/or Ki67 > 20% (often > 70%), and large cell cytomorphology |

We report 5 cases of d-NET, all of which are males and the age at presentation varied from 35 to 57 years. All of them were symptomatic at the presentation. Pain in the abdomen was seen in 4/5 (80%) and overt GI bleeding in 2/5 (40%) and one patient had recurrent oral aphthous ulcerations.

None of the patients mentioned in Table 2 had a significant past medical illness.

| Age/ gender | Clinical presentation | UGIE | CECT abdomen | EUS (linear EUS probe was used) | Management |

| 57 yr, male | Bloating, epigastric pain for 2 yr, vomiting for 15 d | Two nodular lesions with mucosal erosions in D1 | Normal | Two small sessile nodular lesions measuring 5 mm in the posterior wall of D1 from the second layer, homogenous echotexture, regular margins with no vascularity | Endoscopic submucosal resection |

| 52 yr, male | Epigastric pain for 15 d, melena for 1 d | Polypoid lesion of size 2 cm-2.5 cm in the lateral wall of D1 with superficial erosions | Lobulated, homogenously enhancing endoluminal lesion involving the D1 and D2 part of duodenum measuring 4.2 cm × 3 cm, partially involving the ampullary region of the duodenum with the normal common bile duct, pancreas shows tiny focal discrete areas of calcification with atrophy in the neck of the pancreas, there is also dilatation of pancreatic duct (5 mm) with features suggestive of chronic pancreatitis, few sub centimetric lymph nodes were noted in precaval region behind the uncinate process | 5 cm × 3 cm small homogenous submucosal swelling arising from the second layer in the D2 with no definite margins and no surface irregularity and no vascularity, heteroechoic pancreas with no calculi | Whipple procedure |

| 53 yr, male | Epigastric pain for 3 mo | Single sessile polypoidal lesion of size 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm in D1 with normal overlying mucosa | Normal | Single small sessile lesion measuring 5mm in the superior wall of D1 from the second layer, homogenous echotexture, regular margins with no vascularity | Endoscopic submucosal resection |

| 35 yr, male | Heartburn, epigastric pain, recurrent oral aphthous ulcerations for 4 mo | 3 nodular sub centimetric lesions in the anterior wall of the D1 segment of the duodenum | Normal | 3 small sessile lesions largest measuring 8mm in the anterior wall of D1 arising from the second layer, homogenous echotexture, regular margins with no vascularity | Endoscopic submucosal resection |

| 50 yr, male | Melena for 4 mo | 2 small polyps with ulceration in the D1 segment | Normal | 2 small sessile lesions largest measuring 5 mm in the anterior wall of D1 from the second layer, homogenous echotexture, regular margins with no vascularity | Endoscopic submucosal resection |

Neither the personal nor family history of the patients mentioned in Table 2 contributed to the diagnosis and manage

There were no significant/contributory findings on the general, systemic examination of the patients.

Lesions were found in the duodenal bulb in 5/5 patients, with one of them having the lesion extending towards the periampullary region. 2 or more lesions were found in 3/5 patients (60%). Lesion size varied from 5 mm to 25 mm among the cohort, of which 4/5 patients had sub-centimetric lesions. 4/5 patients had well-differentiated NET, whereas one patient had moderately differentiated NET.

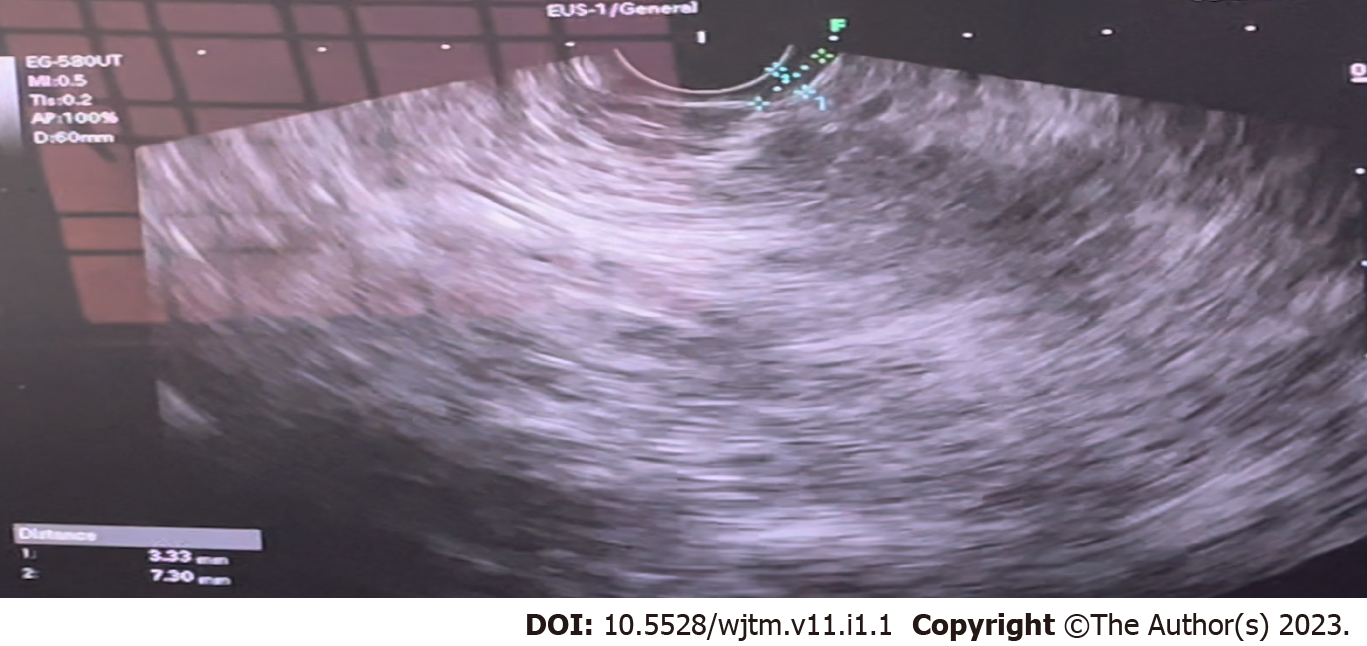

Figure 1 shows the endoscopic image of the d-NET of our case series. Figure 2 demonstrates the histopathology slides of the neuroendocrine tumor in hematoxylin and eosin staining whereas Figure 3 depicts the endoscopic ultrasound (US) image. Figure 4 also depicts the endoscopic image of the 52-year male patient with d-NET. Figure 5 depicts the IHC stain for synaptophysin which established the diagnosis. Based on the history, examination, and laboratory findings, all the above-mentioned patients were diagnosed with a non-functional duodenal neuroendocrine tumor.

4/5 patients underwent endoscopic therapy by using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and one patient was advised to undergo the Whipple procedure given the size of the lesion precluding endoscopic therapy.

Patients were followed up in our center on a 3-6 moly basis or whenever they are symptomatic and patient number 2 was advised to undergo the Whipple procedure was lost to follow up.

NET arise from the peptide neurons and neuroendocrine cells and can be functional or non-functional. NETs are seen in the GI tract (43%), lung (30), and pancreas (7%)[2]. Gastroenteropancreatic NETs (GEP-NETs) account for 0.4% to 1.8% of all GI malignancies[2].

DNETs comprise 1%-3% of primary duodenal tumors[3], 11% of small intestinal NETs, and 5%-8% of all GI-NETs. DNETs are slightly more common in males than females (1.5:1). The mean age of presentation of gastrinomas and somatostatinomas is 47 and 50 years, respectively[4]. The overall median age at diagnosis is 60-62 years[4]. The mean age at diagnosis of neuroendocrine carcinoma (NECs) patients is 66-70 years[4]. D-NETs include well-differentiated NETs, poorly differentiated NECs, and mixed neuroendocrine non-NENs.

The majority of d-NETs are found in the bulb and descending part of the duodenum, and 20% of dNETs are found in the periampullary region[5]. Non-functioning gastrin-producing NETs typically occur in the duodenal bulb, while all somatostatin-producing NETs are almost exclusive to the major and minor ampullary regions. D-NETs are often small, more than 75% are < 2 cm in size and located in mucosa or submucosa[6]; metastasis to lymph nodes is seen in 40%-60% and to the liver in 10% of cases at diagnosis[7].

Most of the d-NETs occur sporadically (75%-80%)[8]. A minority of tumors arise in genetic background, gastrinomas in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) syndromes, and somatostatin cell tumors in type 1 neurofibromatosis. Nearly 10% of d-NETs can occur as multiple tumors, which should raise suspicion of MEN-1. It has been reported that approximately 25%-33% of patients with d-NETs and Zollinger Ellison syndrome, actually have undiagnosed MEN-1[9]. The updated World Health Organization classification (2022) of epithelial NENs for the GI and pancreaticobiliary tract is presented in Table 1.

The majority of d-NETs are non-functional (90%) whereas only 10% are functional tumors[10]. The most common symptoms are abdominal pain (37%), upper GI bleeding (21%), anemia (21%), and jaundice (18%)[11].

The most common functional d-NET is Gastrinoma and the second most common is somatostatinoma[5]. The most common manifestation of the somatostatinoma syndrome of GI distress, gallstones, and diabetes is the presence of pancreatic tumors or extra-pancreatic tumors that exceed 4 cm in size. Gangliocytic paragangliomas are rare[12].

Upper GI endoscopy typically shows a single small sessile pale lesion in the duodenal cap or bulb. Endoscopic US can find tumors in the submucosa and is important for determining the layer of origin of the lesion as well as the depth of the invasion and the number of lymph nodes. Computed tomography (CT) is the initial imaging study for the evaluation of a NET, though magnetic resonance imaging is considered to be superior for the detection and follow-up of both primary tumors and liver metastases[13].

The majority of GEP-NETs can be visualized using somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS). 18F-deoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET) has significant uptake only in poorly differentiated tumors, and it should be performed only if SRS is negative. The use of FDG PET is mandatory in all patients with G3 d-NETs and is optional for G1 and G2 tumors[14].

The pathologic diagnosis is established according to morphology and architectural pattern and IHC staining. Protocol for histopathological examination of dNETs includes procedure done to acquire the biopsy sample, tumor site, size, focality, grade of differentiation, mitotic rate, Ki67 labeling index, histologic subtype, tumor margins, and extension, lymphovascular and perineural invasion, lymph node status.

Prognosis depends on according to the tissue of origin, the grading and differentiation, the stage, the aggressiveness, the functionality, the surgical outcome, and the presence of hereditary disease. The 5-year survival rate is 80%-85% with well-differentiated d-NETs and 72% in NEC[15].

Endoscopic resection, either with EMR or endoscopic submucosal dissection, is for tumors < 10 mm confined to the submucosa with no lymph node or distant metastases. Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) was feasible and effective in the management of large (> 10 mm) duodenal subepithelial lesions and a study on 20 patients[16] it was observed that there are higher rates of R0 resection with exposed EFTR method whereas the non-exposed EFTR method has been shown to have a lesser risk of peritoneal dissemination of tumor cells and extraluminal spillage of GI content and is also technically easier, faster to perform[17].

Surgical interventions are recommended in all tumors larger than 20 mm, sporadic gastrinomas, and all periampullary dNETs, after endoscopic methods in the case of G1 or G2 dNETs with positive margins, G3 histological grading, invasion into a muscular layer or lymphovascular system. Systemic treatment of patients with NETs involves chemotherapy, interferon-α, everolimus, and sunitinib. Ampullary tumors are treated as a separate entity. Somatostatin analogs should be used for G1 and G2 tumors, while cisplatin and etoposide should be used for G3 dNETs[18]. Everolimus may be effective for patients with G2 dNETs. PRRT should be used for patients with positive SRS and progressive disease. Results of immunotherapy using immune checkpoint inhibitors and the use of histone deacetylase inhibitors are promising in recent reports[19]. In ongoing clinical trials, surufatinib, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting immune cells and angiogenesis was found to be effective in treating NETs[20].

According to the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society[21] guidelines, when non-functional dNETs are completely removed by using endoscopic techniques, a follow-up visit, with upper GI endoscopy, US, or CT, and plasma chromogranin A (CgA) levels, should be performed at 6, 24, and 36 mo following such treatment. Surgical resection of dNETs should be followed up by CT, SRS, and CgA levels performed at 6 and 12 mo after surgery, and then annually for a minimum of 3 years. Re-evaluation of untreated patients with metastatic/inoperable dNETs should be performed at 3-6 moly intervals by CgA, CT, and/or US and SRS.

DNETs are rare tumors that require a higher degree of suspicion and as they present with few, nonspecific GI symptoms, all duodenal lesions need a biopsy and IHC staining for diagnosis. D-NETs are amenable to EMR, and they need to be kept under close follow-up.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bredt LC, Brazil; Martino A, Italy S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Rindi G, Mete O, Uccella S, Basturk O, La Rosa S, Brosens LAA, Ezzat S, de Herder WW, Klimstra DS, Papotti M, Asa SL. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2022;33:115-154. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 313] [Article Influence: 156.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Naik DV, Valtin H. Hereditary vasopressin-resistant urinary concentrating defects in mice. Am J Physiol. 1969;217:1183-1190. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1510] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2208] [Article Influence: 315.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Strinovi M, Kruljac I, Dabeli N, Nikoli M, Vrkljan M. Duodenal neuroendocrine tumors (d-NETs): challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Endocrine oncology and metabolism. 2016;15:168-173. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Naji M, Hodolic M, El-Refai S, Khan S, Marzola MC, Rubello D, Al-Nahhas A. Endocrine tumors: the evolving role of positron emission tomography in diagnosis and management. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33:54-60. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Albores-Saavedra J, Hart A, Chablé-Montero F, Henson DE. Carcinoids and high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the ampulla of vater: a comparative analysis of 139 cases from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program-a population based study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1692-1696. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Scherübl H, Jensen RT, Cadiot G, Stölzel U, Klöppel G. Neuroendocrine tumors of the small bowels are on the rise: Early aspects and management. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:325-334. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Vanoli A, La Rosa S, Klersy C, Grillo F, Albarello L, Inzani F, Maragliano R, Manca R, Luinetti O, Milione M, Doglioni C, Rindi G, Capella C, Solcia E. Four Neuroendocrine Tumor Types and Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Duodenum: Analysis of 203 Cases. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104:112-125. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hoffmann KM, Furukawa M, Jensen RT. Duodenal neuroendocrine tumors: Classification, functional syndromes, diagnosis and medical treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:675-697. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 128] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gibril F, Schumann M, Pace A, Jensen RT. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective study of 107 cases and comparison with 1009 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83:43-83. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 195] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jensen RT, Rindi G, Arnold R, Lopes JM, Brandi ML, Bechstein WO, Christ E, Taal BG, Knigge U, Ahlman H, Kwekkeboom DJ, OToole D. Frascati Consensus Conference; European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Well-differentiated Duodenal Tumour/Carcinoma (Excluding Gastrinomas). Neuroendocrinology. 2007;84:165-172. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xavier S, Rosa B, Cotter J, Gastroenterology DO, Ave CHDA, Laboratory I, Minho UO, Gualtar CD, Institute LHS, Sciencs SOH. Small bowel neuroendocrine tumors: From pathophysiology to clinical approach. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology. 2016;. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Okubo Y, Yokose T, Motohashi O, Miyagi Y, Yoshioka E, Suzuki M, Washimi K, Kawachi K, Nito M, Nemoto T, Shibuya K, Kameda Y. Duodenal Rare Neuroendocrine Tumor: Clinicopathological Characteristics of Patients with Gangliocytic Paraganglioma. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:5257312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Reznek RH. CT/MRI of neuroendocrine tumours. Cancer Imaging. 2006;6:S163-S177. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Junik R, Drobik P, Małkowski B, Kobus-Błachnio K. The role of positron emission tomography (PET) in diagnostics of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (GEP NET). Adv Med Sci. 2006;51:66-68. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Man D, Wu J, Shen Z, Zhu X. Prognosis of patients with neuroendocrine tumor: a SEER database analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:5629-5638. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Nabi Z, Pradev I, Basha J, Reddy DN, Darishetty S. Exposed versus non-exposed endoscopic full thickness resection for duodenal sub-epithelial lesions: A tertiary care center experience. (with videos). iGIE. 2023;2:154-160. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Granata A, Martino A, Zito FP, Ligresti D, Amata M, Lombardi G, Traina M. Exposed endoscopic full-thickness resection for duodenal submucosal tumors: Current status and future perspectives. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;14:77-84. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pavel M, Baudin E, Couvelard A, Krenning E, Öberg K, Steinmüller T, Anlauf M, Wiedenmann B, Salazar R; Barcelona Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with liver and other distant metastases from neuroendocrine neoplasms of foregut, midgut, hindgut, and unknown primary. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:157-176. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 608] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 567] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cives M, Pelle' E, Quaresmini D, Rizzo FM, Tucci M, Silvestris F. The Tumor Microenvironment in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Biology and Therapeutic Implications. Neuroendocrinology. 2019;109:83-99. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Xu J. Current treatments and future potential of surufatinib in neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021;13:17588359211042689. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Delle Fave G, O'Toole D, Sundin A, Taal B, Ferolla P, Ramage JK, Ferone D, Ito T, Weber W, Zheng-Pei Z, De Herder WW, Pascher A, Ruszniewski P; Vienna Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Gastroduodenal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:119-124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 312] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |