Published online Jan 18, 2025. doi: 10.5317/wjog.v14.i1.102334

Revised: December 18, 2024

Accepted: January 9, 2025

Published online: January 18, 2025

Processing time: 93 Days and 22.9 Hours

Fear of childbirth (FoC) is a widespread issue that impacts the health and well-being of mothers and newborns. However, there is inconsistency regarding the prevalence of FoC in the and there is limited research on the prevalence of FoC among Australian pregnant women.

To investigate the prevalence of FoC, its risk factors and birth outcomes in Aust

In this prospective cohort quantitative study, 212 multiparous women were re

Out of 212 participants, 24% experienced a high level of FoC and 7% experienced severe FoC. The χ2 test results revealed that a family income of ≤ $100000, no alcohol intake during pregnancy, pre-existing health problems, previous caesarean section (emergency or planned), and previous neutral/traumatic childbirth experiences were significantly associated with higher levels of FoC (P < 0.05). Other risk factors included being moderately to very worried and fearful about the upcoming birth, having severe to extremely severe anxiety throughout pregnancy, and expressing low relationship satisfaction. According to multivariable logistic regression, the odds of a high level of FoC were higher in women with anxiety, a history of traumatic childbirth experience, a history of sexual assault during childhood, pre-existing health problems, and lower relationship satisfaction (P < 0.05).

High-severe levels of FoC are experienced by pregnant multiparous women and are affected by several demo

Core Tip: High-severe levels of fear of childbirth are common in pregnant multiparous women, are associated with several demographics and psychosocial factors and can affect birth outcomes. It is essential to develop customized maternity care and prenatal education programs in maternity facilities. To empower and support women and improve perinatal outcomes, their unique needs must be recognized, and assistance in coping with fear and anxiety must be made available in a way that contributes to a positive pregnancy experience.

- Citation: Li RX, Asgharvahedi F, Khajehei M. Prevalence of fear of childbirth, its risk factors and birth outcomes in Australian multiparous women. World J Obstet Gynecol 2025; 14(1): 102334

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v14/i1/102334.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5317/wjog.v14.i1.102334

Every woman's pregnancy is a unique and personal experience[1]. Women's pregnancy and childbirth experiences can be multifaceted, meaning they may be both positive and negative at the same time. Childbirth is a defining moment in the lives of many women, but for some, the experience of childbirth can cause profound fear[2]. The fear may hover throug

In a systematic review in 2018[4], the global prevalence of fear of childbirth (FoC) was reported to vary between 6.3% and 14.8%, representing Europe, Australia, Canada and the United States. Another earlier systematic review of 33 studies conducted in 18 countries demonstrated that FoC occurs in 3.7% to 43% of pregnant women[5]. A study conducted in Thailand[6] suggested a prevalence of moderate FoC of 16.1% among pregnant women, which was similar to most western studies, but identified a significantly lower prevalence in severe FoC with 0.7% prevalence compared to other western studies. The study by Zhou et al[7] also indicated a high prevalence of FoC among Chinese women, with 21% of multiparous women experiencing a moderate to severe level of fear. A more recent study among 659 English-speaking pregnant women living in Canada showed that 7.1% of them experienced FoC[8].

Variations in the prevalence of FoC could be due to several confounding factors. One of these factors is parity. According to Toohill et al[9], the prevalence of FoC in Australian nulliparous women is approximately 25%, and 14% in multiparous women. In contrast, another population-based study of FoC in women with singleton births in Finland in 1997–2010 showed that 4.5% of multiparous women and 2.5% of nulliparous women experience FoC[10]. Although the prevalence may be generally perceived to be lower in multiparous women, it is not any less significant. According to Dencker et al[11], both nulliparous and multiparous women may experience the same amount of fear; however, the causes may differ. While inexperience and a lack of education may cause fear in nulliparous women, past negative expe

Evidence has shown that the prevalence of FoC in pregnant women has grown in recent years[16], including 10% in developed countries and 25% in developing countries. Also, a significant difference has been shown between the pre

For example, in European research, the prevalence of FoC was lower than that in Australia[9,12,16,20]. The reason for variability when investigating the prevalence of FoC could be methodological differences (such as using different tools to measure FoC, administration of different cut-off points for each tool, and using self-reported tools vs clinical interviews). The most common tool to measure FoC in the literature is the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire (W-DEQ), with translations into several languages worldwide[5]. However, different studies have used various cut-off points to categorize women’s level of FoC, including a cut-off score of equal to or greater than 65, 85 or 100. Fear of Birth Scale (FoBS) is another tool that has been commonly used in previous research. However, some studies have used a cut-off score of 50, while others considered a score of 54 or above to indicate a high level of FoC. Variation in the prevalence of FoC can also depend on the method of data collection. Multiple studies have assessed the prevalence of FoC using self-reported questionnaires, while others have applied diagnostic interviews using measurement of physiological indices, ensuring the women accurately indicate their FoC[4].

Multiple factors, classified as biological, psychological, cultural, and social, contribute to FoC[3]. Previous negative experiences, as well as stories of pain, suffering, and shame, may serve as risk factors for FoC[3,12]. Other risk factors identified in the research include mental health, age, education, employment, and marital status[7,9,21,22]. Nevertheless, some studies diverged in determining the effect of each risk factor, especially concerning demographics, where cultural factors may be a major contributor to FoC[9,22-24].

Timely detection and treatment of FoC is essential, as it has been shown to be associated with increased use of pharmacological pain relief during labour, delayed labour progress, higher rates of instrumental vaginal births, emergency and elective caesarean section, post-traumatic stress disorder, postpartum depression, and anxiety in subsequent pregnancies[14,20,25,26]. However, the association between FoC and poorer birth outcomes is multifaceted and can be moderated by a variety of confounding factors. For example, advanced maternal age (> 35 years), maternal overweight or obesity, pre-existing health problems, history of sexual abuse, previous emergency caesarean section, and previous 3rd or 4th degree tear can affect the progress of labour and birth and may result in negative birth outcomes. Thus, these factors need to be accounted for when investigating the association between FoC and birth outcomes in multiparous women[11].

To our knowledge, research on the FoC among the population of multiparous women living in Sydney, Australia, is scarce. While antenatal mental health problems have been addressed in previous research[27], previous studies primarily focused on nulliparous women, resulting in a lack of an in-depth and sophisticated understanding of this specific context among multiparous women[28]. Also, screening for mental health issues in the current healthcare system is variable and mainly covers general aspects of anxiety and depression and mainly counts on women’s self-awareness[29]. Many symptoms remain overlooked and concealed until birth[30,31]. Furthermore, labour and birth experiences and outcomes could be different in women living in Australia compared to women in other countries. For example, a recent study cross-sectional national survey of Australian women[32] showed that women wish to have less medical intervention and more freedom of choice to have a normal vaginal birth. However, an observational study of 72 low and middle income coun

Hence, we conducted this study to investigate the prevalence of FoC during pregnancy in Australian multiparous women who attended a tertiary hospital in Western Sydney. Our specific focus on multiparous women adds to the growing body of knowledge in this understudied group. In the present study, we aimed to fill the gaps in the literature by combining different measurements and using a comprehensive questionnaire that covers aspects of FoC, psychology, relationship status and female sexual function throughout the perinatal period. For a more comprehensive approach and to address the issue of measuring tools, we added the standardized FoBS to be used in conjunction with W-DEQ. We also explored factors affecting the occurrence of FoC, combining different tools and using a comprehensive questionnaire that covers aspects of FoC, psychology, relationship status and female sexual function throughout the perinatal period. Assessment of birth outcomes in women with high levels of FoC was another secondary objective of this study.

Study participants were recruited from antenatal clinics at Westmead Hospital from 2019 to 2022.

This prospective cohort study was part of a larger mixed-methods research. Results of the comparison of FoC between nulliparous and multiparous women has been published elsewhere[34]. The authors have read the STROBE Statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement.

This study received full ethical approval from Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee prior to its commencement (HREC Ref: 2019/ETH09781). The women signed the written consent forms before participating in the study. No identifiable data have been presented. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki for the recruitment of human participants, study conduct and dissemination of results.

The primary outcome of the study was the prevalence of FoC among multiparous women. Toohil et al[9] reported incidences of FoC of 18% (n = 801) in populations of multiparous women. The prevalence of multiparous women is roughly 60% (based on our hospital records) in the cohort attending antenatal clinic at Westmead Hospital. Thus, 212 multiparous women were required to be analyzed with 80% power and at a significance level of 0.05. The power cal

Pregnant women were invited to participate in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Age 18 years or older; (2) Second or third trimester of pregnancy with a singleton fetus; (3) Low-risk pregnancy; (4) Citizen or permanent resident of Australia; and (5) Multiparity.

Women were excluded from the study if they: (1) Did not speak English; and (2) Had a high-risk pregnancy or had been clinically diagnosed with perinatal mental health issues. A high-risk pregnancy can lead to increased risk of pre

Primary outcome: The primary outcome of this study was the prevalence of FoC in multiparous women.

Secondary outcome: The secondary outcomes were: (1) The association between FoC during pregnancy and sociodemographic factors, obstetric and medical history, depression, anxiety, stress, quality of relationship with the partner, sexual function; and (2) Birth outcomes including maternal outcomes (use of labour analgesia, mode of birth, perineal damage or episiotomy, postpartum hemorrhage, length of postnatal hospital stay) and neonatal outcomes [gestational age at birth, Apgar score at 5 minutes, birth weight, special care nursery or neonatal intensive unit (SCN/NICU) admission afterbirth, type of feeding at discharge].

We used two standardized questionnaires to investigate our primary outcome, the prevalence of FoC, among the study participants, as follows. The cut-off score for each questionnaire has been selected based on the highest level of sensitivity and specificity of the tool at that cut-off point.

The W-DEQ scale was used to assess FoC during pregnancy based on a woman's cognitive evaluation of childbirth[26]. This is a 33-item questionnaire with scores ranging from ‘not at all’ (0) to ‘extremely’ (5), for a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 165. A higher score indicates a higher severity of FoC. According to Ryding et al[26], a score of ≤ 37 suggests low fear, 38–65 shows moderate FoC, 66–87 indicates a high level of FoC, and a score of ≥ 85 is classified as severe FoC, with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 93.8%. The validity and reliability of this tool have been demonstrated in previous studies (Cronbach's α = 0.70-0.91)[9,26,35]. For the purpose of this study, we used a cut-off score of ≥ 66.

The FoBS contains a two-item visual analogue scale that explores worry and fear about an upcoming birth by asking

After a comprehensive literature review, a multi-section self-reported questionnaire was designed, requesting informa

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) is a collection of three self-reporting measures used to assess depression, anxiety, and stress during pregnancy. Participants were asked to use 4-point severity scales to rate the extent to which they had experienced each state over the past week. The depression, anxiety, and stress scores were derived by adding the results for the relevant items[39]. We used a cut-off score of 10 to indicate a moderate level of depression, anxiety and stress, and a cut-off of ≥ 11 to suggest a severe to extremely severe level of the abovementioned mental health problems, with a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 64%[40]. The validity and reliability of this tool (Cronbach's α = 0.72–0.90) have been proven in previous studies[41-43].

The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) was used to assess female sexual function during pregnancy. This scale is a valid and reliable tool (Cronbach's α = 0.76–0.93)[44] that consists of 19 multiple-choice questions meant to gather information about women's sexual function during the previous four weeks. Six major categories of sexual function were evaluated: Desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. A Likert scale was used to grade the items. Ques

The Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) was used to measure relationship satisfaction during pregnancy. It has been identified as a valid and reliable measure (Cronbach's α = 0.86–0.91) for assessing relationship satisfaction within any form of partnered relationship by Vaughn and Baier[48] and Hendrick[49] and “is not limited to marriage relationships”[48]. It consisted of seven multiple-choice questions, with items scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not satisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). A mean score of 4 or higher indicated relationship satisfaction, whereas a score of less than 4 suggested relationship dissatisfaction[49].

All pregnant women who attended antenatal clinics at Westmead Hospital were approached by the first author. They were provided with a copy of the information sheet and were explained about the purpose of the study, inclusion/exclusion criteria, right to withdraw, risks and benefits to them. They were then given sufficient time to read the infor

Labour and birth details for all the participants were collected from the eMaternity database. This database is routinely used to record perinatal details of all women who attend our hospital. The baseline and birth details were linked using the study IDs.

SPSS Advanced Statistics version 24.0 was used to analyze the data (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). After completing the online questionnaire on Survey Monkey, participants' replies were downloaded into an Excel file. Afterwards, each response choice was coded and assigned a numerical value. The complete dataset was imported into SPSS software for analysis. The sociodemographic, obstetric and medical history, mental health, sexual function, relationship data (indepen

Continuous variables were shown as mean ± SD, whereas categorical variables were shown as frequency (%) in rele

Independent samples t-test was used to compare continuous non-skewed variables between women with high and low levels of FoC; these are presented as means with standard deviations. For skewed continuous data, the Mann-Whitney U test was used; these data are presented as medians with interquartile ranges.

The role of multiple factors influencing the likelihood of FoC was investigated using multivariable logistic regression analysis (backward Wald). The covariates used for multivariable logistic regression comprised of those variables that were already proven in the literature to be related to the outcome[11], including categorical demographics (age, educa

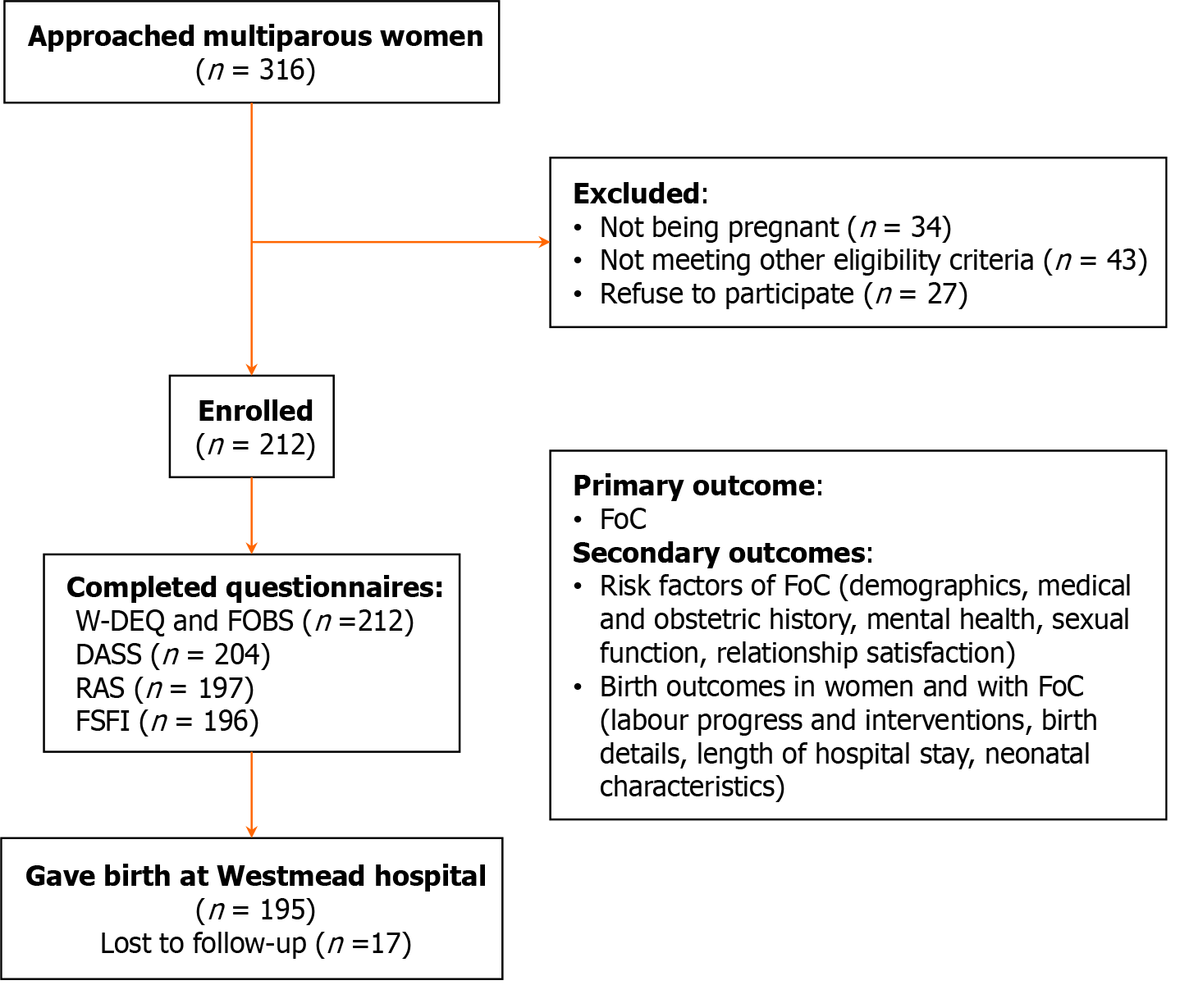

A total of 212 women completed the W-DEQ and FoBS questionnaires (our primary outcome). However, only 204 women completed the DASS, and 197 answered the RAS and FSFI questions (Figure 1).

According to the W-DEQ scores, out of 212 pregnant women, 62 (29%), 85 (40%), 50 (24%) and 15 (7%) reported low, moderate, high and severe FoC, respectively (51 ± 23.4). The FoBS revealed that 89 (42%) women were moderately to very worried about the approaching birth (38 ± 28.8), and 85 (40%) had moderate to high fear about the upcoming birth (36 ± 28.5).

Out of 212 pregnant women who completed the W-DEQ and FoBS, only 143 completed the DASS and 139 completed the RAS and FSFI.

Results of the χ2 analysis indicated that FoC was statistically significantly associated with family income ≤ $100000, no alcohol intake during their pregnancy, pre-existing health problems, previous caesarean section birth and previous trau

| Variable | Low-moderate FoC (n = 147) | High-severe FoC (n = 65) | P value |

| Age | 0.542 | ||

| < 25 | 6 (4) | 2 (3) | |

| 25–35 | 102 (69) | 41 (63) | |

| > 35 | 39 (27) | 22 (34) | |

| Education | 0.314 | ||

| No formal education | 4 (3) | 5 (8) | |

| High school certificate or lower | 33 (22) | 14 (22) | |

| Diploma or undergraduate degree | 82 (56) | 31 (48) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 28 (19) | 15 (23) | |

| Country of origin | 0.092 | ||

| Australia | 51 (35) | 15 (23) | |

| Other | 96 (65) | 50 (77) | |

| Country of birth | 0.069 | ||

| Australia | 55 (37) | 16 (25) | |

| Other | 92 (63) | 49 (75) | |

| Employment status | 0.704 | ||

| No formal occupation | 26 (18) | 17 (26) | |

| Stopped working due to pregnancy | 41 (28) | 16 (25) | |

| Casual worker | 6 (4) | 3 (5) | |

| Part-time | 25 (17) | 9 (14) | |

| Full-time | 49 (33) | 20 (31) | |

| Marital status | 0.058 | ||

| Married or de facto | 138 (94) | 57 (88) | |

| Divorced/separated/widow | 5 (3) | 2 (3) | |

| Single | 4 (3) | 6 (9) | |

| Annual family income | 0.018 | ||

| < $50000 | 35 (24) | 18 (28) | |

| $50000–100000 | 49 (33) | 32 (49) | |

| > $100000 | 63 (43) | 15 (23) | |

| Living situation | 0.262 | ||

| With partner | 109 (74) | 41 (63) | |

| With family/friends | 32 (22) | 20 (32) | |

| Alone | 6 (4) | 4 (6) | |

| Support person | 0.4832 | ||

| Herself only | 13 (9) | 5 (8) | |

| Others | 134 (91) | 60 (92) | |

| Major life stressor | 0.148 | ||

| No | 101 (69) | 38 (59) | |

| Yes | 46 (31) | 27 (42) | |

| Alcohol intake | 0.0692 | ||

| No | 134 (91) | 64 (99) | |

| Yes | 13 (9) | 1 (2) | |

| Cigarette smoking | 0.1572 | ||

| No | 133 (91) | 63 (97) | |

| Yes | 14 (10) | 2 (3) | |

| History of sexual assault during childhood | 0.8112 | ||

| No | 131 (89) | 59 (91) | |

| Yes | 16 (11) | 6 (9) | |

| History of sexual assault during adulthood | 0.2352 | ||

| No | 135 (92) | 63 (97) | |

| Yes | 12 (8) | 2 (3) | |

| Age (range 22–43 years) | 32 ± 4.4 | 33 ± 4.3 | 0.155 |

| Body mass index (range 14–52) | 28 ± 5.9 | 28 ± 5.9 | 0.689 |

| Years living in Australia (range 05–43) | 18 ± 12.9 | 17 ± 11.6 | 0.311 |

| Variable | Low–moderate FoC (n = 147) | High–severe FoC (n = 65) | P value |

| Pre-pregnancy anxiety/depression | 0.089 | ||

| No | 107 (73) | 43 (66) | |

| Anxiety only | 15 (10) | 8 (12) | |

| Depression only | 4 (3) | 7 (11) | |

| Both | 21 (14) | 7 (11) | |

| Pre-existing health problem | 0.003 | ||

| No | 108 (74) | 34 (52) | |

| Yes | 39 (27) | 31 (48) | |

| Previous mode of birth | 0.015 | ||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 82 (56) | 32 (49) | |

| Instrumental | 30 (20) | 5 (8) | |

| Emergency caesarean section | 25 (17) | 19 (29) | |

| Planned caesarean section | 10 (7) | 9 (14) | |

| Previous childbirth experience | < 0.001 | ||

| Neutral | 46 (31) | 28 (43) | |

| Empowering | 73 (50) | 14 (22) | |

| Traumatic | 28 (19) | 23 (35) | |

| Previous 3rd or 4th degree tear | 0.541 | ||

| No | 112 (76) | 52 (80) | |

| Yes | 35 (24) | 13 (20) | |

| Attended antenatal educational classes | 0.659 | ||

| No | 127 (86) | 58 (89) | |

| Yes | 20 (14) | 7 (11) | |

| Type of conception | 0.178 | ||

| Planned | 100 (68) | 38 (59) | |

| Unplanned | 47 (32) | 27 (42) | |

| Gestational age at baseline (range 14–41 weeks) | 30+5 ± 7+1 | 29 ± 7+1 | 0.521 |

| Expected length of hospital stay after vaginal birth (range 0–7 days) | 2 ± 1.1 | 2 ± 1.2 | 0.206 |

| Expected length of hospital stay after caesarean section (range 0–10 days) | 3 ± 1.9 | 3 ± 2.0 | 0.927 |

| Variable | Low–moderate FoC | High–severe FoC | Unadjusted risk ratio (95%CI) | t value (degree of freedom) | P value |

| FoBS-Feeling calm about the approaching birth | < 0.001 | ||||

| Moderately to very calm (< 50) | 100/147 (68%) | 23/65 (35%) | 0.40 (0.3–0.6) | ||

| Moderately to very worried (≥ 50) | 47/147 (32%) | 42/65 (65%) | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | ||

| mean ± SD (range 0–100) | 31 ± 26.3 | 53 ± 28.3 | 22.4 (14.5–30.3)3 | -5.57 (210) | < 0.001 |

| FoBS-Feeling fear about the approaching birth | < 0.001 | ||||

| No or mild fear (< 50) | 103/147 (70%) | 24/65 (37%) | 0.39 (0.23–0.6) | ||

| Moderate to high fear (≥ 50) | 44/147 (30%) | 41/65 (63%) | 1.67 (1.3–2.0) | ||

| mean ± SD (range 0–100) | 30 ± 26.8 | 50 ± 27.5 | 19.8 (11.8–27.7)3 | -4.91 (210) | < 0.001 |

| DASS-Depression | 0.2432 | ||||

| Mild to moderate (0–10) | 139/143 (97%) | 57/61 (93%) | 0.58 (0.3–1.2) | ||

| Severe to extremely severe (≥ 11) | 4/143 (3%) | 4/61 (7%) | 1.42 (0.7–2.9) | ||

| mean ± SD (range 0–21) | 2 ± 3.5 | 4 ± 4.4 | 1.8 (0.6–2.9)3 | -3.02 (202) | 0.001 |

| DASS-Anxiety | 0.005 | ||||

| Mild to moderate (0-10) | 126/143 (88%) | 44/61 (72%) | 0.52 (0.3–0.8) | ||

| Severe to extremely severe (≥ 11) | 17/143 (12%) | 17/61 (28%) | 1.48 (1.1–2.1) | ||

| mean ± SD (range 0–20) | 3 ± 3.6 | 5 ± 4.5 | 1.3 (0.1–2.5)3 | -2.18 (202) | 0.015 |

| DASS-Stress | 0.4562 | ||||

| Mild to moderate (0–10) | 138/143 (97%) | 57/61 (93%) | 0.66 (0.3–1.4) | ||

| Severe to extremely severe (≥ 11) | 5/143 (4%) | 4/61 (7%) | 1.27 (0.7–2.3) | ||

| mean ± SD (range 0–21) | 4 ± 4.1 | 6 ± 4.9 | 1.8 (0.5–3.1)3 | -2.75 (202) | 0.003 |

| RAS (n = 197) | 0.001 | ||||

| Higher relationship satisfaction (≥ 4) | 122/139 (88%) | 39/58 (67%) | 2.18 (1.4–3.3) | ||

| Less relationship satisfaction (< 4) | 17/139 (12%) | 19/58 (33%) | 0.62 (0.4–1.0) | ||

| mean ± SD (range 2–5) | 5 ± 0.7 | 4 ± 0.7 | 0.4 (0.2–0.6)3 | 4.45 (195) | < 0.001 |

| FSFI (n = 198) | 0.502 | ||||

| Normal sexual function | 25/139 (18%) | 8/57 (14%) | 0.81 (0.4–1.5) | ||

| Sexual dysfunction | 114/139 (82%) | 49/57 (86%) | 1.08 (0.9–1.4) | ||

| mean ± SD (range 1–34) | 17 ± 9.3 | 16 ± 9.3 | 1.9 (-1.0–4.8)3 | 1.35 (195) | 0.089 |

| FSFI sub-groups, mean ± SD | |||||

| Desire (range 1–6) | 3 ± 1.1 | 3 ± 1.0 | 0.3 (-0.1–0.6) | 1.66 (195) | 0.105 |

| Arousal (range (0–6) | 3 ± 2.0 | 3 ± 1.9 | 0.5 (-0.1–1.1) | 1.74 (195) | 0.093 |

| Lubrication (0–6) | 3 ± 2.2 | 3 ± 2.2 | 0.6 (-0.1–1.3) | 1.77 (195) | 0.085 |

| Orgasm (range 0–6) | 3 ± 2.4 | 3 ± 2.2 | 0.7 (-0.03–1.4) | 1.92 (195) | 0.061 |

| Satisfaction (range 0–6) | 3 ± 1.6 | 3 ± 1.7 | 0.02 (-0.05–0.6) | 0.17 (195) | 0.913 |

| Pain (range 0–6) | 2 ± 2.5 | 2 ± 2.3 | -0.2 (-1.0–0.5) | -0.54 (195) | 0.558 |

Results of the adjusted multivariable logistic regression showed that the odds of having high to severe FoC were 3.79 times greater in women with anxiety, 2.45 times higher in women who had previous traumatic childbirth experience, 5.25 times greater in women with a history of sexual assault during childhood, 2.92 times higher in women with pre-existing health problems during pregnancy, 2.92 times greater in women with pre-existing health problems and 5.28 times higher in women who reported less relationship satisfaction (Table 4).

| Variable | Crude OR | Unadjusted 95%CI | Adjusted OR | Adjusted 95%CI | P value |

| DASS Anxiety | < 0.001 | ||||

| Mild to moderate (0-10) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Severe to extremely severe (≥ 11) | 2.44 | 0.59–1.09 | 3.79 | 1.35–5.61 | |

| Previous traumatic childbirth experience | 0.033 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 2.12 | 1.21–4.48 | 2.45 | 1.15–3.98 | |

| History of sexual assault during childhood | 1.11–4.81 | 0.036 | |||

| No | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.20 | 0.45–3.22 | 5.25 | 1.11–4.81 | |

| Pre-existing health problem pregnancy | 0.004 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 2.53 | 1.37–4.64 | 2.92 | 1.40–6.12 | |

| RAS | < 0.001 | ||||

| Higher relationship satisfaction (≥ 4) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Less relationship satisfaction (< 4) | 3.50 | 1.67–7.38 | 5.28 | 2.15–6.98 |

Out of 212 participants, 195 women gave birth in our hospital (17 lost to follow-up) (Figure 1). For the calculation of epidural/spinal, episiotomy and third- or fourth-degree tear, we excluded those women who had caesarean section birth.

Compared to women with low-moderate FoC, women with high-severe FoC were more likely to have neonatal admis

| Variable | Low-moderate FoC (n = 133) | High-severe FoC (n = 62) | RR (95%CI) | P value |

| Maternal | ||||

| Epidural/spinal | 0.204 | |||

| No | 61/94 (65%) | 19/36 (53%) | 0.70 (0.40–1.21) | |

| Yes | 33/94 (35%) | 17/36 (47%) | 1.16 (0.92–1.46) | |

| Episiotomy3 | 0.576 | |||

| No | 80/94 (85%) | 32/36 (89%) | 1.29 (0.52–3.20) | |

| Yes | 14/94 (15%) | 4/36 (11%) | 0.92 (0.70–1.21) | |

| Third- or fourth-degree tear3 | 1.000 | |||

| No | 92/94 (98%) | 36/36 (100%) | ||

| Yes | 2/94 (2%) | 0 | ||

| Mode of birth | ||||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 87 (59%) | 34 (52%) | 0.83 (0.55–1.24) | 0.351 |

| Instrumental | 7 (5%) | 2 (3%) | 0.72 (0.21–2.47) | 0.7252 |

| Caesarean section | 39 (27%) | 26 (40%) | 1.51 (1.01–2.52) | 0.050 |

| Cumulative blood loss (range 50-6500 millilitres) | 300 (200–400) | 300 (235–400) | 0.365 | |

| Total duration of labour (range 1-26.4 hours)3 | 2.3 (2.3–3.6) | 1.2 (0.1–3.5) | 0.684 | |

| Length of postnatal hospital stay (range 4-163 hours) | 45.5 (24–72) | 43.5 (24–60) | 0.855 | |

| Neonatal | ||||

| Gestational age at birth (range 252-42.0 weeks) | 38.9 ± 2.1 | 38.7 ± 1.5 | -0.17 (-0.75-0.41) | 0.559 |

| Apgar score at 5 minutes (range 1-9) | 8.8 ± 0.9 | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 0.09 (-0.16–0.34) | 0.467 |

| Birth weight (range 800-4685 g) | 3291.2 ± 550.9 | 3333.3 ± 614.5 | 42.04 (-131.4-215.5) | 0.633 |

| Resuscitation after birth | 0.716 | |||

| No | 106 (80%) | 48 (77%) | 0.91 (0.56–1.48) | |

| Yes | 27 (20%) | 14 (23%) | 1.05 (0.82–1.34) | |

| SCN/NICU admission after birth | 0.006 | |||

| No | 119 (90%) | 46 (74%) | 0.52 (0.35–0.79) | |

| Yes | 14 (11%) | 16 (27%) | 1.55 (1.04–2.29) | |

| Received infant formula during hospital stay | 0.273 | |||

| No | 87/123 (71%) | 35/56 (63%) | 0.78 (0.50–1.21) | |

| Yes | 36/123 (29%) | 21/56 (38%) | 1.13 (0.90–1.42) | |

Our study aimed to investigate the prevalence and risk factors of FoC among pregnant Australian multiparous women. We discovered that 24% of individuals had a high FoC. This conclusion is consistent with other findings in the literature, which revealed a prevalence of high FoC ranging from 3.2% to 43%[5]. The prevalence of severe FoC (7%) in our study was similarly comparable with the findings of a Finnish study, in which the measured prevalence for severe FoC using W-DEQ was 7.7%[16]. Despite these findings, the prevalence of severe FoC in our research was greater than in a recent Australian study, where 3.6% of multiparous women who answered the questions on W-DEQ experienced severe FoC[9]. In the Finnish study[16], the participants were recruited regardless of their gestational age, parity or the reason for visiting the maternity outpatient clinics. As such, all nulliparous, primiparous and multiparous women were included in that study. Also, most women at 12-19 weeks of gestation attended the clinic for their routine ultrasound visits. In the Australian study[9], the majority of participants were in their second trimester of pregnancy (11–25 weeks), 74% of the participants were born in Australia (compared to one-third in our study), and the study sample included both nullipa

Another potential explanation for such a large discrepancy might be the coincidence of our data-collecting period with the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic. According to recent research, women were at a higher risk of developing mental health disorders during the pandemic, which may have led to a higher prevalence of severe FoC[50,51]. Another rationale for contradictions within the literature is the use of different research methodologies or data collection tools across studies, as explained earlier. Further to these, fear is not a stable notion and can be influenced by a variety of confounding circumstances, such as previous childbirth experiences and cultural factors[22]. Earlier re

FoC is related to various risk factors such as women’s personal, internal and external conditions[11]. Our study revealed that FoC was statistically significantly associated with anxiety, previous traumatic childbirth experiences, history of sexual assault during childhood, pre-existing health problems and relationship dissatisfaction with the partner. Earlier literature has indicated that demographic factors may escalate childbirth-related stress and affect women’s anticipation or experience of the birth process. For example, a population-based study in Norway[53] showed that poor social support and a previous negative birth experience strongly impacted the participants’ FoC. Also, according to a systematic review in 2021[54], there is a link between child sexual abuse, anxiety disorders and traumatic childbirth with an increased likelihood of medical interventions during labour and birth. While there is variation in the rate of child sexual abuse between countries ranging from 2% to 53%, pregnant women with a history of childhood sexual abuse show different behaviors. For example, they are more likely to drink alcohol during pregnancy, have eating disorders, preterm birth and an infant with low birth weight and developmental issues[54].

Our finding on previous negative/traumatic birth experiences corroborates those of Hall et al[55] and Toohill et al[9], who found that FoC was associated with past negative birth experiences. Negative birth experiences may lead to subse

Although our study did not find a statistically significant association between FoC and the participant’s country of birth or country of origin, it is noteworthy to mention that most women attending our hospital are from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Some of them have already had the experience of giving birth in other countries with different perinatal care systems compared to Australia. This could have contributed to their high–severe level of FoC despite having a previous positive birth experience. However, there is conflicting evidence in the literature about the relationship between these risk factors and FoC. The discrepancy may be explained by differences in socio-cultural-demographic factors among studies, particularly on an international scale. Personal beliefs about perceiving childbirth as a risky medical occasion, cultural attitudes for or against normal vaginal birth, prior negative experience of busy or unhygienic birthing rooms, and fear of insufficient support from medical staff all contribute to FoC in different studies[5].

Several aspects of mental health have been linked to FoC. The current study established a relationship between severe to extremely severe anxiety and an elevated risk of FoC. This finding is consistent with the reports by Nordeng et al[1], who proposed a link between FoC and anxiety. Also, the study by Størksen et al[53], using the WEDQ cut-off point of 85, showed a strong association between impaired mental health and FoC. Contrasting with prior literature, we did not identify a statistically significant relationship between FoC, depression, and stress using the DASS tool[1,2,7]. This could have been due to the use of different research methodologies or different tools to investigate women’s mental health. We used self-reported DASS-21 to estimate women’s depression, anxiety and stress. In contrast, Størksen et al[53] used Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to screen for symptoms of depression and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist to investigate participants’ symptoms of anxiety.

Although we showed that women with higher levels of FoC had more unfavorable birth outcomes, such as higher rates of CS and neonatal admission to SCN/NICU, the differences were not statistically significant. This might have been due to the 8% lost-to-follow-up and availability of birth outcomes for only 195 women out of 212 participants, affecting the study power for birth outcomes. Therefore, further exploration is needed to determine the clinical significance of these findings. Nevertheless, in real practice, clinicians may be guided by more than just the P value. They need to exercise their clinical judgment based on the possibility of unfavorable outcomes in these women, such as the progress of labour.

The lower rates of tears, episiotomy and epidural/spinal use during a vaginal birth in women with high levels of FoC may be justified by the greater rate of caesarean section in these women compared to those with low-moderate levels of FoC. Furthermore, shorter lengths of postnatal hospital stay in women with higher levels of FoC could have been due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, causing fear of prolonged hospital stays and consequent contraction of the virus.

While previous research on FoC has predominately focused on nulliparous women, our specific focus on multiparous women contributes to the expanding body of knowledge in this underexplored population. The use of comprehensive online questionnaires that examined several facets of FoC is one of the present study's strengths. In several earlier studies, W-DEQ was employed as the only well-used and well-validated measuring instrument for FoC. In comparison, we adopted W-DEQ as our primary instrument for assessing the prevalence of FoC, with FoBS serving as a supporting and confirmatory measure. Furthermore, our study cohort was ethnically diverse compared to earlier studies, allowing us to investigate novel demographic risk factors associated with FoC. In addition, parity is a crucial predictor of FoC, and we eliminated nulliparous women from our study to exclude the influence of being a first-time mother on the prevalence of FoC among our participants.

Nonetheless, there are several limits to our research. In order to assess relationship satisfaction and sexual dysfunction during pregnancy, the RAS and FSFI tools were added to the questionnaires. These questions, however, were not com

Our study was conducted in a public hospital in western Sydney and did not include data from private hospitals or other public hospitals across the state of New South Wales or Australia. Future research may examine the prevalence of FoC among women in both public and private settings. Additionally, in current study, we did not recruit participants from multiple locations, therefore, our study sample was not representative of Australian population. We excluded women with high-risk pregnancies or women diagnosed with mental health concerns such as depression or anxiety, and we did not compare our sample characteristics to the characteristics of the population of birthing women in our hospital. As such, our findings may not be generalized to the population of birthing people in Australia.

The current study provides essential evidence for the development of prenatal education program in maternity facilities. With the calculated prevalence of FoC in Australian multiparous women in this study, hospitals can be better equipped to provide customized maternity care. It is crucial for healthcare providers to understand women's pregnancy journeys, particularly for multiparous women who have had negative or traumatic childbirth experiences. To empower and support women through these program, their unique needs must be recognized, and assistance in coping with fear and anxiety must be made available in a way that contributes to a positive pregnancy experience and birth outcome[57].

Previous studies in Western countries have shown that the majority of maternity clinics do not provide special services or counselling support for FoC[58]. This highlights the need to develop standardized pathways of care and interventions for women with FoC. Also, risk factors of FoC, including women’s socio-cultural background, general health, psychological status, level of support and prior birth experience, need to be taken into consideration by clinicians when provi

While pregnancy and childbirth are unique experiences for women, those with a history of childhood sexual abuse may experience more challenges during this life-changing period. The association between childhood sexual abuse and negative maternal and neonatal outcomes necessitates the need for accurate assessment and screening to detect those who are at risk and provide them with trauma-sensitive care and consideration[54].

It is recommended to conduct a longitudinal study to observe the changes in FoC with pregnancy progression and its long-term impact on the perinatal outcomes after birth. Future studies also need to compare the FoC levels between low-risk and high-risk pregnant women, and explore the unique needs and intervention strategies of different risk groups. In addition, further studies are required to explore the differences in the incidence of FoC between public and private healthcare environments, and understand the impact of different healthcare systems on women's childbirth experience.

Using the W-DEQ, we discovered that 24% of Australian multiparous women experienced high FoC, and 7% experienced severe FoC. We discovered that a ≤ $100000 family income, no alcohol intake, pre-existing health problems, previous caesarean section, past neutral/traumatic childbirth experience, and severe to extremely severe anxiety were all related to worsened FoC. Furthermore, women who had anxiety, experiences of previous traumatic childbirth, a history of child

We appreciate the in-kind support we received from the Department of Women’s and Newborn Health at Westmead hospital to conduct this study. We would like to thank the managers and clinicians at the antenatal clinic at Westmead hospital for their valuable cooperation and support during data collection stage.

| 1. | Nordeng H, Hansen C, Garthus-Niegel S, Eberhard-Gran M. Fear of childbirth, mental health, and medication use during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Gissler M, Halmesmäki E, Saisto T. Mental health problems common in women with fear of childbirth. BJOG. 2011;118:1104-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Otley H. Fear of childbirth: Understanding the causes, impact and treatment. Br J Midwifery. 2011;19:215-220. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nilsson C, Hessman E, Sjöblom H, Dencker A, Jangsten E, Mollberg M, Patel H, Sparud-Lundin C, Wigert H, Begley C. Definitions, measurements and prevalence of fear of childbirth: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | O'Connell MA, Leahy-Warren P, Khashan AS, Kenny LC, O'Neill SM. Worldwide prevalence of tocophobia in pregnant women: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:907-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Phunyammalee M, Buayaem T, Boriboonhirunsarn D. Fear of childbirth and associated factors among low-risk pregnant women. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;39:763-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhou X, Liu H, Li X, Zhang S. Fear of Childbirth and Associated Risk Factors in Healthy Pregnant Women in Northwest of China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:731-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fairbrother N, Albert A, Collardeau F, Keeney C. The Childbirth Fear Questionnaire and the Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire as Screening Tools for Specific Phobia, Fear of Childbirth. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Toohill J, Fenwick J, Gamble J, Creedy DK. Prevalence of childbirth fear in an Australian sample of pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Räisänen S, Lehto SM, Nielsen HS, Gissler M, Kramer MR, Heinonen S. Fear of childbirth in nulliparous and multiparous women: a population-based analysis of all singleton births in Finland in 1997-2010. BJOG. 2014;121:965-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dencker A, Nilsson C, Begley C, Jangsten E, Mollberg M, Patel H, Wigert H, Hessman E, Sjöblom H, Sparud-Lundin C. Causes and outcomes in studies of fear of childbirth: A systematic review. Women Birth. 2019;32:99-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fenwick J, Gamble J, Nathan E, Bayes S, Hauck Y. Pre- and postpartum levels of childbirth fear and the relationship to birth outcomes in a cohort of Australian women. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:667-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ryding EL, Wirfelt E, Wängborg IB, Sjögren B, Edman G. Personality and fear of childbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:814-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nilsson C, Lundgren I, Karlström A, Hildingsson I. Self reported fear of childbirth and its association with women's birth experience and mode of delivery: a longitudinal population-based study. Women Birth. 2012;25:114-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sydsjö G, Sydsjö A, Gunnervik C, Bladh M, Josefsson A. Obstetric outcome for women who received individualized treatment for fear of childbirth during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91:44-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Halmesmäki E, Saisto T. Fear of childbirth according to parity, gestational age, and obstetric history. BJOG. 2009;116:67-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kubik-machura DM, Kuć AJ, Kościelecka KE, Męcik-kronenberg T. Tocophobia–Short review of current literature. Emerg Med Serv. 2022;9:237-244. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Souza JP, Zhang J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 160.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 19. | Seijmonsbergen-Schermers AE, van den Akker T, Rydahl E, Beeckman K, Bogaerts A, Binfa L, Frith L, Gross MM, Misselwitz B, Hálfdánsdóttir B, Daly D, Corcoran P, Calleja-Agius J, Calleja N, Gatt M, Vika Nilsen AB, Declercq E, Gissler M, Heino A, Lindgren H, de Jonge A. Variations in use of childbirth interventions in 13 high-income countries: A multinational cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2020;17:e1003103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Adams SS, Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A. Fear of childbirth and duration of labour: a study of 2206 women with intended vaginal delivery. BJOG. 2012;119:1238-1246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lukasse M, Schei B, Ryding EL; Bidens Study Group. Prevalence and associated factors of fear of childbirth in six European countries. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2014;5:99-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Laursen M, Hedegaard M, Johansen C; Danish National Birth Cohort. Fear of childbirth: predictors and temporal changes among nulliparous women in the Danish National Birth Cohort. BJOG. 2008;115:354-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Haines H, Pallant JF, Karlström A, Hildingsson I. Cross-cultural comparison of levels of childbirth-related fear in an Australian and Swedish sample. Midwifery. 2011;27:560-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kabukcu C, Sert C, Gunes C, Akyol HH, Tipirdamaz M. Predictors of prenatal distress and fear of childbirth among nulliparous and parous women. Niger J Clin Pract. 2019;22:1635-1643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Söderquist J, Wijma B, Wijma K. The longitudinal course of post-traumatic stress after childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;27:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ryding EL, Wijma B, Wijma K, Rydhström H. Fear of childbirth during pregnancy may increase the risk of emergency cesarean section. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1998;77:542-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bedaso A, Adams J, Peng W, Sibbritt D. The relationship between social support and mental health problems during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2021;18:162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Harrison S, Pilkington V, Li Y, Quigley MA, Alderdice F. Disparities in who is asked about their perinatal mental health: an analysis of cross-sectional data from consecutive national maternity surveys. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Webb R, Uddin N, Ford E, Easter A, Shakespeare J, Roberts N, Alderdice F, Coates R, Hogg S, Cheyne H, Ayers S; MATRIx study team. Barriers and facilitators to implementing perinatal mental health care in health and social care settings: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:521-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Poo ZX, Quah PL, Chen H, Wright A, Teoh TG, Tan LK, Tan KH. Knowledge, Attitude and Perceptions Around Perinatal Mental Health Among Doctors in an Obstetrics and Gynaecology Academic Department in Singapore. Cureus. 2023;15:e38906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wilkinson E. Psychiatrists urge NHS England to improve data on antenatal mental health screening. BMJ. 2023;381:1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Keedle H, Lockwood R, Keedle W, Susic D, Dahlen HG. What women want if they were to have another baby: the Australian Birth Experience Study (BESt) cross-sectional national survey. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e071582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Boatin AA, Schlotheuber A, Betran AP, Moller AB, Barros AJD, Boerma T, Torloni MR, Victora CG, Hosseinpoor AR. Within country inequalities in caesarean section rates: observational study of 72 low and middle income countries. BMJ. 2018;360:k55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Khajehei M, Swain JA, Li R. Fear of childbirth in nulliparous and multiparous women in Australia. Br J Midwifery. 2023;31:686-694. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Haines CJ, Shan YO, Kuen CL, Leung DH, Chung TK, Chin R. Sexual behavior in pregnancy among Hong Kong Chinese women. J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:299-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Haines HM, Pallant JF, Fenwick J, Gamble J, Creedy DK, Toohill J, Hildingsson I. Identifying women who are afraid of giving birth: A comparison of the fear of birth scale with the WDEQ-A in a large Australian cohort. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2015;6:204-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hildingsson I, Rubertsson C, Karlström A, Haines H. Exploring the Fear of Birth Scale in a mixed population of women of childbearing age-A Swedish pilot study. Women Birth. 2018;31:407-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Stoll K, Hauck Y, Downe S, Edmonds J, Gross MM, Malott A, McNiven P, Swift E, Thomson G, Hall WA. Cross-cultural development and psychometric evaluation of a measure to assess fear of childbirth prior to pregnancy. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2016;8:49-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Osman A, Wong JL, Bagge CL, Freedenthal S, Gutierrez PM, Lozano G. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21): further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68:1322-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 577] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Mitchell MC, Burns NR, Dorstyn DS. Screening for depression and anxiety in spinal cord injury with DASS-21. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:547-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Madhavanprabhakaran GK, D’souza MS, Nairy KS. Prevalence of pregnancy anxiety and associated factors. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2015;3:1-7. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Faisal-Cury A, Rossi Menezes P. Prevalence of anxiety and depression during pregnancy in a private setting sample. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10:25-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Bibi A, Lin M, Zhang XC, Margraf J. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21) across cultures. Int J Psychol. 2020;55:916-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Burri A, Cherkas L, Spector T. Replication of psychometric properties of the FSFI and validation of a modified version (FSFI-LL) assessing lifelong sexual function in an unselected sample of females. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3929-3939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Meston CM. Validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in women with female orgasmic disorder and in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29:39-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 385] [Cited by in RCA: 420] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, D'Agostino R Jr. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3880] [Cited by in RCA: 4313] [Article Influence: 172.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:1-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1443] [Cited by in RCA: 1643] [Article Influence: 82.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Vaughn M, Baier MEM. Reliability and validity of the relationship assessment scale. The Am J of Fam Ther. 1999;27:137-147. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 49. | Hendrick SS. A Generic Measure of Relationship Satisfaction. J Marriage Fam. 1988;50:93. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 50. | Berthelot N, Lemieux R, Garon-Bissonnette J, Drouin-Maziade C, Martel É, Maziade M. Uptrend in distress and psychiatric symptomatology in pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:848-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Wu Y, Zhang C, Liu H, Duan C, Li C, Fan J, Li H, Chen L, Xu H, Li X, Guo Y, Wang Y, Li X, Li J, Zhang T, You Y, Li H, Yang S, Tao X, Xu Y, Lao H, Wen M, Zhou Y, Wang J, Chen Y, Meng D, Zhai J, Ye Y, Zhong Q, Yang X, Zhang D, Zhang J, Wu X, Chen W, Dennis CL, Huang HF. Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:240.e1-240.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 71.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Silva MMJ, Nogueira DA, Clapis MJ, Leite EPRC. Anxiety in pregnancy: prevalence and associated factors. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2017;51:e03253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Størksen HT, Garthus-Niegel S, Adams SS, Vangen S, Eberhard-Gran M. Fear of childbirth and elective caesarean section: a population-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Brunton R, Dryer R. Child Sexual Abuse and Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;111:104802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Hall WA, Hauck YL, Carty EM, Hutton EK, Fenwick J, Stoll K. Childbirth fear, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep deprivation in pregnant women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38:567-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Kranenburg L, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, Stramrood C. Traumatic Childbirth Experience and Childbirth-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): A Contemporary Overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Webb R, Bond R, Romero-gonzalez B, Mycroft R, Ayers S. Interventions to treat fear of childbirth in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2021;51:1964-1977. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Vaajala M, Liukkonen R, Ponkilainen V, Mattila VM, Kekki M, Kuitunen I. Birth rate among women with fear of childbirth: a nationwide register-based cohort study in Finland. Ann Epidemiol. 2023;79:44-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |