Copyright

©2010 Baishideng Publishing Group Co.

World J Biol Chem. May 26, 2010; 1(5): 109-132

Published online May 26, 2010. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v1.i5.109

Published online May 26, 2010. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v1.i5.109

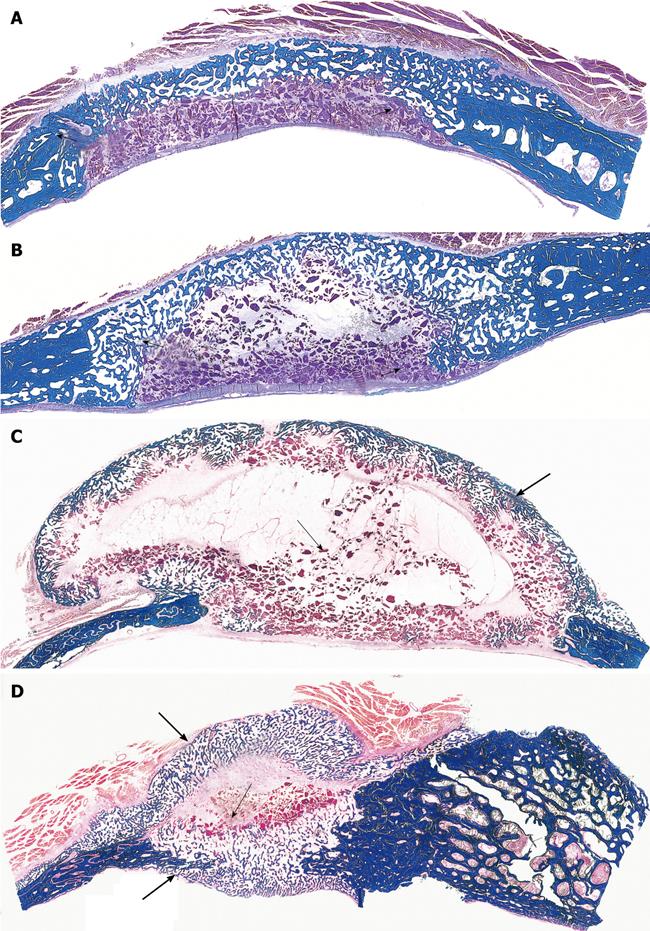

Figure 6 Limited induction of bone formation by the recombinant hTGF-β3 and hTGF-β2 when implanted in calvarial defects of P.

ursinus but induction of massive ossicles after binary applications of recombinant hOP-1 with relatively low doses of platelet-derived pTGF-β1. A, B: Morphology of calvarial regeneration and induction of bone formation after application of 125 μg hTGF-β3 and 100 μg hTGF-β2, respectively, on day 90 after calvarial implantation. Note the induction of bone formation across the defects on the pericranial aspect only with limited if any bone formation at the endocranial dural aspect of both specimens. Short arrows point to the inhibition of bone formation within the fibrogenic collagenous matrix facing the newly formed bone originating pericranially and endocranially at the defect margins; C, D: Synergistic induction of bone formation upon implantation of binary application of 100 μg hOP-1 with 5 μg of porcine platelet-derived TGF-β1 (C) and 15 μg pTGF-β1 (D) 30 d after calvarial implantation. Prominent pericranial osteogenesis displacing the temporalis muscle; note the pericranial and endocranial osteogenetic fronts of mineralized newly formed bone (thick long arrows) surrounding scattered remnants of the collagenous matrix as carrier (thin long arrows). Undecalcified sections cut at 6 μm stained free-floating with a modified Goldner’s trichrome.

- Citation: Ripamonti U. Soluble and insoluble signals sculpt osteogenesis in angiogenesis. World J Biol Chem 2010; 1(5): 109-132

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8454/full/v1/i5/109.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4331/wjbc.v1.i5.109