Published online Nov 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i11.2639

Peer-review started: July 27, 2023

First decision: September 11, 2023

Revised: September 20, 2023

Accepted: September 27, 2023

Article in press: September 27, 2023

Published online: November 27, 2023

Isolated gallbladder injury (GI) (IGI) directly induced by abdominal trauma is rare. Symptoms, indications, and imaging examinations of IGI are frequently non-specific, posing tremendous diagnostic challenges, which are simple to overlook and may have severe implications. Improving doctors' understanding of gallbladder injury (GI) facilitates early detection and decreases the likelihood of severe consequences, including death.

We report a case of IGI caused by blunt violence (after falling from three meters with the umbilicus as the stress point) and performed laparoscopic repair of the gallbladder rupture, which helps clinicians understand IGI and reduce the severe consequences of delayed diagnosis. Through extensive medical history and dynamic abdominal ultrasound evaluation, doctors can identify GI early and begin surgery, thereby decreasing the devastating repercussions of delayed diagnosis.

This article aims to improve clinicians' understanding of IGI and propose a method for the diagnosis and treatment of GI.

Core Tip: Blunt-force closed abdominal injury is a prevalent clinical condition. Gallbladder injury directly caused by blunt violence in the abdomen is rare, and isolated traumatic gallbladder injury is even rarer. No literature study has determined the likelihood of solitary traumatic gallbladder injury in closed abdominal injury. Therefore, in the diagnosis and treatment of closed abdominal trauma, gallbladder injury is easy to be ignored by clinicians because gallbladder injury is rare. If undiagnosed and untreated, it can cause significant consequences, including death.

- Citation: Liu DL, Pan JY, Huang TC, Li CZ, Feng WD, Wang GX. Isolated traumatic gallbladder injury: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(11): 2639-2645

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i11/2639.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i11.2639

Here, we reported a gallbladder wall rupture due to blunt violence on the abdomen. After surgery, the patient had isolated gallbladder injury (GI) (IGI) but no other organ damage. Finally, the patient underwent gallbladder repair and was discharged on the 7th day after the operation. This research aims to improve doctors' awareness of GI in diagnosing and treating closed abdominal trauma and present diagnostic thinking to improve the early detection rate and lower the risk of serious consequences, including death.

Abdominal pain for 1 h due to trauma.

A 48-year-old man fell from a 3-meter building, initially falling with his umbilicus towards the floor. The umbilicus was bluntly hit, which caused significant abdominal pain. The patient was admitted to our hospital for emergency treatment. The patient reported severe abdominal pain radiating to the right shoulder, along with dysuria, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, palpitations, chest tightness, and shortness of breath, among other symptoms.

History of appendectomies.

No special personal history, and family history.

A clear mind was observed, and vital signs were (body temperature: 36.6 °C; heart rate: 51 beats/min; respiration: 22 beats/min; blood pressure: 141/71 mmHg). No abnormalities were observed in the heart or the lungs. The abdominal muscles were slightly tense, the abdomen was tender, and rebound pain was absent. There were no discernible distinctions in the rest.

No evident abnormality was found in the routine blood test, biochemistry, coagulation function, amylase and creatinine of ascites.

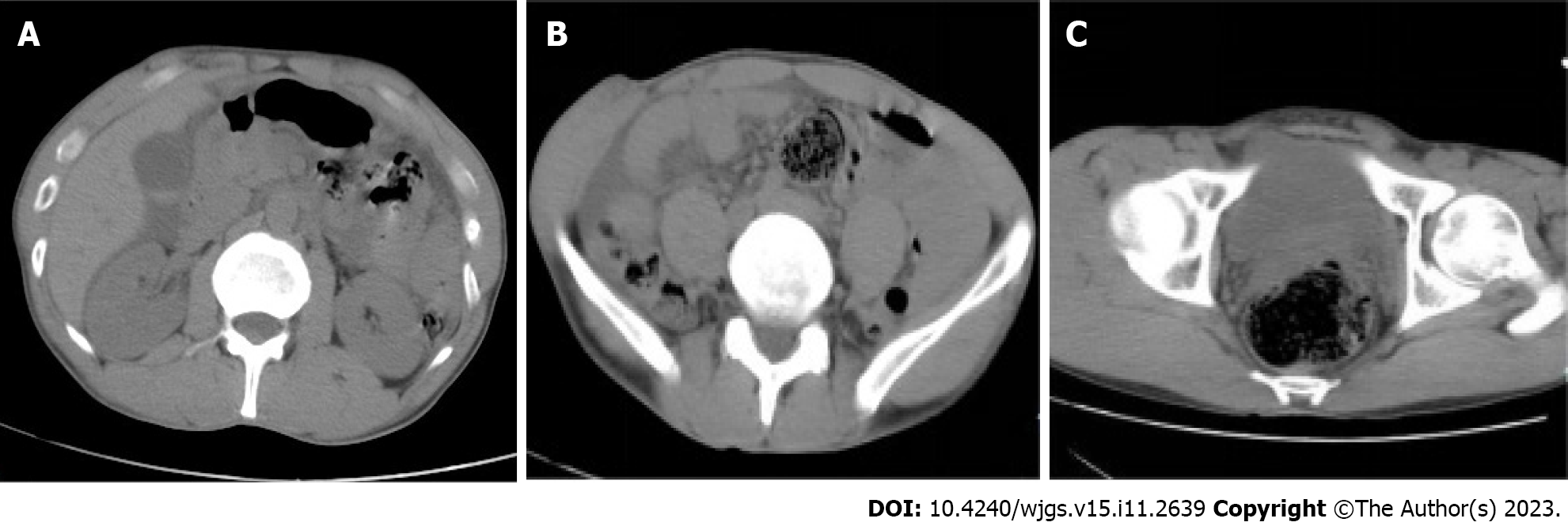

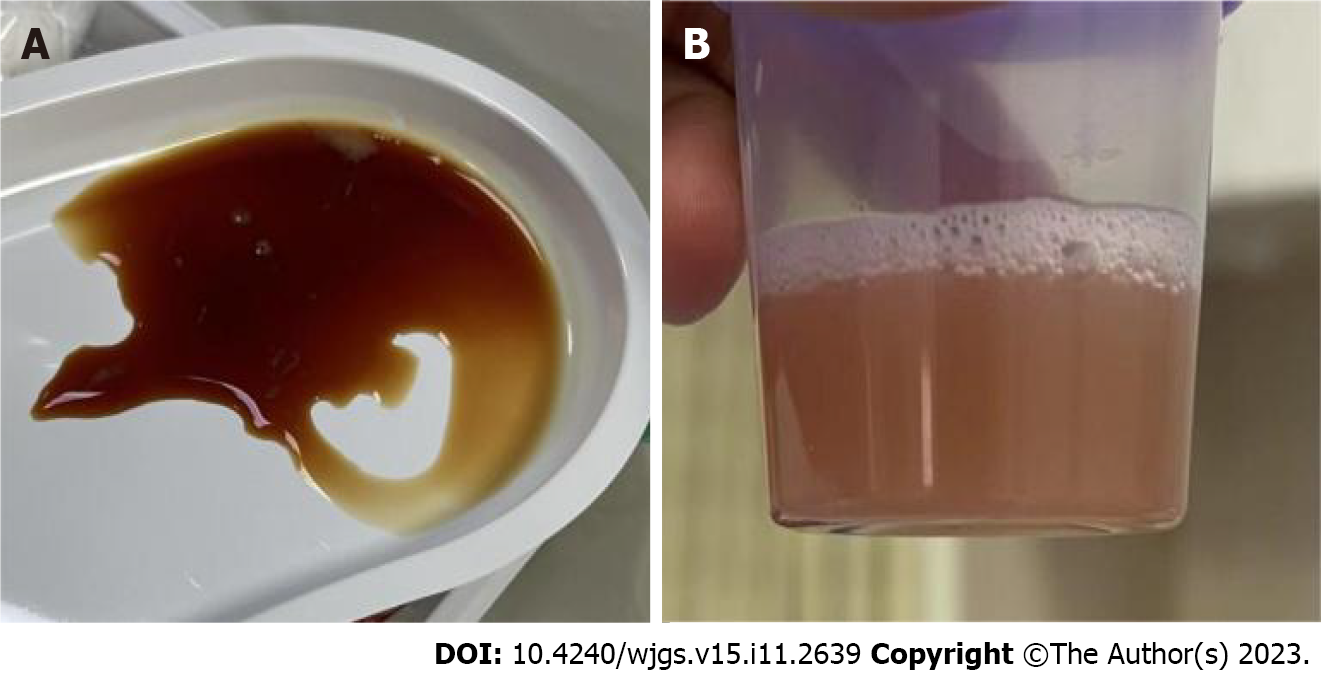

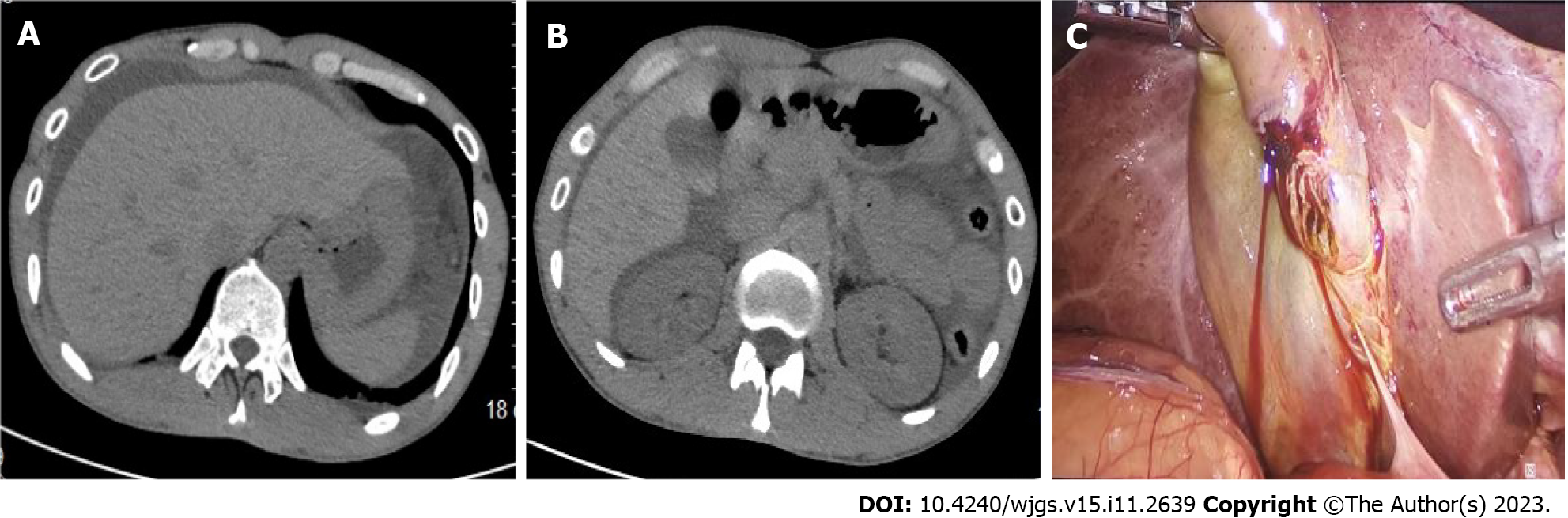

During the initial treatment, the team conducted an abdominal color ultrasound examination of the patient, suggesting a lamellar middle and low echo in the gallbladder cavity cholestasis? or silty stone (Figure 1)? For postprandial gallbladder status, the gallbladder wall thickens, sound transmission is good, and there is a low and medium echo in the cavity. The boundary was unclear, and the shape was uneven. No obvious abnormality was observed in the rest. Over an hour after the injury, the patient's abdomen pain worsened. An abdominal color ultrasound examination was performed again, indicating ascites. Simultaneously, a computed tomography (CT) examination showed a small, high-density area in the gallbladder and cholestasis. The examination indicates a possible stone, alongside observed rectal dilatation and fecal accumulation. There is also evidence of abdominal and pelvic effusion. It is recommended that further examination be conducted (Figure 2). An abdominal anteroposterior radiograph displays that a part of the intestine in the middle abdomen is dilated (Figure 3). A diagnostic abdominal puncture was performed two hours after the injury to clarify ascites. Reddish abdominal ascites were extracted through abdominal paracentesis (Figure 4). Five hours after the injury, the abdominal CT showed cholestasis and a slightly high-density gallbladder stone. Again, the abdominal and pelvic effusions increased (Figure 5A and B).

Through laparoscopic examination, we ultimately determined that the patient had isolated traumatic gallbladder injury.

Although clinical symptoms, signs, and imaging investigations have not yet revealed the site of an abdominal injury, changes in abdominal symptoms and signs and the increase in ascites suggested by CT strongly indicate abdominal organ injury. The disease progressed rapidly; thus, performing an enhanced CT examination was impossible. Finally, the patients and their families agreed to undergo emergency surgical exploration. Laparoscopic exploration was preferred. We made an arc incision on the umbilicus and placed a 10 mm trocar as the observation hole. Through laparoscopic exploration, we can observe extensive fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity, presenting about 1000 mL of bile-like fluid, no bruises on the liver and spleen, the gallbladder was approximately 8 cm × 6 cm × 3 cm in size, and there was a rupture on the anterior wall of the gallbladder, approximately 4 cm × 1 cm (Figure 5C).

There were no apparent active bleeding symptoms; however, blood clots and bile were visible, and no evident bruises were observed on the first hepatic hilus. In the right lower abdomen, parts of the omentum and intestines were linked to the anterior abdominal wall. Accordingly, we performed laparoscopic repair of the gallbladder perforation and continuously sutured the gallbladder contusion with the absorbable barbed suture lines. The suture was strengthened using a seromuscular layer to prevent postoperative bile leakage. Although the gallbladder was repaired laparoscopically, superficial GI caused by clinical trauma is infrequent. It was necessary to further explore the damage to the viscera around the gallbladder, specifically the injury of the retroperitoneal intestinal duct, and the patient was transferred for open exploration. By taking the median abdominal incision, the transverse colon mesentery edema is prominent, and hematoma formation can be seen locally, but the blood supply and peristalsis of the intestine are regular. The peritoneum was opened around the liver curvature of the colon and the lateral part of the descending duodenum to observe substantial tissue edema, discoloration, and hematoma development. The visible descending duodenum, stomach, pancreas, duodenal bulb, small intestine, large intestine, and mesentery were not obvious contusions or lacerations. After the surgical investigation, three drainage tubes were inserted into the right lower liver, appropriate peritoneal space, and pelvic cavity to drain the ascites and prevent serious consequences. After the procedure, the patient was transferred to the hepatobiliary surgery department.

After the operation, the patient was in good condition, and the symptoms improved significantly. The patient reported little incision site pain on the first day after the procedure, but no further noticeable discomfort was noted. On the second postoperative day, the patient consumed a small amount of liquid diet after anal exhaust. One week after the process, the abdominal CT was rechecked. CT results did not reveal any problems. The ascites in the abdominal cavity were absorbed. The patient recovered well postoperatively. The symptoms, signs, and infections were controlled. There were no postoperative complications, like "postoperative biliary leakage and intestinal obstruction", thus he was discharged. During the regular follow-up process of six months after surgery, the patient showed no abnormalities.

Closed abdominal injury caused by blunt violence is among the common clinical diseases. Most closed abdominal injuries are caused by blunt violence, which directly affects the abdomen. Injuries to the liver, spleen, and small intestine are the most common types of closed abdominal injuries[1]. Clinicians focus on the liver, spleen, small intestine, and other injuries when diagnosing and treating blunt closed abdominal injuries. GI is often neglected because it is rare and can easily cause serious complications, including death[2,3]. No literature study has determined the likelihood of solitary traumatic gallbladder injury in closed abdominal injury[4].

Thin-walled and dilated gallbladders, long-term alcohol consumption, and liver cirrhosis are major research causes[5-8].

This case was caused by blunt violence in the abdomen during fasting, resulting in gallbladder rupture. The impact point is at the umbilicus, and non-blunt violence immediately affects the right upper abdomen, which has not been documented in earlier reports. Under fasting conditions, a large amount of bile secreted by the liver is stored in the gallbladder, which is relatively complete. When the abdomen is subjected to blunt violence, the pressure in the bile duct rises sharply, causing gallbladder rupture, which is among the critical factors causing GI in this patient, consistent with the common inducing factors of GI mentioned by Abouelazayem et al[5]. By exploring the abdomen, we also found that the tissues adjacent to the gallbladder, mesentery of the colon, lateral peritoneum, and posterior peritoneum also had contusion manifestations such as tissue edema and hematoma formation. Therefore, the gallbladder and adjacent tissues at this time should be hedged injuries formed after the impact. In conclusion, external forces on the larger gallbladder during fasting and the sudden increase in biliary tract pressure may have caused the patient's gallbladder to rupture.

Reviewing previous literature reports, the early symptoms and signs in isolated patients with GI are non-specific, as in this patient. Due to the non-specific symptoms and signs of the disease and the absence of obvious abnormalities on the patient's abdominal CT plain scan, we decided to continue observing the changes in the patient's symptoms and signs and did not directly perform enhanced CT in the early stages of diagnosis, which is one of the reasons why enhanced CT examination was not performed. If the patient's symptoms and signs worsened, we rechecked color ultrasound and CT scans, carefully read the examination images and reports, and still did not observe any obvious organ damage. Compared with the results of the two examinations, no significant abnormal changes were observed. Meanwhile, considering the high cost of enhanced CT and the absence of obvious organ damage in the two examination results, we did not choose to perform enhanced CT examination during the relatively stable period of the condition, which is also one of the reasons why patients did not undergo enhanced CT examination. However, in this case, the injured part of the patient was not in the right upper abdomen. Abdominal X-ray, CT, and ultrasound did not show gallbladder rupture, which has rarely been reported[9,10]. Therefore, in diagnosing and treating these diseases, we did not consider the possibility of GI. During disease progression, considering the specific impact site of the patient's abdomen, abdominal pain, difficulty in urinating, and the increase in ascites volume indicated by imaging examinations, we not only considered the damage to organs such as the liver, spleen, and small intestine but also the possibility of bladder rupture. To clarify the nature and source of ascites, we chose CT-guided abdominal puncture, and the ascites obtained from the puncture were sent for amylase and creatinine examination. No obvious abnormalities were found, so the possibility of rupture of the liver, spleen, small intestine, and bladder was preliminarily ruled out. Although we have actively conducted diagnostic puncture of ascites, the bile-like fluid was not extracted, which may be related to the short time of injury and the formation of a package around the omentum after GI, resulting in the bile not spreading to the whole abdominal cavity. Therefore, this poses a significant challenge for diagnosis.

Color Doppler ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are important examinations for diagnosing abdominal injuries, including GI.

Abdominal ultrasonography showed thickening of the gallbladder and gallbladder wall after a meal. Combined with the patient's history of fasting, it can highly suspect the possibility of GI[8,11,12]. Due to its convenience and fast, continuous dynamic observation of gallbladder size, wall thickness, and cavity contents, ultrasonography has become the preferred choice for identification of gallbladder illness despite its low sensitivity, specificity, and difficulty in locating the injury. In patients with negative CT findings, repeated ultrasound re-examinations often have unintended discoveries[11]. Therefore, dynamic ultrasound examination is critical.

CT has been proven to be another essential examination method for detecting GI[13]. Regular CT plain scans can determine whether the abdominal organs are damaged promptly. According to relevant literature reports, enhanced CT is one of the most effective tools for identifying GI[14]. Enhanced CT can help determine the diseases of abdominal organs, especially gallbladder stones and intracavitary bleeding, which are difficult to identify on plain scans. This is an essential examination for diagnosing GI. MRI can effectively identify soft tissue injuries[15] but is unsuitable for patients with acute abdomen because of its long examination time[16].

According to Reitz et al[17], there are methods for using retrograde cholangiography to determine the specific location of GI. However, this method is based on the premise that no obvious damage site is detected under laparoscopy, which is not consistent with our medical records.

Accordingly, we believe that to diagnose GI, we must first understand the medical history (the origin of the injury, the process of occurrence—if it directly affects the right upper abdomen, whether it is empty is vital for closed abdominal injury). Second, ultrasound examination and conventional abdominal CT are necessary, and even enhanced CT examination is required if conditions permit. In this case, CT cannot indicate the source of ascites, but it still had a unique diagnostic value. Comparing new and old images shows that ascites increase, which helps clinicians choose the best treatment regimen.

The patient's symptoms and signs are supposed to continue progressing, as in this case report. In this case, the patient moves from non-specific single abdominal pain symptoms to obvious peritoneal irritation signs, and we recommend that a diagnostic laparoscopy be performed as soon as possible. Laparoscopy can reduce organ damage, serious consequences, and even death by rapidly locating the injury site. It is also one of the methods of less damage in invasive examinations. Many recent studies have reported that laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the first-line treatment for gallbladder trauma[1,18]. However, considering that the patient had no history of gallstones, and the previous routine physical examination did not indicate gallbladder lesions, the chief surgeon team finally decided to perform laparoscopic gallbladder rupture repair with the absorbable barbed suture lines and reinforcement suture of the seromuscular layer. We recommend this surgical suture approach to prevent postoperative biliary leakage.

Moreover, in this case, although the gallbladder was repaired under laparoscopy, considering the need for further exploration of other abdominal organs, mesentery, and retroperitoneal injuries and determining whether further intervention is needed, we chose to open the investigation. According to our hospital's experience in treating closed abdominal injuries, laparoscopic exploration can miss tiny intestinal and retroperitoneal injuries. This has also been mentioned in previous literature[19], and in this case, blunt violence acts on the umbilicus, resulting in IGI, which is extremely rare. We suspected damage to other abdominal organs; thus, we chose to perform open exploration. The patient recovered well postoperatively during the regular return visit, and no related complications were found.

GI caused by blunt violence is rare, and IGI is even rarer. Symptoms, indications, and imaging examinations of solitary GI are frequently non-specific, pose tremendous diagnostic challenges, are simple to overlook, and may have severe implications. This article aims to improve clinicians' understanding of IGI and propose a method for the diagnosis and treatment of GI. Through extensive medical history and dynamic abdominal ultrasound evaluation, doctors can immediately identify GI and begin surgery, thereby decreasing the devastating repercussions of delayed diagnosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gad EH, Egypt; Hatipoglu S, Turkey S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu RR

| 1. | Gäble A, Mück F, Mühlmann M, Wirth S. Acute abdominal trauma. Radiologe. 2019;59:139-145. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Khan MR, Begum S. Isolated gallbladder injury from blunt abdominal trauma: A rare co-incidence. J Pak Med Assoc. 2020;70(Suppl 1):S95-S98. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Zellweger R, Navsaria PH, Hess F, Omoshoro-Jones J, Kahn D, Nicol AJ. Gall bladder injuries as part of the spectrum of civilian abdominal trauma in South Africa. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:559-561. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Salzman S, Lutfi R, Fishman D, Doherty J, Merlotti G. Traumatic rupture of the gallbladder. J Trauma. 2006;61:454-456. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abouelazayem M, Belchita R, Tsironis D. Isolated Gallbladder Injury Secondary to Blunt Abdominal Trauma. Cureus. 2021;13:e15337. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Philipoff AC, Lumsdaine W, Weber DG. Traumatic gallbladder rupture: a patient with multiple risk factors. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pham HD, Nguyen TC, Huynh QH. Diagnostic imaging in a patient with an isolated blunt traumatic gallbladder injury. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16:2557-2563. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Testini V, Tupputi U, Rutigliano C, Guerra FS, Mannatrizio D, Bellitti R, Scarabino T, Guglielmi G. A rare case of isolated gallbladder rupture following blunt abdominal trauma. Acta Biomed. 2023;94:e2023207. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tudyka V, Toebosch S, Zuidema W. Isolated Gallbladder Injury after Blunt Abdominal Trauma: a Case Report and Review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2008;34:320. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Egawa N, Ueda J, Hiraki M, Ide T, Inoue S, Sakamoto Y, Noshiro H. Traumatic Gallbladder Rupture Treated by Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2016;10:212-217. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim PN, Lee KS, Kim IY, Bae WK, Lee BH. Gallbladder perforation: comparison of US findings with CT. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:239-242. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Siskind BN, Hawkins HB, Cinti DC, Zeman RK, Burrell MI. Gallbladder perforation. An imaging analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;9:670-678. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Van Kerschaver O, De Witte B, Kint M, Vereecken L. An unusual case of blunt abdominal trauma: A bleeding and ruptured gall-bladder managed by laparoscopy. Acta Chir Belg. 2006;106:417-419. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Birn J, Jung M, Dearing M. Isolated gallbladder injury in a case of blunt abdominal trauma. J Radiol Case Rep. 2012;6:25-30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin BC, Chen RJ, Fang JF. Isolated blunt traumatic rupture of gallbladder. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:231-233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wong YC, Wang LJ, Chen CJ. MRI of an isolated traumatic perforation of the gallbladder. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:657-658. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Reitz MM, Araújo JM, de Souza GHN, Gagliardi DP, de Toledo FVT, Ribeiro Júnior MAF. Choleperitoneum secondary to isolated subserosal gallbladder injury due to blunt abdominal trauma - A case report. Trauma Case Rep. 2022;41:100674. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | 60th birthday of Prof. P. Málek, M.D.D.Sc. member correspondent of the CSAS (Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences). Cas Lek Cesk. 1975;114:447-448. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Stahl WM. A critical evaluation of laparoscopy in penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1993;34:822-7; discussion 827. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 184] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |