INTRODUCTION

Ghrelin, a peptide hormone that serves as the endogenous ligand of the growth hormone secretagogue receptor, is secreted mainly by P/D1 cells lining the fundus of the human stomach, and the epsilon cells of the pancreas that stimulate hunger[1]. Ghrelin is also secreted from the small intestine and the colon. It is expressed in the hypothalamus, pituitary, and several peripheral tissues suggesting that it could have diverse physiological functions[2-5]. Ghrelin regulates growth hormone secretion, and plays an important role in the regulation of appetite, energy balance and glucose homeostasis. It regulates gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and immune functions, and bone physiology[6-12]. Ghrelin levels increase before meals, decrease after meals, and serve as the counterpart of leptin, which induces satiation when present at higher levels. Bariatric procedures lead to a reduction in the amount of ghrelin produced, which causes the satiation that could explain the weight loss occurring after gastric bypass surgery. Receptors for ghrelin are expressed by the neurons in the arcuate nucleus and the ventromedial hypothalamus[13] that have a regulatory role in insulin secretion and participate in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus, thus implying that ghrelin has a role in insulin resistance. The ghrelin receptor is a G protein-coupled receptor. Ghrelin is essential for cognitive adaptation to changing environments and the process of learning[14], and activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)[15,16]. Obestatin, which is derived from the same gene as ghrelin, has opposite actions to that of ghrelin on energy homeostasis and gastrointestinal function, thus adding complexity to the role of ghrelin in various physiological and pathological situations[17].

GENERAL PROPERTIES OF GHRELIN

Ghrelin exists in an endocrinological inactive (pure peptide) and an active (octanoylated) form. Side chains other than octanoyl have also been reported.

Ghrelin and synthetic ghrelin mimetics (the growth hormone secretagogues) increase food intake and increase fat mass[18,19] by an action exerted at the level of the hypothalamus. Ghrelin and other growth hormone secretagogues activate cells in the arcuate nucleus[20,21] that include the orexigenic neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons[22]. The ghrelin-responsiveness of these neurones is both leptin- and insulin-sensitive[23]. Ghrelin also activates the mesolimbic cholinergic-dopaminergic reward link, a circuit that communicates the hedonic and reinforcing aspects of natural rewards, such as food, as well as those of addictive drugs, such as ethanol[24-28].

GHRELIN IN LUNG DEVELOPMENT AND LUNG INJURY DUE TO SEPSIS

In fetuses, ghrelin is produced by the lungs and promotes their growth and development[29]. Ghrelin protein has been found in the endocrine cells of the fetal lung in decreasing amounts from the embryonic to late fetal periods. Its expression was shown to be maintained in newborns and children under 2 years, but it was found to be virtually absent in older individuals. Scattered positive cells have also been also found in the trachea and the esophagus. Ghrelin mRNA has been detected in adult lung tissue, indicating the existence of local autocrine circuits[30]. When fetal rat lung explants were harvested at 13.5 d post-conception and cultured for 4 d with increasing doses of total ghrelin, acylated ghrelin, desacyl-ghrelin, ghrelin antagonist [D-Lys(3)-GHRP-6] or obestatin, total and acylated ghrelin significantly increased the total number of peripheral airway buds, whereas desacyl-ghrelin induced no effect, and a GHS-R1a antagonist significantly decreased lung branching. In contrast, obestatin supplementation induced no significant effect in the measured parameters, suggesting that ghrelin has a positive effect in fetal lung development through its GHS-R1a receptor, whereas obestatin has no effect on lung branching[31]. The presence of ghrelin in the lungs is interesting since there is evidence to suggest that ghrelin can attenuate lung injury that occurs in sepsis.

Multiple organ dysfunction is responsible for mortality in sepsis. The lung is frequently the first failing organ in sepsis. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is the primary cause of death under these circumstances. Excessive cytokine-mediated inflammation participates in the pathobiology of lung injury seen in sepsis; while it is evident that immunosuppression is also evident at the onset of sepsis[32-34]. Wu et al[35] showed that plasma levels of ghrelin are significantly reduced in sepsis and that ghrelin administration improves organ blood flow by inhibiting nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB). In an extension of these studies, it was noted that ghrelin administration restored pulmonary levels of ghrelin, reduced lung injury, and increased pulmonary blood flow. These results suggest that severe sepsis-induced lung injury can be ameliorated by inhibition of NF-κB by ghrelin. Thus, ghrelin may serve as a cytoprotective molecule in the lung.

NEUROENDOCRINE AXES IN THE CRITICALLY ILL

Sepsis, excessive inflammation, multiple organ failure and weakness prolong the need for intensive care in critically ill patients. Furthermore, the risk of death is high in the prolonged critically ill patient: about 20% after two weeks and 30% after 3 wk. Prolonged critical illness produces protein hypercatabolism and relative preservation of adipose tissue with fatty infiltration of vital organ systems, thus implying a role for the hypothalamus-pituitary axis in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis. This is so, since, during sepsis and critical illness, the activation of the neuroendocrine stress axis, the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenals, occurs, causing the release of catecholamines and glucocorticoids. Glucocorticoids limit life-threatening acute-phase reactions by means of endogenous inflammation mediators, and produce a shift of the cytokine profiles of the CD4 lymphocytes from Th-1 to Th-2 to temporarily take over the anti-inflammatory functions of the cortisol. Thus, a sustained Th-2 shift is an expression of a persistent hypercortisolism. The suppression of the anti-inflammatory effects of cortisol as a result of states of excessive stress leads to hypercatabolism that is seen in sepsis, toxic shock syndrome and the critically ill[36,37]. This finding led to the study of endocrine organs in the context of critical illness that revealed that the initial “adaptive” neuroendocrine response to critical illness consists primarily of activated anterior pituitary function, while in the chronic phase of critical illness, a uniformly reduced pulsatile secretion of anterior pituitary hormones occurs that could lead to impaired function of target organs. A reduced availability of thyrotropin (TSH)-releasing hormone (TRH), gonadotropin (LH)-releasing hormone (GnRH), the endogenous ligand of the growth hormone (GH)-releasing peptide (GHRP) receptor (ghrelin) and, in very long-stay critically ill men, also of GH-releasing hormone (GHRH) occurs. Pulsatile secretion of GH, TSH and LH can be increased by relevant combinations of releasing factors, which also substantially increase circulating levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, GH-dependent IGF-binding proteins, thyroxine (T4), triiodothyronine (T3) and testosterone. Anabolism is only evoked when GH-secretagogues, TRH and GnRH are administered together, whereas the effect of single hormone treatment is minor. The most important observation is that, in these critically ill subjects, the presence of a high serum concentration of IGF-binding protein 1 predicted death in the ICU. This observation challenged the general belief that adaptive hyperglycemia during critical illness is beneficial. This led to the development of intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill that showed that ICU mortality can be reduced by 42% with strict normalization of glycemia using exogenous insulin infusion[37-42]. This positive result of intensive insulin therapy on the critically ill could be attributed to the prevention of sepsis, multiple organ failure and need for prolonged invasive organ support and intensive care. These results suggest that reduced stimulation of pituitary function seen in prolonged critically ill patients needs to be corrected to reverse the paradoxical ‘wasting syndrome’, and that maintenance of strict normoglycemia with insulin is important to increase the chances of survival of these patients. It is now believed that, from an endocrinological point of view, the acute phase and the later phase of critical illness manifest themselves differently. When the disease process becomes prolonged, there is a uniformly-reduced pulsatile secretion of anterior pituitary hormones, with proportionally reduced concentrations of peripheral anabolic hormones. During critical illness, prolonged activation of the HPA axis can result in hypercortisolemia and hypocortisolemia; both can be detrimental to recovery from critical illness. Recognition of adrenal dysfunction in critically ill patients is difficult because a reliable history is not available, and laboratory results are difficult to interpret[43,44]. For instance, the acute phase of critical illness is characterized by an actively secreting pituitary, but the concentrations of most peripheral effector hormones are low, partly due to the development of target-organ resistance. In contrast, in prolonged critical illness, predominantly hypothalamic suppression of the (neuro)endocrine axes occurs, leading to the low serum levels of the respective target-organ hormones. The adaptations in the acute phase are considered to be beneficial for short-term survival. In the chronic phase, however, the observed (neuro)endocrine alterations contribute to the general wasting syndrome. With the exception of intensive insulin therapy, and perhaps hydrocortisone administration for a subgroup of patients, no hormonal intervention has proven to affect outcome beneficially[45]. In this context, the recently described beneficial actions of ghrelin in the critically ill may have important clinical implications.

GHRELIN IN SEPSIS

Experimental studies

In the rat model of septic shock which was made by caecal ligation and perforation, infusion of ghrelin 10 nmol/kg at the time of operation through the femoral vein, followed by a sc (subcutaneous) injection at 8 h after operation, revealed that, compared to that of the septic shock group, mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) of rats in the ghrelin-treated group increased by 33 % (P < 0.01); the values of +LVdp/dtmax and -LVdp/dtmax increased by 27 % and 33 %, respectively (P < 0.01), but LVEDP decreased by 33 % (P < 0.01). The plasma glucose concentration and myocardial ATP content increased by 53% and 22 %, respectively, whereas plasma lactate concentration decreased by 40% in the ghrelin-treated rats (P < 0.01). The plasma ghrelin level in rats with septic shock was 51% higher than that of rats in the sham group, and was negatively correlated with MABP and blood glucose concentration (r = -0.721 and -0.811, respectively, P < 0.01). The mortality rates were 47% (9/19) in rats with septic shock and 25% (3/12) in rats of the ghrelin-treated group, respectively, suggesting that treatment with ghrelin could at least partially correct the abnormalities of hemodynamics and metabolic disturbance in septic shock of rats[46].

In an extension of these studies, it was noted that even endotoxin-induced shock and mortality could be significantly decreased by ghrelin treatment in rats[47]. Early and late (12 h after lipopolysaccharide injection) treatment with ghrelin markedly increased the plasma glucose concentration, and decreased the plasma lactate concentration. This action on the part of ghrelin in increasing plasma glucose levels (resulting in hyperglycemia) may suggest that it could be harmful in the setting of sepsis or critical illness, since hyperglycemia is believed to accentuate inflammation. In the initial stages of sepsis, hyperglycemia (reactive hyperglycemia) as a result of the enhanced production of hypercortisolemia occurs, whereas in the later stages, hypoglycemia sets in, partly due to hypocortisolemia[48,49]. It was reported that during the early phase of sepsis, plasma glucose levels increased, whereas plasma insulin and glucagon levels remained unchanged, but corticosterone levels increased 2.5-fold over control values. At later stages of sepsis, plasma glucose levels returned to normal, whereas insulin, glucagon, and corticosterone levels increased significantly i.e. 40-fold, 6.5-fold, and 6-fold respectively[48,49]. Therefore, the initial rise and subsequent decline in blood glucose correlated well with a corticosterone followed by an insulin-dependent phenomenon. Thus, blood glucose levels in sepsis depend to a large extent on the balance between corticosterone and insulin levels, and the stage of sepsis[49]. Hence, the ability of ghrelin to enhance plasma glucose levels could, especially in the later stages of sepsis, prevent hypoglycemia that is detrimental and ghrelin may therefore be useful in later stages of sepsis. Furthermore, ghrelin and insulin seem to have both positive and negative feed-back control over each other[50-52], suggesting that ghrelin may be involved in maintaining glucose homeostasis, under both normal conditions and sepsis.

Early treatment with ghrelin significantly attenuated the deficiency in myocardial ATP content, but late treatment with ghrelin had no effect on myocardial ATP content. The plasma ghrelin level was significantly increased in the rats with endotoxin shock, and it increased further after ghrelin administration. Exposure of rat gastric mucosa in vitro to lipopolysaccharide (1.0 to 100 μg/mL) triggered the release of ghrelin from mucosa tissue in a dose- and time-dependent manner[47]. These results suggest that lipopolysaccharide directly stimulates gastric mucosa to synthesize and secrete ghrelin, that may result in a decrease in endotoxin-induced target organ damage.

Ghrelin suppresses production of pro-inflammatory cytokines

Ghrelin-inhibited proinflammatory cytokine production, mononuclear cell binding, and nuclear factor-kappaB activation in human endothelial cells in vitro, and endotoxin-induced cytokine production in vivo, by interacting with growth hormone secretagogue receptors and thus, ghrelin behaves as an endogenous anti-inflammatory molecule[53]. These anti-inflammatory actions of ghrelin may explain why it is able to improve cachexia in heart failure and cancer, and to ameliorate the hemodynamic and metabolic disturbances in septic shock (Figure 1). By virtue of its anti-inflammatory action, ghrelin could play a modulatory role in atherosclerosis as well, especially in obese patients, in whom ghrelin levels are reduced. In a rat model of polymicrobial sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture, though ghrelin levels decreased at early (at 5 h after ligation and puncture) or late sepsis (20 h after ligation and cecal puncture) its receptor was markedly elevated in early sepsis. Moreover, ghrelin-induced relaxation in resistance blood vessels of the isolated small intestine increased significantly during early sepsis, but was not altered in late sepsis. GHSR-1a expression in smooth muscle cells was significantly increased at mRNA and protein levels with stimulation by LPS at 10 ng/mL, suggesting that GHSR-1a expression is upregulated, and vascular sensitivity to ghrelin stimulation is increased in the hyperdynamic phase of sepsis[54] as a compensatory phenomenon to septic process. Furthermore, ghrelin improved tissue perfusion in severe sepsis by downregulating endothelin-1 involving a NF-kappaB-dependent pathway[55].

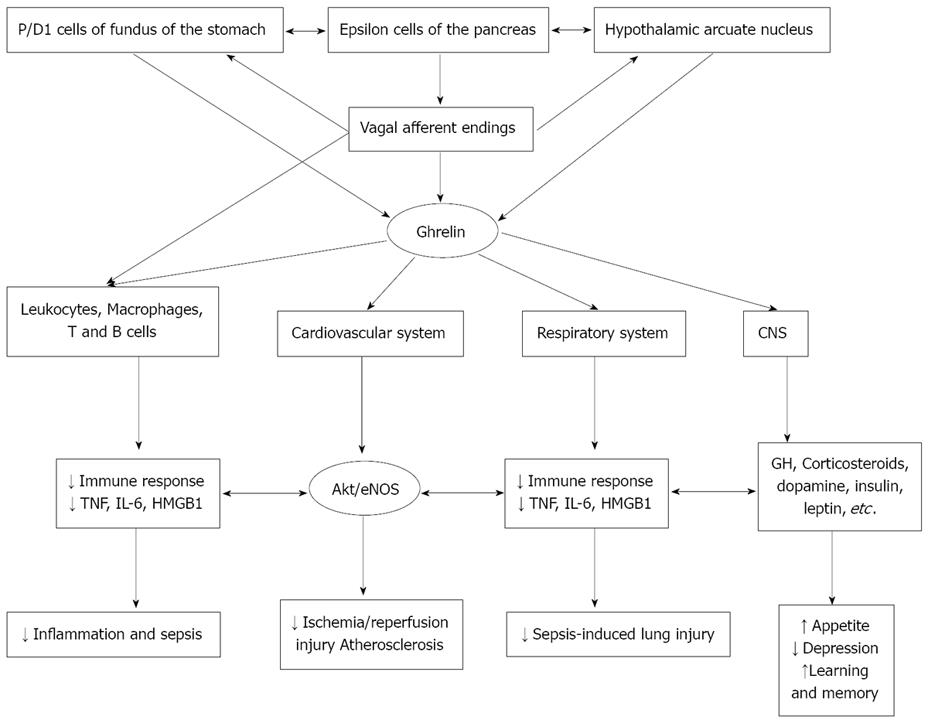

Figure 1 Scheme showing various actions of ghrelin and their possible clinical importance.

Ghrelin seems to be of benefit in suppressing inflammation and sepsis; protects against ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial damage; protects lungs from sepsis-induced damage, enhances appetite, relieves depression and enhances learning and memory. GH: growth hormone; CNS: central nervous system.

These experimental results are supported by the report that during postoperative intra-abdominal sepsis seen in patients, both ghrelin and leptin plasma levels were elevated and positively correlated with both inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) and CRP. However, this hormonal reaction does not seem to be specific to sepsis since a significant increase in both ghrelin and leptin was observed to occur during an uncomplicated postoperative response, although to a lesser extent than was shown in sepsis[56].

Ghrelin stimulates vagus nerve

Ghrelin stimulates the vagus nerve. Since plasma levels of ghrelin were significantly reduced in sepsis; and ghrelin administration improved organ perfusion and function, it was hypothesized that ghrelin decreases pro-inflammatory cytokines in sepsis by means of activation of the vagus nerve. This is so since the vagus mediator, acetylcholine, has potent anti-inflammatory actions and suppresses TNF-α, IL-6 and HMGB1 production by stimulating the alpha7 subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (alpha7nAChR)[57,58]. As predicted, experimental studies revealed that vagotomy prevented ghrelin’s down-regulatory effect on TNF-α and IL-6 production, thus confirming that ghrelin down-regulates proinflammatory cytokines in sepsis through activation of the vagus nerve[59]. It was reported that ghrelin has sympatho-inhibitory properties that are mediated by central ghrelin receptors, involving a NPY/Y1 receptor-dependent pathway[60]. Ghrelin also inhibited the production of HMGB1 by activated macrophages, and also showed anti-bacterial activity[61] that may explain its beneficial action in sepsis and other inflammatory conditions[62-64]. It is important to note that ghrelin ameliorated gut barrier dysfunction[65], an abnormality that is seen in patients with sepsis.

CONCLUSION

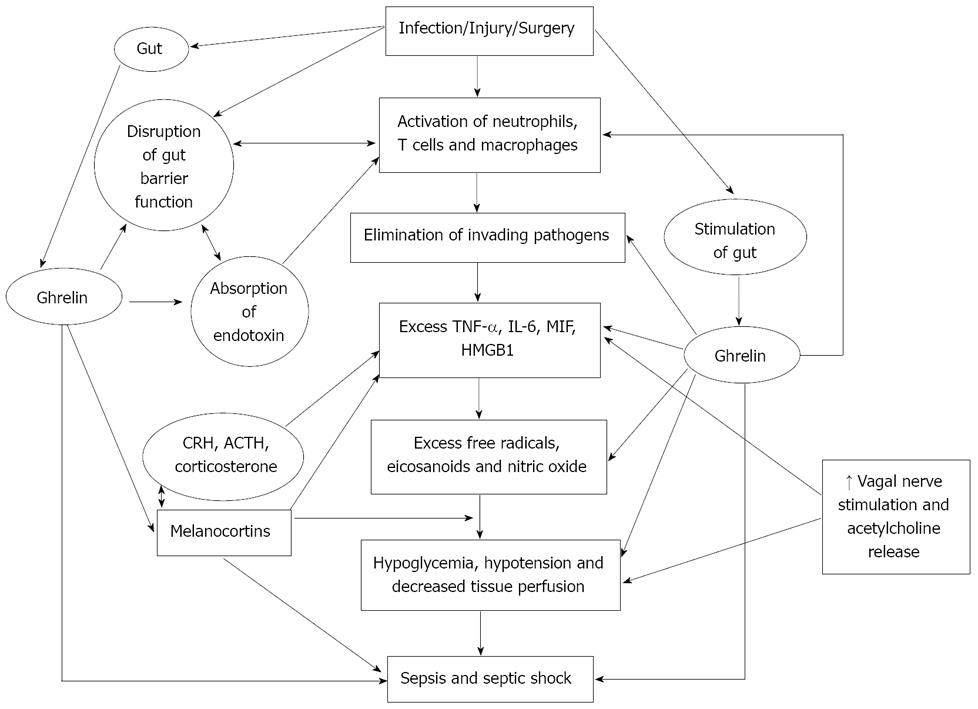

It is evident from the preceding discussion that ghrelin has anti-inflammatory, para-sympathetic stimulatory and sympatho-inhibitory effects that may underlie its beneficial actions in sepsis and other inflammatory conditions. In addition, ghrelin seems to be of significant benefit in improving cachexia in heart failure and cancer, and the ameliorization of the hemodynamic and metabolic disturbances in septic shock (Figure 1). The ability of ghrelin to suppress the synthesis and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6 and HMGB1 suggests that it may find its use in the management of other inflammatory conditions such as atherosclerosis, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, but this remains to be determined. The fact that ghrelin is capable of restoring gut barrier function and possess antimicrobial action suggests that it may be useful in the management of cirrhosis of the liver where gut barrier function is compromised, leading to endotoxin absorption into the circulation. Since failure of gut barrier function is also one of the initial abnormalities seen in sepsis, ghrelin is eminently suited to be employed in its therapy, either by itself, or in combination with other therapies. These actions of ghrelin suggest that ghrelin has the potential to be of significant benefit in sepsis and other critically ill patients (Figure 2). Obviously, large scale human studies are need before ghrelin comes into the clinic in the management of sepsis.

Figure 2 Scheme showing the actions of ghrelin that are relevant to its potential benefit in sepsis.

CRH: corticotropin-releasing hormone; ACTH: adrenocorticotropic hormone.

Ghrelin has been shown to have the ability to alter nerve cell connections and synaptic plasticity[66,67] in the melanocortin system, implying that ghrelin regulates metabolic control by a central action. Melanocortins are known to have anti-inflammatory actions[68,69] suggesting that modulation of the melanocortin system could be yet another means by which ghrelin could bring about its anti-inflammatory action. It has, in fact, been reported that ghrelin inhibited POMC neurons[70], and stimulated the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and corticosterone, suggesting a hypothalamic site of action[71]. Thus, ghrelin could be producing its anti-inflammatory actions by inducing the release of CRH, ACTH and corticosterone.

Ghrelin might also help prevent the stress-induced depression and anxiety[72,73] that is common in patients with sepsis and the critically ill. Ghrelin may thus be of significant benefit in the management of sepsis and the critically ill, provided that clinical trials confirm the anticipated benefits.

Peer reviewers: Vladimir N Uversky, Senior Research Professor, Center for Computational Biology & Bioinformatics, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202, United States; Joseph Fomusi Ndisang, PharmD, PhD, Assistant Professor, College of Medicine, Epartment of Physiology, University of Saskatchewan, 107 Wiggins Road, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Herholdt A E- Editor Liu N