Published online Mar 15, 2010. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i3.146

Revised: November 27, 2009

Accepted: December 4, 2009

Published online: March 15, 2010

Malignant biliary obstruction is commonly due to pancreatic carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma and metastatic disease which are often inoperable at presentation and carry a poor prognosis. Percutaneous biliary drainage and stenting provides a safe and effective method of palliation in such patients, thereby improving their quality of life. It may also be an adjunct to surgical management by improving hepatic and, indirectly, renal function before resection of the tumor.

- Citation: George C, Byass OR, Cast JEI. Interventional radiology in the management of malignant biliary obstruction. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2010; 2(3): 146-150

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v2/i3/146.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v2.i3.146

Malignant biliary obstruction is commonly due to pancreatic carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma and hepatic or nodal metastatic disease. Other causes include gall bladder carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, lymphoma and advanced gastric or duodenal cancer. In these patients with obstructive jaundice, treatment by percutaneous biliary drainage and/or stenting plays an important role in their overall management. Drainage or stenting in patients with malignant biliary obstruction can relieve the symptoms and signs of obstructive jaundice. This optimizes the patient’s condition for surgical resection or for receiving palliative chemotherapy or radiotherapy, bringing about an improvement in their quality of life, even if only for a matter of weeks or months. This article reviews our local practice in the care of these patients with an overview of percutaneous biliary drainage and stenting (PBDS) in malignant biliary obstruction.

Our hospital is a tertiary referral centre where patients with obstructive jaundice are under the care of an upper gastrointestinal (GI) surgeon who investigates them for suitability for surgical resection with the aim of a curative outcome. The clinical, imaging and pathological investigative results are assimilated and presented at an upper GI cancer multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meeting. Percutaneous biliary intervention is provided as an adjunct to planned surgical resection or as a palliative procedure for inoperable malignant biliary obstruction with over 100 cases performed every year.

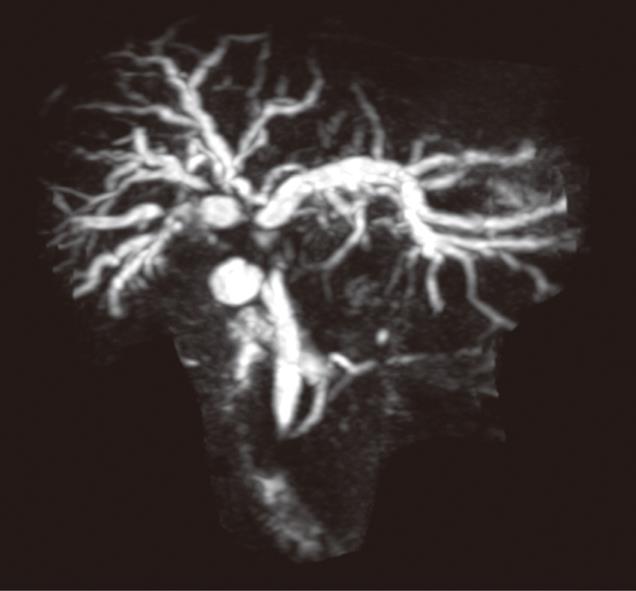

Patient preparation is essential for a safe, effective, and successful biliary intervention. Pre-procedure preparation of patients includes a single dose of prophylactic antibiotics (cefuroxime and metronidazole), checking the coagulation results and obtaining informed consent. The main contraindication to PBDS is deranged clotting parameters which can usually be corrected with intramuscular or intravenous Vitamin K or fresh frozen plasma transfusion. Ascites is a relative contra-indication and, if present, an ascitic drain is routinely placed before or at the time of PBDS. The pre-procedure imaging is reviewed and is an important aspect of interventional radiology practice. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography may be useful in more complex cases to plan drainage and stenting in malignancies causing hilar, segmental or proximal common bile duct (CBD) obstructions (Figure 1). A preliminary ultrasound (US) of the liver helps in the assessment of intra and extra hepatic biliary duct dilatation and in locating the gall bladder and hepatic mass lesions. The US scan also helps plan the approach and allows selective ductal puncture. The procedure is usually performed under local anaesthetic (1% Lidocaine) with sedo-analgesia using intravenous midazolam (1-6 mg) and fentanyl (25-100 micrograms) under continuous monitoring until the end of the procedure.

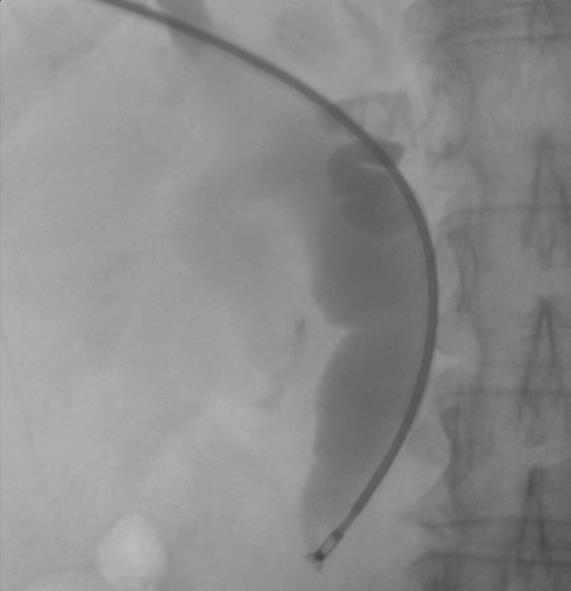

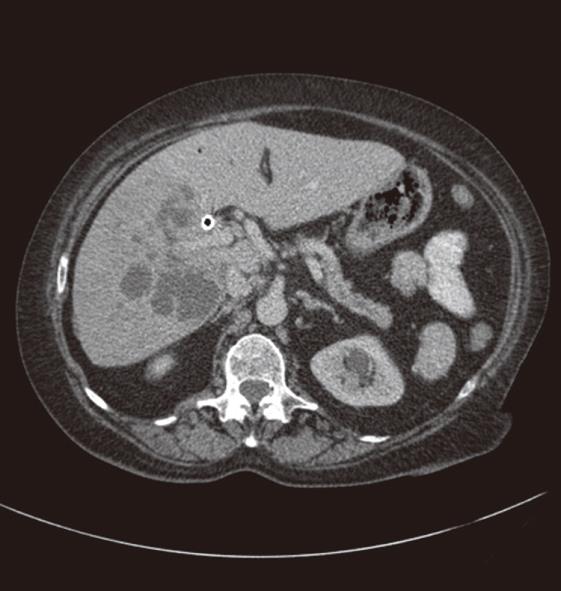

Patients presenting with obstructive jaundice due to malignancy with cholangitis or very high bilirubin levels undergo external biliary drainage after diagnostic imaging, usually with contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT). This relieves jaundice and sepsis and decreases the risk of hepato-renal failure. The tumor or ampulla is not crossed at the request of local surgeons to avoid the risk of causing peri-tumoral inflammation and /or pancreatitis, which may make subsequent surgical resection more difficult. This provides a stopgap prior to additional imaging with endoscopic ultrasound and MDT decision on definitive management. Prolonged external drainage is not usually required but in this event, instilling the drained bile down a naso-jejunal tube can minimize fluid and bile salt loss. An 8F Flexima pigtail drainage catheter (Boston Scientific, Natick, USA) is usually placed with a locking loop to prevent drain migration out of the duct (Figure 2).

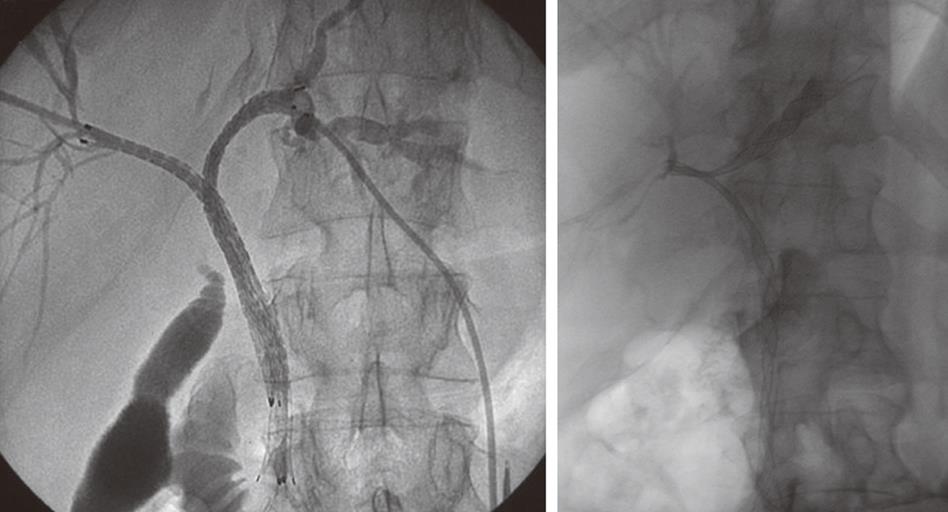

In patients deemed unfit for surgery due to co-morbidity or an unresectable tumor, percutaneous biliary stenting is performed. At the time of this procedure, it is possible to obtain tissue for diagnostic confirmation by endobiliary biopsy (Figure 3). Diagnostic confirmation is particularly important in patients who will proceed to chemotherapy or radiotherapy. An 8F Arrow-Flex sheath (Arrow International, Reading, USA) is placed percutaneously into the biliary tree as this accepts standard bronchoscopic or endoscopic biopsy forceps.

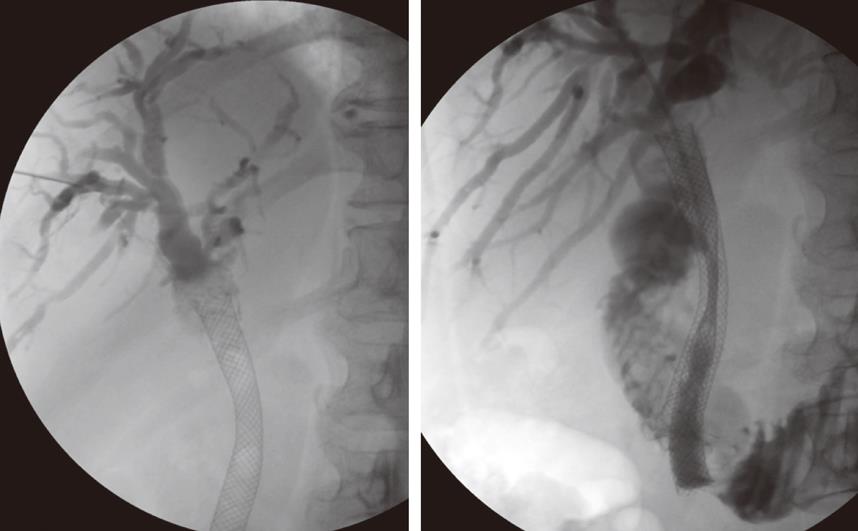

Following biopsy the obstructing lesion is crossed using a combination of a biliary manipulation catheter and hydrophilic guide wire (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). These are then exchanged for a stiff guide wire and the stent delivery system respectively. Ten millimeter diameter Wallstent (Boston Scientific, Galway, Ireland) or Nitinella (Ella CS, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic) uncovered metal stents are used and in most cases the distal end of the stent is placed across the ampulla. This ensures maximum biliary drainage and reduces the risk of post-procedure cholangitis. Multiple stent placements may be required depending on the location of the stricture or strictures (Figure 4A and B). Hilar strictures often require stent placement via the right and left hepatic ductal systems. Occasionally, a Flexima biliary catheter system (Boston Scientific, Natick, USA) is placed. This internal-external drainage catheter (IEDC) acts as a bridge between early intervention and definitive surgical management by maintaining homeostasis, as the bile flow into the bowel resumes. Another indication for an IEDC is in cases of cholangiocarcinoma where intraluminal brachytherapy is being considered (Figure 5). A 192-iridium wire with appropriate measurements is placed into the lumen of the drainage catheter for 2 d and the lesion is subsequently stented. This results in improvement in local disease control and increases long-term stent patency. Antibiotics are prescribed for 48 h for those patients who undergo biliary stenting and all have a post-procedure care plan inserted into the case notes. The index team on the wards usually looks after post-procedure pain relief.

Stents can occasionally block due to either biliary sludge or tumor recurrence resulting in the reappearance of jaundice. Recurrent tumor growth can be either through the stent struts or overgrowth of the proximal or distal ends (Figure 6A). US and CT will aid in diagnosing and planning further intervention in these patients. Endoscopic intervention can serve as a complementary procedure where a plastic stent is inserted into the blocked primary stent. However, if this is not possible, then PBDS will be needed where a similar size or smaller metal stent is coaxially inserted into the blocked one with or without balloon dilatation (Figure 6B).

Proximal tumor progression and stent overgrowth may result in segmental ductal obstruction, which can prove technically difficult or impossible to satisfactorily resolve.

Stenting and drainage of the biliary tract is a safe procedure but does have its share of complications which can be divided into immediate and late complications. Immediate complications include pain at the site of puncture; bile leak; intrahepatic and extrahepatic bleeding, including haemobilia; pneumothorax; haemothorax; septicaemia; and catheter related problems of kinking or dislocation. Patients may find the left lobe punctures less painful as these do not cross the intercostal space, although bile leak or bleeding may be more common as there may be less liver to tamponade the puncture tract. Bile leak and bleeding may be mild to severe, resulting in pain secondary to peritonitis, especially referred pain at the shoulder tip. Pneumothorax and haemothorax are rare and may result from traversing the pleura. Late complications include cholangitis, pancreatitis, liver abscess (Figure 7), septicaemia, drainage catheter or stent blockage, and arterial or venous biliary fistula. Stent occlusion may result from tumor in-growth or may be due to biliary sludge or calculi.

In our experience, most complications can be treated conservatively although the more serious ones may need further radiological or surgical intervention. Procedure related mortality is low although 30-day mortality is significant, usually due to the underlying disease process. In our review[1] of 90 stent deployments in 76 patients (male: female = 40: 36; age range = 43 to 94 years) with malignant biliary strictures, there were certain predictors of likely poor outcome following biliary stenting. The causes of malignant biliary obstruction were: pancreatic carcinoma (55.3%); cholangiocarcinoma (11.8%); ampullary carcinoma (6.6%); metastatic carcinoma (18.4%); and other causes (7.9%). The strictures were located at the hilum in 13.1%, mid CBD in 26.3%, distal CBD in 59.2%, and anastomosis in 1.3%. In most cases the stents were placed across the ampulla. Technical success was obtained in all cases. Mean primary stent patency rate was 471 d with a mean patient survival of 160 d (5-656 d). Thirty days mortality was 14/76 (18%) with a complication rate of 9/76 (11.8%). Our results are comparable with those in the literature[2,3]. Patients were divided into 2 groups: those who died within 30 d of stenting and those who survived beyond this. The mean bilirubin, mean albumin, mean creatinine, and presence of metastatic disease were analyzed in these 2 groups. The results (Table 1) show that independent poor predictors of early mortality were dictated by high serum bilirubin, high serum creatinine, and low serum albumin. However, in our experience, the presence of metastatic disease was not a statistically significant predictor of early mortality.

| Early < 30 d | Survival > 30 d | ||

| P value | |||

| mortality | |||

| (n = 14) | (n = 62) | ||

| Mean bilirubin (umol/L) | 247 | 236 | < 0.01 |

| Mean albumin (g/L) | 21.3 | 25.2 | < 0.01 |

| Mean creatinine (umol/L) | 122 | 93 | < 0.01 |

| Metastatic disease | 8 (57%) | 29 (47%) | Not significant |

PBDS is a recognized and established method of palliation in patients with malignant biliary obstruction. In most patients, the malignant biliary obstruction is due to pancreatic adenocarcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma. Treatment options for achieving biliary drainage include percutaneous, endoscopic, and surgical biliary interventions, with each method having its own advantages and disadvantages. In many hospitals, endoscopic placement of a biliary stent is the preferred method but this depends on local practice and availability of endoscopic interventional expertise. Type of biliary stricture, MDT discussion outcome, and patient choice will all contribute towards the final treatment plan. Whatever method of intervention is chosen, the main aim is to provide palliation by relieving the pain and symptoms related to jaundice, including preventing and/or treating deranged liver function and cholangitis secondary to biliary obstruction.

Percutaneous biliary drainage procedures have been practiced for more than 40 years[4,5] with modifications and improvements[6-8] in techniques. Technological advances in stent design have made their deployment safe and effective, making PBDS a recognized and acceptable treatment option in patients with malignant biliary obstruction. Metal stents are used in our hospital in almost all cases, except for biliary obstruction due to lymphoma, in which plastic stents are used. The endoscopic interventional team usually inserts plastic stents and the technically unsuccessful ones are referred to interventional radiology for percutaneous stent insertion.

Metal stents have higher patency rates, shorter hospital stay for patients, and lower overall cost than plastic stents[8]. Covered metal stents[9-11] are now available but stent migration, occlusion of side-branches, including cystic or pancreatic ducts causing cholecystitis and pancreatitis respectively, are potential complications that may limit their use. The use of self-expanding metal stents has increased, due to fewer long-term complications than are seen with the small diameter plastic stents, particularly early stent occlusion[12]. It is well known that advances in adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy also form part of the palliative treatment, which prolongs life expectancy in patients who have had stents inserted and thereby possibly outliving the stent patency period. Evidence indicates that those patients with cholangiocarcinoma who are unsuitable for surgery should be offered brachytherapy or photodynamic therapy in addition to biliary stenting, as median survival and stent patency is prolonged compared to stenting alone[13]. Newer methods describing “crisscross” stent deployment for trisectoral drainage of biliary hilar malignancy have been reported[14].

The majority of strictures of the mid and lower common bile ducts can be drained effectively by the endoscopic approach. High obstructions, bilateral or multiple strictures and previous upper GI surgery may make endoscopic stent placement difficult or impossible[3] and percutaneous stent placement will usually be successful. Even if both the right and the left hepatic ducts are obstructed due to a hilar lesion, draining one side alone will usually relieve jaundice and pruritus. However, if the jaundice is not relieved with only one side being drained the other side can also be drained. If the initial cholangiogram shows communication between the right and left sides of the liver in a patient with a hilar lesion, both lobes should be drained, as there is a significant likelihood of infection of the contralateral lobe if unilateral drainage is performed[15,16]. The advocates[17-19] of unilateral drainage quote lower complication rates, but warn that contrast media overfilling of the undrained ducts should be avoided to decrease risk of infection. Most interventional radiologists puncture the ducts in the right lobe which drains a larger volume of liver, assuming that the right lobe still functions as the dominant of the two. As this paper highlights and others[20] have stressed, imaging review is important for planning drainage and stenting of hilar obstruction.

Technical success of PBDS has been reported as more than 90% and clinical success as more than 75% in all major series in a review study[21]. Endoscopic drainage and stenting is the primary tool for drainage of distal obstruction with PBDS, mostly reserved for cases where endoscopic intervention is not possible. For treatment of patients with proximal obstruction, both endoscopic and percutaneous methods are used as the primary tool but the choice of technique in such patients depends on the specific patient circumstances, local availability and expertise.

Review of percutaneous biliary stenting with metallic wall stents reports an overall complication rate of 8%-42%, with early complications ranging from 9.7% to 17%[3]. 17% of patients died within 2 wk of percutaneous stent insertion. It is unlikely that this procedure served any benefit to these patients. An improvement in quality of life may be obtained by eliminating biliary obstruction for patients surviving 1 mo or more but the difficulty is identifying those patients who would be best served by supportive care alone. A more recent review[21] showed that in most series, procedure-related mortality ranged from 0% to 3%, 30-day mortality ranged from 2% to 20% and was usually related to the underlying disease. This was because these patients usually have advanced disease with deranged liver function, malnutrition, and cancer cachexia. This study also found that complications ranged from 8% to 30% and could, in the majority of cases, be treated conservatively. About 10%-30% of patients will have recurrent jaundice at some point in their disease after PBDS which may require re-intervention[21].

PBDS offers a safe and effective method in providing palliative treatment for patients with malignant biliary obstruction. Discussion and consensus at multidisciplinary meetings will dictate the best treatment option for such patients. Percutaneous biliary intervention has an important role in the management of patients with malignant biliary obstruction with a view to improving their quality of life, irrespective of their suitability for surgical intervention.

Peer reviewer: Marco Braga, Professor of Surgery, San Raffaele University, Via Olgettina 60, 20132 Milan, Italy

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Yang C

| 1. | Wong FH, Roy-Choudhury SH, Breen DJ, Nicholson AA, Cast JEI. Factors Influencing Outcome in Percutaneous Metallic Stenting for Malignant Biliary Obstruction. RSNA. 2003;Scientific Exhibit. |

| 2. | Dinkel HP, Triller J. [Primary and long-term success of percutaneous biliary metallic endoprotheses (Wallstents) in malignant obstructive jaundice]. Rofo. 2001;173:1072-1078. |

| 3. | Indar AA, Lobo DN, Gilliam AD, Gregson R, Davidson I, Whittaker S, Doran J, Rowlands BJ, Beckingham IJ. Percutaneous biliary metal wall stenting in malignant obstructive jaundice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:915-919. |

| 4. | Arner O, Hagberg S, Seldinger SI. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography: puncture of dilated and non dilated bile ducts under roentgen television control. Surgery. 1962;52:561-571. |

| 5. | Kaude JV, Weidenmier CH, Agee OF. Decompression of bile ducts with the percutaneous transhepatic technic. Radiology. 1969;93:69-71. |

| 6. | Molnar W, Stockum AE. Relief of obstructive jaundice through percutaneous transhepatic catheter--a new therapeutic method. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1974;122:356-367. |

| 7. | Laméris JS, Obertop H, Jeekel J. Biliary drainage by ultrasound-guided puncture of the left hepatic duct. Clin Radiol. 1985;36:269-274. |

| 8. | Lammer J, Hausegger KA, Flückiger F, Winkelbauer FW, Wildling R, Klein GE, Thurnher SA, Havelec L. Common bile duct obstruction due to malignancy: treatment with plastic versus metal stents. Radiology. 1996;201:167-172. |

| 9. | Hausegger KA, Thurnher S, Bodendörfer G, Zollikofer CL, Uggowitzer M, Kugler C, Lammer J. Treatment of malignant biliary obstruction with polyurethane-covered Wallstents. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:403-408. |

| 10. | Schoder M, Rossi P, Uflacker R, Bezzi M, Stadler A, Funovics MA, Cejna M, Lammer J. Malignant biliary obstruction: treatment with ePTFE-FEP- covered endoprostheses initial technical and clinical experiences in a multicenter trial. Radiology. 2002;225:35-42. |

| 11. | Miyayama S, Matsui O, Akakura Y, Yamamoto T, Nishida H, Yoneda K, Kawai K, Toya D, Tanaka N, Mitsui T. Efficacy of covered metallic stents in the treatment of unresectable malignant biliary obstruction. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:349-354. |

| 12. | Schmassmann A, von Gunten E, Knuchel J, Scheurer U, Fehr HF, Halter F. Wallstents versus plastic stents in malignant biliary obstruction: effects of stent patency of the first and second stent on patient compliance and survival. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:654-69. |

| 13. | Killeen RP, Harte S, Maguire D, Malone DE. Achievable outcomes in the management of proximal cholangiocarcinoma: an update prepared using "evidence-based practice" techniques. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:54-57. |

| 14. | Bae JI, Park AW, Choi SJ, Kim HP, Lee SJ, Park YM, Yoon JH. Crisscross-configured dual stent placement for trisectoral drainage in patients with advanced biliary hilar malignancies. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:1614-1619. |

| 15. | Lee MJ, Dawson SL, Mueller PR, Saini S, Hahn PF, Goldberg MA, Lu DS, Mayo-Smith WW. Percutaneous management of hilar biliary malignancies with metallic endoprostheses: results, technical problems, and causes of failure. Radiographics. 1993;13:1249-1263. |

| 16. | Inal M, Akgül E, Aksungur E, Seydaoğlu G. Percutaneous placement of biliary metallic stents in patients with malignant hilar obstruction: unilobar versus bilobar drainage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:1409-1416. |

| 17. | Chang WH, Kortan P, Haber GB. Outcome in patients with bifurcation tumors who undergo unilateral versus bilateral hepatic duct drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:354-362. |

| 18. | Cowling MG, Adam AN. Internal stenting in malignant biliary obstruction. World J Surg. 2001;25:355-359; discussion 359-361. |

| 19. | Rerknimitr R, Kladcharoen N, Mahachai V, Kullavanijaya P. Result of endoscopic biliary drainage in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:518-523. |

| 20. | Freeman ML, Overby C. Selective MRCP and CT-targeted drainage of malignant hilar biliary obstruction with self-expanding metallic stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:41-49. |

| 21. | van Delden OM, Laméris JS. Percutaneous drainage and stenting for palliation of malignant bile duct obstruction. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:448-456. |