Published online Dec 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i12.600

Revised: October 31, 2014

Accepted: November 7, 2014

Published online: December 16, 2014

Processing time: 173 Days and 5.4 Hours

AIM: To assess the risk of failing to detect diminutive and small colorectal cancers with the “resect and discard” policy.

METHODS: Patients who received colonoscopy and polypectomy were recruited in the retrospective study. Probable histology of the polyps was predicted by six colonoscopists by the use of NICE classification. The incidence of diminutive and small colorectal cancers and their endoscopic features were assessed.

RESULTS: In total, we found 681 cases of diminutive (1-5 mm) lesions in 402 patients and 197 cases of small (6-9 mm) lesions in 151 patients. Based on pathology of the diminutive and small polyps, 105 and 18 were non-neoplastic polyps, 557 and 154 were low-grade adenomas, 18 and 24 were high-grade adenomas or intramucosal/submucosal (SM) scanty invasive carcinomas, 1 and 1 were SM-d carcinoma, respectively. The endoscopic features of invasive cancer were classified as NICE type 3 endoscopically.

CONCLUSION: The risk of failing to detect diminutive and small colorectal invasive cancer with the “resect and discard” strategy might be avoided through the use of narrow-band imaging observation with the NICE classification scheme and magnifying endoscopy.

Core tip: Discarding a polyp without performing histological evaluation runs the risk of failing to detect small invasive colorectal cancer. Retrospectively, we aimed to assess the risk of failing to detect diminutive and small colorectal invasive cancer with the “resect and discard” strategy by using the NICE classification scheme with a magnifying endoscope. We reviewed and assessed 878 polyps less than 1 cm in diameter detected in our hospital. Among them, 2 SM-d carcinomas were found and both of their optical features were classified as NICE type 3. We concluded that the risk of failing to detect diminutive and small invasive colorectal cancer with the “resect and discard” strategy might be prevented by employing NICE classification under narrow-band imaging magnification.

- Citation: Hattori S, Iwatate M, Sano W, Hasuike N, Kosaka H, Ikumoto T, Kotaka M, Ichiyanagi A, Ebisutani C, Hisano Y, Fujimori T, Sano Y. Narrow-band imaging observation of colorectal lesions using NICE classification to avoid discarding significant lesions. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(12): 600-605

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i12/600.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i12.600

Removal of all adenomatous polyps during colonoscopy has been standardized worldwide. As the National Polyp Study (NPS) demonstrated that removal of all adenomatous polyps could significantly reduce colorectal cancer incidence and mortality[1], it has been standard practice for all polyps to be retrieved and submitted for pathological evaluation. Recently, however, the “resect and discard” policy was advocated[2,3]. According to this strategy, a hyperplastic polyp in recto-sigmoid colon would be left to reduce the risk of polypectomy, and diminutive (1-5 mm) or small (6-9 mm) lesions would be resected and discarded to eliminate the costs associated with histological evaluation. However, discarding polyps without performing histology runs the risk of failing to detect diminutive and small colorectal invasive cancer, which would otherwise be received surgery. Recently, the NICE classification was proposed as a valid tool for not only differentiating hyperplastic from adenomatous polyps, but also predicting SM-d carcinomas in colorectal tumors[4,5].

The aim of this study was to investigate the risk of failing to detect diminutive and small colorectal invasive cancers in real-time using the “resect and discard” strategy with NICE classification and magnifying endoscopy.

Consecutive patients who underwent colonoscopy and received polypectomy in our institution were recruited in the retrospective study.

For bowel preparation, patients ingested 1.5 to 2 L of polyethylene glycol solution in the morning before the procedure. Six colonoscopists performed all colonoscopy procedures up to the cecum with high-resolution endoscope (CF-H260AZI; Olympus, Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and NBI magnification. We used a video endoscope system (EVIS LUCERA SPECTRUM; Olympus, Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and a digital image filing system (SolemioENDO; OLYMPUS, Tokyo, Japan). In NBI mode with this system, the center wavelengths of the dedicated trichromatic optical filters are 540 and 415 nm, with bandwidths of 30 nm. We set the optical enhancement at enhancement mode A8 and color mode 3. Macroscopic type of the lesions were based on the Paris classification of superficial gastrointestinal lesions[6].

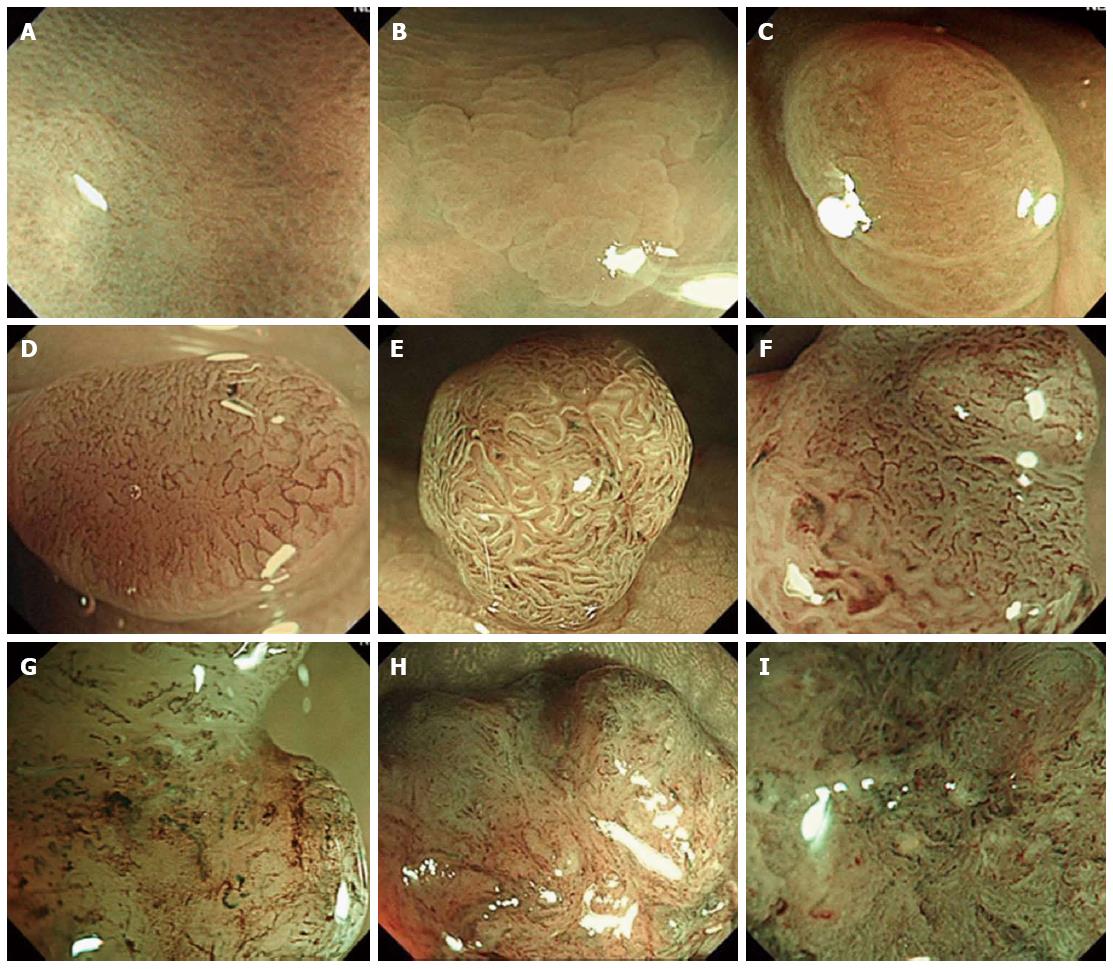

All of the lesions were initially detected by conventional view, and then examined by NBI with magnification to evaluate the endoscopic features on the surface. All lesions were then classified into 3 types based on NICE classification, which consists of 3 types as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1[4,7].

| Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 | |

| Color | Same or lighter than background | Browner relative to background (verify color arises from vessels) | Brown to dark brown relative to background; sometimes patchy whiter areas |

| Vessels | None, or isolated lacy vessels may be present coursing across the lesion | Brown vessels surrounding white structures2 | Has area(s) of disrupted or missing vessels |

| Surface Pattern | Dark or white spots of uniform size, or homogeneous absence of pattern | Oval, tubular or branched white structures surrounded by brown vessels2 | Amorphous or absent surface pattern |

| Most likely pathology | Hyperplastic | Adenoma3 | Deep submucosal invasive cancer |

| Treatment | Follow up | Polypectomy/EMR/ESD | Surgical operation |

We reviewed medical records using SolemioENDO colonoscopy system and detected polyps less than 1 cm in diameter, and we aggregated the lesion size data (1-5/6-9 mm), location (right/left-side), shape (pedunculated/sessile/flat/depressed), NICE classification category, and pathological diagnosis. The incidence of diminutive and small invasive colorectal carcinoma and their endoscopic features were also assessed.

A total of 878 polyps less than 1 cm in diameter were detected in 468 patients. Among the cohort, 290 patients were male, 178 were female, and average age was 66.3 years old (32-97, SD). The average value of polyp size was 4.7 mm (1-9, SD) and 542 of them were detected in the right-side colon, while 336 were detected in the left side. A total of 12 polyps were pedunculated, 274 were sessile, 590 were flat, and 2 were depressed in shape. Based on histology, 123 were non-neoplastic polyps [100 hyperplastic, 13 Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyp (SSA/P), 10 other], 753 were adenomas (717 tubular, 26 tubulovillous, 10 serrated), and 2 were invasive cancers.

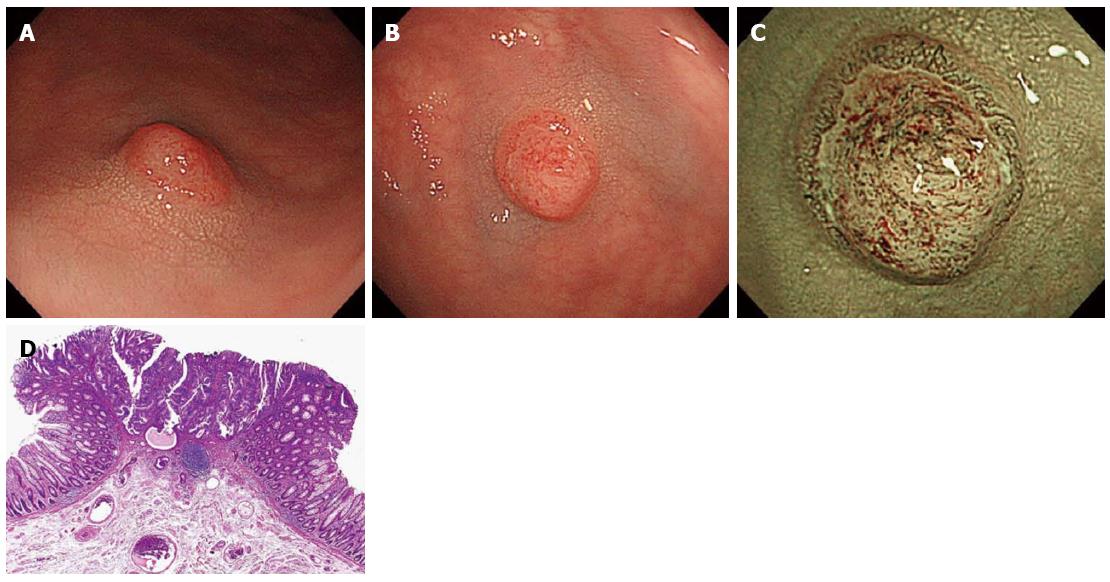

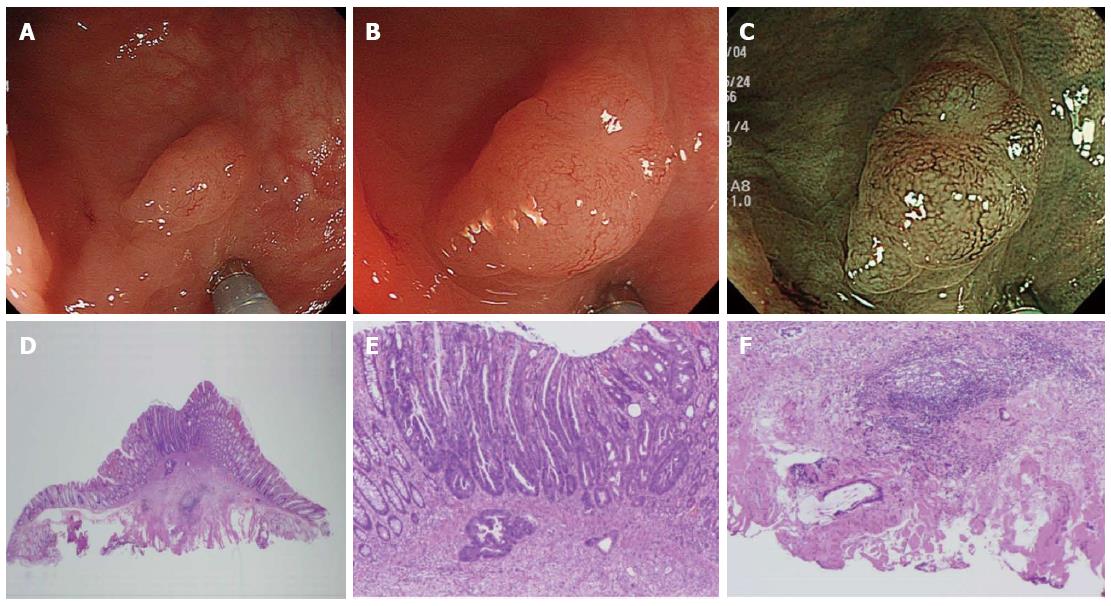

Among the 2 groups divided based on polyp size (diminutive and small), we detected 681 diminutive polyps in 402 patients and 197 small polyps in 151 patients. The 681 diminutive polyps consisted of 105 non-neoplastic polyps, 557 low-grade adenomas, 18 high-grade adenomas or intramucosal/SM scanty invasive carcinomas, and 1 SM-d carcinoma. Additionally, the 197 small polyps consisted of 18 non-neoplastic polyps, 154 low-grade adenomas, 24 high-grade adenomas or intramucosal/SM scanty invasive carcinomas, and 1 SM-d carcinoma. The optical features of invasive cancer could be diagnosed as NICE type 3 endoscopically (Figures 2 and 3).

Morson[8] described the adenoma-carcinoma sequence in detail, which led to recognition among clinicians worldwide of the course of progression from adenomas to colorectal cancers. Removal of all adenomatous polyps during colonoscopy has been standardized worldwide. As the NPS demonstrated that removal of all adenomatous polyps could significantly reduce colorectal cancer incidence and mortality[1]. At present, it is routine practice to retrieve polyps for pathological evaluation because the accuracy of diagnosis to distinguish non-neoplastic from neoplastic colorectal lesions under observation with white light is not high and usually has a limit of 59% to 84%[9-14].

Image-enhanced endoscopy including NBI was introduced in 2006 and its use has since spread widely and rapidly worldwide, which contributed to improved diagnostic precision even without the use of magnification[15]. Furthermore, the introduction of a concept called the “confidence level” has further improved diagnostic precision.

According to this concept, cases are classified as high confidence (HC) or low confidence (LC), based on the degree of diagnostic certainty. It has already been proven that diagnostic precision is enhanced when only HC cases are subjected to endoscopic diagnosis[2,3]. It was reported that the accuracy rate of diagnosis to distinguish non-neoplastic from neoplastic colorectal lesions improved over 90% in 2009 at academic centers in the United Kingdom and United States through the use of NBI (non-magnifying) for HC cases. In other words, the accuracy of endoscopic diagnosis with HC can be comparable to that of pathological diagnosis. Recently, the “resect and discard” policy was advocated[2,3]. According to this strategy, a hyperplastic polyp in recto-sigmoid colon would be left to reduce the risk of polypectomy, and diminutive or small adenomas would be resected and discarded so as to eliminate the cost of pathological examination. However, discarding polyps without performing histology increases the risk of failing to detect diminutive and small colorectal invasive cancers, which would otherwise be received surgery, and if a recto-sigmoid polyp is left in situ, there is a risk of leaving behind a neoplastic lesion if the diagnosis is incorrect.

In the present study, among 878 polyps less than 1 cm in diameter, 2 SM-d carcinomas were identified (Tables 2 and 3). One had a diameter of 4 mm and the other, 6 mm. Both were in the sigmoid colon, with the shape of IIa + IIc, depressed type, and had optical features of invasive carcinoma classified as NICE type 3. Consequently, these 2 patients received adequate surgical treatment (Figures 2 and 3). Additionally, we diagnosed 53 diminutive and 21 small polyps classified as NICE type 1, meaning that they were non-neoplastic and would, according to the “resect and discard” strategy, be left in situ if located in the recto-sigmoid colon (Table 3). Of these polyps, 11 diminutive polyps and 9 small polyps were adenomas. The rate of false diagnosis was not low, presumably because the study was not prospective and cases included not only HC cases but also LC cases. Nonetheless, all of the adenomas diagnosed as NICE type 1 were adenomas with low-grade rather than high-grade atypia. The present data might suggest that the risk of failing to detect diminutive and small invasive colorectal cancers and that of leaving high-grade adenomas or intramucosal/SM scanty invasive carcinomas in situ with the “resect and discard” strategy could be avoided through the use of NBI observation with NICE classification and a magnifying endoscope.

| Total patient | 468 |

| Male/female | 290/178 |

| Mean age | 66.3 (32-97, SD:) |

| Polyps | 878 |

| Mean size (mm) | 4.7 (1-9, SD:) |

| Location (right side/left side) | 542/336 |

| Shape (pedunculated/sessile/ flat/depressed) | 12/274/590/2 |

| Histology | |

| Non-neoplastic | 123 (HP:100, SSA/P:13, other:10) |

| Adenoma | 753 (TA:717, TVA:26, SA:10) |

| Grade (low/high) | 711/42 |

| Invasive cancer | 2 |

| NICE classification | Non-neoplastic | Adenoma (low/high) | Invasive cancer |

| Diminutive/small | Diminutive/small | Diminutive/small | |

| NICE 1 | 42/12 | 11 (11/0)/9 (9/0) | 0/0 |

| NICE 2 | 63/6 | 564 (546/18)/169 (145/24) | 0/0 |

| NICE 3 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 |

The present study had some limitations. This was a single-center retrospective study and confidence levels were not determined. Further prospective research is required to validate the reliability of using the NICE classification with a magnifying endoscope in real-time colonoscopy.

In conclusion, the risk of failing to detect diminutive and small invasive colorectal cancers with the “resect and discard” strategy might be prevented by employing NICE classification under NBI magnification.

The “resect and discard” strategy offers costs savings benefits because it does not involve histological evaluation of tissue specimens; however, when discarding polyps without evaluating them histologically there is a risk of failure to detect invasive colorectal cancer.

Recently, the NICE classification was proposed as a valid tool for not only differentiating hyperplastic from adenomatous polyps, but also predicting SM-d carcinomas in colorectal tumors. In the present study the authors aimed to assess the risk of failing to detect diminutive and small colorectal cancers in real-time using the “resect and discard” policy with NICE classification under narrow-band imaging (NBI) magnification.

Previous studies about the “resect and discard” strategy have reported that in-vivo optical diagnosis with high-definition white light followed by NBI without magnification and chromoendoscopy seemed to be acceptable to assess polyp histopathology and future surveillance intervals. In the present study the authors innovated NICE classification and magnifying endoscopy to predict simply SM-d carcinomas among diminutive or small colorectal polyps.

The present data might suggest that the risk of failing to detect diminutive and small invasive colorectal cancers and that of leaving high-grade adenomas or intramucosal/SM scanty invasive carcinomas in situ with the “resect and discard” strategy might be prevented by employing NICE classification under NBI magnification.

NICE classification is very simple and based on 3 characteristics including: (1) lesion color; (2) microvascular architecture; and (3) surface pattern, which consists of 3 types as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

The paper proposes the “resect and discard” strategy of dimunitive and small polyps according their endoscopic features using NBI colonoscopes in conjunction with the NICE classification system.

P- Reviewer: Karagiannis JA, Parsak C S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O’Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977-1981. |

| 2. | Ignjatovic A, East JE, Suzuki N, Vance M, Guenther T, Saunders BP. Optical diagnosis of small colorectal polyps at routine colonoscopy (Detect InSpect ChAracterise Resect and Discard; DISCARD trial): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1171-1178. |

| 3. | Rex DK. Narrow-band imaging without optical magnification for histologic analysis of colorectal polyps. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1174-1181. |

| 4. | Hewett DG, Kaltenbach T, Sano Y, Tanaka S, Saunders BP, Ponchon T, Soetikno R, Rex DK. Validation of a simple classification system for endoscopic diagnosis of small colorectal polyps using narrow-band imaging. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:599-607.e1. |

| 5. | Hayashi N, Tanaka S, Hewett DG, Kaltenbach TR, Sano Y, Ponchon T, Saunders BP, Rex DK, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic prediction of deep submucosal invasive carcinoma: validation of the narrow-band imaging international colorectal endoscopic (NICE) classification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:625-632. |

| 6. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. |

| 7. | Iwatate M, Ikumoto T, Hattori S, Sano W, Sano Y, Fujimori T. NBI and NBI Combined with Magnifying Colonoscopy. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2012;2012:173269. |

| 8. | Morson B. President’s address. The polyp-cancer sequence in the large bowel. Proc R Soc Med. 1974;67:451-457. |

| 9. | Machida H, Sano Y, Hamamoto Y, Muto M, Kozu T, Tajiri H, Yoshida S. Narrow-band imaging in the diagnosis of colorectal mucosal lesions: a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2004;36:1094-1098. |

| 10. | Apel D, Jakobs R, Schilling D, Weickert U, Teichmann J, Bohrer MH, Riemann JF. Accuracy of high-resolution chromoendoscopy in prediction of histologic findings in diminutive lesions of the rectosigmoid. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:824-828. |

| 11. | Tischendorf JJ, Wasmuth HE, Koch A, Hecker H, Trautwein C, Winograd R. Value of magnifying chromoendoscopy and narrow band imaging (NBI) in classifying colorectal polyps: a prospective controlled study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1092-1096. |

| 12. | De Palma GD, Rega M, Masone S, Persico M, Siciliano S, Addeo P, Persico G. Conventional colonoscopy and magnified chromoendoscopy for the endoscopic histological prediction of diminutive colorectal polyps: a single operator study. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2402-2405. |

| 13. | Fu KI, Sano Y, Kato S, Fujii T, Nagashima F, Yoshino T, Okuno T, Yoshida S, Fujimori T. Chromoendoscopy using indigo carmine dye spraying with magnifying observation is the most reliable method for differential diagnosis between non-neoplastic and neoplastic colorectal lesions: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2004;36:1089-1093. |

| 14. | Su MY, Hsu CM, Ho YP, Chen PC, Lin CJ, Chiu CT. Comparative study of conventional colonoscopy, chromoendoscopy, and narrow-band imaging systems in differential diagnosis of neoplastic and nonneoplastic colonic polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2711-2716. |

| 15. | Sano Y, Ikematsu H, Fu KI, Emura F, Katagiri A, Horimatsu T, Kaneko K, Soetikno R, Yoshida S. Meshed capillary vessels by use of narrow-band imaging for differential diagnosis of small colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:278-283. |