INTRODUCTION

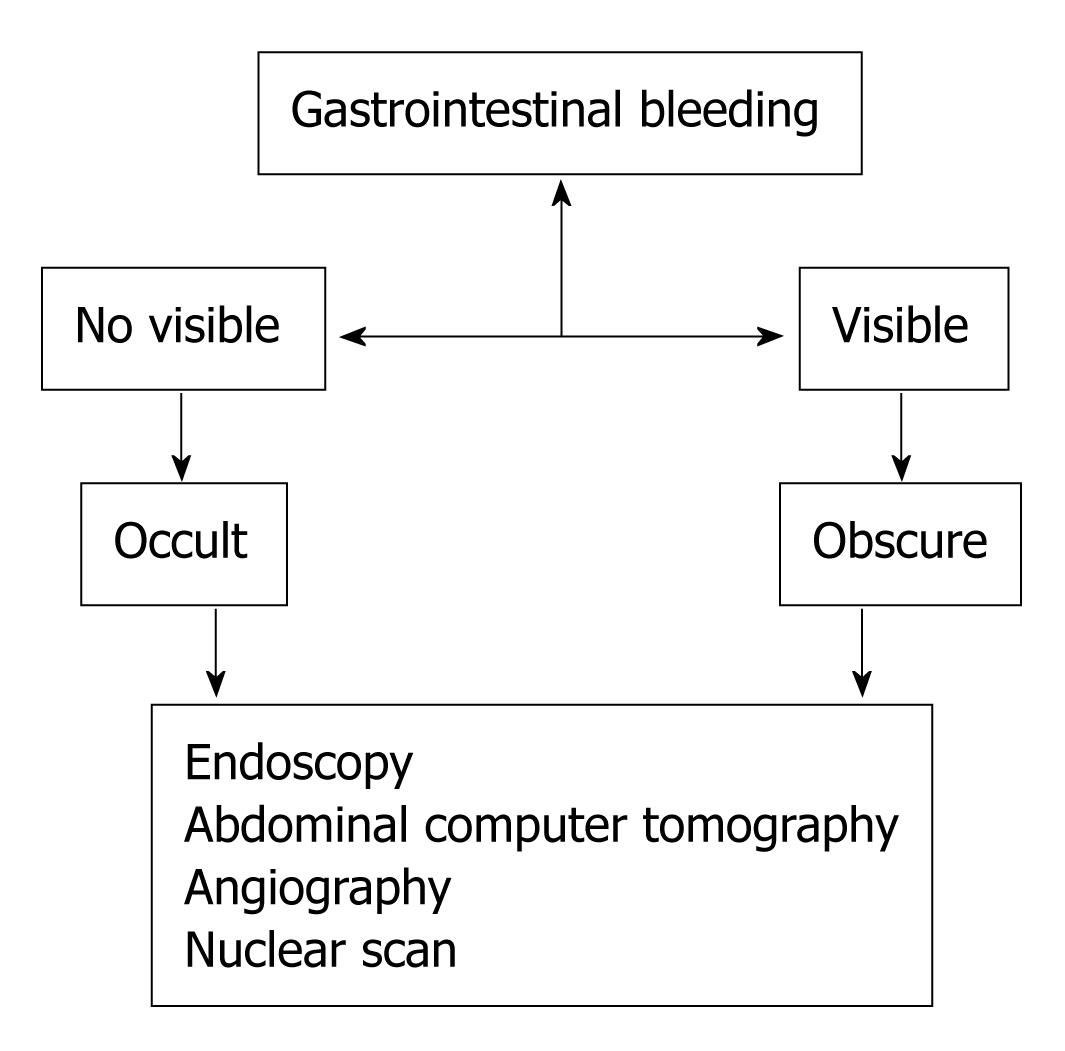

Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is a bleeding that starts in the gastrointestinal tract, which extends from the mouth to the large bowel. The amount of bleeding can range from nearly undetectable to acute, massive, and life threatening. The nearly undetectable gastrointestinal bleeding is a commonly encountered primary care clinical challenge but often the cause is occult or obscure[1,2]. Occult GIB is defined as bleeding that is not visible to the subject while obscure GIB is defined as persistent or recurrent bleeding for which no definitive source has been identified by an initial evaluation. Obscure GIB may be occult, if not visible or overt if it manifests with a continued passage of visible blood[3-5]. The causes and diagnostic approach of the occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) will be discussed in this editorial.

ETHIOLOGY

The evaluation of OGIB consists on a judicious search of the cause of bleeding, which should be guided by the clinical history and physical findings.

There are several elements on the medical history and physical examination that can provide clues about the cause of OGIB and help define the aggressiveness with which a bleeding site should be sought. A history can reveal ingestion of medications known to cause bleeding (e.g. aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anticoagulants). A family history might suggest a hereditary vascular problem. Other rare causes of bleeding may be detected on physical examination, including Plummer-Vinson syndrome, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and other diseases with typical cutaneous manifestations[6,7]. A family history of cancer occurring at an early age, particularly colorectal or endometrial, may suggest the presence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Their relative frequency has not been well defined in large trials but probably depends upon age[8]. Subjects younger than 40 may be more likely to have inflammatory bowel disease, a Meckel’s diverticulum, Dieulafoy’s lesion, or a small bowel tumor while older patients may be more likely to have bleeding from vascular lesions, erosions, or ulcers related to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. OGIB may have an upper (oesophagus, stomach), middle (small intestine) or lower tract (colon, rectum) source and may be of different nature. Causes of obscure or occult gastrointestinal bleeding: (1) Upper tract source: Esophagus/stomach: Reflux esophagitis, Erosive gastritis/ulceration, Varices, Cameron’s erosions within a hiatal hernia, Dieulafoy’s lesion, Gastric antral vascular ectasia; Portal gastropathy Small intestine: Duodenitis, Celiac sprue, Meckel’s diverticulum, Crohn’s disease; (2) Lower tract source: Colon: Diverticula, Ischemic colitis, Ulcerative colitis, other colitis, infection (e.g. hookworm, whipworm, Strongyloides, ascariasis, tuberculous enterocolitis, amebiasis, cytomegalovirus); (3) Rectum: Fissure, Hemorrhoids; (4) Any gastrointestinal source: Vascular ectasia/angiodysplasia, Carcinoma, Vasculitis, Aortoenteric fistula, Kaposi’s sarcoma, lymphoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, carcinoid tumors, Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, Amyloidosis, anti-inflammatory drugs, Radiation-induced mucosal injury; and (5) No source found. Recurrent hematemesis indicates bleeding above the ligament of Treitz while recurrent passage of bright red blood per rectum or melena suggests a lower GI cause. however OGIB is usually asymptomatic and occurs only with a positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT) and/or iron deficiency anemia, without visible fecal blood. Iron deficiency anemia, the result of chronic blood loss, is the most common form of anemia encountered in the world.

DIAGNOSIS

Iron deficiency anemia is most common in children and women of child-bearing age and/or who have become pregnant. From the perspective of the gastrointestinal tract, current dogma is that in men and postmenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia, gastrointestinal tract pathology is the likely source of blood loss, and that is where evaluation is generally focused. The diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia should be considered any time that a low serum hemoglobin level or hematocrit is encountered. A reduced mean corpuscular volume supports the diagnosis, but is not definitive. Iron deficiency anemia is best confirmed by documenting a low serum ferritin level. Celiac disease is an important cause of iron deficiency anemia and merits special consideration. It can lead not only to malabsorption of iron, but may also cause occult bleeding and should be ruled out in most patients with iron deficiency anemia. A high index of suspicion is often required to make the diagnosis; therefore, small bowel biopsies should be routinely obtained in patients without another obvious cause of iron deficiency anemia. Gastritis, either of the atrophic variety, or caused by Helicobacter pylori may be an important cause of iron deficiency anemia, presumably due to iron malabsorption. Many patients with iron deficiency anemia have no identifiable gastrointestinal tract abnormality after appropriate gastrointestinal evaluation (Figure 1). In this circumstance, explanations for iron deficiency anemia include non-gastrointestinal blood loss, misdiagnosis of the type of anemia, missed lesions, or nutritional deficiency. It is normal to lose 0.5-1.5 mL of blood daily in the gastrointestinal tract, and melena usually is identified when more than 150 mL of blood are lost in the upper gastrointestinal tract. The potential frequency of occult gastrointestinal bleeding is emphasized by the observation that approximately 150-200 mL of blood must be placed in the stomach to consistently produce visible evidence of blood in the stool. Subjects with gastroduodenal bleeding of up to 100 mL per day may have normal appearing stools. Thus, occult bleeding is often only identified by special tests that detect fecal blood, or, if bleeding occurs for a long enough period of time, it may become manifest by iron depletion and anemia[9]. FOBTs have sufficient sensitivity to detect bleeding that is not visible in the stool. There are three classes of FOBTs: guaiac-based tests, heme-porphyrin tests, and immunochemical tests. The standard approach to patients with OGIB is to directly evaluate the gastrointestinal tract. The best approach is to examine the gastrointestinal tract with endoscopy[10,11]. The major advantages of endoscopy versus other diagnostic approaches are that endoscopy is relatively safe and that biopsy and endoscopic therapy can be performed. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy is the best test in the evaluation of upper gastrointestinal tract while colonoscopy is the best in the examinations of colon. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) can identify lesions that endoscopy has failed to detect, in particular neoplastic mass lesions. However, CT is insensitive for detection of mucosal lesions[12]. Angiography (a technique that uses dye to highlight blood vessels) can be useful in situations when the patient is acutely bleeding such that dye leaks out of the blood vessel and identifies the site of bleeding. In selected situations, angiography allows injection of medicine into arteries that may stop the bleeding. Angiography may be useful in patients with active bleeding greater than 0.5 mL per minute and can identify highly vascular non-bleeding lesions such as angiodysplasia and neoplasms. Radionuclide scanning (a non-invasive screening technique) can be used for locating sites but of acute bleeding, especially in the lower GI tract. This technique involves injection of small amounts of radioactive material. Then, a special camera produces pictures of organs, allowing the doctor to detect a bleeding site. Radioisotope bleeding scans may be helpful in identifying the site of bleeding if the volume is greater than 0.1-0.4 mL per minute. However, positive findings in this type of testing must be verified with an alternative test because of a relatively high number of false-positive results. Sometimes, routine radiographic tests can be used (barium enema, upper gastrointestinal series), though these have fallen out of favour[13]. Radiographic studies are effective for detecting masses and large ulcerating lesions, but are not very accurate at detecting mucosal lesions. The small intestine is important to consider as a potential site of bleeding in patients with negative examinations of the colon and upper gastrointestinal tract. A number of approaches can be used to examine the small intestine. Endoscopic evaluation of the small intestine (known as push enteroscopy) has a greater sensitivity for mucosal abnormalities and possibly for mass lesions as well, and therefore has achieved a central position in evaluation of patients who do not present findings in the colon or upper gastrointestinal tract. Push enteroscopy consists of insertion of a long endoscope, usually a specialized enteroscope, and should be the initial approach in most patients[14,15]. Using conscious sedation, the enteroscope can be passed 50-60 cm beyond the ligament of Trietz, allowing examination of the distal duodenum and proximal jejunum. Push enteroscopy has been reported to identify a source of bleeding in approximately 25% of patients. More recently, “balloon” enteroscopy has been developed. This form of enteroscopy allows deeper insertion of the endoscope into the small bowel, and thus a larger portion of the bowel can be examined. However, the pathologies of the small bowel are notoriously difficult to diagnose so these techniques are often unsatisfactory for the identification of small bowel lesions. A new painless technique for endoscopic imagining of the small bowel has been recently suggested: the capsule endoscopy[16-18]. It consists of a swallowable capsule which acquires video images while moving through the gastrointestinal tract propelled by natural peristalsis until it is excreted. The capsule obtains at least 2 images per second, transmitting this data to a recording device worn by the patient. The data are subsequently downloaded to a computer workstation loaded with software that allows images to be analyzed. The video capsule endoscopy is not helpful for the study of some digestive tracts and, in fact it passes too quickly through the esophagus, and the stomach, with its large lumen, and these sites cannot be completely imaged. Moreover sometimes the capsule fails to reach the colon during the acquisition time. Recently, a capsule colonoscopy, in which patients swallow a small video capsule that then examines the colon, was presented[19]. The video capsule is able to evaluate almost all of the small bowel and this is an interesting finding[20-23]. In some trials this wireless endoscope system was found to be much better than radiographs and push endoscopy for evaluation of small bowel disease[24,25]. The propulsion of the capsule depends only on peristalsis, which is variable and sometimes too fast, so an eventual pathology can be seen on a single or few frames only. New methods should be devised to move the capsule, to increase its control, to determine its real location and to do direct biopsy or cauterisation. In our experience[26,27] the video capsule endoscopy, used in patients with intestinal bleeding of obscure etiology but of suspected jejuno-ileal origin, was well tolerated, able to acquire good images and identified lesions particularly if performed early after the bleeding. This new approach to the study of the small bowel is an important innovation for patients with disease of this tract of gut, particularly for those subjects with high surgical risk, however video capsule endoscopy technique should be improved in order to reduce the above said flaws. Intraoperative endoscopy can be used to examine the small bowel when other techniques fail to detect a bleeding source, but surgery itself has attendant increased risk and does not always add to the diagnosis. Surgical manipulation can create artifacts that may be mistaken for bleeding lesions. Intraoperative methods have determined a source of occult bleeding in up to 40% of undiagnosed cases, but they examine only 50%-80% of the small bowel[28-30].

Figure 1 Schema of evaluation occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding.

CONCLUSION

The source of OGIB can be identified in 85%-90%, no bleeding sites will be found in about 5%-10% of cases[1,2]. Even if the bleedings originating from the small bowel are not frequent in clinical practice (7.6% of all digestive haemorrhages, in our casuistry), they are notoriously difficult to diagnose. In spite of progress, however, a number of OGIB still remain problematic to deal with at present in the clinical context for both the difficulty in exactly identifying the site and nature of the underlying source and the difficulty in applying affective and durable diagnostic approach so no single technique has emerged as the most efficient way to evaluate OGIB. Most patients will benefit from careful evaluation that includes the evaluation of all gastrointestinal tracts. For some patients, this may mean multiple procedures. Additional studies are needed to clearly identify the most efficient approach to evaluation and definitive diagnosis of OGIB.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Jesús García-Cano, PhD, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital Virgen de la Luz, Cuenca 16002, Spain; Jamie S Barkin, MD, Professor of Medicine, Chief, Division of Gastroenterology & Active Attending Staff, Mt. Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, FL 33154, United States

S- Editor Li JL L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Ma WH