Published online Dec 8, 2016. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i34.1502

Peer-review started: July 13, 2016

First decision: August 26, 2016

Revised: September 16, 2016

Accepted: October 22, 2016

Article in press: October 24, 2016

Published online: December 8, 2016

Processing time: 147 Days and 1.4 Hours

To evaluate the outcome of patients with bilobar colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) and identify clinico-pathological variables that influenced survival.

Patients with bilobar CRLM were identified from a prospectively maintained hepatobiliary database during the study period (January 2010-June 2014). Collated data included demographics, primary tumour treatment, surgical data, histopathology analysis and clinical outcome. Down-staging therapy included Oxaliplatin- or Irinotecan- based regimens, and Cetuximab was also used in patients that were K-RAS wild-type. Response to neo-adjuvant therapy was assessed at the multi-disciplinary team meeting and considered for surgery if all macroscopic CRLM were resectable with a clear margin while preserving sufficient liver parenchyma.

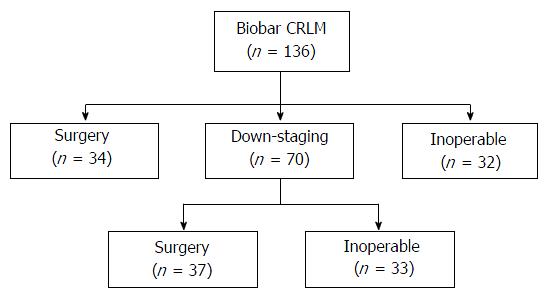

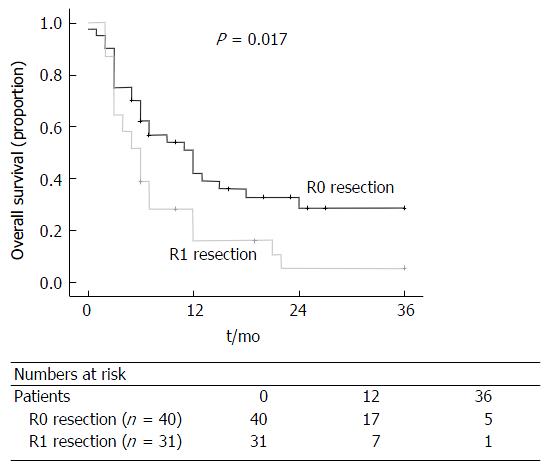

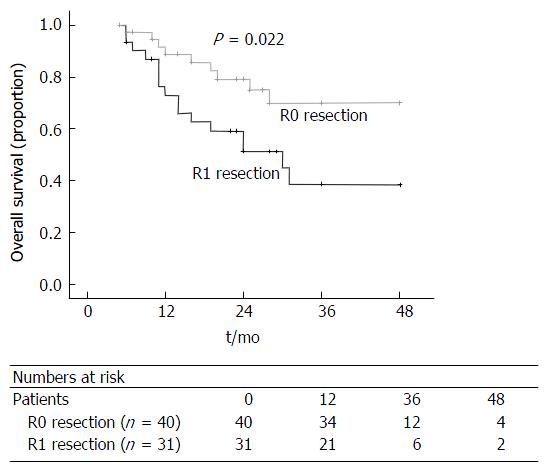

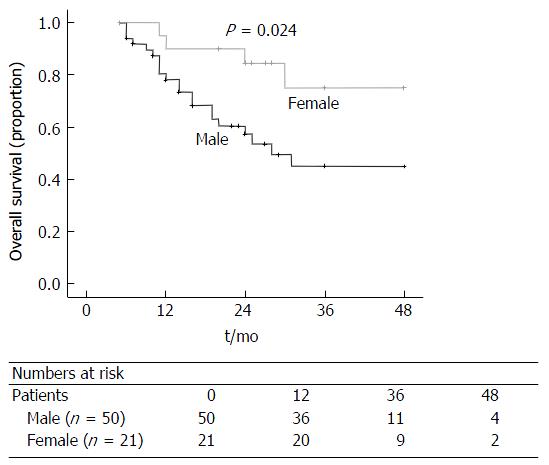

Of the 136 patients included, thirty-two (23.5%) patients were considered inoperable and referred for palliative chemotherapy, and thirty-four (25%) patients underwent liver resection. Seventy (51.4%) patients underwent down-staging therapy, of which 37 (52.8%) patients responded sufficiently to undergo liver resection. Patients that failed to respond to down-staging therapy (n = 33, 47.1%) were referred for palliative therapy. There was a significant difference in overall survival between the three groups (surgery vs down-staging therapy vs inoperable disease, P < 0.001). All patients that underwent hepatic resection, including patients that had down-staging therapy, had a significantly better overall survival compared to patients that were inoperable (P < 0.001). On univariate analysis, only resection margin significantly influenced disease-free survival (P = 0.017). On multi-variate analysis, R0 resection (P = 0.030) and female (P = 0.036) gender significantly influenced overall survival.

Patients undergoing liver resection with bilobar CRLM have a significantly better survival outcome. R0 resection is associated with improved disease-free and overall survival in this patient group.

Core tip: The management of colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) has evolved over the last decade. More patients are being subjected to potentially curative liver resection following down-staging therapy and the introduction of specialist multi-disciplinary team meetings. The introduction of biological agents has also increased resection rates. The current study analysed patients with bilobar CRLM referred to our centre. Patients that underwent liver resection had a significantly better survival outcome following our multi-disciplinary approach.

- Citation: Di Carlo S, Yeung D, Mills J, Zaitoun A, Cameron I, Gomez D. Resection margin influences the outcome of patients with bilobar colorectal liver metastases. World J Hepatol 2016; 8(34): 1502-1510

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v8/i34/1502.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i34.1502

Hepatic resection is the only potentially curative treatment for patients with colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) and the 5-year survival rate is up to 50%[1,2]. Patients with extensive, bilateral disease present a surgical challenge in removing all macroscopic disease while preserving sufficient functional liver remnant. Studies have shown that 20%-30% of all patients with CRLM are resectable at the time of diagnosis[3], with bilobar distribution of metastases a major contributing factor for unresectability[4].

More recently, the introduction of biological agents and the improved efficacy of down-staging chemotherapy regimens to treat bilobar CRLM have increased the proportion of patients with initially unresectable disease to subsequently operable disease. In addition, neo-adjuvant chemotherapy can potentially treat systemic disease to lower the risk of distant spread, and allow the identification of patients with biologically aggressive tumours that progress on chemotherapy that would not benefit from liver surgery[5]. Down-staging chemotherapy regimens are more toxic than palliative regimens, and hence, it is essential that there is multi-disciplinary team approach in determining the management plan for these patients[6]. However, long term outcomes for these patients following down-staging therapy and liver resection are indeterminate.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of patients with bilobar CRLM following multi-disciplinary therapy. The secondary aim was to identify clinico-pathological variables that influenced disease-free and overall survival in this group of patients.

Patients with bilobar CRLM were identified from a prospectively maintained hepatobiliary database at Queen’s Medical Centre (QMC), Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, Nottingham, United Kingdom during a 4-year period from January 2010 to June 2014. QMC is a tertiary referral center for Nottinghamshire and surrounding regions located in the north of East Midlands, United Kingdom. Pre-operative radiological assessment included a computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver. Patients with indeterminate lesions, in particular lung nodules, and patients with synchronous presentation underwent a positron emission tomography scan. Synchronous presentation was defined as the presence of liver metastases when colorectal cancer was diagnosed. Prior to any treatment, all patients including patients referred from the surrounding regions were discussed in a specialist multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting consisting of hepatobiliary surgeons, hepatologists, oncologists, radiologists and pathologists. Patients were selected for liver resection without any prior neo-adjuvant therapy if all macroscopic CRLM were resectable to achieve a clear margin while preserving sufficient liver parenchyma.

Collated data included patient demographics, type of surgical resection, histopathology analysis and clinical outcome. This study has been registered and approved by the Clinical Audit Department, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust. Since this is a retrospective study, individual patient consent was not required, and all local ethical guidelines with respect to retrospective studies in this Trust were adhered to.

Patients scheduled for preoperative systemic chemotherapy had 3-6 mo of neo-adjuvant treatment. The regimens used were either Oxaliplatin based: Two weekly FOLFOX [5-fluorouracil (FU) 400 mg/m2 bolus, and 2400 mg/m2 over 46 h, Leucovorin and Oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2] or three weekly CAPOX (Capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 BD for 14 d and Oxaliplatin 130 mg/ m2).

However, in patients tested and found to be K-RAS wild-type, two weekly FOLFIRI (Irinotecan 180mg/m2, 5-FU 400 mg/m2 bolus, and 2400 mg/m2 over 46 h) was administered with concurrent Cetuximab (400 mg/m2 cycle 1, then 250 mg/m2 cycle 2 onwards).

The response to neo-adjuvant therapy was assessed after 3-6 mo of therapy by CT scan and repeat MRI of the liver if required. Patients were then re-discussed at the MDT and considered for surgery based on absence of new disease, tumour response and extent of disease. Patients deemed to have resectable disease were scheduled for a liver resection, 4-6 wk after their last cycle of chemotherapy. Resectable disease was defined as excision of all macroscopic CRLM to achieve a clear margin while preserving sufficient liver parenchyma based on pre-operative radiological imaging.

Following liver resection, chemotherapy was considered in patients with tumour present at the margin (R1 resection).

Liver resection was performed using the Cavi-Pulse Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator. Intra-operative ultrasound was performed to confirm the findings of pre-operative imaging and to assist in surgical planning. The number of hepatic Couinaud’s[7] segments resected was determined by the procedure performed as stated in the Brisbane nomenclature[8]. Type of surgical procedure was dependent on the resection of all macroscopic disease and achieving a clear resection margin, while preserving sufficient remnant liver. The extent of hepatic resection in this study was classified into two groups; less than hemi-hepatectomy and hemi-hepatectomy or more radical resection. Pre-operative PVE was performed if the FRL volume was estimated to be 20% or less of the total liver volume. Liver-first approach was defined when the hepatic resection was performed first prior to colonic or rectal resection[9,10].

In patients where the liver-first approach was adopted, primary tumour resection was usually scheduled 4-8 wk following liver resection, or after completion of chemo-radiotherapy for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. All patients underwent re-staging with a CT scan and MRI to ensure there was no evidence of liver recurrence or distant metastases. Colorectal resection was performed according to accepted oncological standards, with complete meso-rectal excision for rectal cancers and lymph node dissection for colonic cancers.

Histopathological data of the resected liver specimen were collated. This included: Tumour size in maximum diameter; tumour number; and status of resection margin. R0 resection was defined as no microscopic evidence of tumour at or within 1 mm of the margin. Lymphatic, peri-neural, biliary and vascular invasion were also determined[11].

Patients were followed up in specialist hepatobiliary clinics. Following initial post-operative review at one month, all patients were examined in the outpatient clinic at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 mo and annually thereafter. At each clinical review, carcino-embryonic antigen levels were measured. All patients in this study had a minimum follow-up of 6 mo following hepatic resection for CRLM.

Surveillance imaging included CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis. Patients underwent 6-monthly CT scan during the first two post-operative years, followed by annual CT scans thereafter. Liver MRI was used to characterise suspicious hepatic lesions demonstrated on CT. Development of symptoms of recurrence at any time-point prompted earlier review than scheduled.

Overall and disease-free survival was recorded, with disease-free survival being defined as the time from primary hepatic resection to the first documented disease recurrence on imaging. Overall survival was defined as the time interval between the date of commencement of neo-adjuvant/induction therapy and the date of death or most recent date of follow-up if the patient was still alive. Following detection of recurrent disease on surveillance imaging, all patients were discussed at the MDT meeting. Patients who had non-resectable disease were referred to the oncologists for consideration of palliative chemotherapy.

Categorical data was presented as frequency and percentage. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to assess the actuarial survival and disease-free survival, and presented as median (range). Univariate analysis was performed to assess for a significant difference in clinico-pathological characteristics that influenced disease recurrence and survival. A multivariate analysis was performed by Cox regression (Step-wise forward model) for variables significant on univariate analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS for Windows™ version 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill, United States), and statistical significance was taken at the 5% level. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed and performed by Gomez D, QMC, Nottingham, United Kingdom.

During the study period, a total of 136 patients (Table 1) with bilobar CRLM were discussed in the unit’s MDT, of which 34 (25.0%) patients underwent surgery with curative intent as their primary treatment (Figure 1). There were 32 (23.5%) patients that had extensive disease and were referred for palliative therapy.

| Demographic, clinical and pathological factors | Total (n) |

| All patients (n = 136) | |

| All surgery patients (n = 71) | |

| Demographic factors | |

| Age > 65 yr | 68 |

| Male gender | 99 |

| Synchronous presentation | 80 |

| Down-staging therapy | 70 |

| Oxaliplatin-based regimen | 60 |

| Irinotecan-based regimen | 10 |

| Addition of biological agent | 30 |

| Surgical factors (n = 71) | |

| Hemi-hepatectomy or more | 22 |

| Histo-pathological factor (n = 71) | |

| Largest tumour size ≥ 5 cm | 11 |

| Number of metastases < 4 | 44 |

| Lymphatic invasion present | 15 |

| Vascular invasion present | 28 |

| Peri-neural invasion present | 9 |

| Biliary invasion present | 25 |

| Resection margin (R0) | 40 |

Seventy (51.4%) patients were considered for down-staging therapy, in view to consider liver resection depending on response to therapy. Besides receiving either an Oxaliplatin-based (n = 60) or Irinotecan-based (n = 10) regimen, 30 (42.8%) patients also had biological agents as part of their down-staging treatment. Within the group of patients that received down-staging therapy, 37 (52.8%) patients had a response to their down-staging therapy and underwent hepatic resection, while the remaining patients [n = 33 (47.2%)] did not undergo surgical resection. These patients did not respond to their down-staging therapy, which included: (1) having new metastases; (2) disease progression; and (3) inability to remove all macroscopic liver disease whilst leaving sufficient remnant liver. This decision was based on MDT review of up to date radiological imaging following down-staging therapy.

Overall, there were 71 (52.2%) patients that underwent liver resection, of which twenty-two patients had a hemi-hepatectomy or more. The most common surgical procedures performed was multiple non-anatomical resections (n = 40, 56.3%). Twenty-one patients were female and the median age at the diagnosis was 65 (range: 44-84) years. Seven (9.8%) patients had portal vein embolization prior to liver resection. There were 35 patients with synchronous disease, of which 17 patients had a liver-first approach. There was no post-operative mortality.

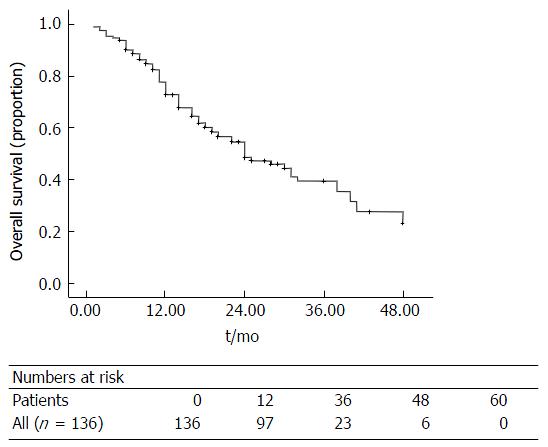

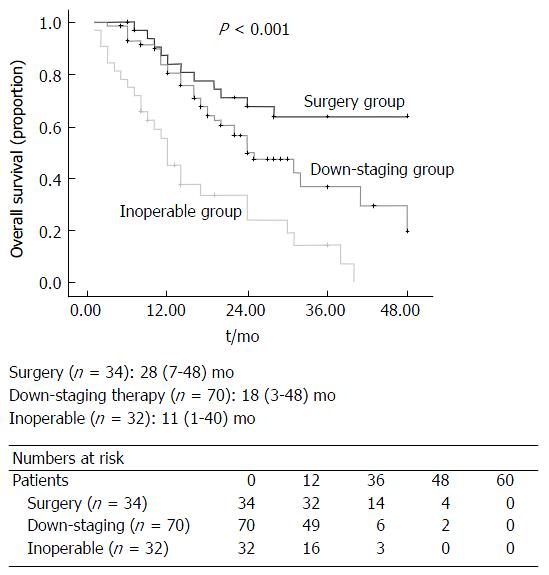

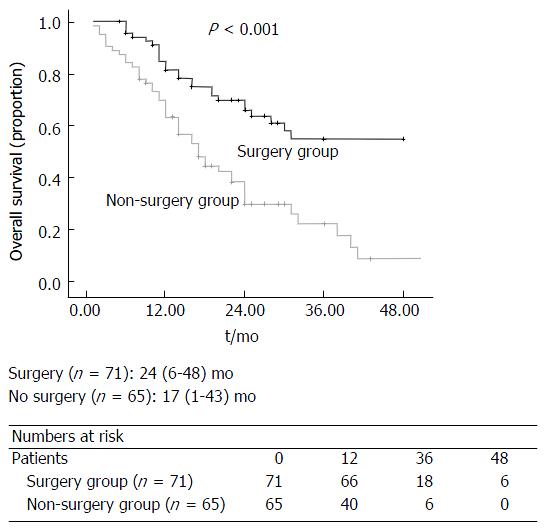

The median overall survival for all patients in this study was 18 (1-48) mo (Figure 2). There was a significant difference in overall survival between the three groups (Surgery vs Down-staging therapy vs Inoperable disease, P < 0.001; Figure 3). All patients that underwent hepatic resection, including patients that had down-staging therapy, had a significantly better overall survival compared to patients that were inoperable [24 (6-48) mo vs 17 (1-43) mo; P < 0.001; Figure 4]. The disease-free survival for patients that underwent liver resection was 8 (range: 2-36) mo.

With respect to disease-free survival, patients with a clear (R0) resection margin following liver resection had a significantly better disease-free survival compared to patients with a R1 resection (P = 0.017; Table 2 and Figure 5).

| Demographic, clinical and pathological factors | Survival [median (range) mo] | Uni-variate analysis |

| Demographic factors | ||

| Age | 0.099 | |

| < 65 yr (n = 43) | 6 (3-36) | |

| ≥ 65 yr (n = 28) | 12 (2-36) | |

| Gender | 0.343 | |

| Male (n = 50) | 6 (3-36) | |

| Female (n = 21) | 5 (2-36) | |

| Presentation | 0.755 | |

| Synchronous (n = 35) | 6 (2-36) | |

| Metachronous (n = 36) | 6 (3-36) | |

| Surgical factors | ||

| Less than hemi-hepatectomy (n = 49) | 6 (2-36) | 0.760 |

| Hemi-hepatectomy or more (n = 22) | 6 (2-36) | |

| Histo-pathological factor | ||

| Largest tumour size | 0.813 | |

| < 5 cm (n = 60) | 6 (2-36) | |

| ≥ 5 cm (n = 11) | 9 (2-36) | |

| No. of metastases | 0.538 | |

| < 4 (n = 44) | 7 (2-36) | |

| > 5 (n = 27) | 6 (3-36) | |

| Lymphatic invasion | 0.256 | |

| Positive (n = 15) | 6 (2-24) | |

| Negative (n = 56) | 6 (2-36) | |

| Vascular invasion | 0.775 | |

| Positive (n = 28) | 6 (2-36) | |

| Negative (n = 43) | 7 (2-36) | |

| Peri-neural invasion | 0.115 | |

| Positive (n = 9) | 6 (2-24) | |

| Negative (n = 62) | 6 (2-36) | |

| Biliary invasion | 0.919 | |

| Positive (n = 25) | 6 (2-36) | |

| Negative (n = 46) | 6 (2-36) | |

| Resection margin (R0) | 0.017 | |

| R0 (n = 40) | 8 (2-36) | |

| R1 (n = 31) | 6 (2-36) |

Patients with a R0 resection (P = 0.022; Figure 6) and female gender (P = 0.024; Figure 7) has a significantly better overall survival compared to patients with a R1 resection and male gender on univariate analysis. On the multi-variate analysis, both R0 resection and female gender were independent predictors of improved overall survival (Table 3).

| Demographic, clinical and pathological factors | Survival [median (range) mo] | Uni-variate analysis | Multi-variate analysis | Risk ratio (confidence interval) |

| Demographic factors | ||||

| Age | 0.173 | |||

| < 65 yr (n = 43) | 20 (6-48) | |||

| ≥ 65 yr (n = 28) | 27 (7-48) | |||

| Gender | 0.024 | 0.036 | 3.172 (1.079-9.327) | |

| Male (n = 50) | 19 (6-48) | |||

| Female (n = 21) | 20 (11-48) | |||

| Presentation | 0.932 | |||

| Synchronous (n = 35) | 23 (6-48) | |||

| Metachronous (n = 36) | 24 (6-48) | |||

| Surgical factors | ||||

| Less than hemi- hepatectomy (n = 49) | 22 (6-48) | 0.947 | ||

| Hemi-hepatectomy or more (n = 22) | 28 (7-48) | |||

| Histo-pathological factor | ||||

| Largest tumour size | 0.216 | |||

| < 5 cm (n = 60) | 24 (6-48) | |||

| ≥ 5 cm (n = 11) | 28 (12-48) | |||

| Number of metastases | 0.674 | |||

| < 4 (n = 44) | 24 (6-48) | |||

| > 5 (n = 27) | 24 (11-48) | |||

| Lymphatic invasion | 0.943 | |||

| Positive (n = 15) | 24 (11-48) | |||

| Negative (n = 56) | 23 (6-48) | |||

| Vascular invasion | 0.367 | |||

| Positive (n = 28) | 25 (6-48) | |||

| Negative (n = 43) | 23 (6-48) | |||

| Peri-neural invasion | 0.220 | |||

| Positive (n = 9) | 12 (11-48) | |||

| Negative (n = 62) | 24 (6-48) | |||

| Biliary invasion | 0.608 | |||

| Positive (n = 25) | 27 (11-48) | |||

| Negative (n = 46) | 22 (6-48) | |||

| Resection margin (R0) | 0.022 | 0.030 | 0.403 (0.178-0.917) | |

| R0 (n = 40) | 24 (6-48) | |||

| R1 (n = 31) | 22 (6-48) |

With the improvement in chemotherapy agents and the increased efficacy with the addition of biological agents, many centers have reported an increased number of patients being converted from initially unresectable, to resectable disease[12,13]. However, although there are an increased number of patients undergoing liver resection with curative intent, some authorities may suggest that these patients are unlikely to be cured[14]. Nevertheless, these patients have a better overall survival in comparison to patients treated with palliative systemic chemotherapy, with some authors reporting a median survival up to 45 mo[12,15]. In the present study, patients with bilobar disease who underwent surgery had a significantly better overall survival compared to patients who failed down-staged chemotherapy and/or treated with palliative chemotherapy.

The addition of biological agents to current Oxaliplatin- and Irinotecan- based regimens has led to further improvements in response rates. In a large randomised control trial, Folprecht et al[16] showed an increased response rate up to 68% with the addition of Cetuximab. Similarly, Masi et al[17] observed that the addition of Bevacizumab to Oxaliplatin- and Irinotecan- based regimens increased the response rate up to 80%. In the present study, the unit’s down-staging therapy protocol had a response rate and a conversion of unresectable to resectable disease of more than 50%. These results were consistent with data reported by the groups of Van Custem et al[18] and Bokemeyer et al[19] that observed a conversion rate of approximately 60% following down-staging chemotherapy.

Adam et al[13] recently published their long-term survival results following down-sizing chemotherapy and hepatic resection in patients with CRLM and demonstrated that 24 (16%) of 148 patients were alive and disease-free with a minimum of 5-year follow-up. Several studies have shown the improvements in survival after the addition of anti-VEGF/EGFR[20-22]. Recently, a number of case series describing 10-year actual survivors after liver resection of CRLM have been published[23,24]. The present series demonstrated that hepatic resection for patients with bilobar CRLM had a median disease-free and overall survival of 8 and 24 mo, respectively.

Definitions of resectable disease have evolved over time, with current consensus suggesting that disease should be considered technically resectable as long as complete macroscopic resection is feasible, whilst maintaining sufficient future liver volume[25]. However, there remains concern that not all patients with technically resectable liver-limited metastases benefit from surgery; with approximately half of these patients will develop recurrences within three years of liver resection[26]. Therefore, it is crucial that the decision-making process around treatment strategies for metastatic colorectal cancer are made in a MDT environment that consists of specialist hepato-biliary surgeons, radiologists and oncologists that can define optimal patient management on a case by case basis. A recent study demonstrated that almost two-thirds of patients with tumours deemed unresectable by non-specialists were considered potentially resectable by a panel of specialist hepato-biliary surgeons based on radiological imaging[27].

The role of margin status as a predictor of outcome following resection for CRLM is controversial. Bodingbauer et al[28] observed that resection margin and size of margin width did not correlate significantly with survival following resection for CRLM. In a series of 1019 patients, and co-investigators demonstrated that a resection margin > 1 cm was an independent predictor of survival following resection for CRLM[29]. Rees et al[1] also demonstrated that positive resection margins were an independent predictor of poorer survival. However, Figueras et al[30] showed that a margin width < 1 cm in patients who underwent resection for CRLM did not significantly influence recurrent disease in a cohort of 609 patients. Homayounfar et al[31] demonstrated that R0 resection in patients with bilobar CRLM have improved survival rates following multi-modal therapy[32]. In the present series, a clear resection margin, defined as no microscopic evidence of tumour at or within 1 mm of the margin, was an independent predictor of both disease-free and overall survival. Due to the differences in results observed with respect to resection margin between published studies, it may be that only a selected group of patients undergoing resection for CRLM are influenced by a clear margin. In the present series that focused on patients with bilobar CRLM, that would be considered as having a high tumour burden, benefited from a R0 margin. This could be due to the fact that these patients have an aggressive tumour profile and it is crucial that complete tumour clearance is obtained. Hence, for these patients, “down-sizing” chemotherapy should certainly be considered prior to resection to aid in achieving a clear resection margin. Furthermore, many groups advocate a trial of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with a high tumour burden, as disease progression on chemotherapy would be a contraindication to surgery[33]. Nevertheless, with the increase use of chemotherapy, there is an increase in prevalence of patients undergoing hepatic resection with a background of chemotherapy-related injury, such as steato-hepatitis[34] and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome[35]. In such cases, the quality, rather than quantity of the remnant liver becomes an important issue to consider prior to extensive resection.

The present study also showed that female gender was an independent prognostic factor for improved overall survival. There are currently no other studies that have reported this finding.

There are limitations in this study. This is a retrospective study, and focused on a group of patients with bilobar liver metastases. These are patients with bad tumour biology and in most cases, will require down-staging therapy. Nevertheless, although these group of patients have a higher tumour burden; their prognosis can be improved with a MDT approach that focuses on multi-modal therapy.

Patients with bilobar CRLM treated with liver resection as a primary treatment or following down-staging therapy have a better overall survival compared to patients who failed down-staging therapy and/or treated with palliative chemotherapy. Obtaining a clear resection margin in these cases significantly influences outcome. In this group of patients, multi-modal therapy is crucial to achieve a better survival outcome.

Hepatic resection is the only potentially curative treatment for patients with colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) and the 5-year survival rate is up to 50%.

The introduction of biological agents and the improved efficacy of down-staging chemotherapy regimens to treat bilobar CRLM have increased the proportion of patients with initially unresectable disease to subsequently operable disease. In addition, neo-adjuvant chemotherapy can potentially treat systemic disease to lower the risk of distant spread, and allow the identification of patients with biologically aggressive tumours that progress on chemotherapy that would not benefit from liver surgery.

In the present study, patients with bilobar disease who underwent surgery had a significantly better overall survival compared to patients who failed down-staged chemotherapy and/or treated with palliative chemotherapy.

Patients with bilobar CRLM treated with liver resection as a primary treatment or following down-staging therapy have a better overall survival compared to patients who failed down-staging therapy and/or treated with palliative chemotherapy.

This article is interesting but I think epidemiological data are more interesting than univariate and multivariate analysis, which is the part highlighted by the authors. Structure of the manuscript is correct.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lorenzo D S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Rees M, Tekkis PP, Welsh FK, O’Rourke T, John TG. Evaluation of long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multifactorial model of 929 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:125-135. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 777] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 788] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Brouquet A, Abdalla EK, Kopetz S, Garrett CR, Overman MJ, Eng C, Andreou A, Loyer EM, Madoff DC, Curley SA. High survival rate after two-stage resection of advanced colorectal liver metastases: response-based selection and complete resection define outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1083-1090. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 293] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kanas GP, Taylor A, Primrose JN, Langeberg WJ, Kelsh MA, Mowat FS, Alexander DD, Choti MA, Poston G. Survival after liver resection in metastatic colorectal cancer: review and meta-analysis of prognostic factors. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:283-301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 263] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sakamoto Y, Fujita S, Akasu T, Nara S, Esaki M, Shimada K, Yamamoto S, Moriya Y, Kosuge T. Is surgical resection justified for stage IV colorectal cancer patients having bilobar hepatic metastases?--an analysis of survival of 77 patients undergoing hepatectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:784-788. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chun YS, Vauthey JN, Ribero D, Donadon M, Mullen JT, Eng C, Madoff DC, Chang DZ, Ho L, Kopetz S. Systemic chemotherapy and two-stage hepatectomy for extensive bilateral colorectal liver metastases: perioperative safety and survival. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1498-1504; discussion 1504-1505. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 126] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sutcliffe RP, Bhattacharya S. Colorectal liver metastases. Br Med Bull. 2011;99:107-124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Couinaud C. [Liver lobes and segments: notes on the anatomical architecture and surgery of the liver]. Presse Med. 1954;62:709-712. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Strasberg SM. Nomenclature of hepatic anatomy and resections: a review of the Brisbane 2000 system. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:351-355. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 656] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de Rosa A, Gomez D, Hossaini S, Duke K, Fenwick SW, Brooks A, Poston GJ, Malik HZ, Cameron IC. Stage IV colorectal cancer: outcomes following the liver-first approach. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108:444-449. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | De Rosa A, Gomez D, Brooks A, Cameron IC. “Liver-first” approach for synchronous colorectal liver metastases: is this a justifiable approach? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:263-270. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gomez D, Zaitoun AM, De Rosa A, Hossaini S, Beckingham IJ, Brooks A, Cameron IC. Critical review of the prognostic significance of pathological variables in patients undergoing resection for colorectal liver metastases. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:836-844. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lam VW, Spiro C, Laurence JM, Johnston E, Hollands MJ, Pleass HC, Richardson AJ. A systematic review of clinical response and survival outcomes of downsizing systemic chemotherapy and rescue liver surgery in patients with initially unresectable colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1292-1301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 128] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adam R, Wicherts DA, de Haas RJ, Ciacio O, Lévi F, Paule B, Ducreux M, Azoulay D, Bismuth H, Castaing D. Patients with initially unresectable colorectal liver metastases: is there a possibility of cure? J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1829-1835. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 422] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 400] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jones RP, Jackson R, Dunne DF, Malik HZ, Fenwick SW, Poston GJ, Ghaneh P. Systematic review and meta-analysis of follow-up after hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2012;99:477-486. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 125] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jones RP, Hamann S, Malik HZ, Fenwick SW, Poston GJ, Folprecht G. Defined criteria for resectability improves rates of secondary resection after systemic therapy for liver limited metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1590-1601. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Folprecht G, Gruenberger T, Bechstein WO, Raab HR, Lordick F, Hartmann JT, Lang H, Frilling A, Stoehlmacher J, Weitz J. Tumour response and secondary resectability of colorectal liver metastases following neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cetuximab: the CELIM randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:38-47. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 704] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 691] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Masi G, Loupakis F, Salvatore L, Fornaro L, Cremolini C, Cupini S, Ciarlo A, Del Monte F, Cortesi E, Amoroso D. Bevacizumab with FOLFOXIRI (irinotecan, oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and folinate) as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:845-852. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 201] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, D’Haens G, Pintér T, Lim R, Bodoky G. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408-1417. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2901] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3063] [Article Influence: 204.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, Hartmann JT, Aparicio J, de Braud F, Donea S, Ludwig H, Schuch G, Stroh C. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:663-671. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1218] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1211] [Article Influence: 75.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stintzing S, Fischer von Weikersthal L, Decker T, Vehling-Kaiser U, Jäger E, Heintges T, Stoll C, Giessen C, Modest DP, Neumann J. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer-subgroup analysis of patients with KRAS: mutated tumours in the randomised German AIO study KRK-0306. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1693-1699. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schwartzberg LS, Rivera F, Karthaus M, Fasola G, Canon JL, Hecht JR, Yu H, Oliner KS, Go WY. PEAK: a randomized, multicenter phase II study of panitumumab plus modified fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX6) or bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with previously untreated, unresectable, wild-type KRAS exon 2 metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2240-2247. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 448] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 478] [Article Influence: 47.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gomez D, De Rosa A, Addison A, Brooks A, Malik HZ, Cameron IC. Cetuximab therapy in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: the future frontier? Int J Surg. 2013;11:507-513. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Viganò L, Ferrero A, Lo Tesoriere R, Capussotti L. Liver surgery for colorectal metastases: results after 10 years of follow-up. Long-term survivors, late recurrences, and prognostic role of morbidity. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2458-2464. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Pulitanò C, Castillo F, Aldrighetti L, Bodingbauer M, Parks RW, Ferla G, Wigmore SJ, Garden OJ. What defines ‘cure’ after liver resection for colorectal metastases? Results after 10 years of follow-up. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:244-249. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Adam R, De Gramont A, Figueras J, Guthrie A, Kokudo N, Kunstlinger F, Loyer E, Poston G, Rougier P, Rubbia-Brandt L. The oncosurgery approach to managing liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Oncologist. 2012;17:1225-1239. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 393] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jones RP, Stättner S, Sutton P, Dunne DF, McWhirter D, Fenwick SW, Malik HZ, Poston GJ. Controversies in the oncosurgical management of liver limited stage IV colorectal cancer. Surg Oncol. 2014;23:53-60. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jones RP, Vauthey JN, Adam R, Rees M, Berry D, Jackson R, Grimes N, Fenwick SW, Poston GJ, Malik HZ. Effect of specialist decision-making on treatment strategies for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1263-1269. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bodingbauer M, Tamandl D, Schmid K, Plank C, Schima W, Gruenberger T. Size of surgical margin does not influence recurrence rates after curative liver resection for colorectal cancer liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1133-1138. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Are C, Gonen M, Zazzali K, Dematteo RP, Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, D’Angelica M. The impact of margins on outcome after hepatic resection for colorectal metastasis. Ann Surg. 2007;246:295-300. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 170] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Figueras J, Burdio F, Ramos E, Torras J, Llado L, Lopez-Ben S, Codina-Barreras A, Mojal S. Effect of subcentimeter nonpositive resection margin on hepatic recurrence in patients undergoing hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Evidences from 663 liver resections. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1190-1195. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Homayounfar K, Liersch T, Niessner M, Meller J, Lorf T, Becker H, Ghadimi BM. Multimodal treatment options for bilobar colorectal liver metastases. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395:633-641. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Homayounfar K, Bleckmann A, Conradi LC, Sprenger T, Beissbarth T, Lorf T, Niessner M, Sahlmann CO, Meller J, Becker H. Bilobar spreading of colorectal liver metastases does not significantly affect survival after R0 resection in the era of interdisciplinary multimodal treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1359-1367. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Viganò L, Capussotti L, Barroso E, Nuzzo G, Laurent C, Ijzermans JN, Gigot JF, Figueras J, Gruenberger T, Mirza DF. Progression while receiving preoperative chemotherapy should not be an absolute contraindication to liver resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2786-2796. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Vauthey JN, Pawlik TM, Ribero D, Wu TT, Zorzi D, Hoff PM, Xiong HQ, Eng C, Lauwers GY, Mino-Kenudson M. Chemotherapy regimen predicts steatohepatitis and an increase in 90-day mortality after surgery for hepatic colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2065-2072. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 970] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 937] [Article Influence: 52.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Rubbia-Brandt L, Audard V, Sartoretti P, Roth AD, Brezault C, Le Charpentier M, Dousset B, Morel P, Soubrane O, Chaussade S. Severe hepatic sinusoidal obstruction associated with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:460-466. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 752] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 736] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |