Published online Nov 8, 2016. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i31.1318

Peer-review started: May 29, 2016

First decision: July 29, 2016

Revised: August 19, 2016

Accepted: September 8, 2016

Article in press: September 9, 2016

Published online: November 8, 2016

Processing time: 159 Days and 4.6 Hours

To study impact of baseline mental health disease on hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment; and Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) changes with sofosbuvir- and interferon-based therapy.

This is a retrospective cohort study of participants from 5 studies enrolled from single center trials conducted at the Clinical Research Center of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States. All participants were adults with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection and naïve to HCV therapy. Two of the studies included HCV mono-infected participants only (SPARE, SYNERGY-A), and 3 included human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/HCV co-infected participants only (ERADICATE, PFINPK, and ALBIN). Patients were treated for HCV with 3 different regimens: Sofosbuvir and ribavirin in the SPARE trial, ledipasvir and sofosbuvir in SYNERGY-A and ERADICATE trials, and pegylated interferon (IFN) and ribavirin for 48 wk in the PIFNPK and ALBIN trials. Participants with baseline mental health disease (MHD) were identified (defined as either a DSM IV diagnosis of major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, generalized anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder or requiring anti-depressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers or psychotropics prescribed by a psychiatrist). For our first aim, we compared sustained virologic response (SVR) and adherence (pill counts, study visits, and in 25 patients, blood levels of the sofosbuvir metabolite, GS-331007) within each study. For our second aim, only patients with HIV coinfection were evaluated. BDI scores were obtained pre-treatment, during treatment, and post-treatment among participants treated with sofosbuvir-based therapy, and compared to scores from participants treated with interferon-based therapy. Statistical differences for both aims were analyzed by Fisher’s Exact, and t-test with significance defined as a P value less than 0.05.

Baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between all participants with and without MHD groups treated with sofosbuvir-based therapy. Among patients treated with sofosbuvir-based therapy, the percentage of patients with MHD who achieved SVR was the same as those without (SPARE: 60.9% of those MHD compared to 67.6% in those without, P = 0.78; SYNERGY-A: 100% of both groups; ERADICATE: 100% compared to 97.1%). There was no statistically significant difference in pill counts, adherence to study visits between groups, nor mean serum concentrations of GS-331007 for each group at week 2 of treatment (P = 0.72). Among patients with HIV co-infection, pre-treatment BDI scores were similar among patients treated with sofosbuvir, and those treated with interferon (sofosbuvir-based 5.24, IFN-based 6.96; P = 0.14); however, a dichotomous effect on was observed during treatment. Among participants treated with directly acting antiviral (DAA)-based therapy, mean BDI scores decreased from 5.24 (pre-treatment) to 3.28 during treatment (1.96 decrease, P = 0.0034) and 2.82 post-treatment. The decrease in mean score from pre- to post-treatment was statistically significant (-2.42, P = 0.0012). Among participants treated with IFN-based therapy, mean BDI score increased from 6.96 at pre-treatment to 9.19 during treatment (an increase of 2.46 points, P = 0.1), and then decreased back to baseline post-treatment (mean BDI score 6.3, P = 0.54). Overall change in mean BDI scores from pre-treatment to during treatment among participants treated with DAA-based and IFN-therapy was statistically significant (-1.96 and +2.23, respectively; P = 0.0032). This change remained statistically significant when analysis was restricted to participants who achieved SVR (-2.0 and +4.36, respectively; P = 0.0004).

Sofosbuvir-based therapy is safe and well tolerated in patients with MHD. A decline in BDI associated with sofosbuvir-based HCV treatment suggests additional MHD benefits, although the duration of these effects is unknown.

Core tip: The prevalence of mental health disease (MHD) among patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) can be high. However, patients with MHD may be marginalized with respect to HCV therapy and MHD is one of the most frequently cited reason for exclusion from HCV therapy. HCV therapy has evolved from interferon-based to directly acting antiviral (DAA)-based therapy with excellent tolerability and efficacy. Our study found that baseline MHD did not impact efficacy nor treatment adherence to sofosbuvir-based therapy. Furthermore, we found that Becks Depression Inventory scores improved with sofosbuvir-based therapy, suggesting that HCV treatment with the newer DAA therapies may have additional mental health benefits.

- Citation: Tang LSY, Masur J, Sims Z, Nelson A, Osinusi A, Kohli A, Kattakuzhy S, Polis M, Kottilil S. Safe and effective sofosbuvir-based therapy in patients with mental health disease on hepatitis C virus treatment. World J Hepatol 2016; 8(31): 1318-1326

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v8/i31/1318.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i31.1318

An estimated 185 million people worldwide are currently infected with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV), and approximately 3 to 4 million new infections occur each year[1]. Chronic infection with HCV is a leading cause of progressive liver disease, end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular cancer, and remains the leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States[2-4].

A complex interplay exists between mental health disorders (MHD) and HCV infection[5-9]. In some cohorts, 30%-44% of all patients with HCV have an active psychiatric-most frequently depression-disorder[7,10-14]. MHD is one of the most frequently cited reason for exclusion from HCV therapy, contributing to 44% of exclusions in one study[13]. Exacerbation of psychiatric complications, adherence, concurrent substance abuse, and concern for reinfection are just some of the barriers to treatment[5]. These concerns are primarily related to interferon-based therapies, which require long treatment durations of 24 to 48 wk, high pill burdens, and multiple associated dose-limiting neuropsychiatric side effects[8,14-16]. Recent reports, however, suggest that patients with MHD can successfully achieve sustained virologic response (SVR, considered cure) rates with interferon-based regimens comparable to those without MHD[8,14,17].

Treatment has shifted to combination all-oral, interferon-free directly acting antiviral (DAA) therapy characterized by short treatment durations of 8-24 wk[18-22], low pill burdens, improved tolerability, and achieving SVR rates of over 90% for both treatment naïve and interferon treatment experienced[20-24]. In this study, we present data from five National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) trials - SPARE[19] (using sofosbuvir and ribavirin), SYNERGY-A[18], and ERADICATE[25] (both using ledipasvir and sofosbuvir), and PIFNPK[26] and ALBIN[27] [studies of interferon (IFN)-ribavirin-based therapy among patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/HCV co-infection]. This study has two aims. Firstly, we address the impact of baseline MHD on SVR and adherence to sofosbuvir-based, interferon-free therapy. Secondly, we characterize the change in Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) scores among patients with HIV/HCV co-infection treated with sofosbuvir-based therapy and with interferon-based therapy. For our first aim we present data from three NIAID trials - SPARE[19] (using sofosbuvir and ribavirin), SYNERGY-A[18], and ERADICATE[25] (both using ledipasvir and sofosbuvir). For our second aim, BDI scores were obtained from patients enrolled in ERADICATE, PIFNPK and ALBIN.

Patients for all studies were enrolled from single center trials conducted at the Clinical Research Center of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States. Adult patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 (GT-1) infection naïve to HCV therapy were included. Written or oral informed consent approved by the NIAID Institutional Review Board was obtained from all patients. Full eligibility criteria for all 5 studies are as previously published[18,19,25-28].

SPARE was a 2-part, randomized controlled trial from October 2011 through April 2012[19]. Patients with early to moderate liver fibrosis were treated for 24 wk with 400 mg/d of sofosbuvir and weight-based ribavirin, 400 mg in the morning, 600 mg in the evening if < 75 kg or 600 mg twice a day if > 75 kg). A second cohort of patients with all stages of fibrosis (including compensated cirrhosis) was randomized to receive 400 mg/d of sofosbuvir in combination with either weight-based ribavirin or low-dose (600 mg/d) ribavirin for 24 wk[19].

SYNERGY-A was a phase 2a cohort study[18]. From January 2013 to December 2013, twenty GT-1 HCV-infected patients were treated for 12 wk with ledipasvir 90 mg and sofosbuvir 400 mg administered as a single combination pill (ledipasvir-sofosbuvir) taken once daily. Neither patient nor investigators were blinded[18].

ERADICATE was an open-label phase 2b trial of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir once daily to non-cirrhotic GT-1 HCV-infected patients with stable HIV-disease[25]. From June 2013 to February 2014, fifty HCV GT-1 patients were treated for 12 wk with ledipasvir and sofosbuvir.

In all three clinical trials of sofosbuvir-based therapy, patients with MHD were included. We retrospectively identified patients with baseline MHD defined as either: (1) a DSM IV diagnosis of major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, generalized anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder; or (2) requiring anti-depressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers or psychotropics prescribed by a psychiatrist.

SVR, defined as undetectable HCV RNA 12 wk post completion of treatment, was the primary outcome. Plasma HCV RNA levels were measured using the real time HCV assay (Abbott), with a lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of 12 IU/mL, and COBAS TaqMan HCV RNA assay version 2.0 (Roche), with an LLOQ of 43 IU/mL.

For all 3 studies, we performed pill counts at set time points: Sofosbuvir and ribavirin counts in SPARE; ledipasvir-sofosbuvir counts in SYNERGY-A and ERADICATE. Sofosbuvir adherence was documented during 11 time points based on participant recall and pill counts. Missed doses were recorded only through the time of treatment discontinuation in patients who stopped treatment early. We compared the percentage of patients who completed treatment with 3 or less missed pills to those who missed more than 3. For SYNERGY-A and ERADICATE, the average number of sofosbuvir-ledipasvir pills taken by patients in each group was also calculated.

In SPARE, attendance at study visits for all participants was monitored. In addition, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of sofosbuvir and its metabolite GS-331007 were obtained and calculated on 25 participants. Levels in serum were measured at 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36 h and at 14 d after administration of sofosbuvir and ribavirin using a high-performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry bioanalytical technique (QPS LLC) as previously described[19].

PIFNPK and ALBIN were open label, non-randomized studies designed to look at the safety, toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of interferon in combination with ribavirin. In the PIFNPK study, peginterferon alfa-2a 180 μg twice weekly (Pegasys; Roche Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA), was evaluated. In the ALBIN study, Alb-interferon (albumin/interferon alfa 2b fusion protein 900 μg subcutaneous injection every two weeks, Peg-Intron; Schering-Plough) was evaluated. Eligibility criteria as previously published[26-28].

BDI scores were collected prior to treatment (baseline), during treatment, and one to eight weeks post-end of treatment on participants with HIV/HCV co-infection from ERADICATE, PIFNPK, and ALBIN. BDI scores for all participants, and those who achieved SVR were evaluated.

Statistical differences in mean and observed frequencies for both aims were analyzed by Fisher’s Exact, and t-test with significance defined as a P value less than 0.05. Changes in observed frequencies in SVR and adherence between participants with MHD and those without for aim 1 were analyzed by Fisher’s Exact test within each study. Analyses were performed using PRISM 6.0 (GraphPad).

Baseline demographics: In all 3 studies, differences in baseline characteristics were not statistically significant between treatment groups (Table 1). The average age was 50-60 years, and participants were predominantly African American males with GT-1a genotype.

| SPARE (n = 23) | SYNERGY A (n = 7) | ERADICATE (n = 15) | P value | |

| Demographic | ||||

| Age, mean ± SD | 54 ± 6 | 52 ± 10 | 56 ± 8 | 0.44 |

| Male gender | 14 (61) | 5 (71) | 9 (60) | 0.86 |

| Race or ethnicity | 0.68 | |||

| White | 4 (17) | 2 (29) | 2 (13) | - |

| Black | 19 (83) | 5 (71) | 13 (87) | - |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| HCV genotype 1 subtype | 0.46 | |||

| 1A | 18 (78) | 4 (57) | 12 (80) | - |

| 1B | 5 (22) | 3 (43) | 3 (20) | - |

| HIV + | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 15 (100) | < 0.0001 |

| Mental health disorder | ||||

| Depression | 14 (61) | 4 (57) | 8 (53) | 0.89 |

| Anxiety | 4 (17) | 3 (43) | 1 (7) | 0.12 |

| Bipolar disorder | 4 (17) | 3 (43) | 5 (33) | 0.32 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 2 (7) | 1 (14) | 3 (20) | 0.60 |

| Schizophrenia | 0 | 1 (14) | 0 | - |

Mental health disease: Thirty-eight percent of participants in SPARE, 35% in SYNERGY-A, and 30% in ERADICATE were classified as having baseline MHD. The prevalence of disorders for each study is shown in Table 1. Depression was the most common disorder and many participants had more than one diagnosis.

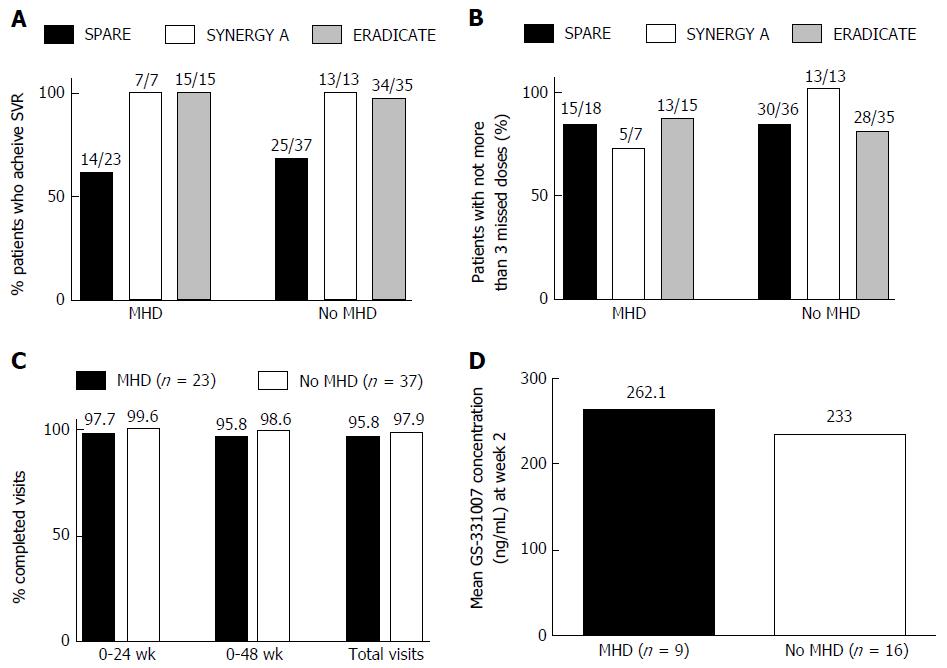

Treatment outcome: In all 3 studies the percentage of patients with MHD who achieved SVR was not statistically different from those without MHD (Figure 1A). In SPARE, 60.9% of those with MHD achieved SVR compared to 67.6% in those without (P = 0.78). In SYNERGY-A, 100% of both groups achieved SVR and in ERADICATE 100% of those with and 97.1% of those without MHD achieved SVR.

Patient adherence: (1) pill counts; in SYNERGY-A those with MHD and those without took, on average, 96.9% and 98.9% of their pills, respectively (P = 0.5). Both groups in ERADICATE took, on average, 97.8% of their pills. There was no statistically significant difference between groups with respect to the numbers that completed treatment with no more than 3 missed pills (Figure 1B): In SPARE, 83% in both groups completed treatment with no more than 3 missed pills. In SYNERGY-A, 5 of the 7 patients (71%) with MHD missed no more than 3 pills compared to 13 out of 13 (100%) among those without MHD (P = 0.11). In ERADICATE 13 out of 15 (87%) of those with MHD compared to 28 out of 35 (80%) of those without completed treatment with no more than 3 missed pills (P = 0.7); (2) adherence to study visit-SPARE; there was no difference in the proportion of patients with MHD and those without who completed the total required visits (95.8% vs 97.9%, P = 0.12) (Figure 1C); and (3) Serum levels of GS-331007-SPARE; We obtained pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic data for GS-331007 from 25 patients. Nine had MHD compared to 16 without. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean serum concentrations of GS-331007 for each group at week 2 of treatment (P = 0.72) (Figure 1D).

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the patients treated with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir and IFN-based therapy. Age and sex were similar in both groups; however, the ledipasvir-sofosbuvir-treatment group included more African-American and fewer patients with late stage 2-4 disease. While more participants had baseline MHD in the IFN-based treatment group, baseline BDI scores were similar among the patients of both treatment groups (ledipasvir-sofosbuvir 5.24 ± SD 5.48, IFN-based 6.96 ± SD 8.67; P = 0.14).

| Demographic | Sofosbuvir-based therapy (n = 50) | Interferon-based therapy (n = 26) | P value |

| Age, median | 58 | 47 | |

| Male | 37 (74) | 22 (84) | 0.79 |

| African American | 42 (84) | 11 (42) | 0.0004 |

| Fibrosis | 0.00132 | ||

| F0-1 | 35 (70) | 10 (38) | |

| F2-4 | 15 (30) | 16 (62) | |

| SVR | 49 (98) | 13 (50) | 0.0001 |

| Baseline mental health disease | 15 (30) | 15 (58) | 0.0264 |

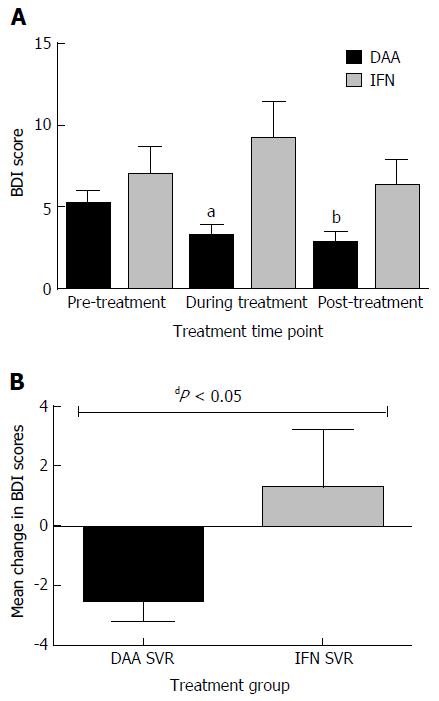

Patients treated with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir: Mean BDI scores decreased from 5.24 at baseline to 3.28 during treatment (1.96 decrease, ± SD 4.50, P = 0.0034) and 2.82 post-treatment. The decrease in mean score from baseline to post-treatment was also statistically significant (-2.42 ± SD 4.99, P = 0.0012, Figure 2A).

Patients treated with IFN: Mean BDI score increased from 6.96 at day zero to 9.19 during treatment. This change was not statistically significant (an increase of 2.46 ± SD 8.96; P = 0.1), and then decreased back to baseline post-treatment (mean BDI score 6.3 ± SD 7.91; P = 0.54, Figure 2A).

Comparison of change in BDI scores from baseline to during and post-treatment: The overall change in BDI scores from baseline to during treatment among patients treated with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir (-1.96 ± SD 4.5) compared to the change among those treated with IFN (+2.23 ± SD 7.5) was statistically significant (P = 0.0032, Figure 2A). However, change from baseline to post-treatment was not statistically significant (-2.42 ± SD 4.99 vs -0.65 ± SD 6.24; P = 0.18).

Patients treated with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir who achieved SVR: Forty-nine out of the 50 (98%) patients treated achieved SVR. Baseline BDI was 5.35 + SD 5.48. Mean BDI decreased to 3.35 ± SD 4.75 during treatment (an overall change of -2 ± SD 4.45, P = 0.0034), and further decreased to 2.88 ± SD 5 post-treatment. The change in mean BDI from baseline to post-treatment was statistically significant (-2.47 ± SD 5.03, P = 0.0012).

Patients treated with IFN and achieved SVR: Eleven out of 26 (42%) patients achieved SVR. Among these participants, mean baseline BDI was 4.55 ± SD 4.48. This increased to 8.91 ± SD 7.67 during treatment (P = 0.07) and then returned to baseline of 5.81 ± SD 6.4.

Mean BDI among participants treated with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir decreased 2 ± SD 4.54 from baseline to during-treatment, whereas among participants treated with IFN-based therapy, mean BDI increased by 4.36 ± SD 7.2. This difference in changes in mean BDI scores was statistically significant (P = 0.0004).

Similarly, the difference in change in mean BDI from baseline to post-treatment was also statistically significant (-2.47 ± SD 5.03, compared to +1.27 ± SD 6.36, P = 0.038).

Sofosbuvir-based therapy was equally effective among participants with MHD, and among those without MHD. Patients with baseline MHD demonstrated similar levels of adherence with study visits, study drugs, and achieved similar rates of SVR to those who did not have a baseline MHD diagnosis. Furthermore, among participants with HIV/HCV coinfection treated with DAA therapy, we observed a statistically significant improvement in BDI scores during and after the end of treatment time point (post-treatment) compared to baseline (pre-treatment), while participants treated with IFN-based therapy saw no significant change in BDI scores.

In a study of 4084 United States veterans, psychiatric disease was identified as a predictor of non-treatment (odds ratio = 9.45)[29]. Furthermore, due to shared transmission routes, HIV/HCV coinfection can be high among certain cohorts. A cross sectional study of a large cohort of patients with HIV found that 21% were coinfected with HCV. Among these patients with HIV/HCV coinfection, depression severity scores were higher, and antidepressant medications were more often prescribed, compared to patients with HIV mono-infection[30]. Concern for emergent or worsening of neuropsychiatric side effects associated with interferon-based HCV therapy resulted in treatment deferment even for patients with stable MHD[14,31,32]. The treatment of chronic HCV, however, has evolved to interferon-free, all-oral, DAA regimens. Concerns regarding adherence to and subsequent success with DAA regimens among patients with MHD remains to be addressed.

This study has 2 aims: Firstly, to address the impact of baseline MHD on adherence to and subsequent success with DAA regimens among patients with MHD; and secondly, to describe the change in BDI scores among patients treated with a sofosbuvir-based regimen (ledipasvir-sofosbuvir) and compare this to the change among patients treated with IFN-based therapy.

In the current study, we combined results from three studies using interferon-free regimens. We compared the effect of MHD on outcome (SVR) and three modalities of adherence (pill count, study visits and serum levels of GS-331007). The prevalence of MHD among the 3 studies (approximately 35%) was comparable to the baseline prevalence reported in other studies[7,10-14]. This study demonstrates that patients with MHD can achieve SVR at rates comparable to those without MHD. Six patients from SPARE did not complete treatment, 5 of which were identified as suffering from MHD but only one discontinuation from study could be attributed to MHD as determined by evaluation by the principal investigator. This suggests that these interferon-free regimens did not affect adherence and subsequent efficacy of therapy.

For our second aim, we analyzed baseline pre-treatment, during treatment, and post-treatment BDI scores among HIV/HCV coinfected participants treated with a sofosbuvir-based regimen (ledipasvir-sofosbuvir) in the ERADICATE study and coinfected participants treated with IFN-based therapy (PFINPK and ALBIN). Mean changes from baseline to during and to post-treatment were compared within, and between, each treatment group. We demonstrate that despite similar baseline BDI scores in both treatment groups, participants treated with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir saw a decrease in BDI scores during treatment and post-treatment compared to baseline. However, participants treated with IFN-based therapy did not see any change in BDI scores. In fact, when treatment groups were compared to each other and adjusted for participants who achieved SVR, the overall decrease in BDI score from baseline to post-treatment among participants treated with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir was significantly different compared to the overall increase in BDI score among participants treated with IFN-based therapy. It is conceivable that successful treatment of HCV alone should be associated with improvement in mental health. However, our findings suggest that sofosbuvir-based (and possibly any IFN-free) anti-HCV therapy may have additional mental health benefits beyond end of treatment.

This study is strengthened by multiple measures of adherence: Pill counts for all 3 studies; and in SPARE study visits with the additional objective measure of serum levels of the sofosbuvir metabolite GS-331007 at week 2 of therapy. Adherence to oral DAA therapy was high in all 3 studies, regardless of baseline MHD status, with no significant differences in pill counts, study visits, and serum GS-331007 levels between those with and without MHD. Whether the high adherence was a consequence of participant selection and the more intensive adherence interventions and counseling that are inherent to clinical trials, or related to the improved tolerability and ease of administration of the medications cannot be determined.

Limitations of this study include its small sample sizes for the three patient groups analyzed and therefore may not be sufficiently powered to detect differences. This did not allow for addressing the hypothesis that a regimen of fewer pills for shorter duration (1 pill once a day in ERADICATE and SYNERGY-A for 12 wk compared to several pills a day for 24 wk in SPARE) was associated with significantly higher adherence. Furthermore, combining more than one study did result in a non-homogenous study population, most evident in the difference in baseline fibrosis stage among the participants undergoing BDI evaluation. Finally, this study did not include patients with severe, uncontrolled MHD therefore may have been biased towards those who already had a background of good adherence or lower BDI scores.

We hope that these preliminary findings will open the dialogue to further expand eligibility to those with MHD and lead to further, larger studies involving patients with more challenging characteristics: Not just those with baseline MHD, but also those with substance abuse - two diagnoses which are frequently paired[5-8]. Inclusion of these marginalized groups will be necessary if we are to gain an advantage in the battle to eradicate hepatitis C.

In conclusion, our study supports that patients with baseline MHD can be successfully engaged and treated with DAA therapies, and that sofosbuvir-based therapy is associated with improvement in BDI scores.

The treatment of chronic hepatitis C has evolved from interferon-based to direct acting antiviral-based therapy, with high tolerability and efficacy. Much focus has now shifted to increasing access to these new agents. However, the prevalence of mental health disease (MHD) is high among patients with hepatitis C and MHD is one of the most frequently cited reasons for withholding hepatitis C therapy.

The author’s group focuses on hepatitis C eradication strategies among urban populations with unique patient populations that are predominantly African American, with advanced liver fibrosis, and high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus co-infection and MHD. The authors believe that patients with MHD can be safely and effectively treated for hepatitis C with direct acting antiviral therapy. The findings of this study supports this hypothesis.

Patients with mental health diseases may be excluded from hepatitis C therapy due to concerns for exacerbation of psychiatric complications, adherence, concurrent substance abuse, and reinfection due to continued high-risk behaviors. Hepatitis C therapy has evolved from interferon-based to direct acting antiviral agents, which are associated with minimal side effects. However, the high cost of these agents has led to restricted access to these medications. This study addresses the concerns regarding adherence to and subsequent success with directly acting antiviral regimens among patients with MHD. Furthermore, the findings of this study suggest that sofosbuvir-based therapy may be associated with improvements in Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) scores.

The findings of this study supports policy change to increase eligibility and access to hepatitis C therapy with new direct acting antiviral therapies among patients with mental health disease.

Sofosbuvir is a direct acting antiviral nucleotide inhibitor that acts upon the hepatitis C NS5B polymerase, preventing viral replication, and is the backbone to several hepatitis C treatment regimens. BDI is a multiple-choice tool for measuring the severity of depression.

Study of mental health in hepatitis C virus treated patients is considered to be a good practical point.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Olmo D, Marchan-Lopez A, Shiha G S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57:1333-1342. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1770] [Cited by in RCA: 1840] [Article Influence: 153.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:705-714. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1484] [Cited by in RCA: 1461] [Article Influence: 76.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim WR. The burden of hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology. 2002;36:S30-S34. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Davis GL, Alter MJ, El-Serag H, Poynard T, Jennings LW. Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:513-521, 521.e1-e6. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 671] [Cited by in RCA: 662] [Article Influence: 44.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Loftis JM, Matthews AM, Hauser P. Psychiatric and substance use disorders in individuals with hepatitis C: epidemiology and management. Drugs. 2006;66:155-174. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fireman M, Indest DW, Blackwell A, Whitehead AJ, Hauser P. Addressing tri-morbidity (hepatitis C, psychiatric disorders, and substance use): the importance of routine mental health screening as a component of a comanagement model of care. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40 Suppl 5:S286-S291. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | el-Serag HB, Kunik M, Richardson P, Rabeneck L. Psychiatric disorders among veterans with hepatitis C infection. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:476-482. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sockalingam S, Blank D, Banga CA, Mason K, Dodd Z, Powis J. A novel program for treating patients with trimorbidity: hepatitis C, serious mental illness, and active substance use. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:1377-1384. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, Swartz MS, Essock SM, Butterfield MI, Constantine NT, Wolford GL, Salyers MP. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:31-37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tavakkoli M, Ferrando SJ, Rabkin J, Marks K, Talal AH. Depression and fatigue in chronic hepatitis C patients with and without HIV co-infection. Psychosomatics. 2013;54:466-471. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Falck-Ytter Y, Kale H, Mullen KD, Sarbah SA, Sorescu L, McCullough AJ. Surprisingly small effect of antiviral treatment in patients with hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:288-292. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yovtcheva SP, Rifai MA, Moles JK, Van der Linden BJ. Psychiatric comorbidity among hepatitis C-positive patients. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:411-415. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rowan PJ, Tabasi S, Abdul-Latif M, Kunik ME, El-Serag HB. Psychosocial factors are the most common contraindications for antiviral therapy at initial evaluation in veterans with chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:530-534. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu JY, Shadbolt B, Teoh N, Blunn A, To C, Rodriguez-Morales I, Chitturi S, Kaye G, Rodrigo K, Farrell G. Influence of psychiatric diagnosis on treatment uptake and interferon side effects in patients with hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1258-1264. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sherman KE, Flamm SL, Afdhal NH, Nelson DR, Sulkowski MS, Everson GT, Fried MW, Adler M, Reesink HW, Martin M. Response-guided telaprevir combination treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1014-1024. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 592] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 42.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kwo PY, Lawitz EJ, McCone J, Schiff ER, Vierling JM, Pound D, Davis MN, Galati JS, Gordon SC, Ravendhran N. Efficacy of boceprevir, an NS3 protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C infection (SPRINT-1): an open-label, randomised, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:705-716. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 567] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kelly EM, Corace K, Emery J, Cooper CL. Bipolar patients can safely and successfully receive interferon-based hepatitis C antiviral treatment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:811-816. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kohli A, Osinusi A, Sims Z, Nelson A, Meissner EG, Barrett LL, Bon D, Marti MM, Silk R, Kotb C. Virological response after 6 week triple-drug regimens for hepatitis C: a proof-of-concept phase 2A cohort study. Lancet. 2015;385:1107-1113. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Osinusi A, Meissner EG, Lee YJ, Bon D, Heytens L, Nelson A, Sneller M, Kohli A, Barrett L, Proschan M. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for hepatitis C genotype 1 in patients with unfavorable treatment characteristics: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:804-811. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, Chojkier M, Gitlin N, Puoti M, Romero-Gomez M, Zarski JP, Agarwal K, Buggisch P. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1889-1898. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1357] [Cited by in RCA: 1361] [Article Influence: 123.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, Hyland RH, Ding X, Mo H, Symonds WT, McHutchison JG, Membreno FE. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:515-523. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 429] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lawitz E, Sulkowski MS, Ghalib R, Rodriguez-Torres M, Younossi ZM, Corregidor A, DeJesus E, Pearlman B, Rabinovitz M, Gitlin N. Simeprevir plus sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, to treat chronic infection with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 in non-responders to pegylated interferon and ribavirin and treatment-naive patients: the COSMOS randomised study. Lancet. 2014;384:1756-1765. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 602] [Cited by in RCA: 595] [Article Influence: 54.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sulkowski MS, Gardiner DF, Rodriguez-Torres M, Reddy KR, Hassanein T, Jacobson I, Lawitz E, Lok AS, Hinestrosa F, Thuluvath PJ. Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for previously treated or untreated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:211-221. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 933] [Cited by in RCA: 889] [Article Influence: 80.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, Lawitz E, Gordon SC, Schiff E, Nahass R, Ghalib R, Gitlin N, Herring R. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1483-1493. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1065] [Cited by in RCA: 1060] [Article Influence: 96.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Osinusi A, Townsend K, Kohli A, Nelson A, Seamon C, Meissner EG, Bon D, Silk R, Gross C, Price A. Virologic response following combined ledipasvir and sofosbuvir administration in patients with HCV genotype 1 and HIV co-infection. JAMA. 2015;313:1232-1239. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Murphy AA, Herrmann E, Osinusi AO, Wu L, Sachau W, Lempicki RA, Yang J, Chung TL, Wood BJ, Haagmans BL. Twice-weekly pegylated interferon-α-2a and ribavirin results in superior viral kinetics in HIV/hepatitis C virus co-infected patients compared to standard therapy. AIDS. 2011;25:1179-1187. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Osinusi A, Bon D, Nelson A, Lee YJ, Poonia S, Shivakumar B, Cai SY, Wood B, Haagmans B, Lempicki R. Comparative efficacy, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic activity, and interferon stimulated gene expression of different interferon formulations in HIV/HCV genotype-1 infected patients. J Med Virol. 2014;86:177-185. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Osinusi A, Rasimas JJ, Bishop R, Proschan M, McLaughlin M, Murphy A, Cortez KJ, Polis MA, Masur H, Rosenstein D. HIV/Hepatitis C virus-coinfected virologic responders to pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy more frequently incur interferon-related adverse events than nonresponders do. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:357-363. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bini EJ, Bräu N, Currie S, Shen H, Anand BS, Hu KQ, Jeffers L, Ho SB, Johnson D, Schmidt WN. Prospective multicenter study of eligibility for antiviral therapy among 4,084 U.S. veterans with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1772-1779. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yoon JC, Crane PK, Ciechanowski PS, Harrington RD, Kitahata MM, Crane HM. Somatic symptoms and the association between hepatitis C infection and depression in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Care. 2011;23:1208-1218. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lim C, Olson J, Zaman A, Phelps J, Ingram KD. Prevalence and impact of manic traits in depressed patients initiating interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e141-e146. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Alavi M, Grebely J, Matthews GV, Petoumenos K, Yeung B, Day C, Lloyd AR, Van Beek I, Kaldor JM, Hellard M. Effect of pegylated interferon-α-2a treatment on mental health during recent hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:957-965. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |