Published online Sep 27, 2023. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v15.i9.1033

Peer-review started: May 7, 2023

First decision: June 7, 2023

Revised: July 7, 2023

Accepted: August 25, 2023

Article in press: August 25, 2023

Published online: September 27, 2023

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) manifests within a broad ethnic and racial spectrum, reflecting different levels of access to health care.

To evaluate the clinical profile, complications and survival rates of patients with PSC undergoing liver transplantation (LTx) at a Brazilian reference center.

All patients diagnosed with PSC before or after LTx were included. The medical records were reviewed for demographic and clinical variables, including outcomes and survival. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

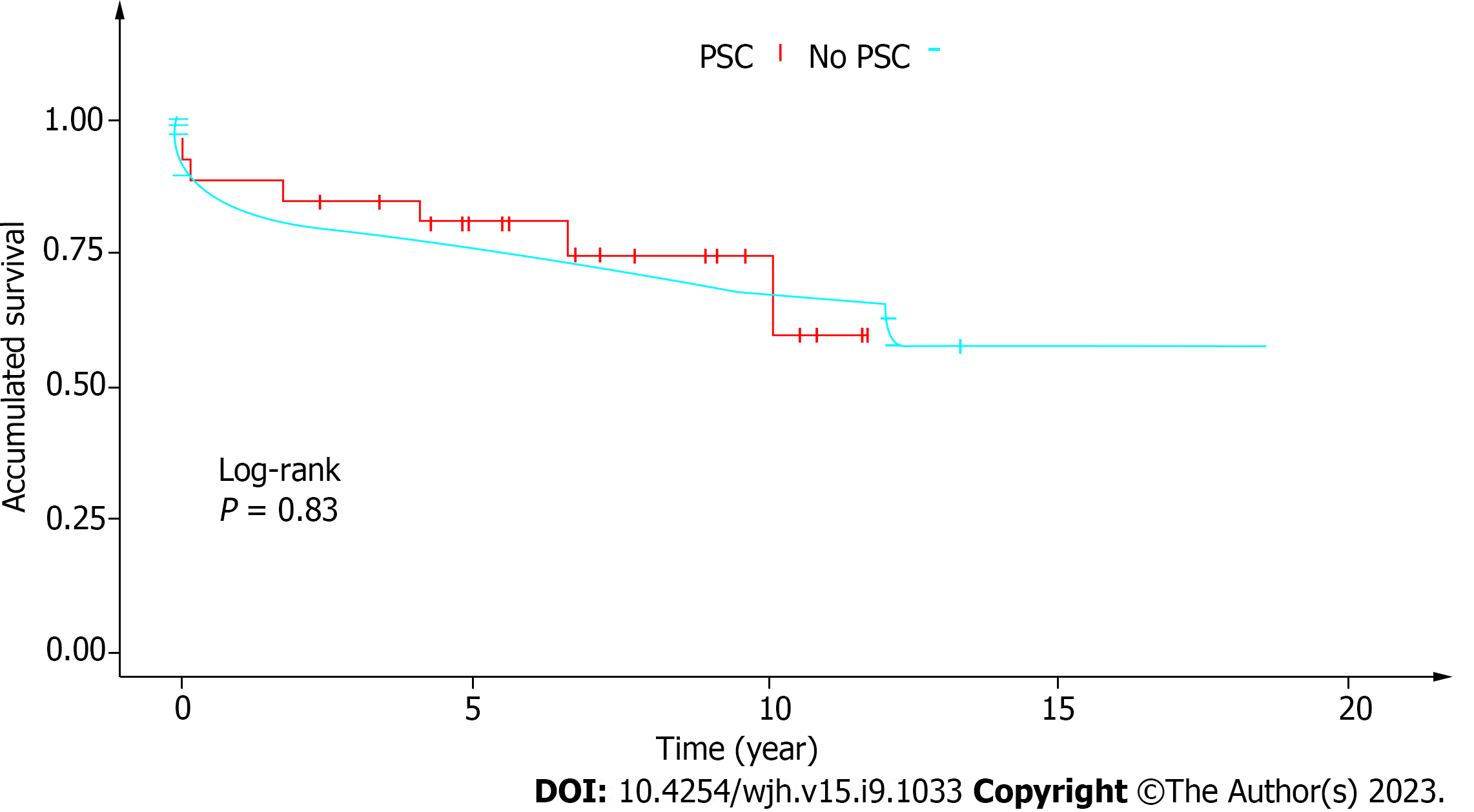

Our cohort represented 1.6% (n = 34) of the 2113 patients receiving liver grafts at our service over the past two decades. Most were male (n = 19; 56%). The average age (40 ± 14 years) was similar for men and women (P = 0.347). The mean follow-up time from diagnosis to LTx was 68 mo. Most patients had the classic form of PSC. Three women had PSC/autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome, and one patient had small-duct PSC. Alkaline phosphatase levels at diagnosis and pre-LTx model for end-stage liver disease. scores were significantly higher in males. Inflammatory bowel research (IBD) was investigated by colonoscopy in 26/34 (76%) and was present in most cases (18/26; 69%). IBD was less common in women than in men (44.4% vs. 55.6%) (P = 0.692). Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) was diagnosed in 2/34 (5.9%) patients by histopathology of the explant (survival: 3 years 6 mo, and 4 years 11 mo). Two patients had complications requiring a second LTx (one after 7 d due to hepatic artery thrombosis and one after 17 d due to primary graft dysfunction). Five patients (14.7%) developed biliary stricture. The overall median post-LTx survival was 66 mo. Most deaths occurred in the first year (infection n = 2, primary liver graft dysfunction n = 3, unknown cause n = 1). The 1-year and 5-year survival rates of this cohort were 82.3% and 70.6%, respectively, matching the mean overall survival rates of LTx patients at our center (87.1% and 69.43%, respectively) (P = 0.83).

Survival after 1 and 5 years was similar to that of other LTx indications. The observed CCA survival rate suggests CCA may be an indication for LTx in selected cases.

Core Tip: We present a case series of liver transplantation (LTx) patients from the largest center in Northeastern Brazil, with epidemiological features different from what is expected for primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) (e.g., early manifestation and proportion of female patients). The finding of two cases of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) with good survival is relevant to the discussion on the eligibility of selected cases of CCA for LTx. The survival of PSC patients was similar to that of LTx patients with other etiologies.

- Citation: Freitas LTS, Hyppolito EB, Barreto VL, Júnior LHJC, Jorge BCM, Háteras FCTSB, Marzola MB, Lima CA, Celedonio RM, Coelho GR, Garcia JHP. Liver transplant in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: A retrospective cohort from Northeastern Brazil. World J Hepatol 2023; 15(9): 1033-1042

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v15/i9/1033.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v15.i9.1033

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic, progressive autoimmune disease causing inflation, stenosis and dilation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts[1]. Clinically characterized mainly by fatigue and pruritus[2], PSC may lead to cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) and cirrhosis. Around 70% of PSC patients have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), especially ulcerative colitis, with elevated risk of colorectal cancer[3]. Currently available clinical treatments do not alter the natural history of PSC, and liver transplantation (LTx) is the only curative treatment available[4], although some studies have reported a post-LTx relapse rate of as much as 25%[5]. Intractable pruritus, recurrent cholangitis, hepatocarcinoma and decompensated cirrhosis are some of the classic indications for LTx[1], but the ideal moment for transplantation can be difficult to determine. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical profile, complications and survival rates of PSC patients submitted to LTx at a Brazilian referral center.

In this retrospective observational cohort study, we included all LTx patients diagnosed with PSC before or after transplantation. The diagnosis was based on clinical and laboratory findings confirmed by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Between May 2012 and May 2022, the LTx team at our service (Hospital Universitário Walter Cantídio, Federal University of Ceará, partnered with Hospital São Carlos) performed 2113 procedures; 34 of which (1.6%) were due to PSC. The study variables were age, sex, clinical manifestations, association with IBD and other comorbidities, time between diagnosis of PSC and LTx, cause of LTx, PSC classification, laboratory findings, treatments and complications prior to LTx, time of ischemia, Child–Pugh and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores, immunosuppression, PSC relapse following LTx, rejection, and death.

Histopathological diagnosis of small-duct PSC was considered when liver biopsy was performed prior to LTx or in the explant biopsy. Small-duct PSC was defined as cholestasis associated with a compatible liver biopsy, in the absence of biliary stricture on ERCP or MRCP. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) was diagnosed using the International AIH Group Score[6].

PSC relapse was defined as the presence on ERCP or MRCP of biliary stricture post-LTx at a site other than the anastomosis. The follow-up time was defined as the time of outpatient follow-up until the moment of inclusion in the study, or death.

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Ceará and filed under #CAAE 98627218.6.2018.5045.

The level of statistical significance was set at 5% (P < 0.05). Non-normally distributed data were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test, while the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables. Cumulative survival rates at the 95% confidence interval were estimated with Kaplan–Meier survival analysis.

Male sex was slightly predominant (n = 19; 56%). The average age was 40 ± 14 years, with no significant difference between men (38 ± 14 years) and women (43 ± 13 years) (P = 0.347). The mean MELD score was 24.1 ± 4.7 for men and 19.9 ± 8.1 for women (P = 0.011). The average time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 23 mo (range: 0–128 mo). The mean follow-up time from diagnosis to LTx was 68 mo (range: 0–196 mo). Classic PSC was the most frequently observed clinical form. Three women had AIH–PSC overlap syndrome, and one patient had small-duct PSC. All patients were symptomatic at diagnosis (Table 1).

| Variables | n | Total1 | Females (n = 141) | Males (n = 191) | P value2 |

| Age at LTx, yr | 32 | 40 ± 14 (36) | 43 ± 13 (39) | 38 ± 14 (35) | 0.347 |

| Age at first symptom, yr | 30 | 32 ± 14 (30) | 35 ± 13 (36) | 30 ± 14 (29) | 0.498 |

| Age at IBD diagnosis, yr | 17 | 35 ± 14 (32) | 37 ± 18 (42) | 33 ± 12 (30) | 0.370 |

| Months between 1st symptom and 1st consultation | 26 | 18 ± 37 (2) | 16 ± 33 (3) | 19 ± 39 (2) | 0.616 |

| Months between onset of symptoms and diagnosis | 31 | 80 ± 235 (23) | 148 ± 357 (56) | 31 ± 41 (13) | 0.155 |

| Baseline clinical symptoms | |||||

| Jaundice | 32 | 29 (91%) | 11 (85%) | 18 (95%) | 0.552 |

| Pruritus | 32 | 25 (74%) | 6 (24%) | 19 (76%) | |

| Fever + shivering | 32 | 14 (44%) | 5 (38%) | 9 (47%) | 0.618 |

| Weight loss | 32 | 18 (56%) | 9 (69%) | 9 (47%) | 0.221 |

| Fatigue | 32 | 13 (41%) | 6 (46%) | 7 (37%) | 0.598 |

| PSC classification | |||||

| Classic PSC | 31 | 30 (97%) | 12 (92%) | 18 (100%) | 0.419 |

| PSC + AIH | 31 | 3 (9.7%) | 3 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 0.064 |

| Small-duct PSC | 31 | 1 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.6%) | > 0.999 |

| Diagnostic testing | |||||

| MRCP realized | 32 | 23 (72%) | 10 (77%) | 13 (68%) | 0.704 |

| MRCP | 32 | 20 (62%) | 10 (77%) | 10 (53%) | 0.163 |

| ERPC | 32 | 12 (38%) | 3 (23%) | 9 (47%) | 0.163 |

| Biopsy | 31 | 20 (65%) | 7 (54%) | 13 (72%) | 0.449 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes | 32 | 7 (22%) | 2 (15%) | 5 (26%) | 0.671 |

| Hypertension | 32 | 6 (19%) | 4 (31%) | 2 (11%) | 0.194 |

| Dyslipidemia | 32 | 4 (12%) | 2 (15%) | 2 (11%) | > 0.999 |

| Obesity | 32 | 1 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.3%) | > 0.999 |

| Smoking | 32 | 4 (12%) | 2 (15%) | 2 (11%) | > 0.999 |

| Drinking | 32 | 6 (19%) | 2 (15%) | 4 (21%) | > 0.999 |

| Others | 31 | 8 (26%) | 2 (17%) | 6 (32%) | 0.433 |

| IBD | 18 | > 0.999 | |||

| Ulcerative rectocolitis | 15 (83%) | 7 (88%) | 8 (80%) | ||

| Crohn’s disease | 3 (17%) | 1 (12%) | 2 (20%) | ||

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 32 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Seronegative arthritis | 32 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Gallbladder calculus | 32 | 7 (22%) | 3 (23%) | 4 (21%) | > 0.999 |

| Gallbladder polyps | 31 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Neoplasia | 31 | 4 (13%) | 2 (15%) | 2 (11%) | > 0.999 |

| Dyslipidemia | 32 | 4 (12%) | 2 (15%) | 2 (11%) | > 0.999 |

| Obesity | 32 | 1 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.3%) | > 0.999 |

| Smoking | 32 | 4 (12%) | 2 (15%) | 2 (11%) | > 0.999 |

| Drinking | 32 | 6 (19%) | 2 (15%) | 4 (21%) | > 0.999 |

| Other | 31 | 8 (26%) | 2 (17%) | 6 (32%) | 0.433 |

| Treatment | |||||

| Ursodeoxycholic acid | 29 | 27 (93%) | 11 (92%) | 16 (94%) | 0.665 |

| Prednisone | 27 | 14 (52%) | 9 (75%) | 5 (33%) | 0.031 |

| Endoscopic treatment | 16 | 8 (50%) | 1 (12%) | 7 (88%) | 0.010 |

| Indication for LTx | > 0.999 | ||||

| Untreatable pruritus | 4 (12%) | 2 (15%) | 2 (11%) | ||

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 27 (84%) | 11 (85%) | 16 (84%) | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.3%) | ||

| Dominant stenosis | 26 | 4 (15%) | 1 (9.1%) | 3 (20%) | 0.614 |

Nearly all patients (n = 27; 93%) were treated with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) and half (n = 14; 52%) used prednisone. All users of prednisone had overlap with AIH, with a predominance of the female sex (75%; P = 0.031). Endoscopic treatment was administered significantly more often to men (88%) than to women (12%) (P = 0.010). Alkaline phosphatase levels at diagnosis and pre-LTx MELD scores were significantly higher in males. The baseline and pre-LTx laboratory findings are shown in Table 2.

| Variables | n | Total1 | Females (n = 141) | Males (n = 191) | P value2 |

| ALP/RV1c | 19 | 3.72 ± 3.02 (2.86) | 2.23 ± 1.58 (1.89) | 4.60 ± 3.37 (3.35) | 0.045 |

| GGT/RV1c | 19 | 10 ± 9 (5) | 5 ± 4 (4) | 12 ± 9 (10) | 0.210 |

| AST/RV1c | 23 | 5.86 ± 11.29 (3.00) | 10.63 ± 18.86 (3.30) | 3.31 ± 1.53 (2.86) | 0.591 |

| ALT/RV1c | 23 | 3.28 ± 3.19 (2.46) | 3.80 ± 5.18 (1.93) | 3.01 ± 1.53 (2.75) | 0.302 |

| DB | 24 | 7.4 ± 5.3 (5.9) | 8.9 ± 5.2 (7.3) | 6.8 ± 5.4 (5.9) | 0.383 |

| Antibody testing | |||||

| ANA | 20 | 3 (15%) | 1 (17%) | 2 (14%) | > 0.999 |

| AASM | 19 | 2 (11%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (7.7%) | > 0.999 |

| AMA | 19 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| ANTI-SLA | 11 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| pANCA | 12 | 4 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 3 (33%) | > 0.999 |

| Pre-LTx lab results | |||||

| ALT/RV | 22 | 5.5 ± 8.8 (3.0) | 6.2 ± 12.6 (2.1) | 4.9 ± 4.1 (4.0) | 0.138 |

| AST/RV | 23 | 16 ± 44 (5) | 24 ± 66 | 9 ± 14 (5) | 0.107 |

| ALP/RV | 22 | 2.79 ± 2.24 (1.84) | 2.39 ± 2.37 (1.64) | 3.06 ± 2.20 (2.54) | 0.393 |

| TB | 22 | 15 ± 10 (11) | 13 ± 10 (10) | 17 ± 10 (12) | 0.324 |

| INR | 27 | 2.08 ± 2.34 (1.51) | 1.40 ± 0.32 (1.37) | 2.54 ± 2.98 (1.71) | 0.025 |

| Creatinine | 28 | 0.89 ± 0.80 (0.75) | 0.94 ± 1.19 (0.52) | 0.86 ± 0.34 (0.83) | 0.143 |

| MELD | 27 | 22.4 ± 6.5 (22.0) | 19.9 ± 8.1 (19.0) | 24.1 ± 4.7 (23.5) | 0.011 |

IBD was investigated by colonoscopy in 26 (76%) of 34 patients, and was present in most cases (18/26; 69%). The development of IBD was less common in women (44.4%) than in men (55.6%) (P = 0.692).

The mean age of PSC patients at the time of IBD diagnosis was 35 ± 14 years (median: 32 years). PSC and IBD were diagnosed simultaneously in two (11%) patients. PSC was diagnosed before IBD (range: 1–6.8 years; median: 3 years) in 6/18 (33%), and after IBD (range: 0.5–32 years; median 9.8 years) in 10/18 (56%). Patients without IBD (MELD: 24.6 ± 5.3) were significantly more severe at the time of LTx than patients with some form of IBD (19.3 ± 4.7) (P = 0.033). Table 3 shows the patients’ clinical variables according to the presence/absence of IBD.

| Total1 | IBD1 yes | IBD1 no | P value2 | |

| Total | 26 | 18 (69.2%) | 9 (30.8%) | 0.440 |

| Sex | 0.692 | |||

| Male | 16 (59%) | 6 (67%) | 10 (56%) | |

| Female | 11 (41%) | 3 (33%) | 8 (44%) | |

| Age | 40 ± 13 (36) | 38 ± 15 (34) | 35 ± 14 (32) | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 15 (83%) | |||

| Crohn’s disease | 3 (17%) | |||

| AST/RV1c | 6.1 ± 12.1 (2.9) | 12.2 ± 19.8 (3.7) | 2.8 ± 1.6 (2.6) | 0.014 |

| DM | 5 (19%) | 4 (44%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0.030 |

| Esophageal varices | 0.027 | |||

| No | 9 (36%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (50%) | |

| Yes | 16 (64%) | 7 (100%) | 9 (50%) | |

| MELD | 21.3 ± 5.5 (22.0) | 24.6 ± 5.4 (23.0) | 19.3 ± 4.7 (19.0) | 0.033 |

| Anastomosis | ||||

| Roux-en-Y | 8 (31%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (47%) | 0.023 |

| End-to-end | 18 (69%) | 9 (100%) | 9 (53%) |

Diabetes mellitus (DM) was the most frequent comorbidity (n = 7; 22%), followed by systemic arterial hypertension and alcoholism (n = 6; 19%), dyslipidemia and smoking (n = 4; 12%), obesity (n = 1; 3.1%) and others (n = 3; 9%). DM was more frequent in patients without IBD (n = 4; 80%) than in patients with IBD (n = 1; 20%) (P = 0.030). Although frequently associated with PSC, ankylosing spondylitis and seronegative arthritis were not observed in this series. Information on densitometry was available for only four (12.5%) patients, although seven (21%) patients were undergoing treatment for osteoporosis.

Two techniques were used for bile duct reconstruction: end-to-end anastomosis (65%) and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (35%). The former was preferred in patients with macroscopically normal common bile ducts.

CCA was diagnosed in two (5.9%) of 34 patients upon the histopathological examination of the explant, with the following characteristics.

Case 1: 47-year old man. Explant with nodule measuring 3.0 cm 2.5 cm 2.5 cm, with periductal and neural involvement, involvement of the liver hilum and intrahepatic bile ducts, vascular invasion and compromised margins (pT2bN2). The patient was peremptorily treated with capecitabine for 6 mo after LTx, but after 2 years and 4 mo experienced a recurrence of the neoplasm in the inferior vena cava, pancreas and lung. At this point, immunosuppression was reduced and 10 sessions of systemic chemotherapy with gemcitabine/cisplatin were administered but without response. Following that, the liver hilum and chest were submitted to radiotherapy. After 3 years and 6 mo, the patient presented neoplastic obstruction of the biliary tract for which a metallic prosthesis was inserted. The patient continues to use oral capecitabine and presents an excellent overall condition and quality of life, despite the relapse, with a survival of 4 years and 11 mo.

Case 2: 40-year old man. Intraoperative diagnosis of nodule, later confirmed in the explant to be an adenocarcinoma with biliary pattern measuring 2.8 cm 2.5 cm, with infiltration of the liver parenchyma, lymphovascular and perineural invasion, and compromised margins (pT2bN2). After 1 year, the patient experienced a recurrence of the neoplasm in the hepatic artery and lung. Chemotherapy with capecitabine for 6 mo and local radiotherapy were administered. The patient developed biliary obstruction for which a metallic prosthesis was inserted. Currently, the patient is clinically well, with a survival of 3 years and 10 mo.

As for complications of LTx, two patients required a second transplant, one after 7 d due to hepatic artery thrombosis and one after 17 d due to primary graft dysfunction. Five (14.7%) patients developed biliary stricture (end-to-end, n = 3; Roux-en-Y, n = 2), treated with ERCP and percutaneous drainage, respectively. Two patients had post-LTx relapse of PSC, with the appearance of intrahepatic biliary stricture confirmed on MRCP at 11 years and 7 mo (survival: 14 years and 2 mo) and at 12 years and 6 mo (survival: 18 years).

The overall median post-LTx survival was 66 mo (range: 0–234 mo), with no significant difference between the sexes (

The 1-year and 5-year survival rates of our cohort were 82.3% and 70.6%, respectively. This is compatible with the average overall survival rates of LTx patients at our institution (87.1% and 69.43% respectively) (P = 0.83) (Figure 1).

PSC represented only 1.6% of all LTx patients in our study, compared with, for example, 15.3% in Nordic countries[6]. The balanced sex distribution in our cohort also differed from that in the international literature, which shows a male predominance (up to 2:1)[7], while matching the proportion observed in a Brazilian multicenter study, in which 45% of the patients were female[8].

The prevalence of classic PSC in our Brazilian cohort matched that of studies from Europe, North America and Australia[9]. The average age of our patients at diagnosis (33 years; range 11–61 years) was similar to that of a Latin American study (29 years; range 19–40 years), but lower than that of a British study (54 years; range 6–93 years)[3,8]. The mean time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis of PSC was almost twice as long as that in a Swedish study (16 mo)[10].

Elevated serum alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transferase levels are typical fin PSC patients, but we also observed aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels on average five and three times above the normal range at the time of diagnosis[11]. According to Williamson and Chapman[12], serum bilirubin levels tend to be normal at disease onset and occasionally fluctuate during the course of the disease. In our cohort, the median bilirubin level was 8.72 mg/dL.

PSC is often associated with IBD[7,13]. PSC may manifest before, concomitantly with, or after the diagnosis of IBD[11]. IBD was observed in 76% of our patients; 67% of whom had concomitant PSC and IDB. The proportion of patients diagnosed with IBD before PSC was similar to that of other studies, as was the predominance of ulcerative rectocolitis[3]. In our cohort, biochemical changes were more pronounced in patients without IBD than in patients with IBD, as was liver disease severity, the occurrence of esophageal varices, and the prevalence of DM, possibly due to the concomitant use of corticoids to treat IBD.

Current evidence suggests PSC–IBD may be a condition altogether different from PSC alone, and some have argued that PSC may have a protective effect on the course of IBD[12,14], considering the invariably benign course of IBD, with mild or no clinical symptoms and possibly even normal endoscopic appearance observed in PSC patients with a subdiagnosis of IBD. However, concomitant ulcerative rectocolitis increases the risk of colorectal cancer[15].

The presence of a range of autoantibodies in the serum of PSC patients suggests autoimmunity plays a role in pathogenesis, but diagnostic testing for autoantibodies is of limited use due to low sensitivity and specificity[16]. A review on PSC found a high prevalence of p-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (50%–80%), anti-nuclear antibody (7%–77%) and anti-mitochondrial autoantibodies (13%–20%)[17], but in our cohort, few patients were tested for antibodies and the prevalence was low.

Most of our patients (93%) were treated with UDCA at least until the time of LTx. UDCA is hepatoprotective in chronic cholestatic liver disease, but its efficacy in PSC has been questioned[18]. In a European study on treatment for PSC[19], 50% of physicians routinely prescribed UDCA for all patients, while 12% never prescribed it. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the British Society of Gastroenterology do not encourage the use of UDCA in PSC patients[20,21]. The 2009 guidelines of the European Association for the Study of the Liver state that “UDCA (15-20 mg/d) improves serum liver tests and surrogate markers of prognosis (I/B1), but does not reveal a proven benefit on survival (III/C2)”[22].

Lindor et al[23] (2009) conducted a double-blind randomized controlled trial on 150 adult PSC patients to evaluate prolonged use of high doses of UDCA (28–30 mg/kg/d). Liver tests did improve, but patients taking UDCA were at higher risk of severe adverse events and clinical outcomes such as cirrhosis, LTx, esophageal varices, CCA and death, when compared with patients receiving placebo. The drug is believed to modify the composition of the bile acids.

Wunsch et al[18] (2014) prospectively evaluated the withdrawal of UDCA over 3 mo in 26 PSC patients and found a significant increase in biochemical parameters, nonsignificant deterioration of quality of life in certain domains, and improvement of well-being in the social functioning domain and the mental component summary in SF-36.

Just over half the patients (52%) used prednisone. Immunosuppressants are rarely prescribed for PSC patients and are only indicated in cases of overlap[24].

According to Carey et al[4] (2015), up to one fourth of PSC patients submitted to LTx may experience recurrence. In this study, the only patient (3%) with recurrence had concomitant IBD. The association between PSC and IBD is well documented and may affect two thirds of PSC patients, especially when IBD is combined with ulcerative pancolitis[25].

According to Lopens et al[24] (2020), patients with concomitant PSC and IBD are at increased risk of liver disease, and the absence of IBD tends to improve the prognosis of PSC and lessen the risk of complications. In contrast, in our study, patients without IBD were not only significantly more severe at the time of LTx but also displayed greater biochemical changes in the early stages of the disease, when compared with patients with concomitant PSC and IBD.

In a large study from the Netherlands involving 3020 PSC patients, the mean time between diagnosis of PSC and indication for LTx was 27 years, compared to 9.7 years in our study[26].

A wide-ranging review by Song et al[27] has shown that the risk of CCA is 10 to 1000 times higher in patients with PSC than in the general population. The early diagnosis of CCA in two of our patients agrees with the literature, according to which CCA develops one year after LTx in 50% of cases[27].

In an epidemiological populational study evaluating the risk and malignancy of PSC in 590 patients, the time between diagnosis of PSC and the diagnosis of CCA was on average 6 years, and only 12% were diagnosed with PSC and CCA at the initial presentation. CCA was diagnosed in the first year in 15%, between the first and the tenth year in 37%, and > 10 years later in 37%. The cumulative risk of CCA after 10, 20 and 30 years was 6%, 14% and 20%, respectively[26].

CCA is a formal contraindication for LTx in Brazil. In our cohort, the rate of survival after early recurrence (2 patients) was better than the mean rate given in the literature, according to which the overall survival rate of intrahepatic CCA is 40.8% (39.8%–41.9%) at 1 year, and 9.8% (9%–10.5%) at 5 years[28]. Our 5-year post-LTx survival rate was higher than that of a British study (75%)[3].

Some caveats apply to this retrospective study: (1) The medical records displayed differences in completeness; (2) PSC and IBD may have been under-reported; and (3) some laboratory findings were inadequately recorded in the database. To obtain the most reliable data possible, primary information was collected from the initial physical, laboratory and image records through active search, while incomplete information and doubts arising from the medical records were addressed by directly contacting the patients by phone.

PSC is a rare cause of LTx in our service. In our cohort, the proportion of women was larger than expected. Survival at 1 and 5 years was satisfactory and similar to other LTx indications. CCA findings in explants with good survival rates raise the hypothesis that CCA may be an acceptable indication for LTx in selected cases.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare indication for liver transplantation (LTx). Male sex is predominant in European studies. The ideal moment for LTx can be difficult to determine. PSC is often associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and may recur after LTx.

A Brazilian multicenter study on PSC showed that LTx patient data are limited and little explored in research. Our LTx service is the largest in North/Northeastern Brazil, with an average of 150 procedures a year, indicating a potential for research. The diagnosis of IBD in PSC patients before and after LTx is often inadequate and requires more attention on part of LTx teams. The finding of associated cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) in explants, associated with good survival, was an additional motivating factor.

To evaluate the clinical profile, complications and survival rates of PSC patients submitted to LTx at a Brazilian referral center.

Retrospective study of medical records supplemented by telephone interviews with patients. The study contributed to setting up a database of PSC patients submitted to LTx at our service.

PSC was observed in 1.6% of LTx patients. Male sex was predominant, but the proportion of women was considerably higher than in the literature. Women were diagnosed later than men, but PSC was more severe in men, including CCA in explants. The prevalence of IBD was 73%. PSC was diagnosed later in IBD patients. The median time from the diagnosis of IBD to the diagnosis of PSC was 9.8 years. Diabetes was significantly more common in patients without IBD. Aspartate transferase was 1.6 times higher in PSC patients with IBD. Esophageal varices were more frequent in non-IBD patients. The most prevalent treatment before LTx was ursodeoxycholic acid. Most men (88%) were treated endoscopically for dominant stenosis prior to LTx. CCA was an incidental finding in two patients with satisfactory survival. The survival of our PSC patients was better than that of LTx patients with other indications at our service. Survival was 81.9% (1 year) and 78.8% (5 years). PSC recurred in 5.88%.

In our cohort of 34 PSC patients submitted to LTx (2002-2023), the proportion of women was unusually high. CCA patients had satisfactory survival, despite the recurrence of PSC. In patients with both PSC and IBD, the disease was less severe.

Our study raises the hypothesis that early-stage CCA may be an acceptable indication for LTx. The observed differences in severity in the male sex and the high proportion of women in the cohort require further investigations into the genetic profile of this population.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Filipec Kanizaj T, Croatia; Janczewska E, Poland S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Visseren T, Erler NS, Polak WG, Adam R, Karam V, Vondran FWR, Ericzon BG, Thorburn D, IJzermans JNM, Paul A, van der Heide F, Taimr P, Nemec P, Pirenne J, Romagnoli R, Metselaar HJ, Darwish Murad S; European Liver and Intestine Transplantation Association (ELITA). Recurrence of primary sclerosing cholangitis after liver transplantation - analysing the European Liver Transplant Registry and beyond. Transpl Int. 2021;34:1455-1467. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Broomé U, Olsson R, Lööf L, Bodemar G, Hultcrantz R, Danielsson A, Prytz H, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Wallerstedt S, Lindberg G. Natural history and prognostic factors in 305 Swedish patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 1996;38:610-615. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 596] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 633] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liang H, Manne S, Shick J, Lissoos T, Dolin P. Incidence, prevalence, and natural history of primary sclerosing cholangitis in the United Kingdom. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7116. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Carey EJ, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 2015;386:1565-1575. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 357] [Article Influence: 39.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Radford-Smith DE, Selvaraj EA, Peters R, Orrell M, Bolon J, Anthony DC, Pavlides M, Lynch K, Geremia A, Bailey A, Culver EL, Probert F. A novel serum metabolomic panel distinguishes IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis from primary sclerosing cholangitis. Liver Int. 2022;42:1344-1354. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fosby B, Melum E, Bjøro K, Bennet W, Rasmussen A, Andersen IM, Castedal M, Olausson M, Wibeck C, Gotlieb M, Gjertsen H, Toivonen L, Foss S, Makisalo H, Nordin A, Sanengen T, Bergquist A, Larsson ME, Soderdahl G, Nowak G, Boberg KM, Isoniemi H, Keiding S, Foss A, Line PD, Friman S, Schrumpf E, Ericzon BG, Höckerstedt K, Karlsen TH. Liver transplantation in the Nordic countries - An intention to treat and post-transplant analysis from The Nordic Liver Transplant Registry 1982-2013. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:797-808. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ponsioen CY, Assis DN, Boberg KM, Bowlus CL, Deneau M, Thorburn D, Aabakken L, Färkkilä M, Petersen B, Rupp C, Hübscher SG; PSC Study Group. Defining Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: Results From an International Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis Study Group Consensus Process. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1764-1775.e5. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nardelli MJ, Bittencourt PL, Cançado GGL, Faria LC, Villela-Nogueira CA, Rotman V, Silva de Abreu E, Maria Farage Osório F, Evangelista AS, Sampaio Costa Mendes L, Ferraz de Campos Mazo D, Hyppolito EB, de Souza Martins A, Codes L, Signorelli IV, Perez Medina Gomide G, Agoglia L, Alexandra Pontes Ivantes C, Ferreira de Almeida E Borges V, Coral GP, Eulira Fontes Rezende R, Lucia Gomes Ferraz M, Raquel Benedita Terrabuio D, Luiz Rachid Cançado E, Couto CA. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis in the Highly Admixed Brazilian Population. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;2021:7746401. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Weismüller TJ, Trivedi PJ, Bergquist A, Imam M, Lenzen H, Ponsioen CY, Holm K, Gotthardt D, Färkkilä MA, Marschall HU, Thorburn D, Weersma RK, Fevery J, Mueller T, Chazouillères O, Schulze K, Lazaridis KN, Almer S, Pereira SP, Levy C, Mason A, Naess S, Bowlus CL, Floreani A, Halilbasic E, Yimam KK, Milkiewicz P, Beuers U, Huynh DK, Pares A, Manser CN, Dalekos GN, Eksteen B, Invernizzi P, Berg CP, Kirchner GI, Sarrazin C, Zimmer V, Fabris L, Braun F, Marzioni M, Juran BD, Said K, Rupp C, Jokelainen K, Benito de Valle M, Saffioti F, Cheung A, Trauner M, Schramm C, Chapman RW, Karlsen TH, Schrumpf E, Strassburg CP, Manns MP, Lindor KD, Hirschfield GM, Hansen BE, Boberg KM; International PSC Study Group. Patient Age, Sex, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype Associate With Course of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1975-1984.e8. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 311] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lindkvist B, Benito de Valle M, Gullberg B, Björnsson E. Incidence and prevalence of primary sclerosing cholangitis in a defined adult population in Sweden. Hepatology. 2010;52:571-577. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 126] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ahrendt SA, Pitt HA. Sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1996;3:431-441. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Williamson KD, Chapman RW. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a clinical update. Br Med Bull. 2015;114:53-64. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fausa O, Schrumpf E, Elgjo K. Relationship of inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Semin Liver Dis. 1991;11:31-39. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 212] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Moncrief KJ, Savu A, Ma MM, Bain VG, Wong WW, Tandon P. The natural history of inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis after liver transplantation--a single-centre experience. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:40-46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tanaka A, Mertens JC. Ulcerative Colitis with and without Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: Two Different Diseases? Inflamm Intest Dis. 2016;1:9-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Angulo P, Peter JB, Gershwin ME, DeSotel CK, Shoenfeld Y, Ahmed AE, Lindor KD. Serum autoantibodies in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2000;32:182-187. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Saadi M, Yu C, Othman MO. A Review of the Challenges Associated with the Diagnosis and Therapy of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2014;2:45-52. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wunsch E, Trottier J, Milkiewicz M, Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Hirschfield GM, Barbier O, Milkiewicz P. Prospective evaluation of ursodeoxycholic acid withdrawal in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2014;60:931-940. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Eliasson J, Lo B, Scramm C, Chazouilleres O, Folseraas T, Beuers U, Ytting H. Survey uncovering variations in the management of primary sclerosing cholangitis across Europe. JHEP Rep. 2022;4:100553. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lindor KD, Kowdley KV, Harrison ME; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG Clinical Guideline: Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:646-59; quiz 660. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 294] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chapman MH, Thorburn D, Hirschfield GM, Webster GGJ, Rushbrook SM, Alexander G, Collier J, Dyson JK, Jones DE, Patanwala I, Thain C, Walmsley M, Pereira SP. British Society of Gastroenterology and UK-PSC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 2019;68:1356-1378. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 138] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Associação Europeia para o Estudo do Fígado. Recomendações de Orientação Clínica da EASL: Abordagem de doenças hepáticas colestáticas. J Hepatol. 2009;51:237-267. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Lindor KD, Kowdley KV, Luketic VA, Harrison ME, McCashland T, Befeler AS, Harnois D, Jorgensen R, Petz J, Keach J, Mooney J, Sargeant C, Braaten J, Bernard T, King D, Miceli E, Schmoll J, Hoskin T, Thapa P, Enders F. High-dose ursodeoxycholic acid for the treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2009;50:808-814. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 448] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lopens S, Krawczyk M, Papp M, Milkiewicz P, Schierack P, Liu Y, Wunsch E, Conrad K, Roggenbuck D. The search for the Holy Grail: autoantigenic targets in primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with disease phenotype and neoplasia. Auto Immun Highlights. 2020;11:6. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Boonstra K, van Erpecum KJ, van Nieuwkerk KM, Drenth JP, Poen AC, Witteman BJ, Tuynman HA, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is associated with a distinct phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2270-2276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 136] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Boonstra K, Weersma RK, van Erpecum KJ, Rauws EA, Spanier BW, Poen AC, van Nieuwkerk KM, Drenth JP, Witteman BJ, Tuynman HA, Naber AH, Kingma PJ, van Buuren HR, van Hoek B, Vleggaar FP, van Geloven N, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY; EpiPSCPBC Study Group. Population-based epidemiology, malignancy risk, and outcome of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2013;58:2045-2055. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 433] [Article Influence: 39.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Song J, Li Y, Bowlus CL, Yang G, Leung PSC, Gershwin ME. Cholangiocarcinoma in Patients with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC): a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2020;58:134-149. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Elgenidy A, Afifi AM, Jalal PK. Survival and Causes of Death among Patients with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma in the United States from 2000 to 2018. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31:2169-2176. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |