Published online Nov 27, 2020. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i11.1067

Peer-review started: July 27, 2020

First decision: September 21, 2020

Revised: October 4, 2020

Accepted: October 26, 2020

Article in press: October 26, 2020

Published online: November 27, 2020

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is a significant complication of cirrhosis. Numerous medical, surgical, and endoscopic treatment modalities have been proposed with varied satisfactory results. In a few small studies, GAVE and associated anemia have resolved after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT).

To assess the impact of OLT on the resolution of GAVE and related anemia.

We retrospectively reviewed clinical records of adult patients with GAVE who underwent OLT between September 2012 and September 2019. Demographics and other relevant clinical findings were collected, including hemoglobin levels and upper endoscopy findings before and after OLT. The primary outcome was the resolution of GAVE and its related anemia after OLT.

Sixteen patients were identified. Mean pre-OLT Hgb was 7.7 g/dL and mean 12 mo post-OLT Hgb was 11.9 g/dL, (P = 0.001). Anemia improved (defined as Hgb increased by 2g) in 87.5% of patients within 6 to 12 mo after OLT and resolved completely in half of the patients. Post-OLT esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed in 10 patients, and GAVE was found to have resolved entirely in 6 of those patients (60%).

Although GAVE and associated anemia completely resolved in the majority of our patients after OLT, GAVE persisted in a few patients after transplant. Further studies in a large group of patients are necessary to understand the causality of disease and to better understand the factors associated with the persistence of GAVE post-transplant.

Core Tip: In this retrospective study, cirrhotic patients who had gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) with anemia and underwent orthotopic liver transplant (OLT) between September 2012 and September 2019 were reviewed to evaluate the impact of OLT on resolution of GAVE and associated anemia. A total of 296 patients underwent OLT during the study period; sixteen patients had GAVE. Anemia improved in the majority of patients in 6 to 12 mo post-OLT, and of the 10 patients who had a post-OLT esophagogastroduodenoscopy, GAVE was found to have completely resolved in 6 of those patients. We concluded that GAVE and associated anemia completely resolved in the majority of our patients post-OLT.

- Citation: Emhmed Ali S, Benrajab KM, Dela Cruz AC. Outcome of gastric antral vascular ectasia and related anemia after orthotopic liver transplantation. World J Hepatol 2020; 12(11): 1067-1075

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v12/i11/1067.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i11.1067

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is frequently found in patients with cirrhosis. The estimated prevalence in cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is around 6%, and in cirrhotic patients without apparent upper GI bleeding is about 12%[1]. Another study found that GAVE was present in 1 in 40 of cirrhotic patients who underwent screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) during liver transplant evaluation[2]. The clinical presentation extends from occult hemorrhage to transfusion-dependent chronic iron deficiency anemia.

Diagnosed endoscopically, GAVE lesions are located primarily in the antrum of the stomach[3] and appear as red spots that are either organized in stripes that project radially from the pylorus (“watermelon stomach”)[4,5], or organized in a diffuse punctate (“honeycomb”) pattern[6]. The exact etiology of GAVE remains unclear, although several hypotheses have been proposed, including mechanical stress, hemodynamic alterations, and humoral and autoimmune factors[7-9]. Numerous medical, surgical, and endoscopic treatment modalities such as endoscopic band ligation, endoscopic thermal therapy with argon plasma coagulation (APC), and radiofrequency ablation have been proposed with varying satisfactory results[10-15]. In a few small studies, GAVE and associated anemia have resolved after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT)[2,16,17].

The aim of this study was to further investigate the influence of OLT on the resolution of GAVE and associated anemia.

A retrospective chart review was conducted of all adult patients with diagnosis of cirrhosis and GAVE who underwent OLT at the University of Kentucky Medical Center (UKMC) between September 2012 and September 2019. Patient demographics; body mass index (BMI); co-morbidities; Model of End-stage Liver Disease-sodium (MELD-Na) score at the time of GAVE diagnosis; etiology of cirrhosis; use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI); GAVE presentation; type of endoscopic treatment utilized; lowest hemoglobin (Hgb) pre-OLT; hemoglobin at 3 mo, 6 mo, 9 mo, and 12 mo post-OLT; and post-OLT EGD findings were collected.

All the data mentioned above were collected from the patient's electronic medical records and stored in a password-protected excel sheet for analysis. The diagnosis of GAVE was obtained from the endoscopy reports. A single endoscopist/hepatologist independently reviewed all endoscopic images to confirm report findings. The primary outcome was the resolution of GAVE and associated anemia post-OLT.

This study was approved by the UKMC Institutional Review Board. No organs from executed prisoners were used.

Of 296 patients who underwent OLT during the study period, 16 (5.4%) had diagnosis of GAVE.

The individual patient cases are summarized in Table 1. All Caucasians, with the majority being female (62.5%) with a mean age of 56.5 years and mean BMI of 31.6. The average MELD-Na score at the time of GAVE diagnosis was 20.4. The most common etiology of cirrhosis was Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH, 44%).

| Patient No. | Age | Gender | BMI | Etiology of liver disease | MELD-Na score at GAVE diagnosis | Pre-OLT Hgb (g/dL) | GAVE pattern | Endoscopic therapy | Resolution of GAVE post-OLT |

| 1 | 66 | F | 33.7 | NASH | 26 | 8 | Diffuse punctate GAVE | APC | Yes |

| 2 | 55 | F | 28 | cryptogenic | 15 | 8.7 | Pre-OLT: Striped GAVEPost-OLT: Nodular polypoid GAVE with exudate | None | No |

| 3 | 50 | M | 42.7 | NASH | 32 | 7 | Linear/striped GAVE | APC | Yes |

| 4 | 57 | F | 32.9 | cryptogenic | 13 | 7.2 | Striped and nodular GAVE | Banding | Yes |

| 5 | 59 | F | 35.7 | NASH | 14 | 6.7 | Pre and post-OLT: Nodular polypoid GAVE with exudate | Banding | No |

| 6 | 51 | M | 23 | Alcohol | 30 | 7.1 | Diffuse punctate GAVE | APC | Yes |

| 7 | 51 | M | 27 | NASH | 23 | 7.2 | Diffuse punctate GAVE | APC | Yes |

| 8 | 57 | F | 22 | Alcohol | 23 | 7.5 | Diffuse punctate GAVE | None | Yes |

| 9 | 59 | F | 32.6 | NASH | 31 | 7.7 | Diffuse punctate GAVE | Banding | Yes |

| 10 | 40 | M | 36.6 | Alcohol, HCV | Post-OLT diagnosis | 6.9 | Post-OLT: Linear striped; then polypoid GAVE | None | No |

| 11 | 55 | M | 30.8 | PSC | 13 | 8.8 | Nodular polypoid GAVE with exudate | None | Yes |

| 12 | 58 | M | 17.8 | Alcohol | 12 | 7.3 | Diffuse punctate GAVE | None | Yes |

| 13 | 62 | F | 47.6 | HCV | 30 | 7.6 | Linear/striped GAVE | None | Yes |

| 14 | 57 | F | 25.5 | Budd Chiari syndrome | Post-OLT diagnosis | Post-OLT: Patchy mild punctate GAVE | None | No | |

| 15 | 67 | F | 35.5 | NASH | 15 | 9.6 | Patchy mild punctate GAVE | None | Yes |

| 16 | 60 | F | 32.5 | NASH | 8 | 7.5 | Linear/striped GAVE | APC | Yes |

Twelve patients (75%) had concomitant portal hypertensive gastropathy, and 13 (81%) had chronic kidney disease (defined as a GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for > 3 mo).

Thirteen patients (81%) were on a PPI. All patients presented with anemia, with 50% have at least one episode of overt bleeding requiring a blood transfusion prior to transplant. Five of those without overt bleed had iron deficiency anemia. Half of the patients were treated endoscopically, with APC being the most common treatment (31%), and 25 % of patients underwent banding.

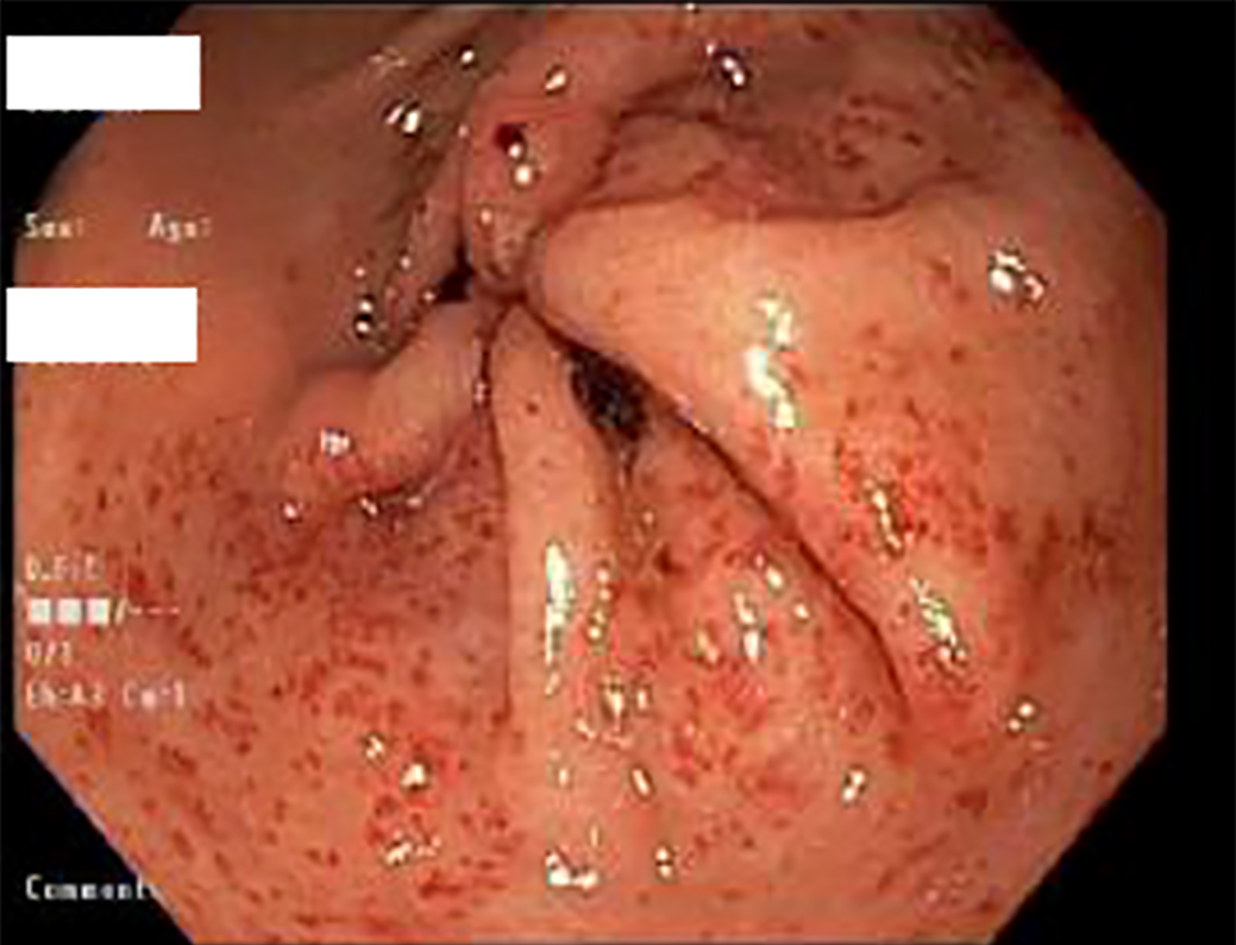

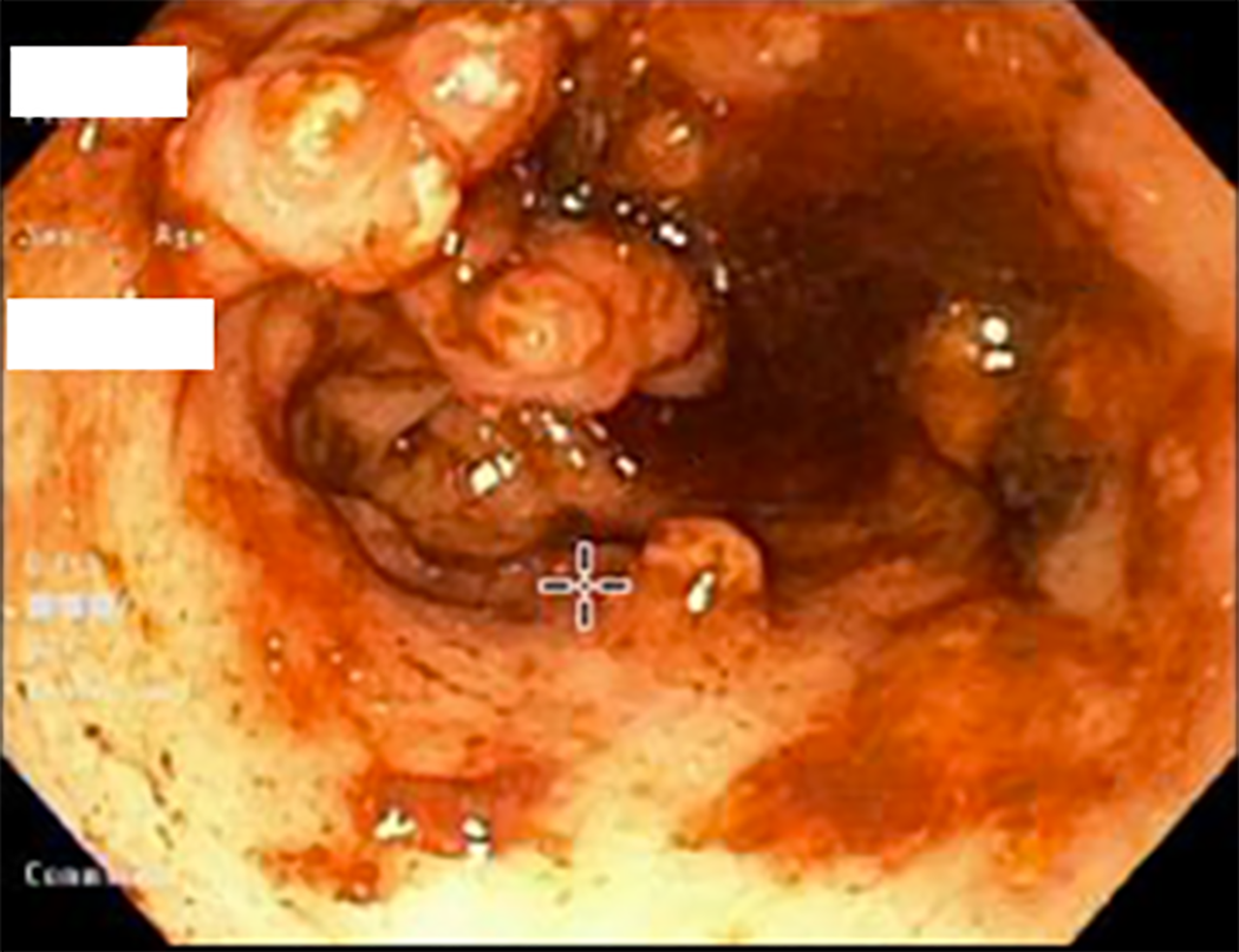

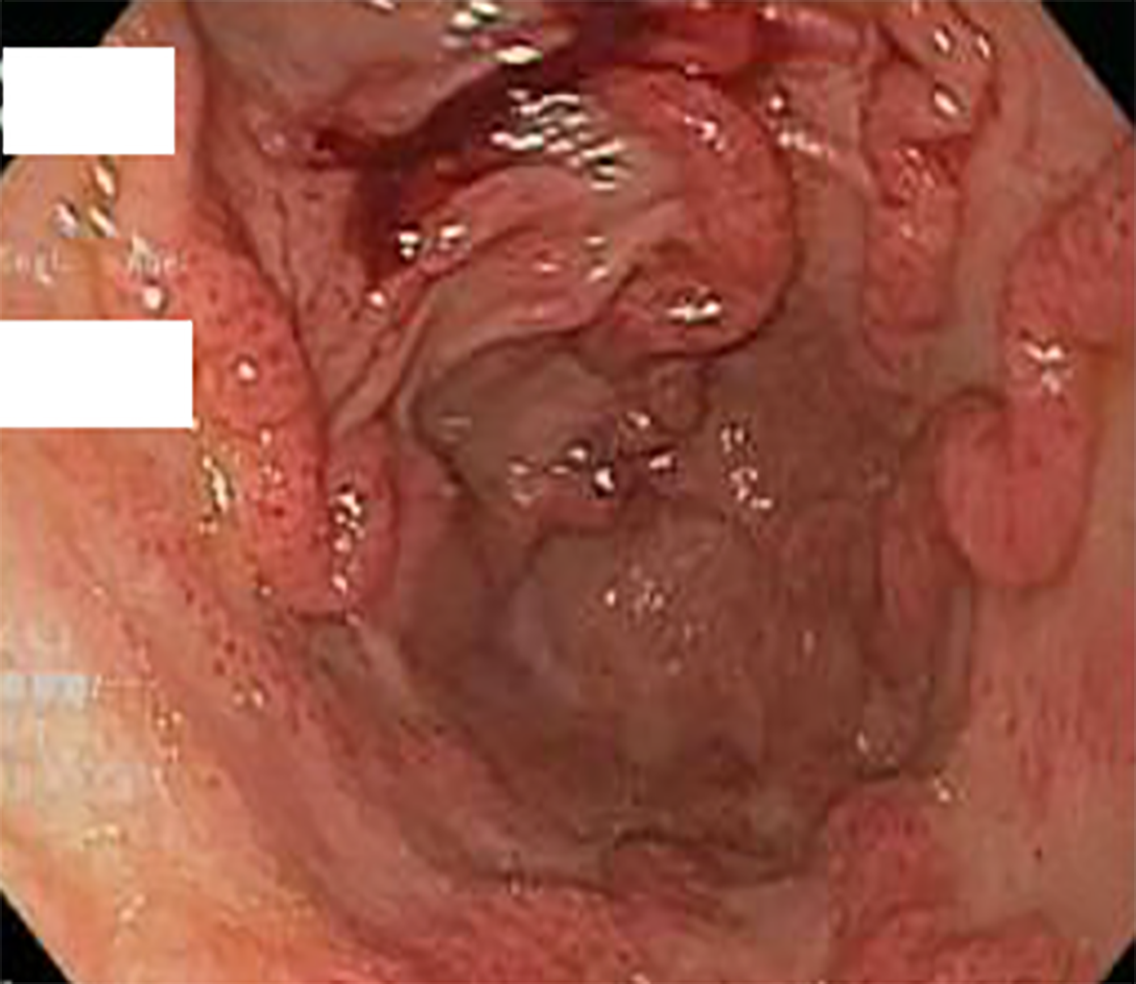

The pattern of GAVE varied in our patient cohort: Six patients had diffuse punctate GAVE (Figure 1), five patients had linear/striped pattern (Figure 2), two had patchy mild punctate GAVE, two patients had nodular polypoid GAVE characterized by polypoid lesions with exudate (Figure 3), and one had nodular striped GAVE (Figure 4). The patterns evolved in two patients, with the initial EGD showing a linear pattern and subsequent EGD showing a nodular/polypoid GAVE.

Mean pre-OLT Hgb was 7.7 g/dL compared to 11.9 g/dL at 12 mo post-OLT (P = 0.001). Anemia improved in 87.5 % (defined as Hgb increase by 2g) of patients (n = 14) & resolved entirely in 50 % of patients within 6 to 12 mo after OLT.

Only two patients required blood transfusion after three months post-transplant. One patient was five months, and the other patient was three years post-OLT; however, neither had evidence of bleeding.

Post-OLT EGD was performed in 10 patients. The mean time between OLT and post-OLT EGD was 27.9 mo. Among the 10 patients who underwent post-OLT EGD, GAVE was found to have resolved entirely in six patients (60%).

It is unclear why GAVE persisted in four out of ten patients who underwent post-OLT EGD. The first patient had psoriatic arthropathy. The second patient had GAVE sixteen years after transplant and had underlying polycythemia vera and chronic splenic thrombosis post-transplant with varices. The third patient had recurrent biopsy-proven cirrhosis. The fourth patient had persistent nodular GAVE, which required two endoscopic band ligations at two and ten weeks post-OLT with an endoscopic resolution of GAVE and associated anemia at six months post-OLT. The pattern of post-transplant GAVE varied in these four patients. Two patients had polypoid GAVE, one patient had linear GAVE, which later evolved into polypoid GAVE, and one patient had patchy mild punctate GAVE.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia is a common finding in patients with cirrhosis and often presents as chronic anemia. The endoscopic pathognomonic feature of GAVE is columns of red tortuous ectatic vessels along the folds of the antrum[18]. Histologically, GAVE is characterized by mucosal vascular ectasia, spindle cell proliferation, fibrohyalinosis, and fibrin thrombi[19]. It is a disease with focal distribution[20]. Therefore, a negative biopsy does not rule out GAVE[20].

Although GAVE has been historically described as a "watermelon stomach," the diffuse pattern of GAVE endoscopically was found to be more frequent in cirrhotic patients in one study[5]. In contrast, the classic watermelon form was found to be more common in non-cirrhotic patients[21]. In our cohort, 50% of patients were found to have diffuse punctate GAVE, 31% had a linear/striped pattern, and 19% with nodular type. The gender distribution in our study seems to be similar to other studies. In our study, the cirrhotic GAVE patients were predominately female (62.5%) with a mean age of 56.2 years. Other studies have shown a female predominance (71%) of GAVE in cirrhotic patients with a mean age of 73 years, and a male predominance (75%) in non-cirrhotic GAVE patients, with a mean age of 65 years[22,23].

The exact pathophysiological mechanism that leads to GAVE remains unclear. It is highly essential to differentiate GAVE from portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) because they are treated differently. PHG mainly causes mucosal changes in the fundus and corpus[20], whereas GAVE is limited to antrum[18]. It is possible that portal hypertension has no significant role in the development of GAVE for several reasons, such as absence of correlation between the severity of portal hypertension and degree of vascular ectasia[6], and non-resolution of GAVE after reduction in portal pressure[23,24]. Quintero et al[6] linked low levels of pepsinogen, high levels of gastrin, and achlorhydria, with GAVE, and other studies have reported improvement in GAVE and reduction in gastrin levels after cessation of proton pump inhibitor[25]. In our study, 13 patients (81%) were taking proton pump inhibitors before and after OLT. Prostaglandin E2 has a gastric vasodilator effect and has been considered to play a role in the development of GAVE[8]. Another study by Lowes et al[7] found a proliferation of neuroendocrine cells that secretes 5-hydroxytryptamine and vasoactive peptide close to the ectatic blood vessels. Mechanical stress theory has been suggested by Charneua et al[9] to be playing a role in cirrhotic GAVE patients after they found abnormal motility patterns on antral motility studies. In non-cirrhotic GAVE patients, many other medical conditions have been described, such as autoimmune disease, acute myeloid leukemia, hypertension, chronic renal failure, ischemic heart disease, bone marrow transplantation, scleroderma, and familial Mediterranean fever[22,26-28]. The most frequent associated autoimmune conditions are connective tissue diseases followed by Raynaud’s phenomenon and sclerodactyly[22].

Bleeding GAVE can be very problematic and challenging to manage. Several endoscopic interventions and medications are available[10-15]. In three previous small studies, GAVE and associated anemia resolved after liver transplantation[2,16,17]. Reduction in portal hypertension via medical use of beta-blockers or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement has failed to accomplish resolution of GAVE or associated anemia in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension[23,24]. None of our patients had TIPS before the diagnosis of GAVE. One patient had TIPS a month just before the transplant, and TIPS was done eighteen months after diagnosis of GAVE for refractory ascites. Before the transplant, eight of our patients underwent endoscopic treatment with APC as the most commonly used method. None of our patients received medical treatment, such as Tranexamic acid.

Our study further supports that GAVE in cirrhotic patients may resolve after OLT. Six out of ten patients who underwent post-OLT EGD have complete resolution of GAVE. The potential explanations for persistent GAVE among the other four patients include an underlying rheumatologic condition which can also cause non-cirrhotic GAVE in the first patient, underlying chronic splenic vein thrombosis in the second patient, recurrent cirrhosis in the third patient, and delayed resolution of GAVE after transplant since GAVE was seen fairly recently post-transplant, noted at two and ten weeks post-transplant with the resolution of anemia in the fourth patient.

The associated anemia entirely resolved in half of our patients and improved in 87.5% of patients six to twelve months after OLT. Anemia is common in cirrhotic patients; however, it is usually complex, and may be influenced by several factors, including etiology of cirrhosis and degree of portal hypertension[29,30]. Portal hypertension and hypersplenism can be contributing factors to anemia in cirrhosis; however, the magnitude of the effect is unclear[31,32]. Furthermore, Vincent et al[17] reported resolution of GAVE and anemia in 2 patients post OLT even with persistent evidence of portal hypertension.

One would speculate that the associated resolution of liver dysfunction would lead to the resolution of GAVE after transplant. GAVE was frequently found in patients with more advanced liver disease and has been reported to resolve after liver transplantation[2,16,17]. In our cohort at the time of GAVE diagnosis, the mean MELD-NA score was 20.4.

The limitations of the current study include retrospective design with a small sample size. EGDs were also performed by several different endoscopists performed EGDs; however, we attempted to control for this by having one endoscopist/ hepatologist review all endoscopic images. Also, only 10 patients had undergone EGD post-OLT. The patients were not treated with the same endoscopic modality, and there was no established endoscopic protocol to eradicate GAVE. Indeed, there is usually no standard treatment modality since the type of endoscopic treatment will depend on the pattern of GAVE and previous endoscopic therapies, with the preferable use of banding for most patients with nodular GAVE and APC in all other patterns of GAVE (linear and punctate GAVE). Not all patients in our cohort had histologic confirmation of GAVE, and this could raise the possibility of overlap between GAVE and PHG. Despite these limitations, this study offers the largest number of patients with GAVE who underwent liver transplantation, and our findings corroborate those from previous studies showing that GAVE and associated anemia resolve in the majority of patients who underwent liver transplantation. It also further explored the possible underlying mechanisms for persistent GAVE after OLT in four out of ten patients who had post-OLT EGD.

GAVE is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Although GAVE and associated anemia completely resolved in the majority of our patients after liver transplantation, GAVE persisted in a few patients post-OLT. Large, prospective studies using consistent diagnostic criteria for GAVE and planned follow-up EGDs after OLT are needed to better understand the factors may contribute to persistence of GAVE post-transplant.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is a well-recognized cause of gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. The etiology of GAVE remains unclear, although several humoral, autoimmune, mechanical stress, and pharmacological (proton pump inhibitor use) hypotheses have been described. Different treatment modalities have been proposed with varying results. Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT), which is often recommended for patients with significant complications due to end-stage liver disease, has also been shown to be beneficial treatment for resolution of GAVE and associated anemia in a few small studies.

To evaluate the relation between GAVE and associated anemia and OLT.

To assess the impact of OLT on resolution of the natural course of GAVE and associated anemia.

A retrospective chart review was conducted of adult patient with GAVE who underwent liver transplant between September 2012 and September 2019. Demographics and other relevant findings, including hemoglobin levels, Model of End-stage Liver Disease-sodium score, GAVE presentation, and upper endoscopy findings before and after OLT were collected.

Sixteen patients were identified, all Caucasians and predominantly female (62.5%) with a mean age of 56.5 years. The most common etiology for cirrhosis was NASH (44%). All patients presented with anemia, with 50% presenting with overt bleed and required transfusions prior to transplant. Mean pre-OLT Hgb was 7.7, and the mean 12 mo post-OLT Hgb was 11.9 (P = 0.001). Anemia improved in 87.5% of patients (n = 14) within 6 to 12 mo after OLT and resolved completely in half of the patients. Post-OLT esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed in 10 patients, and GAVE resolved entirely in 6 of those patients (60%).

Although GAVE and associated anemia completely resolved in the majority of our patients after liver transplantation, GAVE persisted in a few patients after transplant.

Large prospective studies are needed to better understand what factors may contribute to persistent GAVE post-liver transplant.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Coelho J, Manrai M S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Swanson E, Mahgoub A, MacDonald R, Shaukat A. Medical and endoscopic therapies for angiodysplasia and gastric antral vascular ectasia: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:571-582. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ward EM, Raimondo M, Rosser BG, Wallace MB, Dickson RD. Prevalence and natural history of gastric antral vascular ectasia in patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:898-900. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stotzer PO, Willén R, Kilander AF. Watermelon stomach: not only an antral disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:897-900. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chatterjee S. Watermelon stomach. CMAJ. 2008;179:162. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ito M, Uchida Y, Kamano S, Kawabata H, Nishioka M. Clinical comparisons between two subsets of gastric antral vascular ectasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:764-770. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Quintero E, Pique JM, Bombi JA, Bordas JM, Sentis J, Elena M, Bosch J, Rodes J. Gastric mucosal vascular ectasias causing bleeding in cirrhosis. A distinct entity associated with hypergastrinemia and low serum levels of pepsinogen I. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:1054-1061. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 189] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lowes JR, Rode J. Neuroendocrine cell proliferations in gastric antral vascular ectasia. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:207-212. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Saperas E, Perez Ayuso RM, Poca E, Bordas JM, Gaya J, Pique JM. Increased gastric PGE2 biosynthesis in cirrhotic patients with gastric vascular ectasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:138-144. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Charneau J, Petit R, Calès P, Dauver A, Boyer J. Antral motility in patients with cirrhosis with or without gastric antral vascular ectasia. Gut. 1995;37:488-492. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hsu WH, Wang YK, Hsieh MS, Kuo FC, Wu MC, Shih HY, Wu IC, Yu FJ, Hu HM, Su YC, Wu DC. Insights into the management of gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach). Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756283X17747471. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Prachayakul V, Aswakul P, Leelakusolvong S. Massive gastric antral vascular ectasia successfully treated by endoscopic band ligation as the initial therapy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:135-137. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Friedel D. Potential role of new technological innovations in nonvariceal hemorrhage. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;11:443-453. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Magee C, Lipman G, Alzoubaidi D, Everson M, Sweis R, Banks M, Graham D, Gordon C, Lovat L, Murray C, Haidry R. Radiofrequency ablation for patients with refractory symptomatic anaemia secondary to gastric antral vascular ectasia. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:217-224. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fuccio L, Mussetto A, Laterza L, Eusebi LH, Bazzoli F. Diagnosis and management of gastric antral vascular ectasia. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:6-13. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chiu YC, Lu LS, Wu KL, Tam W, Hu ML, Tai WC, Chiu KW, Chuah SK. Comparison of argon plasma coagulation in management of upper gastrointestinal angiodysplasia and gastric antral vascular ectasia hemorrhage. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:67. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Allamneni C, Alkurdi B, Naseemuddin R, McGuire BM, Shoreibah MG, Eckhoff DE, Peter S. Orthotopic liver transplantation changes the course of gastric antral vascular ectasia: a case series from a transplant center. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:973-976. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vincent C, Pomier-Layrargues G, Dagenais M, Lapointe R, Létourneau R, Roy A, Paré P, Huet PM. Cure of gastric antral vascular ectasia by liver transplantation despite persistent portal hypertension: a clue for pathogenesis. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:717-720. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Novitsky YW, Kercher KW, Czerniach DR, Litwin DE. Watermelon stomach: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:652-661. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Payen JL, Calès P, Voigt JJ, Barbe S, Pilette C, Dubuisson L, Desmorat H, Vinel JP, Kervran A, Chayvialle JA. Severe portal hypertensive gastropathy and antral vascular ectasia are distinct entities in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:138-144. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 121] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Burak KW, Lee SS, Beck PL. Portal hypertensive gastropathy and gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) syndrome. Gut. 2001;49:866-872. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 128] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chaves DM, Sakai P, Oliveira CV, Cheng S, Ishioka S. Watermelon stomach: clinical aspects and treatment with argon plasma coagulation. Arq Gastroenterol. 2006;43:191-195. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gostout CJ, Viggiano TR, Ahlquist DA, Wang KK, Larson MV, Balm R. The clinical and endoscopic spectrum of the watermelon stomach. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:256-263. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 180] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Spahr L, Villeneuve JP, Dufresne MP, Tassé D, Bui B, Willems B, Fenyves D, Pomier-Layrargues G. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in cirrhotic patients: absence of relation with portal hypertension. Gut. 1999;44:739-742. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 138] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kamath PS, Lacerda M, Ahlquist DA, McKusick MA, Andrews JC, Nagorney DA. Gastric mucosal responses to intrahepatic portosystemic shunting in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:905-911. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 156] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nakade Y, Ozeki T, Kanamori H, Inoue T, Yamamoto T, Kobayashi Y, Ishii N, Ohashi T, Ito K, Yoneda M. A Case of Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia Which Was Aggravated by Acid Reducer. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2017;11:64-71. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tobin RW, Hackman RC, Kimmey MB, Durtschi MB, Hayashi A, Malik R, McDonald MF, McDonald GB. Bleeding from gastric antral vascular ectasia in marrow transplant patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:223-229. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sebastian S, O'Morain CA, Buckley MJ. Review article: current therapeutic options for gastric antral vascular ectasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:157-165. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Takahashi T, Miya T, Oki M, Sugawara N, Yoshimoto M, Tsujisaki M. Severe hemorrhage from gastric vascular ectasia developed in a patient with AML. Int J Hematol. 2006;83:467-468. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Singh S, Manrai M, V S P, Kumar D, Srivastava S, Pathak B. Association of liver cirrhosis severity with anemia: does it matter? Ann Gastroenterol. 2020;33:272-276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Peck-Radosavljevic M. Hypersplenism. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:317-323. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | DuBois B, Mobley D, Chick JFB, Srinivasa RN, Wilcox C, Weintraub J. Efficacy and safety of partial splenic embolization for hypersplenism in pre- and post-liver transplant patients: A 16-year comparative analysis. Clin Imaging. 2019;54:71-77. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhu J, Chen X, Hu X, Zhu H, He C. A Comparative Study of Surgical Splenectomy, Partial Splenic Embolization, and High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound for Hypersplenism. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:467-474. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |