Published online Dec 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i47.10316

Peer-review started: September 20, 2016

First decision: October 10, 2016

Revised: October 30, 2016

Accepted: December 2, 2016

Article in press: December 2, 2016

Published online: December 21, 2016

Processing time: 90 Days and 14.9 Hours

Oesophageal cancer affects more than 450000 people worldwide and despite continued medical advancements the incidence of oesophageal cancer is increasing. Oesophageal cancer has a 5 year survival of 15%-25% and now globally attempts are made to more aggressively diagnose and treat Barrett’s oesophagus the known precursor to invasive disease. Currently diagnosis the of Barrett’s oesophagus is predominantly made after endoscopic visualisation and histopathological confirmation. Minimally invasive techniques are being developed to improve the viability of screening programs. The management of Barrett’s oesophagus can vary greatly dependent on the presence and severity of dysplasia. There is no consensus between the major international medical societies to determine and agreed surveillance and intervention pathway. In this review we analysed the current literature to demonstrate the evolving management of metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett’s epithelium.

Core tip: Barrett's esophagus is a premalignant condition. Its malignant sequela, esophagogastric junctional adenocarcinoma, has a mortality rate of over 85%. The risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma in people who have Barrett's esophagus has been estimated to be 6-8 per 1000 person-years. Early identification of Barrett’s and adjusted management is very important to decrease oesophageal cancer related deaths worldwide.

- Citation: Evans RPT, Mourad MM, Fisher SG, Bramhall SR. Evolving management of metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett's epithelium. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(47): 10316-10324

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i47/10316.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i47.10316

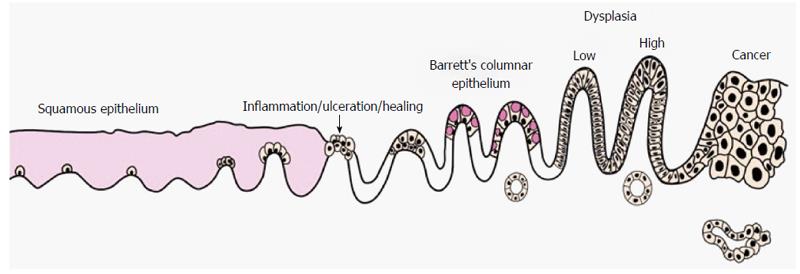

Differentiation to columnar cells that are normally found in the more distal gastrointestinal tract is the result of over exposure to acid and bile reflux in the lower oesophagus. Cells that have undergone metaplasia are at a greater risk of developing dysplasia and subsequently invasive cancer (Figure 1). Barrett’s oesophagus (BO) is defined as an oesophagus in which any portion of the normal distal squamous epithelial lining has been replaced by metaplastic columnar epithelium, which is clearly visible endoscopically (≥ 1 cm) above the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ) and confirmed histopathologically on oesophageal biopsies[1]. The potential for patients with BO to develop invasive cancer has led to the development of national surveillance programs to identify and manage patients at risk of oesophageal cancer.

Current meta-analysis suggests that the overall incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma occurring in BO is around 3-17 per 1000 person years[2-9]. The proportion of the oesophagus affected by BO is a key BO determinant in cancer risk. Annual cancer transition rates in BO have been estimated at 0.22%, 0.03% and 0.01% for long (> 3 cm), short (1-3 cm) and ultra-short (1 cm) BO[10]. At such rates the number of patients who would need to undergo an upper endoscopy to find one cancer per year is 450 patients with a long-segment, 3440 with a short-segment and 12 365 with an ultra-short-segment BO[10]. Risk of transition is not only dependent on the extent of BO but the severity of dysplasia. The annual risk of oesophageal cancer is approximately 0.25% for patients without dysplasia and 6% for patients with high-grade dysplasia[11].

Oesophageal cancer affects more than 450000 people worldwide and despite continued medical advancements the incidence of oesophageal cancer is increasing[12-16]. In England and Wales from 1971 to 2001 the incidence of oesophageal cancer rose 40% every 5 years[15]. Oesophageal cancer has a 5 year survival of 15%-25% and attempts to identify, survey and treat BO are to reduce this incidence[14,17]. BO is largely asymptomatic and the sub-population that present for medical attention may well differ from the total population of BO sufferers[17]. This makes it particularly challenging to determine the true prevalence of BO which is unknown but estimated to be approximately 1.6%-8.0%[18,19].

Reflux is a common problem with prevalence estimates 8.8%-25.9% in Europe, 18.1%-27.8% in North America, 2.5%-7.8% in East Asia, 8.7%-33.1% in the Middle East, 11.6% in Australia and 23.0% in South America. In the United Kingdom and United States the incidence was approximately 5 per 1000 person-years[20]. Not all patients with reflux will develop BO but reflux is the presumed precipitant in the majority of cases. In patients suffering from reflux the male gender, increasing age, an increased BMI, increased waist circumference independent of BMI, duration of reflux symptoms, and presence of a hiatal hernia with all associated with an increased risk of developing BO[21,22]. The risk of patients with BO developing high-grade dysplasia and oesophageal adenocarcinoma was increased in men, smokers, those with a decreased fruit and vegetable intake, and those with a long segment of Barrett’s oesophagus, but not with increased age, BMI, or a hiatal hernia[21].

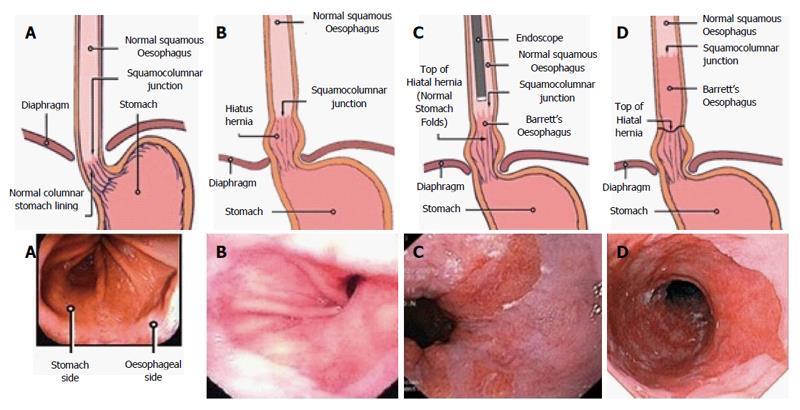

The diagnosis of BO is achieved through endoscopic visualisation and histopathological confirmation. Indications for endoscopy include symptoms of reflux, dyspepsia, dysphagia, gastrointestinal bleeding, iron deficiency anaemia and visualisation of an imaging identified abnormality. Currently standard upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is the gold standard method to diagnose BO. Trans-nasal endoscopy has also been shown to be accurate and well tolerated with a sensitivity and specificity of 98% and 100% respectively[23,24]. Identification of the GOJ is key in determining the presence and extent of BO. This can be done by identifying the confluence of the distal end of the palisade vessels and the proximal end of the gastric folds however peristalsis, oesophagitis and insufflation can potentially make these landmarks inconsistent. It is important to identify the presence of an irregular Z line in order not to mistake this for BO. Despite these recognised anatomical landmarks documentation is challenging and there is the potential for inter and intra-observer variation[25-27] (Figure 2).

For initial diagnostic purposes standard white light endoscopy (WLE) Nis often used for the identification of BO. High resolution WLE has been shown to have better targeted detection of any dysplasia in BO surveillance and a higher sensitivity of detecting early neoplastic lesions[28-30]. However high resolution WLE alone does not alter the need for random biopsies when identifying BO. Chromoendoscopy has also been used to improve the detection of BO. It involves the application of methylene blue that selectively reacts with and highlights various mucosal features, theoretically improving the detection of abnormalities[31-37]. Currently advanced imaging modalities, such as chromoendoscopy or electrical chromoendoscopy, are not superior to standard white light endoscopy or high resolution WLE in BO surveillance and are therefore not recommended for routine use[1,29]. Narrow band imaging has also been used in attempt to improve the detection of BO. A restricted spectrum of light is used to enhance capillary blood flow in order to highlight areas of metaplasia or dysplasia. It has not been shown to be superior to white light endoscopy and random biopsy in screening and is therefore not advocated for routine use[38].

The Prague Criteria were developed in order to standardise the reporting of BO in order to minimise observer variation. The Prague Criteria give explicit guidance on the endoscopic recognition of BO and grading of its extent. The criteria included assessment of the circumferential (C) and maximum (M) extent of the endoscopically visualized BO segment as well as endoscopic landmarks[39]. The use of the Prague criteria has been adopted widely and has been shown to be easily used by both experienced clinicians and trainees alike[40,41]. There has been some criticism that the criteria do not allow for detailed descriptions of short and ultra-short BO. Expansion of the Prague criteria to permit further detailed descriptions of BO islands has been suggested[42].

Histological diagnosis of BO varies from country to country. The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) defines BO as metaplastic differentiation to columnar mucosa however there is no requirement for confirmation of the presence of goblet cells[1]. This differs from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) which defines BO to be the presence of intestinal metaplasia and therefore the presence of goblet cells in oesophageal mucosal biopsies obtained from endoscopically identified areas of columnar mucosa[43]. It is important to note that the absence of goblet cells does remove the increased risk of neoplastic transformation. The presence of goblet cells can fluctuate over time in metaplasia and is inevitably affected by the number and size of biopsies taken[44]. Only endoscopic identification in required in Japan to confirm BO[45]. Despite these variations in definition treatment and surveillance modalities remain similar.

Screening in patients with BO has gained popularity as a way of identifying dysplastic changes prior to evolution into invasive malignancy and therefore potentially improving treatment outcomes. The BSG, the AGA and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) does not advocate screening the general population of reflux sufferers as it is not cost effective at identifying BO[1,43,46] and 40% of patients with oesophageal adenocarcinoma do not have chronic reflux symptoms[43]. Estimates suggest around that 1 in 4 people suffer from reflux and therefore screening nearly 80 million people in the USA and 18 million people in the UK is neither feasible or cost effective[20]. Screening guidance in high risk populations varies slightly between the United Kingdom and the United States. The BSG guidelines advise that endoscopic screening can be considered in patients with chronic gastrointestinal reflux disease (GORD) symptoms and multiple risk factors (at least three of age 50 years or older, white race, male sex, obesity).

The threshold of multiple risk factors however, should be lowered in the presence of family history including at least one first-degree relative with BO or oesophageal adenocarcinoma[1]. The AGA and ACG recommend screening for Barrett’s oesophagus in patients with multiple risk factors associated with oesophageal adenocarcinoma (age 50 years or older, male sex, white race, chronic GORD, hiatal hernia, elevated body mass index, and intra-abdominal distribution of body fat)[43,46].

New less invasive techniques are being developed; the minimally invasive cell sampling device, cytosponge coupled with immunohistochemical sampling for biomarker trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) have been described to support the diagnosis of BO. In the 93% of patients who were able to complete the test the cytosponge had a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 92% in diagnosing BO[47]. Obtaining cytology via a cytosponge also potentially allows for the identification of neoplasia using infrared microscopy but further studies are required[48].

Screening of high risk populations potentially identifies a greater number of patients with Barrett’s oesophagus however this is little evidence to show such regimens reduce the incidence rates of oesophageal malignancy. Risk modelling has been performed to potentially identify as many high risk patients as possible however often Barrett’s Oesophagus is present in patients outside current screening guidelines such as men below the age of 40 and women with nocturnal symptoms[49,50]. Potentially with further accurate modelling, and less invasive economically viable tests screening may become increasingly routine.

The visual identification of a suspicious lesion or BO should lead to a biopsy being performed. Targeted biopsies of a lesion should occur first followed by the Seattle Biopsy Protocol which entail four quadrant biopsies every 2 cm[51]. A prospective study has shown that the use of the Seattle Protocol leads to a significant increase in detection of early lesions[52]. Conversely it has also been shown that non adherence to the Seattle Protocol reduces the detection of dysplasia[53,54]. Histological analysis should clearly document the level and number of biopsies taken. The presence of the following should be documented by the pathologist; squamous mucosa, glandular mucosa, native oesophageal structures, intestinal metaplasia, glandular dysplasia (indefinite, low, high, intra-mucosal neoplasia), p53 immunostaining and presence of inflammation (acute/chronic). A summary should be included stating whether there was BO with gastric metaplasia, BO with intestinal metaplasia (± dysplasia) or no BO.

Subsequent classification of dysplasia should be done in concordance with the Vienna classification to facilitate surveillance of intervention plans[55] (Table 1). BSG guidelines currently advise that the presence of dysplasia should be confirmed by two pathologists due to the implications for diagnosis[1].

| 1 | Negative for dysplasia |

| 2 | Indefinite for dysplasia |

| 3 | Low-grade dysplasia |

| 4a | High-grade dysplasia (including carcinoma in situ) |

| 4b | Intra-mucosal carcinoma (including suspicious for invasive cancer) |

| 5 | Submucosal invasion by adenocarcinoma |

The current guidance for surveillance in non-dysplastic BO (NDBO) varies significantly across Europe and America. The BSG advise that for NDBO surveillance should occur every 3-5 years for short segment BO (SSBO, < 3 cm) BO and every 2-3 years for long segment BO (LSBO, > 3 cm)[1]. The BSG also advise that patients with histology that is indefinite for dysplasia show undergo re-biopsy at 6 mo and if no definitive dysplasia is found they should be managed as NDBO. The French Society of Digestive Endoscopy (FSDE) advocate surveillance every 5 years for SSBO (< 3 cm), every 3 years for LSBO 3-6 cm and every 2 years for LSBO > 6 cm[56]. The AGA advocate surveillance every 3-5 years for NDBO irrespective of length[43]. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) advise considering no surveillance but if required should be every 3-5 years for NDBO[57]. ACG advise 2 OGDs in the first year and then every 3 years if no dysplasia is found[46].

In patients with low-grade dysplasia on biopsy the ACG and ASGE advise repeating the OGD within 6 mo and if there is no evidence of high-grade dysplasia then extend surveillance to every year[46,57]. The AGA advise surveillance every 6-12 mo[43], the FSDE advise repeat endoscopy and if Low grade dysplasia (LGD) is confirmed then endoscopy should be performed at 6 mo, 1 year, and then every year[56]. The BSG guidelines were published in 2014 but have been subsequently updated in response to new guidance from NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). If LGD (confirmed by two pathologists) is identified again 6 mo after the initial endoscopy the patient should be offered endoscopic ablation therapy[58,59]. Duits et al[60] performed a retrospective analysis of 293 patients with LGD. After re-analysis of histology by expert opinion only 27% were confirmed to have LGD. The patients were followed up for 39 mo and had a conversion rate of 9.1%/year to high grade dysplasia or invasive neoplasia whereas the NDBO population had a conversion rate of 0.6% and 0.9%/year. A multicentre randomized control trial (RCT) of patients with LGD undergoing radio-frequency ablation (RFA) (n = 68) or surveillance (n = 68) demonstrated at follow up at 3 years 1 % of those receiving RFA has developed HGD/ invasive neoplasia whereas 26.5% of patients in the surveillance arm had developed HGD/ invasive neoplasia[61]. This data are supports a more proactive management approach in these patients.

The differences between the various guidelines are reflective of their year of publication. As new studies have been produced not all guidelines have been actively updated. Only the BSG has formally re-addressed this issue. Although French and American guidelines advocate a less aggressive approach for LGD this is unlikely to be reflective of institutional practice, which will be more regularly reviewed and updated to provide up to date local investigation and treatment guidelines.

The BSG advocate endoscopic therapy for High Grade Dysplasia (HGD) while the FSDE advise a second OGD and if HGD is confirmed endoscopic or surgical treatment should be offered at this point. The ACG advise repeat endoscopy within 3 mo and then every 3 mo or consider endoscopic therapy. The ASGE advise either repeat endoscopy within 3 mo or endoscopic therapy and the AGA advise endoscopy every 3 mo in the absence of endoscopic therapy. As endoscopic therapies improve fewer patients are undergoing oesophagectomy for HGD and early carcinoma and patients with HGD who are suitable for endoscopic therapy should be discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting to formalise care and follow up (Table 2). Similarly with LGD, the BSG guidelines are more aggressive and are the most recent published guideline.

| BSG | FSDE | AGA | ACG | ASGE | |

| No dysplasia | OGD every 3-5 yr for SSBO (< 3 cm), every 2-3 years FOR LSBO(> 3 cm) | OGD every 5 yr for SSBO (< 3 cm), every 3 yr for LSBO (3-6 cm), every 2 yr for LSBO (> 6 cm) | OGD every 3-5 yr | 2 OGDs in the first year and then every 3 yr | No surveillance but if required should be every 3-5 yr |

| Low-grade dysplasia | Repeat OGD at 6 mo, if LGD offer endoscopic therapy | Repeat OGD if LGD perform OGD at 6 mo, 1 yr, then every year | OGD every 6-12 mo | Repeat OGD within 6 mo if no HGD then OGD every year | Repeat OGD within 6 mo if no HGD then OGD every year |

| High-grade dysplasia | Offer endoscopic therapy | Repeat OGD if HGD offer endoscopic/surgical therapy | OGD every 3 mo in the absence of endoscopic therapy | Repeat OGD within 3 mo, then every 3 mo or consider | Repeat OGD within 3 mo or endoscopic therapy |

| Endoscopic therapy |

Endoscopic therapies can broadly be categorised into two groups tissue acquiring and non-tissue acquiring. Endoscopic resections (ER) are commonly performed on nodular lesions with curative intent. ER is the most accurate way of diagnosing dysplasia or early invasive disease in BO[62]. It is preferred to biopsies in surveillance due to the risk of biopsies missing HGD or invasive disease[63]. ER has an initial eradication of HGD of 90% and complete remission rate of 90% when complete excision is achieved[64]. Recurrence of NDBO at 5 years is around 39.5% and recurrence of dysplasia or cancer is 6.2%. Adverse events including stricturing can occur in up to 47%[64].

RFA is being used increasingly to treat BO and is often used in conjunction with ER to achieve optimum outcomes. Estimates show that with use RFA alone complete eradication of dysplasia can occur in 82%-91% of patients with complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia in 56%-77%[65,66]. Most studies that assess the use of combined RFA and ER show improved outcomes as compared to RFA alone[66,67]. Haidry et al[68] however, found that ER before RFA did not provide any additional benefit. RFA in combination with ER can lead to dysplasia eradication in 86-94% with complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia of 88%-90%. Stricture rates without ER are approximately 5%-6.5% and with ER are approximately 7.9%-9%[65,66,68]. Cryotherapy is a possible alternative to RFA when an ablative technique is required but has a larger complication profile than RFA and is less frequently used[69,70]. The BSG advocates the use of ER for dysplasia within visible lesions otherwise RFA is the technique of choice[1].

Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy has been the mainstay of therapy for patients with symptomatic reflux and evidence exists that PPI use reduces the risk of neoplastic progression in patients with BO[71,72]. There is no such evidence for H2 receptor antagonists[72]. Anti reflux surgery has been shown to cause regression of BO in between 22% and 35% of patients but 7%-8% of patients will progress to dysplasia despite surgery[73,74]. Antireflux surgery has not been shown to be significantly better than medical therapy in preventing progression to dysplasia or adenocarcinoma and is therefore not indicated for the treatment of BO ahead of medical therapy. Anti reflux surgery still plays an important role in symptom control from reflux in a proportion of patients.

Oesphagectomy plays a primary role in managing oesophageal cancer in patients with disease invading the submucosa or lymph nodes on diagnosis. The 90 day mortality for oesophagectomy has improved in recent years but remains approximately 4.6% and therefore by identifying dysplastic changes early it may be possible to prevent evolution to invasive malignancy that could benefit from oesophagectomy[75]. Different international management guidelines for BO are summarized in Table 2.

The prevalence of Barrett’s oesophagus is believed to be between 1.6% and 8%. Barrett’s oesophagus is a known precursor of oesophageal adenocarcinoma and the incidence of oesophageal cancer is rising. Although population screening is not yet indicated with the advent of new less invasive cytological screening for Barrett’s oesophagus this might change. Advances in endoscopic therapy mean that minimally invasive techniques are beginning to eliminate the role of high morbidity and mortality surgery.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Braden B, Kurokohchi K, Nathanson BH S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, Ang Y, Kang JY, Watson P, Trudgill N, Patel P, Kaye PV, Sanders S. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2014;63:7-42. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 858] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 846] [Article Influence: 76.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Desai TK, Krishnan K, Samala N, Singh J, Cluley J, Perla S, Howden CW. The incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in non-dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2012;61:970-976. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 388] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shaheen NJ, Crosby MA, Bozymski EM, Sandler RS. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastroenterology. 2000;119:333-338. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 551] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 512] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chang EY, Morris CD, Seltman AK, O’Rourke RW, Chan BK, Hunter JG, Jobe BA. The effect of antireflux surgery on esophageal carcinogenesis in patients with barrett esophagus: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2007;246:11-21. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 151] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Thomas T, Abrams KR, De Caestecker JS, Robinson RJ. Meta analysis: Cancer risk in Barrett’s oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1465-1477. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 112] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yousef F, Cardwell C, Cantwell MM, Galway K, Johnston BT, Murray L. The incidence of esophageal cancer and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:237-249. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 307] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sikkema M, de Jonge PJ, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ. Risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma and mortality in patients with Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:235-244; quiz e32. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 278] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wani S, Puli SR, Shaheen NJ, Westhoff B, Slehria S, Bansal A, Rastogi A, Sayana H, Sharma P. Esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus after endoscopic ablative therapy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:502-513. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 141] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5598-5606. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 657] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 724] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 10. | Pohl H, Pech O, Arash H, Stolte M, Manner H, May A, Kraywinkel K, Sonnenberg A, Ell C. Length of Barrett’s oesophagus and cancer risk: implications from a large sample of patients with early oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2016;65:196-201. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Spechler SJ. Barrett esophagus and risk of esophageal cancer: a clinical review. JAMA. 2013;310:627-636. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 175] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893-2917. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11128] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11733] [Article Influence: 838.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 13. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8406] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8928] [Article Influence: 686.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Mayer. “Esophageal cancer.”. New England J Med. 2003;349:2241-2252. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2115] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2172] [Article Influence: 98.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lepage C, Rachet B, Jooste V, Faivre J, Coleman MP. Continuing rapid increase in esophageal adenocarcinoma in England and Wales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2694-2699. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 194] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Pohl H, Welch HG. The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:142-146. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 956] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 939] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pennathur A, Farkas A, Krasinskas AM, Ferson PF, Gooding WE, Gibson MK, Schuchert MJ, Landreneau RJ, Luketich JD. Esophagectomy for T1 esophageal cancer: outcomes in 100 patients and implications for endoscopic therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:1048-154; discussion 1048-154;. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 201] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gilbert EW, Luna RA, Harrison VL, Hunter JG. Barrett’s esophagus: a review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:708-718. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shiota S, Singh S, Anshasi A, El-Serag HB. Prevalence of Barrett’s Esophagus in Asian Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1907-1918. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63:871-880. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1057] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1170] [Article Influence: 106.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Pohl H, Wrobel K, Bojarski C, Voderholzer W, Sonnenberg A, Rösch T, Baumgart DC. “Risk factors in the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma.”. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:200-207. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 110] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kubo A, Cook MB, Shaheen NJ, Vaughan TL, Whiteman DC, Murray L, Corley DA. Sex-specific associations between body mass index, waist circumference and the risk of Barrett’s oesophagus: a pooled analysis from the international BEACON consortium. Gut. 2013;62:1684-1691. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shariff MK, Bird-Lieberman EL, O’Donovan M, Abdullahi Z, Liu X, Blazeby J, Fitzgerald R. Randomized crossover study comparing efficacy of transnasal endoscopy with that of standard endoscopy to detect Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:954-961. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Saeian K, Staff DM, Vasilopoulos S, Townsend WF, Almagro UA, Komorowski RA, Choi H, Shaker R. Unsedated transnasal endoscopy accurately detects Barrett’s metaplasia and dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:472-478. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sharma P, Morales TG, Sampliner RE. Short segment Barrett’s esophagus--the need for standardization of the definition and of endoscopic criteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1033-1036. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Kim SL, Waring JP, Spechler SJ, Sampliner RE, Doos WG, Krol WF, Williford WO. Diagnostic inconsistencies in Barrett’s esophagus. Department of Veterans Affairs Gastroesophageal Reflux Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:945-949. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 123] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Dekel R, Wakelin DE, Wendel C, Green C, Sampliner RE, Garewal HS, Martinez P, Fass R. Progression or regression of Barrett’s esophagus--is it all in the eye of the beholder? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2612-2615. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, Inadomi JM, Shaheen NJ. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:e18-52; quiz e13. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 840] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 787] [Article Influence: 56.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kara MA, Peters FP, Rosmolen WD, Krishnadath KK, ten Kate FJ, Fockens P, Bergman JJ. High-resolution endoscopy plus chromoendoscopy or narrow-band imaging in Barrett’s esophagus: a prospective randomized crossover study. Endoscopy. 2005;37:929-936. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 242] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sami SS, Subramanian V, Butt WM, Bejkar G, Coleman J, Mannath J, Ragunath K. High definition versus standard definition white light endoscopy for detecting dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2015;28:742-749. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Canto MI, Setrakian S, Willis JE, Chak A, Petras RE, Sivak MV. Methylene blue staining of dysplastic and nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus: an in vivo and ex vivo study. Endoscopy. 2001;33:391-400. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 113] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Breyer HP, Silva De Barros SG, Maguilnik I, Edelweiss MI. Does methylene blue detect intestinal metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:505-509. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Horwhat JD, Maydonovitch CL, Ramos F, Colina R, Gaertner E, Lee H, Wong RK. A randomized comparison of methylene blue-directed biopsy versus conventional four-quadrant biopsy for the detection of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in patients with long-segment Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:546-554. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Guelrud M, Herrera I. Acetic acid improves identification of remnant islands of Barrett’s epithelium after endoscopic therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:512-515. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ngamruengphong S, Sharma VK, Das A. Diagnostic yield of methylene blue chromoendoscopy for detecting specialized intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1021-1028. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 105] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Guelrud M, Herrera I, Essenfeld H, Castro J. Enhanced magnification endoscopy: a new technique to identify specialized intestinal metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:559-565. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 195] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sharma P, Weston AP, Topalovski M, Cherian R, Bhattacharyya A, Sampliner RE. Magnification chromoendoscopy for the detection of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2003;52:24-27. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 214] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sharma P, Hawes RH, Bansal A, Gupta N, Curvers W, Rastogi A, Singh M, Hall M, Mathur SC, Wani SB. Standard endoscopy with random biopsies versus narrow band imaging targeted biopsies in Barrett’s oesophagus: a prospective, international, randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2013;62:15-21. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 240] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, Bergman JJ, Gossner L, Hoshihara Y, Jankowski JA, Junghard O, Lundell L, Tytgat GN. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett’s esophagus: the Prague C & amp; M criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1392-1399. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 731] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 694] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chang CY, Lee YC, Lee CT, Tu CH, Hwang JC, Chiang H, Tai CM, Chiang TH, Wu MS, Lin JT. The application of Prague C and M criteria in the diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus in an ethnic Chinese population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:13-20. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Vahabzadeh B, Seetharam AB, Cook MB, Wani S, Rastogi A, Bansal A, Early DS, Sharma P. Validation of the Prague C & amp; M criteria for the endoscopic grading of Barrett’s esophagus by gastroenterology trainees: a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:236-241. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Choe JW, Kim YC, Joo MK, Kim HJ, Lee BJ, Kim JH, Yeon JE, Park JJ, Kim JS, Byun KS. Application of the Prague C and M criteria for endoscopic description of columnar-lined esophagus in South Korea. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:357-361. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, Inadomi JM, Shaheen NJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1084-1091. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 377] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Riddell RH, Odze RD. Definition of Barrett’s esophagus: time for a rethink--is intestinal metaplasia dead? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2588-2594. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Ogiya K, Kawano T, Ito E, Nakajima Y, Kawada K, Nishikage T, Nagai K. Lower esophageal palisade vessels and the definition of Barrett’s esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:645-649. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wang KK, Sampliner RE; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. “Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus.”. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:788. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 850] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 770] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Ross-Innes CS, Debiram-Beecham I, O’Donovan M, Walker E, Varghese S, Lao-Sirieix P, Lovat L, Griffin M, Ragunath K, Haidry R. Evaluation of a minimally invasive cell sampling device coupled with assessment of trefoil factor 3 expression for diagnosing Barrett’s esophagus: a multi-center case-control study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001780. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 188] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Old OJ, Lloyd G, Almond M, Kendall C, Barr H, Shore A, Stone N. PTH-174 Non-endoscopic screening for barrett’s oesophagus: identifying neoplasia with infrared spectroscopy. Gut. 2015;64:A485-A485. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 49. | Liu X, Wong A, Kadri SR, Corovic A, O’Donovan M, Lao-Sirieix P, Lovat LB, Burnham RW, Fitzgerald RC. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease symptoms and demographic factors as a pre-screening tool for Barrett’s esophagus. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94163. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Desilets DJ, Nathanson BH, Navab F. Barrett’s esophagus in practice: gender and screening issues. J Men’s Health. 2014;11:177-182. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Levine DS, Blount PL, Rudolph RE, Reid BJ. Safety of a systematic endoscopic biopsy protocol in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1152-1157. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 150] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Fitzgerald RC, Saeed IT, Khoo D, Farthing MJ, Burnham WR. Rigorous surveillance protocol increases detection of curable cancers associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1892-1898. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Abrams JA, Kapel RC, Lindberg GM, Saboorian MH, Genta RM, Neugut AI, Lightdale CJ. Adherence to biopsy guidelines for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance in the community setting in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:736-42; quiz 710. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 250] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Peters FP, Curvers WL, Rosmolen WD, de Vries CE, Ten Kate FJ, Krishnadath KK, Fockens P, Bergman JJ. Surveillance history of endoscopically treated patients with early Barrett’s neoplasia: nonadherence to the Seattle biopsy protocol leads to sampling error. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:475-479. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 55. | Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Fléjou JF, Geboes K. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251-255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1463] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1500] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Boyer J, Laugier R, Chemali M, Arpurt JP, Boustière C, Canard JM, Dalbies PA, Gay G, Escourrou J, Napoléon B. French Society of Digestive Endoscopy SFED guideline: monitoring of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy. 2007;39:840-842. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Evans JA, Early DS, Fukami N, Ben-Menachem T, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Foley KQ. The role of endoscopy in Barrett’s esophagus and other premalignant conditions of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1087-1094. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 239] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 58. | BSG Guidelines: Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Oesophagus - An Update. 2015;. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 59. | NICE, Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s oesophagus with low grade dysplasia or no dysplasia, 2014. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/IPG496/chapter/1-Recommendations. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 60. | Duits LC, Phoa KN, Curvers WL, Ten Kate FJ, Meijer GA, Seldenrijk CA, Offerhaus GJ, Visser M, Meijer SL, Krishnadath KK. Barrett’s oesophagus patients with low-grade dysplasia can be accurately risk-stratified after histological review by an expert pathology panel. Gut. 2015;64:700-706. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 194] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Phoa KN, van Vilsteren FG, Weusten BL, Bisschops R, Schoon EJ, Ragunath K, Fullarton G, Di Pietro M, Ravi N, Visser M. Radiofrequency ablation vs endoscopic surveillance for patients with Barrett esophagus and low-grade dysplasia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1209-1217. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 445] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 426] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Conio M, Repici A, Cestari R, Blanchi S, Missale G, Lapertosa G, Calandri G, Filiberti R. Endoscopic mucosal resection for high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal carcinoma occurring in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:P253. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 63. | Ormsby AH, Petras RE, Henricks WH, Rice TW, Rybicki LA, Richter JE, Goldblum JR. Observer variation in the diagnosis of superficial oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2002;51:671-676. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 168] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Anders M, Bähr C, El-Masry MA, Marx AH, Koch M, Seewald S, Schachschal G, Adler A, Soehendra N, Izbicki J. Long-term recurrence of neoplasia and Barrett’s epithelium after complete endoscopic resection. Gut. 2014;63:1535-1543. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Orman ES, Li N, Shaheen NJ. Efficacy and durability of radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s Esophagus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1245-1255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 189] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Kim HP, Bulsiewicz WJ, Cotton CC, Dellon ES, Spacek MB, Chen X, Madanick RD, Pasricha S, Shaheen NJ. Focal endoscopic mucosal resection before radiofrequency ablation is equally effective and safe compared with radiofrequency ablation alone for the eradication of Barrett’s esophagus with advanced neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:733-739. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Phoa KN, Pouw RE, van Vilsteren FG, Sondermeijer CM, Ten Kate FJ, Visser M, Meijer SL, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Weusten BL, Schoon EJ. Remission of Barrett’s esophagus with early neoplasia 5 years after radiofrequency ablation with endoscopic resection: a Netherlands cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:96-104. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 183] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Haidry RJ, Dunn JM, Butt MA, Burnell MG, Gupta A, Green S, Miah H, Smart HL, Bhandari P, Smith LA. Radiofrequency ablation and endoscopic mucosal resection for dysplastic barrett’s esophagus and early esophageal adenocarcinoma: outcomes of the UK National Halo RFA Registry. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:87-95. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 160] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Gosain S, Mercer K, Twaddell WS, Uradomo L, Greenwald BD. Liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy in Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia: long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:260-265. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 98] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Ghorbani S, Tsai FC, Greenwald BD, Jang S, Dumot JA, McKinley MJ, Shaheen NJ, Habr F, Coyle WJ. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic spray cryotherapy for Barrett’s dysplasia: results of the National Cryospray Registry. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:241-247. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 71. | Kastelein F, Spaander MC, Steyerberg EW, Biermann K, Valkhoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Bruno MJ. Proton pump inhibitors reduce the risk of neoplastic progression in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:382-388. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Singh S, Garg SK, Singh PP, Iyer PG, El-Serag HB. Acid-suppressive medications and risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2014;63:1229-1237. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 182] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Rayner CJ, Gatenby P. Effect of antireflux surgery for Barrett’s esophagus: long-term results. Minerva Chir. 2016;71:180-191. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 74. | Morrow E, Bushyhead D, Wassenaar E, Hinojosa M, Loviscek M, Pellegrini C, Oelschlager B. The impact of laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:3279-3284. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Van Veer H, Moons J, Darling G, Lerut T, Coosemans W, Waddell T, De Leyn P, Nafteux P. Validation of a new approach for mortality risk assessment in oesophagectomy for cancer based on age- and gender-corrected body mass index. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;48:600-607. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Barrett’s Oesophagus - Diagnosis and Management. Available from: http://www.emedmd.com. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 77. | Barrett’s Oesophagus. Available from: http://www.dougsamuel.com.au/barretts/. [Cited in This Article: ] |