Published online Dec 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i45.10045

Peer-review started: July 11, 2016

First decision: September 5, 2016

Revised: September 20, 2016

Accepted: November 12, 2016

Article in press: November 13, 2016

Published online: December 7, 2016

To determine whether capsaicin infusion could influence heartburn perception and secondary peristalsis in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Secondary peristalsis was performed with slow and rapid mid-esophageal injections of air in 10 patients with GERD. In a first protocol, saline and capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce infusions were randomly performed, whereas 2 consecutive sessions of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce infusions were performed in a second protocol. Tested solutions including 5 mL of red pepper sauce diluted with 15 mL of saline and 20 mL of 0.9% saline were infused into the mid-esophagus via the manometric catheter at a rate of 10 mL/min with a randomized and double-blind fashion. During each study protocol, perception of heartburn, threshold volumes and peristaltic parameters for secondary peristalsis were analyzed and compared between different stimuli.

Infusion of capsaicin significantly increased heartburn perception in patients with GERD (P < 0.001), whereas repeated capsaicin infusion significantly reduced heartburn perception (P = 0.003). Acute capsaicin infusion decreased threshold volume of secondary peristalsis (P = 0.001) and increased its frequency (P = 0.01) during rapid air injection. The prevalence of GERD patients with successive secondary peristalsis during slow air injection significantly increased after capsaicin infusion (P = 0.001). Repeated capsaicin infusion increased threshold volume of secondary peristalsis (P = 0.002) and reduced the frequency of secondary peristalsis (P = 0.02) during rapid air injection.

Acute esophageal exposure to capsaicin enhances heartburn sensation and promotes secondary peristalsis in gastroesophageal reflux disease, but repetitive capsaicin infusion reverses these effects.

Core tip: This clinical significance of this study is that acute esophageal infusion of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce significantly enhances mechanosensitivity to distension-induced secondary peristalsis in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which might be beneficial in reflux patient with hypomotility. Conversely, repeated esophageal exposure to capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce may reduce the efficiency of esophageal secondary peristalsis. Repeated capsaicin infusion may therefore reduce the protection of the esophagus by hampering the clearing of residue substance or refluxate in the esophagus, which may in turn prolong acid clearance in patients with GERD.

- Citation: Yi CH, Lei WY, Hung JS, Liu TT, Chen CL, Pace F. Influence of capsaicin infusion on secondary peristalsis in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(45): 10045-10052

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i45/10045.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i45.10045

Secondary peristalsis is triggered by esophageal distension when food, liquid or air is retained in the esophagus after a failed primary peristaltic event or a reflux from the stomach[1]. It is important to maintain an empty esophagus by clearing the bulk of the volume of the refluxate after a reflux event[2]. In order to prevent prolonged acid contact time in the esophagus[3], secondary peristalsis helps normalize esophageal pH together with primary peristalsis and swallowed saliva[2]. It is suggested in human esophagus that both mucosal and muscular mechanoreceptors are involved in triggering secondary peristalsis which arises from a reflex arc mediated by a vagal afferent pathway[4,5].

Recent studies have demonstrated that patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) have considerably abnormal secondary peristaltic response rates when compared with aged matched controls[6]. By application of mid-esophageal injections of water and air, it was shown that GERD was characterized with defective triggering of secondary peristalsis[6]. We have recently studied secondary peristalsis in patients with GERD using mid-esophageal air stimulation with different speeds[7-9]. We notice that there is a substantial defect of activation of secondary peristalsis in a subgroup of GERD patients with significant esophageal dysmotility, indicating that increasing severity of failed primary peristalsis along with defective triggering of secondary peristalsis contributes to impaired esophageal clearance in patients with GERD[7].

Despite its effect of enhancing secondary peristalsis when acutely administered to the esophageal mucosa[10], we have recently demonstrated that repeated intra-esophageal infusion of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce indeed inhibited secondary peristalsis in healthy adults with reducing induction of heartburn symptoms[7]. The likelihood of secondary peristaltic response by abrupt air injection was increased by transient capsaicin infusion, but reduced by repeated capsaicin infusion. By characterizing esophageal desensitization as induced by repeated capsaicin infusion in modulation of secondary peristalsis in human esophagus, our recent work provides further insight in understanding the physiological basis of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) mediated chemosensitivity and mechanosensitivity in human esophagus[7].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that heartburn perception and physiological characteristics of secondary peristalsis can differently be influenced by acute or repetitive intra-esophageal infusion of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce in GERD patients.

In this prospective study, we enrolled consecutive patients with GERD who were previously diagnosed as having reflux disease by the presence of typical symptoms associated with positive endoscopy findings[11] or documented abnormal acid exposure on 24-hour pH monitoring. All patients had typical reflux symptoms lasting for more than 6 mo. We excluded subjects with the following clinical conditions: (1) esophageal strictures; (2) previous gastrointestinal surgery; (3) presence of systemic diseases that might interfere with esophageal motility; (4) chronic use of medications known to affect esophageal motility; and (5) intolerance and/or lack of cooperation with entire protocol. Prior to the study, all subjects did not use any medication that might affect gastrointestinal motility. This study was performed after approval by Research Ethics Committee of Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, Hualien, Taiwan and written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Stationary esophageal manometry was performed using a Koenigsberg 4-channel probe (Sandhill Scientific, Inc., Highlands Ranch, CO, United States). The catheter with 4.5 mm in diameter includes a circumferential solid-state pressure sensor at 5 cm and three unidirectional pressure sensors at 10, 20, and 25 cm from the tip. The infusion port is in the mid esophagus with its location between 15 and 20 cm from the tip. Each subject had the catheter inserted transnasally into the esophagus up to a depth of 60 cm. Then, we used stationary pull-through technique to withdraw the catheter until that the most distal sensor was located in the high-pressure zone of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Data of the entire study were then recorded and stored on the computer. Swallowing was detected by the most proximal channel of the catheter, which was located in the pharynx in order to distinguish primary and secondary peristalsis.

After an overnight fast, secondary peristalsis was recorded 10 min after esophageal infusion of saline and capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce, or 2 sessions of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce on two separate days. Tested solutions including 5 mL of red pepper sauce (Tabasco, McIlhenny Company, Avery Island, LA, United States), diluted with 15 mL of saline and 20 mL of 0.9% saline were infused into the mid-esophagus via the manometric catheter at a rate of 10 mL/min with a randomized and double-blind fashion. We wrapped the syringe in aluminum foil in order to mask characteristic colors of different infusions. Subjective symptoms including nausea, heartburn, stick and pain were evaluated with a visual analogue scale score (VAS) (0-100) shortly after each session of the infusion. The total amount of infused red pepper sauce suspension (5 mL of Tabasco) was equivalent to 0.84 mg of pure capsaicin[10,12].

Secondary peristalsis was generated by the air injection into the esophagus conducted first by a slow air injection with an infusion pump attached to the manometric catheter at a rate of 0.25 mL/s. We measured total amount of volume tested with the pump machine based on the rate and time for air injection to induce secondary peristalsis. Secondary peristalsis was then performed with rapid air injection, in which 1-mL volume was started and gradually increased by 1-mL increments until the activation of a secondary peristalsis or the volume of the injection reached 20 mL. The threshold volumes for air injections were measured as the minimal injection volume allowed for triggering a secondary peristaltic pressure wave[13]. Then, secondary peristaltic response was determined by ten times of 20 mL of air injections. We determined overall secondary peristaltic response with an interval of 20 s, during which each subject refrained from any swallow. Each subject was allowed to take a dry swallow to clear any residual air inside the esophagus and to avoid any swallow during next air injection at the end of 20 s.

Successful secondary peristalsis was recognized if the pressure wave was greater than 12 mmHg in the proximal esophagus and was greater than 25 mmHg in the distal esophagus with normal propagation[14]. The minimal latency of wave onset between two adjacent channels was 0.5 s. We analyzed the data in the same manner for both slow and rapid injections[14]. For measuring esophageal wave amplitude (mmHg) and duration (s), the recording sites were located 5 cm above upper margin of the LES.

We assessed the normality of all data by D’Agostino’s χ2 test. All data including amplitude, duration, VAS score, and threshold volumes of secondary peristalsis were present as mean ± SEM, and were compared by a paired t-test. Data for successful peristaltic response as induced by rapid air injection were analyzed and compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and were shown as median with interquartile range. Data for peristaltic wave amplitude and duration were compared for distal esophagus. Statistical significance was determined if P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 19 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., IL, United States).

We studied 17 reflux patients who met the enrollment criteria and entered the study between Dec 1, 2012 and Nov 31, 2013. Ten patients (4 females, mean age 42 years, range 20-64) completed the entire protocol with different session of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce infused to the esophagus without any complication. Of the patients with GERD, 8 patients with reflux esophagitis, LA grade A and 2 patients had normal endoscopy. The most frequent cause of exclusion from this study is intolerance to the protocol due to esophageal infusion with capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce.

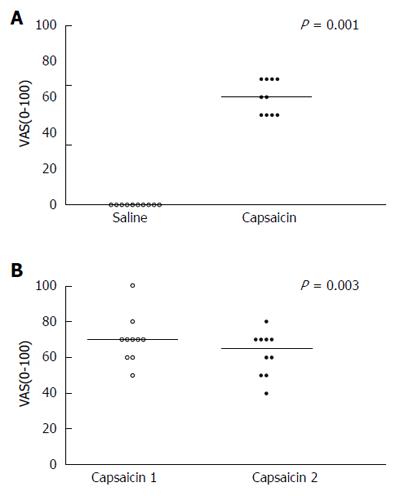

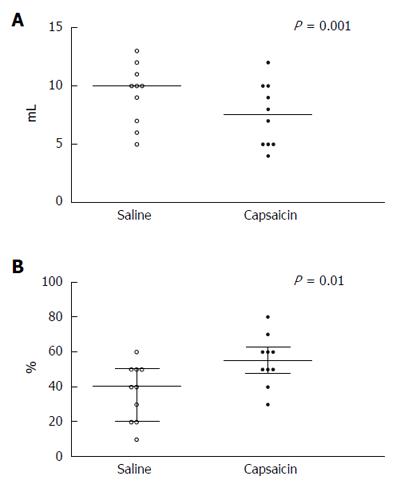

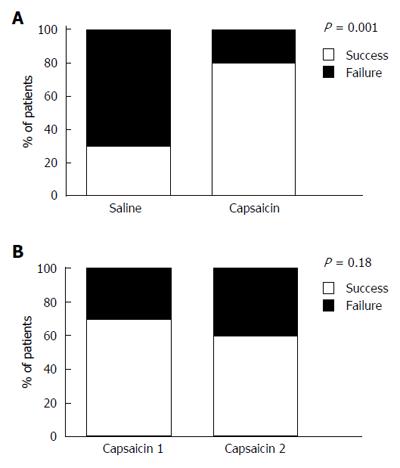

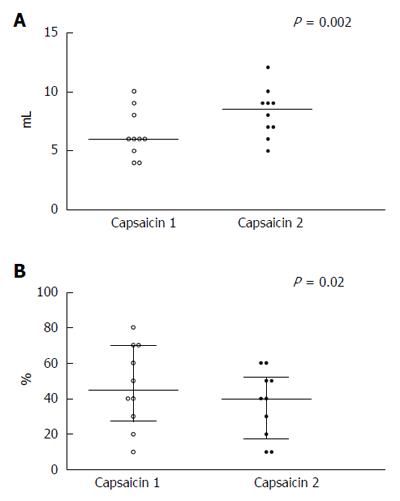

Infusion of capsaicin significantly increased the VAS score for heartburn symptom in patients with GERD when compared with saline infusion (P < 0.001) (Figure 1A). During 2 consecutive sessions of capsaicin infusion, the VAS score of heartburn symptom was significantly reduced after repeated infusion of capsaicin as compared with that after first capsaicin infusion (P = 0.003) (Figure 1B). When compared with saline infusion, infusion of capsaicin significantly reduced the threshold volume to activate secondary peristalsis during rapid air injection (P = 0.001) (Figure 2A), and a significant increase in the frequency of secondary peristalsis (P = 0.01) during rapid air injection (Figure 2B). Infusion of capsaicin increased the number of GERD patients with successive secondary peristalsis during slow air injection than saline infusion (P = 0.001) (Figure 3A), but the difference was not significant between first and second capsaicin infusions (P = 0.18) (Figure 3B). During 2 consecutive infusions of capsaicin infusions, there was a significant increase in threshold volume to generate secondary peristalsis after second infusion of capsaicin (P = 0.002) compared with that after first infusion of capsaicin during rapid air injection (Figure 4A). When compared with first infusion of capsaicin, second infusion of capsaicin significantly reduced the frequency of secondary peristalsis (P = 0.02) during rapid air injection (Figure 4B).

Infusion of capsaicin did not change pressure amplitude or duration when compared with saline infusion during slow and rapid air injections (Table 1). Furthermore, during 2 consecutive sessions of capsaicin infusions, no significant difference was found between 2 capsaicin infusions for any peristaltic parameters of secondary peristalsis during slow and rapid air injections (Table 1).

| Saline | Capsaicin | Capsaicin 1 | Capsaicin 2 | |

| Amplitude of contractions (mmHg) | ||||

| Slow distension | 82.9 (17.3) | 82.6 (20.2) | 95.9 (9.1) | 105.1 (11.1) |

| Rapid distension | 94.5 (11.5) | 104.8 (15.2) | 116.7 (22.0) | 121.8 (17.1) |

| Duration of contractions (s) | ||||

| Slow distension | 3.0 (0.3) | 3.5 (0.4) | 3.4 (0.5) | 3.5 (0.7) |

| Rapid distension | 3.24(0.4) | 4.0 (0.7) | 3.5(0.6) | 4.0 (0.7) |

This principal finding of this study is that acute esophageal infusion of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce significantly enhances heartburn perception and mechanosensitivity to distension-induced secondary peristalsis in patients with GERD, which might be beneficial in reflux patient with impaired esophageal motility[7]. However, secondary peristalsis is inhibited by repetitive esophageal infusion with capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce. Although this study supports the evidence that capsaicin sensitive afferents mediate heartburn symptom and secondary peristaltic thresholds, none of motility parameters of secondary peristalsis is influenced by acute or repeated esophageal infusion with capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce.

In this study, we found that heartburn symptoms in GERD patients were enhanced by rapid esophageal infusion of red pepper sauce, but was suppressed by repeated infusion of red pepper sauce. Our findings are in line with previous study which demonstrated the activation of heartburn symptom in non-GERD subjects with intra-esophageal instillation of capsaicin at a dose equivalent to 0.84 mg[10]. In addition, we have recently observed that repeated esophageal exposure to red pepper sauce reduced the intensity of heartburn symptom in healthy volunteers[15]. The findings are in agreement with an earlier work in GERD patients that also noticed an analgesic effect in perceiving heartburn after repeated stimulation with the capsaicin[16]. Together with these findings, it is conceivable that the perception of heartburn symptom is likely to be via TRPV1 receptor as established in our previous work[10]. Although sensitization of TRPV1 receptor is important for mediating perception of heartburn symptom[17,18], this receptor may also become desensitized after the continued presence of capsaicin[19]. Capsaicin is known to be an intrinsic primary afferent neurons excitant and a neurochemical substance that initially activates and later desensitizes afferent pathways[20]. It has been demonstrated in Pavlov’s esophageal fistula dog that the cephalic phase of gastric secretion can be modulated in condition when the pharynx was bypassed[21]. In this study, we found that repeated esophageal infusion of capsaicin selectively attenuated secondary peristalsis activated by rapid injection instead of slow air injection of the esophagus in GERD patients. Our findings are supported by the results of Lang et al[5] who showed in animal model that repeated application of capsaicin selectively inhibited the reflexes activated by rapid distension rather than slow distension of the esophagus. Therefore, current findings reemphasize the notion that the reflexes generated by rapid distension of the esophagus are modulated by chemically sensitive esophageal mechanoreceptors while those reflexes induced by slow distension are likely to be mediated by chemically insensitive mechanoreceptors. That notion is evident in patients with GERD.

The discrepancy in the amplitudes of secondary peristalsis after capsaicin infusion between healthy controls and GERD patients can be explained due to the fact that patients with GERD are more likely to have relatively poor motility in term of ineffective motility. In patients with abnormal primary peristalsis, abnormal secondary peristalsis has been observed[6]. It is suggested that the defect may occur in the efferent part of the motor pathway.

It is as yet not completely clear whether a desensitization of the esophagus can be induced by a repeated capsaicin infusion, although other studies have showed desensitization phenomenon in other human organs including the skin and nasal mucosa[22,23]. Acute jejunal infusion of capsaicin induced burning sensations and pain without affecting sensitivity to balloon distension[24,25], whereas other studies have shown that repeated administration of capsaicin is associated with reduced sensitivity to balloon distension in the intestine[26]. Conversely, there was no change in acid-induced esophageal mechanosensitivity to balloon distension after esophageal pretreatment with capsaicin[27]. It is conceivable that the effect on mechanosensitivity of capsaicin, regardless of mode for esophageal distension, on mechanosensitivity may be variable according to differences regarding types of stimuli and study designs. We have previously demonstrated a desensitization effect on distension-induced secondary peristalsis by repeated capsaicin infusion of the esophagus in healthy subjects[15]. In this study, we confirmed in a group of GERD patients that desensitization effect on secondary peristalsis can be accomplished by repeated esophageal capsaicin infusion.

It may be discussed whether repeated visceral exposure to capsaicin provides a complete esophageal desensitization[28], in particular in humans. It has been reported that the durations of desensitization can last from several hours to weeks after capsaicin exposure in human studies[22,29], and such a durable effect has been shown in upper gastrointestinal motility in healthy volunteers[30]. In this work, the duration of the desensitization effects of repeated capsaicin administrations was studied only in a limited time period, which may impact the physiological significance and mechanisms how capsaicin-induced analgesia generates in the esophagus. Indeed, after repeated infusion of capsaicin in this study, local esophageal capsaicin concentration may reach about 10 μmol/L, which may cause rapid degeneration of capsaicin-sensitive nerve endings[31]. It is probably that the desensitization effect of repeated capsaicin infusion is due to the temporary loss of capsaicin-sensitive afferents in the esophagus. This needs to be clarified by further longitudinal studies.

This study has some clinical implications. Current data support an earlier notion that esophageal mucosa is sensitive to capsaicin stimulation which induces heartburn symptom and which can be reduced by repeated exposure to capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce[32]. The fact that repeated esophageal exposure of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce decreases heartburn symptom appears to have potential therapeutic benefit for relieving heartburn symptom in patients with symptomatic GERD, although further work is needed to confirm its clinical utility. From the other hand, our study suggests that repeated esophageal exposure to capsaicin may inhibit secondary peristalsis and relevant reflex that may reduce the efficiency of esophageal transit and clearance as generated by secondary peristalsis[13]. By doing so, repeated capsaicin infusion may indeed reduce the protection of the esophagus by hampering the clearing of residue substance or refluxate in the esophagus, which may in turn prolong acid clearance in patients with GERD.

There are some limitations in this study with regard to the issue of desensitization capsaicin-induced of secondary peristalsis in patients with GERD. First, we did not apply the novel technique of high resolution manometry and impedance, which allows better characterization of secondary peristalsis, which may be missed by conventional manometry due to its inferior capability of depicting the peristaltic activity. Second, it is still unclear whether complete desensitization can be achieved by current dose of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce, although such dose has been successfully applied for studying heartburn and secondary peristalsis in human esophagus with a similar fashion to acid instillation[7,8,10]. The effect of desensitization is achievable only when the dose causes subjective symptoms with maximal magnitude; however, this is not ethically plausible for in vivo study in human esophagus. Third, there are possibly 2 subgroups of GERD including mild erosive reflux disease and those with non-erosive reflux disease; however, we enrolled those patients with typical symptoms as well as good response to acid suppression therapy to get a more homogeneous patient cohort. Finally, the number of studied subjects is small due to intolerability to the procedure, which may lead to type II error.

In summary, acute esophageal infusion with capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce appears to exacerbate heartburn symptom and promote the efficiency of secondary peristalsis in patients with GERD. However, these effects are likely to be reduced with repetitive esophageal exposure to capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce. Our study supports the hypothesis that capsaicin sensitive afferents are responsible for modulating esophageal symptom and distension-induced secondary peristalsis in patients suffering GERD symptoms.

A part of this study was presented as a presentation at the Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2014 in Chicago, Illinois and published as an abstract form in Gastroenterology (2014) 146 (5 Suppl. 1): S678.

Capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce improves esophageal secondary peristalsis in healthy adults.

The authors determined whether acute and repetitive capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce suspension could influence heartburn perception and secondary peristalsis in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Acute esophageal infusion with capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce appears to exacerbate heartburn symptom and promote the efficiency of secondary peristalsis in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, these effects are likely to be reduced with repetitive esophageal exposure to capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce.

The authors found that capsaicin sensitive afferents are responsible for modulating esophageal symptom and distension-induced secondary peristalsis in patients suffering GERD symptoms.

This was a qualitative study with an original approach to establishing the effects of capsaicin infusion in patients with GERD. The study was well designed and the results are clearly described.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Caboclo JL, Kusano M S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu WX

| 1. | Holloway RH. Esophageal body motor response to reflux events: secondary peristalsis. Am J Med. 2000;108 Suppl 4a:20S-26S. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Helm JF, Dodds WJ, Pelc LR, Palmer DW, Hogan WJ, Teeter BC. Effect of esophageal emptying and saliva on clearance of acid from the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:284-288. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 306] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Corazziari E, Pozzessere C, Dani S, Anzini F, Torsoli A. Intraluminal pH esophageal motility. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:275-277. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Kravitz JJ, Snape WJ, Cohen S. Effect of thoracic vagotomy and vagal stimulation on esophageal function. Am J Physiol. 1978;234:E359-E364. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Lang IM, Medda BK, Shaker R. Mechanisms of reflexes induced by esophageal distension. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1246-G1263. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Schoeman MN, Holloway RH. Integrity and characteristics of secondary oesophageal peristalsis in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1995;36:499-504. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 99] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen CL, Yi CH, Liu TT. Relevance of ineffective esophageal motility to secondary peristalsis in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:296-300. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen CL, Yi CH, Liu TT. Comparable effects of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce and hydrochloric acid on secondary peristalsis in humans. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1712-1716. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen CL, Yi CH, Liu TT, Orr WC. Effects of mosapride on secondary peristalsis in patients with ineffective esophageal motility. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1363-1370. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen CL, Liu TT, Yi CH, Orr WC. Effects of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce suspension on esophageal secondary peristalsis in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:1177-182, 1177-182. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172-180. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1518] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1521] [Article Influence: 60.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Lee KJ, Vos R, Tack J. Effects of capsaicin on the sensorimotor function of the proximal stomach in humans. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:415-425. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen CL, Szczesniak MM, Cook IJ. Oesophageal bolus transit and clearance by secondary peristalsis in normal individuals. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:1129-1135. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schoeman MN, Holloway RH. Stimulation and characteristics of secondary oesophageal peristalsis in normal subjects. Gut. 1994;35:152-158. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen CL, Yi CH, Liu TT. Effect of repeated esophageal infusion of capsaicin-contained red pepper sauce on secondary peristalsis in humans. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:S678. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Rodriguez-Stanley S, Collings KL, Robinson M, Owen W, Miner PB. The effects of capsaicin on reflux, gastric emptying and dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:129-134. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Holzer P. Capsaicin: cellular targets, mechanisms of action, and selectivity for thin sensory neurons. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:143-201. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Vanilloid (Capsaicin) receptors and mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:159-212. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Numazaki M, Tominaga T, Takeuchi K, Murayama N, Toyooka H, Tominaga M. Structural determinant of TRPV1 desensitization interacts with calmodulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8002-8006. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 252] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abdel Salam OM, Szolcsányi J, Mózsik G. The indomethacin-induced gastric mucosal damage in rats. Effect of gastric acid, acid inhibition, capsaicin-type agents and prostacyclin. J Physiol Paris. 1997;91:7-19. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pavlov IP, Thompson WH. The work of the digestive glands. London: C. Griffin 1910; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Stjärne P, Rinder J, Hedén-Blomquist E, Cardell LO, Lundberg J, Zetterström O, Anggård A. Capsaicin desensitization of the nasal mucosa reduces symptoms upon allergen challenge in patients with allergic rhinitis. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998;118:235-239. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wallengren J, Håkanson R. Effects of capsaicin, bradykinin and prostaglandin E2 in the human skin. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:111-117. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hammer J, Vogelsang H. Characterization of sensations induced by capsaicin in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:279-287. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schmidt B, Hammer J, Holzer P, Hammer HF. Chemical nociception in the jejunum induced by capsaicin. Gut. 2004;53:1109-1116. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Führer M, Hammer J. Effect of repeated, long term capsaicin ingestion on intestinal chemo- and mechanosensation in healthy volunteers. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:521-557, e7. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kindt S, Vos R, Blondeau K, Tack J. Influence of intra-oesophageal capsaicin instillation on heartburn induction and oesophageal sensitivity in man. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:1032-1e82. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Van Rijswijk JB, Boeke EL, Keizer JM, Mulder PG, Blom HM, Fokkens WJ. Intranasal capsaicin reduces nasal hyperreactivity in idiopathic rhinitis: a double-blind randomized application regimen study. Allergy. 2003;58:754-761. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 81] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Vanilloid receptor loss in rat sensory ganglia associated with long term desensitization to resiniferatoxin. Neurosci Lett. 1992;140:51-54. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gonzalez R, Dunkel R, Koletzko B, Schusdziarra V, Allescher HD. Effect of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce suspension on upper gastrointestinal motility in healthy volunteers. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1165-1171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Király E, Jancsó G, Hajós M. Possible morphological correlates of capsaicin desensitization. Brain Res. 1991;540:279-282. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yeoh KG, Ho KY, Guan R, Kang JY. How does chili cause upper gastrointestinal symptoms? A correlation study with esophageal mucosal sensitivity and esophageal motility. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21:87-90. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |