Published online Nov 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i43.9544

Peer-review started: August 10, 2016

First decision: August 29, 2016

Revised: September 9, 2016

Accepted: October 10, 2016

Article in press: October 10, 2016

Published online: November 21, 2016

Processing time: 103 Days and 12.3 Hours

To understand the influence of frailty on postoperative outcomes for laparoscopic and open colectomy.

Data were obtained from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (2005-2012) for patients undergoing colon resection [open colectomy (OC) and laparoscopic colectomy (LC)]. Patients were classified as non-frail (0 points), low frailty (1 point), moderate frailty (2 points), and severe frailty (≥ 3) using the Modified Frailty Index. 30-d mortality and complications were used as the primary end point and analyzed for the overall population. Complications were grouped into major and minor. Subset analysis was performed for patients undergoing colectomy (total colectomy, partial colectomy and sigmoid colectomy) and separately for patients undergoing rectal surgery (abdominoperineal resection, low anterior resection, and proctocolectomy). We analyzed the data using SAS Platform JMP Pro version 10.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

A total of 94811 patients were identified; the majority underwent OC (58.7%), were white (76.9%), and non-frail (44.8%). The median age was 61.3 years. Prolonged length of stay (LOS) occurred in 4.7%, and 30-d mortality was 2.28%. Patients undergoing OC were older (61.89 ± 15.31 vs 60.55 ± 14.93) and had a higher ASA score (48.3% ASA3 vs 57.7% ASA2 in the LC group) (P < 0.0001). Most patients were non-frail (42.5% OC vs 48% LC, P < 0.0001). Complications, prolonged LOS, and mortality were significantly more common in patients undergoing OC (P < 0.0001). OC had a higher risk of death and complications compared to LC for all frailty scores (non-frail: OR = 4.7, and OR = 4.67; mildly frail: OR = 2.51, and OR = 2.47; moderately frail: OR = 2.94, and OR = 2.02, severely frail: OR = 2.37, and OR = 2.34, P < 0.05) and an increase in absolute mortality with increasing frailty (non-frail 0.68% OC, mildly frail 1.39%, moderately frail 3.44%, and severely frail 5.83%, P < 0.0001).

LC is associated with improved outcomes. Although the odds of mortality are higher in non-frail, there is a progressive increase in mortality with increasing frailty.

Core tip: The safety of laparoscopic colectomy is well established; however to date little is understood regarding the influence of frailty on postoperative outcomes. The purpose of our study was to determine the safety of laparoscopic surgery for patient undergoing colonic resection through the frailty spectrum compared to open intervention. After analyzing a total of 94811 patients undergoing colectomy, and classifying them by their frailty scores. We found that laparoscopic surgery is superior to open surgery for patients undergoing colon resection regarding morbidity and mortality. Increases in frailty magnify differences between approaches.

- Citation: Mosquera C, Spaniolas K, Fitzgerald TL. Impact of frailty on approach to colonic resection: Laparoscopy vs open surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(43): 9544-9553

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i43/9544.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i43.9544

Laparoscopy has revolutionized abdominal surgery. Although there were concerns regarding oncologic safety in colorectal cancer (CRC), the COST, COLOR and CLASSIC trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of minimally invasive colectomy in patients with CRC[1-3]. A subsequent meta-analysis has also shown a decrease in the overall morbidity with similar mortality for laparoscopic colectomy[4]. For non-oncologic resections, similar results have been reported. Retrospective studies evaluating elective colectomy for diverticulosis and randomized trials such as the SIGMA have reported a significant reduction in postoperative morbidity with a minimally invasive approach[5,6]. Unfortunately, clinical trials in laparoscopic surgery have underrepresented the elderly and fail to account for frailty[7,8].

Most investigators define frailty as a decrease in physiological reserve of multiple organ systems with identifiable altered physical function beyond what is expected for normal aging[9,10]. The use of laparoscopic surgery in the medically unfit patient has been questioned due to concerns over prolonged operative times, increased the technical challenge, increased pneumoperitoneum-related physiologic demands, and patient positioning[11,12]. Indeed significant controversy exist regarding minimally invasive abdominal surgery in elderly patients as some studies have reported increased risk of complications[13], whereas, others have presented laparoscopic surgery to be a safe procedure even in the elderly[14,15]. Given this, it remains debated whether open or laparoscopic colorectal surgery is indicated in elderly patients with a poor performance status.

Little is understood regarding the impact of frailty on outcomes after colorectal surgery. It is unclear whether the increasingly technical and physiologic demands of laparoscopic surgery outweigh the benefits of a minimally invasive approach. The purpose of this study was to determine whether laparoscopic surgery remains superior to open intervention in the frail.

Data from American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality (ACS-NSQIP) Improvement Program Participant Use Files, which is a nationwide dataset containing data entered by trained clinical reviewers, for the period of 2005 to 2012 were used in this study. The dataset includes pre-operative risk factors, laboratory values, intraoperative data, and postoperative morbidity and mortality. However, these data have not been verified, and the ACS-NSQIP administration is not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived in this study. The Health Sciences Institutional Review Board of East Carolina University approved the study protocol.

This study focused on patients who underwent colorectal resection. We used current procedural terminology codes to identify patients who underwent open and laparoscopic colorectal resection from 2005 to 2012.

We used the Modified Frailty Index as described by Farhat et al[16]. This index was chosen because it is based upon the validated frailty index the Canadian Study of Health and Aging frailty index (CSHA-FI), and was adapted for ACS-NSQIP. We included the following factors to derive an 11- point score: functional status and endocrine, respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological disease. The patients were divided into four groups: non-frail (0), mildly frail (1), moderately frail (2), and severely frail (≥ 3).

End point: In this study, 30-d mortality and complications were used as the primary end point and analyzed for the overall population. Complications were grouped into major and minor, as previously reported[17]. Subset analysis was performed for patients undergoing colectomy (total colectomy, partial colectomy and sigmoid colectomy) and separately for patients undergoing rectal resection (abdominoperineal resection, low anterior resection, and proctocolectomy).

Data of continuous variables was reported as median and standard deviations and that of categorical data as frequency and proportions. Univariate analysis included Student’s t-test or Chi-square test, and Cox regression was utilized in a multivariate analysis that evaluated frailty groups independently. Multivariate analysis included patient demographics, type of procedure, and surgical approach. We analyzed the data using SAS Platform JMP Pro version 10.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

A total of 94811 patients undergoing colorectal resection met the inclusion criteria. A majority of these patients underwent an open procedure (58.7%). Most patients underwent partial colectomy (65.02%) followed by lower anterior resection (22.46%). The median age of the patients was 61.3 ± 15.17 years. The population was predominantly white (76.9%) with balanced gender distribution (52.13% females). The majority of patients had an American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) physical status classification system 2 (48.8%), followed by ASA 3 (43%), ASA 4 (4.8%), ASA 1 (3.1%), and ASA 5 (0.08%). The majority of patients were non-frail (44.8%), followed by mildly frail (37.5%), moderately frail (12.41%), and severely frail (5.20%). There were 23775 complications; of these, 57.9% were categorized as major. The median length of stay (LOS) was 8.32 ± 9.28 d, and prolonged LOS (> one standard deviation) occurred in 4.7% of the cases. The 30-d mortality was 2.28%.

Patients undergoing open intervention were slightly older (61.89 ± 15.31 years vs 60.55 ± 14.93 years, P < 0.0001). White was the most common race in both groups (76.9% in the open surgery group vs 79.38% in the laparoscopic group) while there were more African Americans in the open intervention group (10.46% vs 7.55%, P < 0.0001). Gender was similarly distributed between cohorts (P = 0.62).

There were significant differences in the ASA score between groups. In the open colectomy group, the majority of patients had an ASA 3 (48.3%), followed by ASA 2 (42.5%), ASA 4 (6.58%), ASA 1 (2.3%), and ASA 5 (0.13%). Comparatively, in the laparoscopic cohort, the majority of patients had an ASA 2 (57.7%), followed by ASA 3 (35.4%), ASA 4 (2.4%), ASA 1 (4.31%), and ASA 5 (0.01%) (P < 0.0001). The type of procedure was unevenly distributed between cohorts, with abdominal-perineal resections performed through an open approach in all patients and partial colectomies were commonly laparoscopic (open: 61.65% vs 69.82%). In the open colectomy group, the majority of patients were non-frail (42.5%), followed by mild frailty (37.44%), moderately frail (13.6%), and severely frail (6.48%). In the laparoscopic cohort, a majority of patients were also non-frail (48.16%), followed by mildly frail (37.69%), moderately frail (10.76%), and severely frail (3.4%) (P < 0.0001). Complications, prolonged LOS, and mortality were more common in patients undergoing an open intervention vs laparoscopic procedures (P < 0.0001) (Table 1).

| Characteristics, mean (± SD), (n) | Open colectomy n (%) | Lap colectomy n (%) | P value |

| Age 61.3 ± 15.17 | 61.89 ± 15.31 | 60.55 ± 14.93 | < 0.0001 |

| Race | |||

| AA (8778) | 5823 (10.46) | 2955 (7.55) | < 0.0001 |

| White (73879) | 42801 (76.90) | 31087 (79.38) | |

| Other (3808) | 2043 (3.67) | 1765 (4.51) | |

| Unknown (8346) | 4992 (8.97) | 3354 (8.57) | |

| Gender | 0.62 | ||

| Male (45383) | 26606 (47.08) | 18777 (47.96) | |

| Female (49428) | 29053 (52.50) | 20375 (52.04) | |

| ASA | |||

| Unknown (84) | 60 (0.11) | 24 (0.06) | < 0.0001 |

| 1 (2962) | 1276 (2.30) | 1686 (4.31) | |

| 2 (46287) | 23687 (42.50) | 22600 (57.72) | |

| 3 (40773) | 26898 (48.30) | 13875 (35.44) | |

| 4 (4627) | 3664 (6.58) | 963 (2.46) | |

| 5 (78) | 74 (0.13) | 4 (0.01) | |

| Frailty index | |||

| 0 (42507) | 23651 (42.49) | 18856 (48.16) | < 0.0001 |

| 1 (35596) | 20838 (37.44) | 14759 (37.69) | |

| 2 (11774) | 7562 (13.59) | 4212 (10.76) | |

| ≥ 3 (4934) | 3608 (6.48) | 1326 (3.39) | |

| Type of intervention | < 0.0001 | ||

| APR (524) | 524 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| LAR (21300) | 12056 (21.66) | 9244 (23.61) | |

| TPC (3760) | 2514 (4.52) | 1246 (3.18) | |

| Total colectomy (3210) | 2556 (4.59) | 654 (1.67) | |

| Partial colectomy (61646) | 34311 (61.65) | 27335 (69.82) | |

| Sigmoid colectomy (4371) | 3698 (6.64) | 673 (1.72) | |

| Complication | |||

| Yes (23755) | 17241 (30.98) | 6514 (16.64) | < 0.0001 |

| No (71056) | 38418 (69.02) | 32638 (83.36) | |

| Complication by severity | |||

| Minor (9,996) | 6884 (12.37) | 3112 (7.95) | < 0.0001 |

| Mayor (13759) | 10357 (18.61) | 3402 (8.69) | |

| No complication (71056) | 38418 (69.02) | 32638 (83.36) | |

| LOS, 8.32 ± 9.28 | 9.88 ± 10.37 | 5.89 ± 6.40 | < 0.0001 |

| Prolonged LOS | |||

| Yes (4472) | 3768 (10.42) | 704 (3.19) | < 0.0001 |

| No (53755) | 32397 (89.58) | 21358 (96.81) | |

| Mortality (30 d) | |||

| Yes (1766) | 1463 (2.63) | 303 (0.77) | < 0.0001 |

| No (93045) | 54196 (97.37) | 38849 (99.23) | |

| Total patients | 55659 (58.7) | 39152 (41.3) | 94811 |

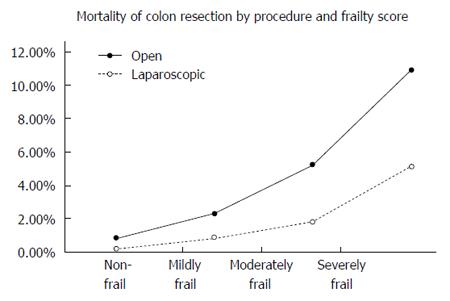

To clearly define the impact of frailty on surgical approach, univariate and multivariate analyses were performed for each frailty level; non-frail (0), mildly frail (1), moderately frail (2), and severely frail (> 3). The mortality rates were higher in the open colectomy cohort compared to the laparoscopic intervention. As frailty increases, the percentage mortality differences between open and laparoscopic interventions increased as well (non-frail: 0.86% open vs 0.17% laparoscopic, mildly frail: 2.26% vs 0.87%, moderately frail: 5.22% vs 1.78%, severely frail: 10.92% vs 5.13%) (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Mortality n (%) | P value | OR (95%CI), P value |

| Non frail (n = 42507) | |||

| Age | Yes: 65.22 ± 15.23 | < 0.0001 | 0.94 (0.95-1.05), < 0.0001 |

| No: 53.84 ± 15.09 | |||

| Race | |||

| AA | 20 (0.71) | 0.60 | - |

| White | 186 (0.55) | ||

| Other | 10 (0.54) | ||

| Unknown | 20 (0.47) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 122 (0.60) | 0.20 | 1.34 (1.03-1.75), 0.028 |

| Female | 114 (0.51) | Ref | |

| Type of intervention | < 0.0001 | ||

| APR | 1 (0.40) | 0.45 (0.02-2.04), 0.36 | |

| LAR | 31 (0.31) | 0.53 (0.35-0.77), 0.0008 | |

| TPC | 8 (0.32) | 0.81 (0.36-1.57), 0.56 | |

| Total colectomy | 15 (0.89) | 1.82 (1.02-3.04), 0.04 | |

| Partial colectomy | 162 (0.62) | Ref | |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 19 (1.16) | 1.18 (0.66-1.96), 0.54 | |

| Procedure | |||

| Open | 204 (0.86) | < 0.0001 | 4.65 (3.16-6.82), < 0.0001 |

| Lap | 32 (0.17) | Ref | |

| Characteristic mildly frail (n = 35596) | |||

| Age | Yes: 72.84 ± 12.25 | < 0.0001 | 0.94 (0.95-1.05), < 0.0001 |

| No: 65.75 ± 12.36 | |||

| Race | 0.59 | ||

| AA | 68 (1.64) | ||

| White | 453 (1.67) | ||

| Other | 20 (1.38) | ||

| Unknown | 57 (1.92) | ||

| Gender | 0.006 | ||

| Male | 302 (1.89) | 1.58 (1.33-1.88), < 0.0001 | |

| Female | 296 (1.51) | Ref | |

| Type of intervention | < 0.0001 | ||

| APR | 5 (2.55) | 1.14 (0.34-2.73), 0.79 | |

| LAR | 85 (1.05) | 0.68 (0.53-1.87), 0.0018 | |

| TPC | 14 (1.54) | 1.07 (0.58-1.81), 0.79 | |

| Total colectomy | 31 (3.27) | 1.94 (1.28-2.84), 0.00025 | |

| Partial colectomy | 405 (1.70) | Ref | |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 58 (3.48) | 1.77 (1.30-2.36), 0.0003 | |

| Procedure | |||

| Open | 470 (2.26) | < 0.0001 | 2.35 (1.92-2.91), < 0.0001 |

| Lap | 128 (0.87) | Ref | |

| Characteristic moderately frail (n = 11744) | |||

| Age | Yes: 74.7 ± 10.95 | < 0.0001 | 0.96 (0.11-17.47), < 0.0001 |

| No: 70.28 ± 11.2 | |||

| Race | |||

| AA | 49 (3.86) | 0.65 | - |

| White | 368 (3.96) | ||

| Other | 13 (3.53) | ||

| Unknown | 40 (4.76) | ||

| Gender | 0.34 | ||

| Male | 265 (4.15) | - | |

| Female | 205 (3.81) | ||

| Type of intervention | < 0.0001 | ||

| APR | 29 (3.77) | 0.89 (0.14-2.92), 0.87 | |

| LAR | 54 (2.39) | 0.68 (0.49-0.91), 0.018 | |

| TPC | 13 (5.94) | 1.70 (0.88-2.98), 0.10 | |

| Total colectomy | 28 (7.78) | 2.29 (1.48-3.40), 0.0003 | |

| Partial colectomy | 317 (3.86) | Ref | |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 56 (8.41) | 2.08 (1.50-2.83), < 0.001 | |

| Procedure | |||

| Open | 395 (5.22) | < 0.0001 | 2.70 (2.08-3.54), < 0.0001 |

| Lap | 75 (1.78) | Ref | |

| Characteristic: Severely frail (n = 4934) | |||

| Age | Yes: 75.92 ± 9.51 | < 0.0001 | 0.96 (0.15-13.07), < 0.0001 |

| No: 71.94 ± 10.02 | |||

| Race | |||

| AA | 50 (8.80) | 0.42 | - |

| White | 381 (9.61) | ||

| Other | 7 (5.79) | ||

| Unknown | 24 (8.54) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 281 (10.16) | 0.03 | 1.42 (1.16-1.75), 0.0006 |

| Female | 181 (8.35) | Ref | |

| Type of intervention | < 0.0001 | ||

| APR | 2 (8.33) | 0.75 (0.12-2.62), 0.69 | |

| LAR | 46 (5.67) | 0.63 (0.45-0.88), 0.0058 | |

| TPC | 10 (10.10) | 1.15 (0.55-2.15), 0.68 | |

| Total colectomy | 35 (16.67) | 2.07 (1.38-3.03), 0.0006 | |

| Partial colectomy | 299 (8.82) | Ref | |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 70 (17.59) | 1.94 (1.41-2.62), < 0.0004 | |

| Procedure | |||

| Open | 394 (10.92) | < 0.0001 | 2.13 (1.62-2.84), < 0.0001 |

| Lap | 68 (5.13) | Ref | |

The univariate analysis of the non-frail group revealed that age, male gender, type of intervention, and open procedure were associated with increased risk of mortality. The multivariate analysis revealed that age, male gender (OR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.03-1.75, P = 0.028), type of resection, and open colectomy (OR = 4.65, 95%CI: 3.16-6.82, P < 0.0001) remained associated with an increased risk of death. Similarly, for those with mild and severe frailty, age, male gender, type of procedure, and open colectomy (mildly frail OR = 2.35, 95%CI: 1.92–2.91, P < 0.0001) were associated with a higher mortality. In the case of moderately frail patients, factors like age, type of procedure, and open surgical intervention were associated with increased risk of death, on univariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, both factors remained statistically significant (Table 2).

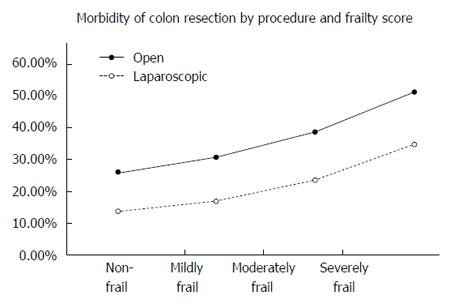

As above, univariate and multivariate analyses were performed for each frailty level. Univariate analysis showed that non-frail patients were more likely to have complications if they were older, African American, male, or underwent an open surgery (P < 0.0001). Multivariate analysis showed that age, male gender, type of procedure, and open colectomy (OR = 2.07, 95%CI: 1.97-2.18, P < 0.00001) remained significant (Table 3).

| Characteristic | Complication n (%) | P value | OR (95%CI), P value |

| Non frail (n = 42507) | |||

| Age | Yes: 53.74 ± 15.81 | < 0.0001 | 0.94 (0.95-1.05), < 0.001 |

| No: 53.94 ± 14.93 | |||

| Race | |||

| AA | 719 (25.63) | < 0.0001 | 1.29 (1.18-1.41), < 0.0001 |

| White | 6736 (20.07) | Ref | |

| Other | 362 (19.37) | 0.98 (0.87-1.10), 0.77 | |

| Unknown | 906 (21.24) | 1.06 (0.98-1.15), 0.11 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 4191 (20.73) | 0.30 | |

| Female | 4532 (20.33) | ||

| Type of intervention | < 0.0001 | ||

| APR | 55 (21.91) | 0.87 (0.64-1.18), 0.37 | |

| LAR | 1858 (18.32) | 0.97 (0.91-1.03), 0.34 | |

| TPC | 733 (28.95) | 1.71 (1.55-1.87), < 0.0001 | |

| Total colectomy | 536 (31.66) | 1.77 (1.59-1.98), < 0.0001 | |

| Partial colectomy | 18.58 (18.32) | Ref | |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 573 (34.90) | 1.88 (1.69-2.10), < 0.0001 | |

| Procedure | |||

| Open | 6143 (25.97) | < 0.0001 | 2.07 (1.97-2.18), < 0.0001 |

| Lap | 2580 (13.68) | Ref | |

| Characteristic, mildly frail (n = 35596) | |||

| Age | Yes: 65.81 ± 13.06 | < 0.0001 | 0.94 (0.94-0.95), < 0.0001 |

| No: 65.00 ± 12.17 | |||

| Race | |||

| AA | 1154 (27.90) | < 0.0001 | 1.15 (1.07-1.24), 0.0002 |

| White | 6637 (24.54) | Ref | |

| Other | 291 (20.07) | 0.81 (0.70-0.93), 0.0026 | |

| Unknown | 734 (25.78) | 1.06 (0.97-1.16), 0.18 | |

| Gender | 0.34 | ||

| Male | 4017 (25.09) | - | |

| Female | 4829 (24.66) | ||

| Type of intervention | < 0.0001 | ||

| APR | 61 (31.12) | 1.09 (0.80-1.48), 0.55 | |

| LAR | 1918 (23.72) | 1.01 (0.95-1.08), 0.58 | |

| TPC | 341 (37.47) | 1.78 (1.54-2.05), < 0.0001 | |

| Total colectomy | 370 (39.07) | 1.75 (1.53-2.01), < 0.0001 | |

| Partial colectomy | 5500 (23.12) | Ref | |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 656 (39.40) | 1.78 (1.60-1.98), < 0.0001 | |

| Procedure | |||

| Open | 6360 (30.52) | < 0.0001 | 2.05 (1.94-2.16), < 0.00001 |

| Lap | 2486 (16.85) | Ref | |

| Characteristic moderately frail (n = 11774) | |||

| Age | Yes: 70.480 ± 11.81 | < 0.0001 | 0.99 (0.99-1.00), < 0.0001 |

| No: 70.42 ± 10.82 | |||

| Race | |||

| AA | 472 (37.19) | 0.0013 | 1.20 (1.06-1.37), 0.003 |

| White | 2996 (32.21) | Ref | |

| Other | 118 (32.07) | 1.01 (0.80-1.26), 0.93 | |

| Unknown | 299 (35.81) | 1.12 (0.96-1.31), 0.13 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 2029 (31.75) | 0.0017 | 0.92 (00.85-1.00), 0.06 |

| Female | 1856 (34.48) | Ref | |

| Type of intervention | < 0.0001 | ||

| APR | 19 (35.85) | 0.97 (0.52-1.70), 0.92 | |

| LAR | 726 (32.12) | 1.05 (0.95-1.17), 0.28 | |

| TPC | 110 (50.23) | 2.10 (1.49-2.63), < 0.0001 | |

| Total colectomy | 182 (50.56) | 2.05 (1.65-2.55), < 0.0001 | |

| Partial colectomy | 2522 (30.70) | Ref | |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 326 (48.95) | 1.96 (1.66-2.31), < 0.0001 | |

| Procedure | |||

| Open | 2896 (38.38) | < 0.0001 | 1.89 (1.73-2.07), < 0.0001 |

| Lap | 989 (23.48) | Ref | |

| Characteristic severely frail (n = 4934) | |||

| Age | Yes: 71.89 ± 10.50 | 0.02 | 0.96 (0.040-0.17), < 0.0001 |

| No: 72.54 ± 9.57 | |||

| Race | |||

| AA | 295 (51.94) | 0.042 | 1.18 (0.98-1.42), 0.06 |

| White | 1822 (45.96) | Ref | |

| Other | 51 (42.15) | 0.90 (0.682-1.33), 0.61 | |

| Unknown | 133 (45.96) | 1.02 (0.79-1.32), 0.84 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1308 (42.27) | 0.31 | - |

| Female | 993 (45.82) | ||

| Type of intervention | < 0.0001 | ||

| APR | 12 (50) | 1.05 (0.46-2.38), 0.89 | |

| LAR | 350 (43.10) | 0.98 (0.84-1.15), 0.85 | |

| TPC | 53 (53.54) | 1.27 (0.85-1.91), 0.23 | |

| Total colectomy | 134 (63.81) | 1.96 (1.46-2.64), < 0.0001 | |

| Partial colectomy | 1499 (44.21) | Ref | |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 253 (63.57) | 1.94 (1.56-2.44), < 0.0001 | |

| Procedure | |||

| Open | 1842 (51.05) | < 0.0001 | 1.83 (1.60-2.09), < 0.0001 |

| Lap | 459 (3462) | Ref | |

The univariate analysis of mildly frail patients showed that age, race, type of procedure and surgical approach were associated with higher risk of complications, (P < 0.0001). On multivariate analysis, age, type of surgical intervention, and open procedure (OR = 2.05, 95%CI: 1.94-2.16, P < 0.0001) were the only factors that remained associated with increased risk of complications. For moderately frail patients, factors like age, race, gender, type of procedure, and surgical approach were associated with increased complications on univariate analysis (P < 0.05). On multivariate analysis, factors like age, female gender, African Americans compared to whites (OR = 1.19, 95%CI: 1.04-1.35, P = 0.006), type of surgical intervention, and open procedure (OR = 1.89, 95%CI: 1.73-2.07, P < 0.0001) conferred a significant risk of complications. Lastly, univariate analysis of the severely frail revealed that age, race, type of colon resection and open procedure had a higher risk of complications (P < 0.05). On multivariate analysis, age, type of surgical intervention, and open colectomy (OR = 1.83, 95%CI: 1.60-2.09, P < 0.0001) remained significant (Table 3).

Mortality and complication analyses were performed separately for rectal (low anterior resection, abdominal-perineal resection, and proctocolectomy) and colon procedures (total, partial and sigmoid colectomy). The results were similar to those for the overall population with an increase of mortality and complication rates as frailty increases. In both analyses, mortality and complications were found to be significantly higher in open interventions compared to the laparoscopic approach.

Laparoscopic colon resection is superior to open intervention for patients with both benign and maligning conditions. However, there are some concerns regarding safety in patients with significant medical comorbidities due to longer operative times, physiologic changes secondary to pneumoperitoneum, and required operative positioning[11,12]. To better understand the application of laparoscopic colorectal resection in the frail patients; we analyzed a large national database and found a significant increase in morbidity and mortality for open colectomy compared to laparoscopic colectomy. These findings were persistent regardless of the frailty status. As frailty increases, morbidity and mortality increase profoundly; however, the odds ratios were highest in the non-frail.

The association between frailty and postoperative outcomes has been previously evaluated. In the last couple of years, investigators have noted an increased risk of postoperative morbidity, prolonged length of stay, and mortality in frail patients undergoing surgical interventions[18,19]. Recent advances in understanding the complex concept of frailty may improve our capacity to evaluate better, risk stratify, and provide appropriated perioperative management for patients at risk[20]. Many questions regarding the impact of frailty in the surgical patients remain unanswered.

The impact of frailty on minimally invasive surgery has been evaluated in small retrospective case series. In patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Lasithiotakis et al[21] reported frail patients to have a higher incidence of complications and longer LOS when compared to the non-frail patients. Similarly, Revenig et al[22] evaluated 80 patients undergoing minimally invasive urologic, general surgery, and surgical oncology procedures and demonstrated an increased risk of postoperative complications in the frail population. However, to the best of our knowledge, the impact of frailty on minimally invasive colorectal resections compared to open surgery has not been reported.

In this series, we presented significantly increased mortality for open vs laparoscopic colectomy with increases in absolute mortality with frailty. As frailty increases, mortality also increases for all patients (Figure 1). Contrary to prior reports that laparoscopic surgery may be more dangerous in the medically unfit patients, our data suggest all patients derived significant benefits from this approach[12,23].

Similar results have been presented for the elderly and high-risk patients. In a meta-analysis evaluating the impact of age on colonic resection lower mortality and morbidity in geriatric patients for laparoscopic vs open surgery was noted. The authors recommended not to “overstate the choice of open intervention if minimally invasive expertise are available”[24]. Feroci in 2013 evaluated the impact of laparoscopic colonic surgery in low-risk and high-risk patients. High-risk was defined by the age, ASA score, and the presence of comorbidities. They reported a lower mortality in high-risk patients undergoing minimally invasive intervention compared to open approach[25].

Surgical approach has a significant impact on mortality following colon resection. In this series, patients undergoing open colectomy were more likely to die compared to patients undergoing laparoscopic intervention (2.63% vs 0.77%, P < 0.0001). Similar but not statistically significant results were presented at the completion of the COLOR and COST trials. In these randomized studies, patients undergoing open intervention had a higher risk of death (1 and 2% vs < 1 and 1%) when compared to those approached laparoscopically. Although mortality was doubled in both cases, the results failed to reach statistical significance. This may be due to a small number of patients and lack of statistical power[1,2]. More importantly, when comparing this study to the COST and COLOR trials, the ACS-NSQUIP patient population is less healthy with majority ASA 2-3 compared to ASA 1-2 in the randomized trial.

Patients undergoing laparoscopic colon resection have significantly fewer complications compared to those undergoing open intervention (16.6% vs 30.98%, P < 0.0001). As reported for mortality, increased morbidity with an open operation is present throughout frailty scores; however, differences in outcomes between laparoscopic and open surgical approach are magnified by increased frailty (Figure 2). Studies evaluating complications of open vs laparoscopic colon surgery have been reported in other complex population like the elderly. In this setting, the results are comparable to the ones obtained in our series. Li et al[26], in a systematic review and meta-analysis of patients older than 80 years undergoing colonic resection, demonstrated the benefits of laparoscopic surgery such as decreased LOS and morbidity. Similarly, Seishima et al[27] reported lowered risk of morbidity and mortality in the geriatric patient undergoing laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Based on these data, the author recommended an “Aggressive application of laparoscopic surgery in the elderly population”. This was also suggested by a randomized study comparing laparoscopic to open colonic surgery that included both young and elderly patients. The authors reported laparoscopy to improve postoperative outcomes more in the elderly than in the young patients, and advanced age was found to be associated with higher complications only in those patients who underwent open procedure[28].

While interpreting these data, clinicians must be mindful of the study limitations. First, ACS-NSQIP is a voluntary program, and the results may not be generalized to all hospitals. Second, the frailty score used in this study is a truncated retrospectively applied instrument that is similar to but not identical to the CSHA-FI. As a result, outcomes in this study may be dissimilar from those obtained from a validated prospectively applied measure of frailty. Lastly and more importantly, patient selection may play a significant role in outcome differences, as more complex patients (i.e., patients with a history of multiple abdominal surgeries) may be more likely to undergo open intervention this may skew our results for laparoscopic surgery.

In conclusion, laparoscopic surgery is superior to open surgery for patients undergoing colon resection regarding morbidity and mortality. The differences between both approaches are magnified by the increase in frailty. These data taken in context with the current surgical literature suggest that a laparoscopic approach to colorectal resection is preferred for all patients including the frail.

The role of laparoscopic colorectal surgery is controversial in frail patients. This study examines the benefits colorectal surgery across the spectrum of frailty.

In this study, the authors document that all patients benefit from a laparoscopic approach regardless of frailty.

These data can be applied to patients requiring laparoscopic colorectal surgery to help them understand risks and benefits.

This article has the aim to compare open colorectal surgery to laparoscopic colorectal surgery and analyse what effect frailty has on the outcome. This is a very important question today as most colorectal surgeons are dealing with the problem to decide if an old and frail patient should be operated or not.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kellokumpu IH, Stefánsson TB S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Veldkamp R, Kuhry E, Hop WC, Jeekel J, Kazemier G, Bonjer HJ, Haglind E, Påhlman L, Cuesta MA, Msika S. Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:477-484. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1691] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1638] [Article Influence: 86.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2050-2059. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2606] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2465] [Article Influence: 123.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM; MRC CLASICC trial group. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1718-1726. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2360] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2252] [Article Influence: 118.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abraham NS, Byrne CM, Young JM, Solomon MJ. Meta-analysis of non-randomized comparative studies of the short-term outcomes of laparoscopic resection for colorectal cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:508-516. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 95] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Klarenbeek BR, Bergamaschi R, Veenhof AA, van der Peet DL, van den Broek WT, de Lange ES, Bemelman WA, Heres P, Lacy AM, Cuesta MA. Laparoscopic versus open sigmoid resection for diverticular disease: follow-up assessment of the randomized control Sigma trial. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1121-1126. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kakarla VR, Nurkin SJ, Sharma S, Ruiz DE, Tiszenkel H. Elective laparoscopic versus open colectomy for diverticulosis: an analysis of ACS-NSQIP database. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1837-1842. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vignali A, Di Palo S, Tamburini A, Radaelli G, Orsenigo E, Staudacher C. Laparoscopic vs. open colectomies in octogenarians: a case-matched control study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2070-2075. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Feng B, Zheng MH, Mao ZH, Li JW, Lu AG, Wang ML, Hu WG, Dong F, Hu YY, Zang L. Clinical advantages of laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery in the elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2006;18:191-195. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, Syin D, Bandeen-Roche K, Patel P, Takenaga R, Devgan L, Holzmueller CG, Tian J. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:901-908. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1356] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1427] [Article Influence: 101.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Abellan van Kan G, Rolland Y, Houles M, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Soto M, Vellas B. The assessment of frailty in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26:275-286. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 237] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Grabowski JE, Talamini MA. Physiological effects of pneumoperitoneum. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1009-1016. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Henny CP, Hofland J. Laparoscopic surgery: pitfalls due to anesthesia, positioning, and pneumoperitoneum. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1163-1171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kang T, Kim HO, Kim H, Chun HK, Han WK, Jung KU. Age Over 80 is a Possible Risk Factor for Postoperative Morbidity After a Laparoscopic Resection of Colorectal Cancer. Ann Coloproctol. 2015;31:228-234. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li Y, Wang S, Gao S, Yang C, Yang W, Guo S. Laparoscopic colorectal resection versus open colorectal resection in octogenarians: a systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20:153-162. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Roscio F, Boni L, Clerici F, Frattini P, Cassinotti E, Scandroglio I. Is laparoscopic surgery really effective for the treatment of colon and rectal cancer in very elderly over 80 years old? A prospective multicentric case-control assessment. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4372-4382. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Farhat JS, Velanovich V, Falvo AJ, Horst HM, Swartz A, Patton JH, Rubinfeld IS. Are the frail destined to fail? Frailty index as predictor of surgical morbidity and mortality in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1526-1530; discussion 1530-1531. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 385] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Spaniolas K, Laycock WS, Adrales GL, Trus TL. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: advanced age is associated with minor but not major morbidity or mortality. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:1187-1192. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Robinson TN, Wu DS, Pointer L, Dunn CL, Cleveland JC, Moss M. Simple frailty score predicts postoperative complications across surgical specialties. Am J Surg. 2013;206:544-550. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 350] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hewitt J, Moug SJ, Middleton M, Chakrabarti M, Stechman MJ, McCarthy K. Prevalence of frailty and its association with mortality in general surgery. Am J Surg. 2015;209:254-259. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 128] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Amrock LG, Deiner S. The implication of frailty on preoperative risk assessment. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2014;27:330-335. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 83] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lasithiotakis K, Petrakis J, Venianaki M, Georgiades G, Koutsomanolis D, Andreou A, Zoras O, Chalkiadakis G. Frailty predicts outcome of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy in geriatric patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1144-1150. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Revenig LM, Canter DJ, Master VA, Maithel SK, Kooby DA, Pattaras JG, Tai C, Ogan K. A prospective study examining the association between preoperative frailty and postoperative complications in patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery. J Endourol. 2014;28:476-480. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bates AT, Divino C. Laparoscopic surgery in the elderly: a review of the literature. Aging Dis. 2015;6:149-155. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Antoniou SA, Antoniou GA, Koch OO, Pointner R, Granderath FA. Laparoscopic colorectal surgery confers lower mortality in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 66,483 patients. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:322-333. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Feroci F, Baraghini M, Lenzi E, Garzi A, Vannucchi A, Cantafio S, Scatizzi M. Laparoscopic surgery improves postoperative outcomes in high-risk patients with colorectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1130-1137. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Li JC, Leung KL, Ng SS, Liu SY, Lee JF, Hon SS. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open resection of right-sided colonic cancer--a prospective randomized controlled trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:95-102. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Seishima R, Okabayashi K, Hasegawa H, Tsuruta M, Shigeta K, Matsui S, Yamada T, Kitagawa Y. Is laparoscopic colorectal surgery beneficial for elderly patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:756-765. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Frasson M, Braga M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Di Carlo V. Benefits of laparoscopic colorectal resection are more pronounced in elderly patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:296-300. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 169] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |