Published online Feb 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2563

Peer-review started: August 26, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: October 28, 2014

Accepted: November 19, 2014

Article in press: November 19, 2014

Published online: February 28, 2015

Processing time: 187 Days and 4.6 Hours

The rectal tonsil, a reactive proliferation of lymphoid tissue located in the rectum, is rare. Histologically, benign lymphoid hyperplasia of the rectum is usually characterized by large lymphoid follicles with active germinal centers and a narrow surrounding mantle zone and marginal zone. This lesion is benign, but must be differentiated from the polypoid type of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas. In the current paper, we present a case of rectal tonsil in a 59-year-old woman. We describe the endoscopic ultrasound imaging findings with literature review.

Core tip: The rectal tonsil, a reactive proliferation of lymphoid tissue located in the rectum, is rare. Histologically, benign lymphoid hyperplasia of the rectum is usually characterized by large lymphoid follicles with active germinal centers and a narrow surrounding mantle zone and marginal zone. This lesion is benign, but must be differentiated from the polypoid type of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas.

- Citation: Hong JB, Kim HW, Kang DH, Choi CW, Park SB, Kim DJ, Ji BH, Koh KW. Rectal tonsil: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(8): 2563-2567

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i8/2563.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2563

Prominent and localized lymphoid hyperplasia in the rectum is also known as benign lymphoma, rectal lymphoid polyp or rectal tonsil[1-4]. Rectal tonsil is a rare colorectal disease and its etiology is unknown.

Histologically, it shows a dense lymphoid infiltrate in the submucosa and/or lamina propria at low power which mimics lymphoma. It can be differentiated from a malignant lymphoma by the proliferation of normal lymphoid tissue, which has a prominent follicular pattern and a clearly defined germinal center that varies in size; often being strikingly enlarged with a narrow surrounding mantle zone. The prevalence of the prominent and localized lymphoid hyperplasia is unevenly distributed and increases from the right to the left colon, being most frequent in the rectum, particularly just above the dentate line. It is noted to be more frequent in young children and adolescents.

In the current paper, we describe endoscopic, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), histomorphological and immunophenotypic findings of cases of benign lymphoid hyperplasia of the rectum.

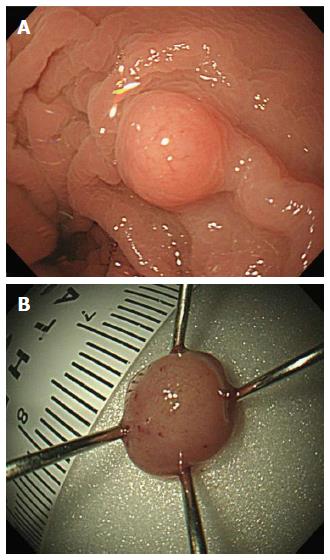

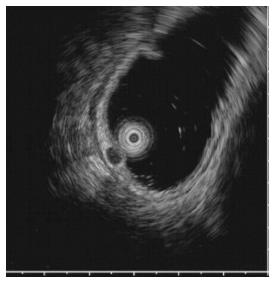

A 59-year-old woman was admitted to our department with suspicious tuberculous colitis. Her past medical and family histories were unremarkable. On admission, physical examination was also unremarkable. Blood test results showed no evidence of leukocytosis or anemia, and liver function tests were within the normal range. The levels of tumor markers were within the normal reference range, as follows: carcinoembryonic antigen, 1.83 ng/mL (normal < 5 ng/mL); and cancer antigen 19-9, 8.39 U/mL (normal < 37 U/mL). Tuberculin test was negative and a chest X-ray showed no active lung lesion but Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) interferon test in blood was positive. A chest X-ray showed normal finding. Colonoscopy showed an ulcerous lesion in the ascending colon and cecum. The ileocecal valve was totally destroyed with ulcer and pseudopolyp formation. Furthermore, a hard, solitary sessile mass (about 5 mm) was identified at 10 cm from the anal verge (Figure 1). EUS showed a 5-mm homogeneous hypoechoic mass located in the submucosa without definite lymph node enlargement (Figure 2). These findings suggested tuberculous colitis in the cecum or carcinoid tumor in the rectum.

Abdominal computed tomography demonstrated no evidence of metastatic regional lymph nodes. The pathological examination of all endoscopic forceps biopsies showed chronic inflammation. Acid-fast stains were negative. Polymerase chain reaction was negative for M. tuberculosis.

With endoscopic and EUS findings, rectal carcinoid was initially suspected and we performed cap-endoscopic mucosal resection (C-EMR) (Figure 3A). After a crescent-shaped snare was looped into the lip of a transparent cap attached to the distal end of the endoscope, the lesion was suctioned and the submucosal layer was resected with the snare using a cutting current.

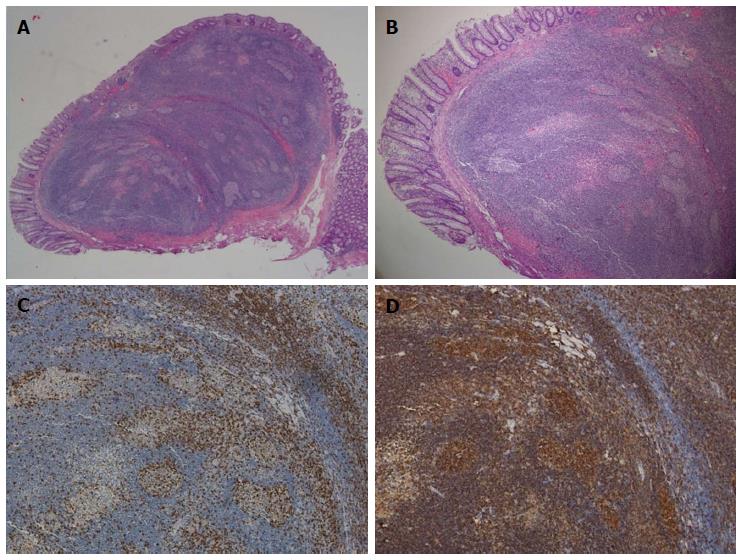

We showed a dense lymphoid infiltrate mainly located in the submucosa and extended to the mucosa. It appeared as a disc of yellow-white mucosal tissue, measuring 0.8 cm × 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm. The lesion was characterized by follicles with well-formed reactive germinal centers of various sizes; there were abundant macrophages inside the germinal follicles (Figure 3B). Immunohistology demonstrated typical lymphoid follicles and suggested follicular type of proliferation with positive B cells markers for CD20+ (B cells) (Figure 3C), and positive intraepithelial lymphocytes for CD3+ (T cells) (Figure 3D). There was no evidence of monoclonal expansion of B cells. These studies confirmed reactive lymphoid proliferation, and excluded lymphoma and other forms of non-neoplastic lymphoid proliferation with intact follicles, such as lymphoid follicular proctitis and lymphoid polyps of the rectum.

The patient received tuberculostatic therapy with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for 6 mo. The most recent endoscopy, 3 mo after tuberculostatic therapy and C-EMR, showed grossly normal healed mucosa in the cecum, ascending colon and rectum.

Rectal tonsil was initially described in veterinary pathology as a structure composed of dense lymphoid tissue[2]. Although it is not widely recognized as a distinct entity in humans, rectal tonsil is a useful designation for the prominent lymphoid tissue that can be observed at this location[5,6]. Recently, rectal tonsil was described as a prominent and localized lymphoid hyperplasia in the rectum[7].

Upon endoscopy, rectal tonsil mostly appears as a sessile lesion, varying in size (usually < 40 mm), but can appear as a polypoid mass. EUS is an accurate modality for the identification of benign and malignant rectal carcinoid and other submucosal tumors, as well as extraintestinal compressive lesions[8]. Conventional endoscopic and EUS findings of carcinoid tumors are similar to those of rectal tonsil, therefore, differential diagnosis between rectal tonsil and carcinoid tumors is difficult. Small carcinoid tumors, measuring < 1 cm in diameter, are hypoechoic or isoechoic nodules located in the mucosa and submucosa, and rectal tonsil appears in various sizes located in the submucosa and/or lamina propria. However, rectal tonsil is usually less yellow-white in color than carcinoid tumor. Moreover, rectal bleeding is commonly seen in rectal tonsil, whereas carcinoid tumor is asymptomatic.

Since 2006, > 18 cases of rectal tonsil have been reported in the English-language literature. The clinicopathological features of the 18 patients are summarized in Table 1[5,9-13]. There were six male and 12 female patients aged 1-71 years. Colonoscopy was conducted for screening in nine cases, evaluation of rectal bleeding/hematochezia in seven, evaluation of chronic constipation in one, and further investigation of abnormal rectal examination in one. Rectal bleeding and abnormal lesions were all found via routine screening. Endoscopic descriptions, available in all cases, reported a raised, polypoid lesion in 11 cases, a sessile polyp in three, a nodule in two, and multiple polyps and masses in one case each. Most rectal tonsils are usually < 6 mm, except for three cases (12, 30 and 40 mm). Histologically, there was lymphoid proliferation involving the submucosa and/or mucosa in all cases. Lymphoid follicles could be identified in all cases. EUS was not performed in all patients.

| Ref. | Country | Case | Sex(M/F) | Mean age (yr) | Mean size (mm) | Most common endoscopic appearance (n) | Most common clinical symptom (n) | Histological involvement |

| Kojima et al[9], 2005 | Japan | 3 | (0/3) | 59 (46-66) | 5.5 (5-6) | Polypoid (1) Multiple polypoid (1) Sessile (2) | Rectal bleeding (1) Screening (2) | Mucosa, submucosa |

| Kojima et al[10], 2007 | Japan | 2 | (0/2) | 61 (50-71) | 5.5 (5-6) | Sessile polyp (2) | Screening | Mucosa, submucosa |

| Farris et al[5], 2008 | United States | 11 | (6/5) | 49 (1-62) | 6 (3-12) | Polypoid (8) Nodule (2) Sessile polyp (1) | Screening (rectal bleeding, abdominal pain) | Submucosa, lamina propria |

| Eire et al[11], 2011 | Spain | 1 | (0/1) | 4 | 30 | Polypoid | Rectal bleeding | Submucosa, lamina propria |

| Homan et al[12], 2012 | Slovenia | 1 | (0/1) | 6 | 5 | Sessile polyp | Rectal bleeding | Superficial mucosa |

| Grube-Pagola et al[13], 2012 | Mexico | 1 | (1/0) | 58 | 40 | Sessile polyp | Rectal bleeding | Mucosa, submucosa, lamina propria |

Histologically, rectal tonsil shows a dense nodular lymphoid infiltrate in the lamina propria and submucosa. When the reactive lymphoid infiltrate has an abundance of atypical lymphoid cells, it can be difficult to distinguish rectal tonsil from lymphoma. Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type accounts for the majority of rectal lymphoma[14]. Extranodal MALT lymphoma is usually based on morphology and immunophenotypic inferences of malignancy and clonality such as anomalous antigen expression and/or immunoglobulin light chain restriction. Occasionally, MALT-type lymphoma shows a follicular growth pattern resulting from prominent follicular colonization. The tumor cells of MALT-type lymphoma are small-to-medium lymphocytes showing a moderate amount of clear cytoplasm, indented or round nuclei, and absent or small nucleoli (centrocyte-like cells)[15]. However, immunohistochemistry has demonstrated that proliferating cells are sIgD+, sIgM+ and CD5-, CD23+/-, and CD43-[16]. Benign lymphoid hyperplasia of the rectum is usually characterized by large lymphoid follicles with active germinal centers and a narrow surrounding mantle zone and marginal zone. It usually bears little resemblance to any type as described by Schmid et al[17].

In conclusion, rectal tonsil is a rare disease with variable features of age, sex, size, formation and location. Conventional endoscopic and EUS findings of carcinoid tumors are similar to those of rectal tonsil. However, rectal tonsil is usually less yellow-white in color than carcinoid tumor upon endoscopy. Moreover, rectal bleeding is frequently seen in rectal tonsil, while most carcinoid tumors are asymptomatic. The histological features suggest a benign process and the frequent occurrence of mitotic figures in well-developed mature lymphocytes. Also, there is no cytogenetic, molecular genetic or phenotypic evidence of malignancy.

In our case, endoscopy revealed a yellow-white, hard subepithelial lesion in the posterior rectum at 10 cm from the anal verge, combined with tuberculous colitis in the cecum. EUS showed a smooth, well-demarcated, homogeneous, hypoechoic solid lesion in the submucosa and lamina propria. The lesion was difficult to distinguish from carcinoid tumor with gross endoscopic and EUS findings. To avoid misdiagnosis and overtreatment, complete endoscopic resection, histopathological examination and immunophenotypic studies are recommended.

It was discovered during routine surveillance colonoscopy, and the patient had no symptoms.

The colonoscopic findings were highly suspicious of tuberculous colitis and carcinoid tumor.

Rectal tonsil is benign, but must be differentiated from the polypoid type of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas.

The laboratory findings were unremarkable.

The colonoscopic findings were highly suspicious of tuberculous colitis or carcinoid tumor.

In their case, a reactive lymphoid proliferation was confirmed and lymphoma and other forms of non-neoplastic lymphoid proliferation with intact follicles such as lymphoid follicular proctitis and lymphoid polyps of the rectum were excluded.

Treatment was not required for rectal tonsil per se but tuberculostatic therapy was commenced for colonic tuberculosis.

Cap-endoscopic mucosal resection procedure: After a crescent-shaped snare was looped into the lip of a transparent cap attached to the distal end of the endoscope, the lesion was suctioned and the submucosal layer was resected with the snare using a cutting current, and a safe margin was ensured.

In the present case, a lesion that was strongly suspicious of rectal carcinoid was identified via surveillance colonoscopy but it was found to be rectal tonsil. It is important to distinguish rectal tonsil from MALT lymphoma and other benign lymphoid hyperplasia and the differential diagnosis can be made with immunohistochemistry.

It this manuscript, the authors described a simple but rare case of “rectal tonsil”. The case is interesting and not very frequent and it is well represented in terms of iconography, with very good endoscopic, ultrasonographic and histological images.

P- Reviewer: Riss S, Santos-Antunes J S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Ranchod M, Lewin KJ, Dorfman RF. Lymphoid hyperplasia of the gastrointestinal tract. A study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1978;2:383-400. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kealy WF. Colonic lymphoid-glandular complex (microbursa): nature and morphology. J Clin Pathol. 1976;29:241-244. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Cornes JS, Wallace MH, Morson BC. Benign lymphomas of the rectum and anal canal: a study of 100 cases. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1961;82:371-382. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kraehenbuhl JP, Neutra MR. Epithelial M cells: differentiation and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:301-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Farris AB, Lauwers GY, Ferry JA, Zukerberg LR. The rectal tonsil: a reactive lymphoid proliferation that may mimic lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1075-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ogra PL. Mucosal immunity: some historical perspective on host-pathogen interactions and implications for mucosal vaccines. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;81:23-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ashley PF, Smith C. Lymphoid polyps (benign lymphoma) of the rectum and anus. Del Med J. 1959;31:310-312. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ishii N, Horiki N, Itoh T, Maruyama M, Matsuda M, Setoyama T, Suzuki S, Uchida S, Uemura M, Iizuka Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection and preoperative assessment with endoscopic ultrasonography for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1413-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kojima M, Itoh H, Motegi A, Sakata N, Masawa N. Localized lymphoid hyperplasia of the rectum resembling polypoid mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: a report of three cases. Pathol Res Pract. 2005;201:757-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kojima M, Iijima M, Shimizu K, Hoshi K. Localized lymphoid hyperplasia of the rectum representing progressive transformation of the germinal center. A report of two cases. APMIS. 2007;115:1432-1436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Eire PF, Victoria RF, Castañón AI, Arias MP, Carril AL, Burriel JI. The rectal tonsil in children: a reactive lymphoid proliferation that may mimic a lymphoma. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2011;30:282-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Homan M, Volavšek M. Rectal tonsil. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Grube-Pagola P, Canales-Kay A, Meixueiro-Daza A, Remes-Troche JM. Rectal tonsil associated with Epstein-Barr virus. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E388-E389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shepherd NA, Hall PA, Coates PJ, Levison DA. Primary malignant lymphoma of the colon and rectum. A histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 45 cases with clinicopathological correlations. Histopathology. 1988;12:235-252. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Isaacson PG, Wotherspoon AC, Diss T, Pan LX. Follicular colonization in B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:819-828. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Lai R, Weiss LM, Chang KL, Arber DA. Frequency of CD43 expression in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. A survey of 742 cases and further characterization of rare CD43+ follicular lymphomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111:488-494. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Schmid C, Vazquez JJ, Diss TC, Isaacson PG. Primary B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma presenting as a solitary colorectal polyp. Histopathology. 1994;24:357-362. [PubMed] |