Published online Feb 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i5.1588

Peer-review started: January 14, 2014

First decision: March 4, 2014

Revised: March 31, 2014

Accepted: May 19, 2014

Article in press: May 23, 2014

Published online: February 7, 2015

Processing time: 391 Days and 21.8 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy (LPD) using a reverse-“V” approach with four ports.

METHODS: This is a retrospective study of selected patients who underwent LPD at our center between April 2011 and April 2012. The following data were collected and reviewed: patient characteristics, tumor histology, surgical outcome, resection margins, morbidity, and mortality. All patients were thoroughly evaluated preoperatively by complete hematologic investigations, triple-phase helical computed tomography, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and biopsy of ampullary lesions (when present). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography was performed for doubtful cases of lower common bile duct lesions.

RESULTS: There was no perioperative mortality. LPD was performed with tumor-free margins in all patients, including patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (n = 6), ampullary carcinoma (n = 6), intra-ductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (n = 2), pancreatic cystadenocarcinoma (n = 2), pancreatic head adenocarcinoma (n = 3), and bile duct cancer (n = 2). The mean patient age was 65 years (range, 42-75 years). The median blood loss was 240 mL, and the mean operative time was 368 min.

CONCLUSION: LPD using a reverse-“V” approach can be performed safely and yields good results in elective patients. Our preliminary experience showed that LDP can be performed via a reverse-“V” approach. This approach can be used to treat localized malignant lesions irrespective of histopathology.

Core tip: Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy via reverse -“V” approach can be performed with safety and obtain good results in elective patients. The preliminary experience showed a good prospect via reverse-“V” approach for LDP. Localized malignant lesions and irrespective of histopathology may be particularly amenable to this approach.

-

Citation: Liu Z, Yu MC, Zhao R, Liu YF, Zeng JP, Wang XQ, Tan JW. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy

via a reverse-''V'' approach with four ports: Initial experience and perioperative outcomes. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(5): 1588-1594 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i5/1588.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i5.1588

Laparoscopic pancreatioduodenectomy (LPD) was first reported in 1994[1], and the procedure is not currently a well-accepted treatment approach. The concerns regarding the use of LPD stem from the long operative time, the need of perfect operational skills, and the lack of obvious advantages[2-6]. In our institution, most abdominal operations could be performed using a laparoscopic approach eight years ago. The eligible surgeries include laparoscopic liver resection, pancreatectomy, gastrectomy, and other surgeries. LPD is not commonly performed because the procedure is associated with high mortality and morbidity[7].

We have accumulated substantial experience in laparoscopic surgery and developed a modified Whipple procedure, namely, a reverse-“V” approach, to optimize the laparoscopic surgery for selected oncology patients. This report focuses on a laparoscopic surgical procedure completed with the reverse-“V” approach using four ports.

Between April 2011 and April 2012, 40 pancreaticoduodenectomies were performed at our institution. Of these, 21 (52.5%) patients were scheduled for laparoscopic resection. Similar to a study by Corcione et al[5], all patients who were included in the series met the following inclusion criteria: American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade I to III and the presence of pancreatic head tumors restricted to the second part of the duodenum, well-differentiated or moderate grade ampullary tumors restricted to the second part of the duodenum, or bile duct tumors. The exclusion criteria for LPD were tumor invasion into the portal vein (PV) or the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) on radiographic imaging for which venous resection could be necessary. The following patient data were reviewed: demographic data, preoperative evaluation, surgical procedure, perioperative data, morbidity, and pathology. All patients were thoroughly evaluated preoperatively by complete hematologic investigations, triple-phase helical computed tomography (CT), upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and biopsy of ampullary lesions (when present).

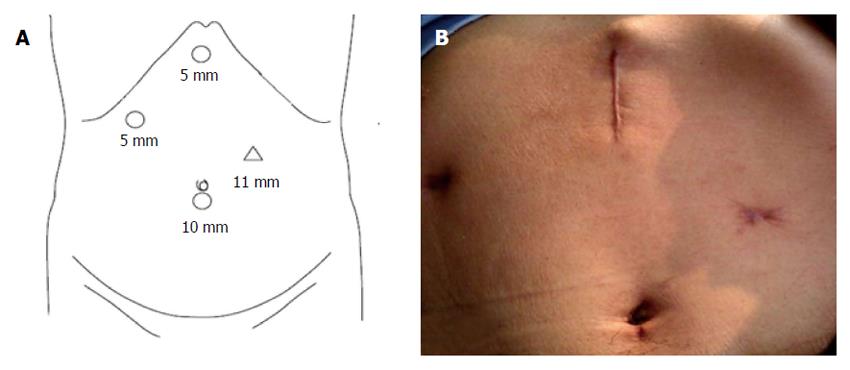

The procedure was performed under general anesthesia with the patient in supine position with legs apart. Four trocars (5-11 mm) were used for the procedure. The trocars were placed as follows (Figure 1): umbilicus (10 mm) for telescope; midpoint between the xiphoid and umbilicus, left of the midline (11 mm); right hand working and Endo-GIA, sub-xiphoid (5 mm) for liver retraction and PV and duodenum mesentery exposure; right anterior axillary line for subcostal (5 mm) bowel retraction.

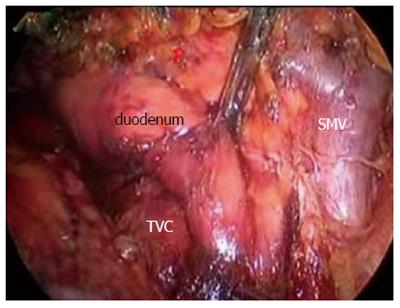

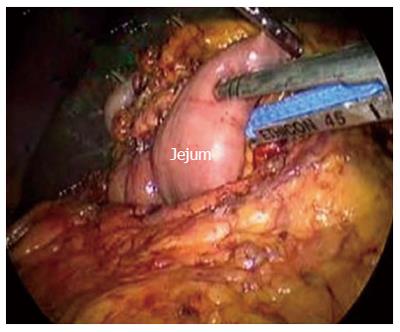

After establishing a pneumoperitoneum, laparoscopy was performed to inspect. A 5.0 MHz laparoscopic ultrasound probe (Aloka Prosound 5500, Aloka Co., Tokyo) was used to examine the liver, stomach, peritoneal cavity, and mesentery vessels. The gastrocolic ligament was divided using ultrasonic shears, and the lesser sac was widely exposed. The hepatic flexure of the colon was mobilized inferiorly, and a Kocher maneuver was performed. The SMV was identified at the inferior border of the pancreatic neck (Figure 2). The third and fourth portions of the duodenum and proximal jejunum were mobilized from the right to the left under the SM vessel while retracting the duodenum to the right. The jejunum was then transected 10-15 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz with the linear stapler (Figure 3).

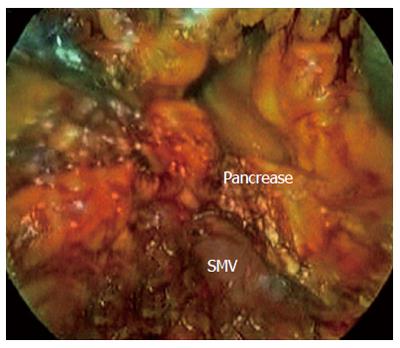

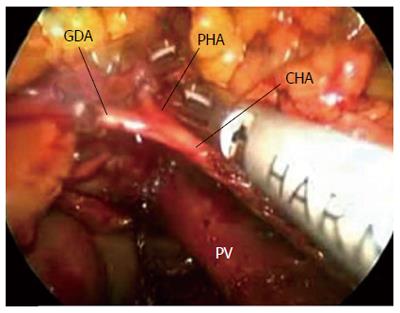

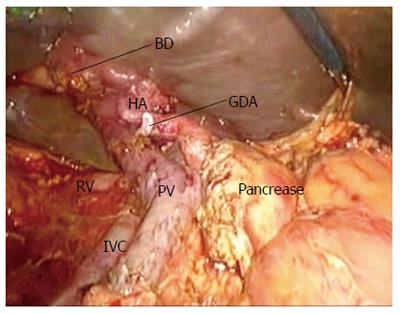

The specimens were then retracted in reverse to the right along the SMV and PV. The specimens were dissected from the jejunum mesentery vessels, duodenum mesentery vessels, and larger tributary vessels (pancreaticoduodenal vessels). An ultrasonic dissector was used to dissect the pancreatic head and uncinate process from the SMV, superior mesenteric artery, and PV. Simultaneously, the pancreatic neck parenchyma was divided with ultrasonic shears. At the superior boarder of the pancreas, the common hepatic artery and the gastroduodenal and right gastric arteries were identified and isolated from posterior to anterior (Figures 4,5,6,7). The arteries were clipped and divided, and the process was continued to isolate the proper hepatic artery and common bile duct along the PV. Retrograde cholecystectomy and a common hepatic bile duct transection were then performed. With the exception of the stomach, the specimens were divided. The sub-xiphoid trocar site was extended into a 5-7 cm incision at the anterior of the pancreas. The specimens were removed though the incision. All peripancreatic tissue including lymph nodes and nervous fibre was taken en bloc with the specimens. The specimens were transected 1-2 cm distal to the pyloric ring. The PV groove and the retroperitoneal/uncinate margin were inked, and separate bile duct and pancreatic neck margins were obtained prior to sending the specimens for frozen section analysis.

The jejunal stump was passed into the supramesocolic compartment and removed from the middle incision. Modified Roux-en-Y reconstruction procedures were performed by an open method through the retrieval incision. First, an ante-colic, end-to-side duodenojejunostomy was performed with two layers of running 3-0 proline. Based on Cattell’s work, an end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy was performed approximately 40-60 cm distal to the gastroenteric anastomosis.

The pancreatic duct was identified with a silicone tube. The dorsal pancreas was fastened to the seromuscular layer of the jejunum by passing suture thread though the intestinal wall and pancreatic parenchyma to the border 0.5-0.8 cm from the outer layer. The dorsal and ventral borders of the pancreas were sutured to the seromuscular layer of the jejunum with a running d 3-0 non-absorbable proline suture as an inner layer. Finally, the seromuscular layer of the jejunum was sutured with an outer layer of running 3-0 silk sutures over the inner layer at the ventral border to the pancreas capsule. This reconstruction was accomplished using a laparoscopic approach by inserting instruments through the retrieval incision. A lost anastomic stent was placed at the pancreaticojejunostomy. The hepaticojejunostomy was performed in laparoscopy with interrupted 4-0 absorbable Vicryl with a lost stent. The Braun anastomosis and the jejunojejunostomy were also performed extracorporeally in the same manner as the open method. No technical difficulties were encountered.

The patients were postoperatively fasted until the appearance of bowel activity. The patients were given postoperative narcotic analgesics for the first 24 h and were subsequently treated with nonnarcotic analgesics. The patients were discharged once they need not intravenous fluids and can be mobile independently. Any death within 30 d of surgery was included in perioperative mortality. Pancreatic fistula was diagnosed while the value of fluid amylase in drain output was greater than three times the serum amylase on or after the third postoperative day[8].

A total of 21 patients underwent LPD. One patient was converted to an open procedure following uncontrolled bleeding. The patient population included 13 women and 8 men. Their mean age was 65 years (SD, 11 years), and the median body mass index was 25 (range, 17-37). The median ASA score was II. The indication for pancreaticoduodenectomy included benign diseases in 3 (14.3%) patients and malignant diseases in 18 (85.7%) patients. The perioperative outcome is shown in Table 1. The LPD procedure for all patients was undertaken with curative intent. None of the patients had evidence of locally advanced, SMV vascular involvement, or metastatic disease.

| Characteristic | Median (range) |

| Patients | 21 |

| Age (yr) | 66 ± 12 |

| Body mass index | 25 (17-37) |

| ASA score | 3 (2-3) |

| Sex, female/male | 13/8 |

| Disease status | |

| Benign | 3 (14.3) |

| Malignant | 18 (73) |

| Parenchymal background (n) | |

| Soft | 9 |

| Intermediate | 6 |

| Solid | 6 |

| Type of procedure | |

| Pylorus-preserving | 14 (95) |

| Operative time (min) | 316 (260-410) |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 240 (30-1000) |

| Conversion rate | 1 (4.9) |

| Number of lymph nodes retrieved | 14 (8-26) |

The mean pancreatic duct and bile duct diameters were respectively 4 mm (range, 1.5-6 mm) and 12 mm (8-18 mm), respectively. The mean pancreatic operative time was 368 min (260-450 min), and the mean blood loss was 300 mL (100-1000 mL). At the completion of the procedure, a Jackson-Pratt drain was left near the pancreaticojejunostomy in all patients. The histologic findings included 6 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, 6 ampullary carcinomas, 3 pancreatic head adenocarcinomas, 2 intra-ductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, 2 pancreatic cystadenocarcinomas, and 2 biliary cancers. The mean tumor size was 3.1 cm (1.1-5cm), and the mean number of lymph nodes removed was 12 (7-26). In all of patients, an R0 resection (curative resection) was achieved. Regional lymph node metastases were found in 7 of 21 (33.3%) patients with malignancy. The pathologic outcomes are shown in Table 2.

| Diagnosis | n (%) |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | 6 |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | 2 |

| Ampullary adenocarcinoma | 8 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 2 |

| Cyst adenoma | 2 |

| Duodenal adenoma | 1 |

| Specimen characteristics | |

| Tumor size, median (range) (cm) | 3 (1.6-5.0) |

| Margin-negative, R0 resection | 20 (95) |

| Regional lymph node metastases | 5 (24) |

Perioperative complications occurred in 6 (24.8%) patients and included pancreatic anastomotic leak [n = 1 (4.9%)], delayed gastric emptying [n = 2 (9.7%)], postoperative pneumonia [n = 1 (4.9%)], and superficial surgical site infection [n = 1 (4.9%)] (Table 3).

| Modality | 5 (24.6) |

| Pancreatic anastomotic leak | 1 (4.9) |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 2 (9.7) |

| Postoperative pneumonia | 1 (4.9) |

| Surgical site infection | 1 (4.9) |

LPD represents one of the most advanced abdominal operations due to the complex dissection and enteric reconstruction. Despite being first described by Gagner[1] and Pomp in 1994, LPD is not a well-accepted procedure. Concerns regarding the use of LPD have increased as a result of the long operative time, requirement for advanced laparoscopic skills, and lack of perceived benefits over open approaches[9-12]. While the surgical procedure is complicated and difficult to perform, the surgical approach that is adopted by most authors[1-3,13,14] is similar to traditional open-surgery procedures and is inadequate for a laparoscopic approach. This is likely another factor delaying the acceptance of LPD. We have simplified the surgical procedure using an inverse-“V” approach. Our new surgical strategy has several advantages (Table 3). The approach involves dissecting the gastrocolic ligament and moving downward to isolate the transverse duodenum, moving upward to the jejunum to pull the duodenum to the right, and then removing the proximal jejunum from under the mesenteric vessel. Next, the jejunum is transected 10-15 cm from the proximal jejunum to the Treitz ligament. The jejunum is divided from the jejunum and duodenum mesentery to the mesenteric vessels and upwards to the hepatic portal triad adjacent to the SMV and PV. The surgical procedure route is convenient for laparoscopic dissection. Moreover, the route facilitates the finding and safe dissection of the hepatic artery, PV, and bile duct from the posterior aspect along the gap among the portal vein, hepatic artery, and bile duct. Additionally, this surgery can be performed with four ports. The traditional procedure requires more time to identify the relationship among the tumor, SMV, and PV before dissecting the hepatic artery, gastroduodenal artery, and SMV anteriorly[13-17]. In the current study, the mean operative time was 316 min, which is faster than previous reports (Table 4).

| Ref. | n | HA/total | OT (min) | EBL (mL) | PF n (%) | M n (%) | HS (d) |

| Gagner et al[1] 1994 | 2 | 2/0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gagner et al[2] 1997 | 10 | 2/8 | 510 | NA | 2 (20) | NA | NA |

| Dulucq et al[20] 2006 | 25 | 12/13 | 287 | 107 | NA | 27 | NA |

| Staudacher et al[21] 2005 | 4 | 4/0 | 416 | 325 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Mabrut et al[22] 2005 | 3 | 1/2 | 300 | 300 | NA | NA | 7 |

| Lu et al[23] 2006 | 5 | 0/5 | 528 | 770 | NA | 3 (60) | NA |

| Zheng et al[24] 2006 | 1 | NA | 390 | 50 | NA | NA | 30 |

| Palanivelu et al[17] 2007 | 42 | 0/42 | 370 | 65 | 3 (7.1) | NA | 10 |

| Cai et al[25] 2008 | 1 | 0/1 | 510 | 800 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Pugliese et al[3] 2008 | 19 | 7/6 | 482 | 180 | 3 (23.1) | 7 (54) | 18 |

| Sa Cunha et al[26] 2008 | 2 | 0/2 | 510 | 300 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 19 |

| Gumbs et al[13] 2008 | 3 | 0/3 | NA | NA | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | NA |

| Ammori et al[14] 2011 | 7 | 1/6 | 628 | 350 | 1 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) | 11 |

| Total | 124 | 28/76 | 448 | 325 | 11.6 | 22 (28.6) | 16 |

| The current study | 21 | 0/21 | 316 | 280 | 1 | 26.7 | 14 |

In the present series, the middle 5-7 cm incision was used to retrieve the specimen en bloc. Additionally, the incision was used to perform the extra corporal gastroenteric and enteroenteric anastomosis easily and safely. The gut reconstruction in laparoscopy is time-consuming and may cause the spread of bacteria. The anastomosis requires time to reconstruct by a Roux-en-Y anastomosis or physiologic repair. Our approach takes advantage of the retrieval incision to assist the pancreas-to-jejunum anastomosis using a mini-laparectomy technique. The benefits of the surgery include preventing pancreatic leakage and reducing the difficulty of anastomosis. The procedure is simple and effective and merits further investigation. The development of a pancreatic fistula (PF) is an Achilles heel for LPD[8,18,19], and laparoscopic pancreatic-enteric anastomosis is technically difficult and has a high risk of pancreatic leakage. The mean incidence of PF in LPD was reported as 28.6% (range, 0%-50%) (Table 4). In this series, we modified the anastomotic modes by two layering methods. Only one patient with preoperative pancreatitis had markedly increased amylase in the drain fluids, and we cannot differentiate the rise of amylase due to pancreatitis from that due to PF. However, the patient was successfully treated with a conservative treatment.

Advanced professional skills are required to decrease the operative time, morbidity, and surgeon frustration. Surgeons attempting LPD should have skillful experience on pancreatic surgery to avoid severe complications, and to perform the LPD according to oncologic standards of pancreatic resection. If LPD is performed in selected cases by highly skilled laparoscopic surgeons, the procedure is feasible, safe, and oncologically adequate. When the learning curve has been overcome, laparoscopy may improve postoperative outcomes in excellence centers. Multicenter randomized trials are needed to confirm this.

Based on our experience in open pancreaticoduodenectomies and laparoscopic surgery, as previous reported, LPD is feasible, safe, and advantageous in selected patients[10,12,27]. We established stringent criteria for selecting patients to treat with the laparoscopic approach. Early ampullary adenocarcinomas and cholangiocarcinomas are most amenable to a laparoscopic approach. Furthermore, patients with early pancreatic head carcinoma without lymph node or major vessel involvement and tumors smaller than 3 cm are suitable for laparoscopic surgery. Based on our experience with pancreatic surgery, laparoscopic ultrasound is a useful modality for assessing tumor resectability. Most patients can be correctly evaluated using contrast-enhanced triple-phase helical CT and diagnostic laparoscopy with laparoscopic ultrasound. In one patient cohort, the combination of these tools led to a diagnostic sensitivity of 100%[28]. The only conversion to open surgery in our series occurred in a patient with a tumor that was preoperatively located in the uncinate and was regarded as a relative indication for laparoscopy. The transection is also difficult and may cause bleeding. Therefore, after making the decision to remove the tumor based on an evaluation by triple-phase helical (multi-detector) CT and diagnostic laparoscopy with laparoscopic ultrasound, the present surgical approach directly dissects and divides the tissue around the tumor instead of investing time exploring whether the tumor has invaded a main vessel. This approach is another time-saving aspect of the procedure.

A sound operation is possible using the laparoscopic approach. In our series, all of the patients had a negative margin in the histopathology. The number of lymph node removed was adequate due to the magnification with the laparoscopy. Similar curative resection rate has been described by others[17,18,20]. The oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic procedure have not been compared with the open manner. This series lacks enough patients and follow-up time to evaluate the oncologic outcomes such as survival rate and tumor recurrence. However, possible surrogates to evaluate the oncologic procedure itself may include curative resection rate, the area of resection and the number of removed lymph nodes that were achieved. In this series, the oncologic outcomes were compared with those in the open manner, which suggests that LPD is not an inferior procedure.

This early experience suggests that LPD via an inverse-“V” approach is feasible and safe. The preoperative evaluation using imaging and diagnostic laparoscopy with laparoscopic ultrasound can make the present surgical approach feasible and efficacious. A randomized controlled trial may be required to confirm our conclusions.

To evaluate the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy (LPD) using a reverse-“V” approach with four ports.

The LPD procedure is not currently a well-accepted treatment approach. The concerns regarding the use of LPD stem from the long operative time, lack of apparent advantages, and the requirement of advanced laparoscopic skills.

LPD using a reverse-“V” approach can be performed safely and yields good results in elective patients. This preliminary experience showed that LDP can be performed via a reverse-“V” approach.

This approach can be used to treat localized malignant lesions irrespective of histopathology.

In this retrospective study, the authors evaluated the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of the modified laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Some revisions are needed.

P- Reviewer: Dubois A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:408-410. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: Is it worthwhile? J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:20-25; discussion 25-26. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Pugliese R, Scandroglio I, Sansonna F, Maggioni D, Costanzi A, Citterio D, Ferrari GC, Di Lernia S, Magistro C. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: a retrospective review of 19 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:13-18. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kooby DA, Gillespie T, Bentrem D, Nakeeb A, Schmidt MC, Merchant NB, Parikh AA, Martin RC, Scoggins CR, Ahmad S. Left-sided pancreatectomy: a multicenter comparison of laparoscopic and open approaches. Ann Surg. 2008;248:438-446. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 320] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Corcione F, Pirozzi F, Cuccurullo D, Piccolboni D, Caracino V, Galante F, Cusano D, Sciuto A. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: experience of 22 cases. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2131-2136. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zenoni SA, Arnoletti JP, de la Fuente SG. Recent developments in surgery: minimally invasive approaches for patients requiring pancreaticoduodenectomy. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:1154-1157. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Al-Taan OS, Stephenson JA, Briggs C, Pollard C, Metcalfe MS, Dennison AR. Laparoscopic pancreatic surgery: a review of present results and future prospects. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:239-243. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pratt WB, Callery MP, Vollmer CM. Risk prediction for development of pancreatic fistula using the ISGPF classification scheme. World J Surg. 2008;32:419-428. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 257] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Farid S, Morris-Stiff G. Laparoscopic vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:1220-1221. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gerstenhaber F, Grossman J, Lubezky N, Itzkowitz E, Nachmany I, Sever R, Ben-Haim M, Nakache R, Klausner JM, Lahat G. Pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly adults: is it justified in terms of mortality, long-term morbidity, and quality of life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1351-1357. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Asbun HJ, Stauffer JA. Laparoscopic vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy: overall outcomes and severity of complications using the Accordion Severity Grading System. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:810-819. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 313] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mesleh MG, Stauffer JA, Bowers SP, Asbun HJ. Cost analysis of open and laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single institution comparison. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4518-4523. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gumbs AA, Gayet B. The laparoscopic duodenopancreatectomy: the posterior approach. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:539-540. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ammori BJ, Ayiomamitis GD. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy: a UK experience and a systematic review of the literature. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2084-2099. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic hand-assisted pancreaticoduodenectomy: initial UK experience. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:717-718. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Kimura Y, Hirata K, Mukaiya M, Mizuguchi T, Koito K, Katsuramaki T. Hand-assisted laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreas head disease. Am J Surg. 2005;189:734-737. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Palanivelu C, Jani K, Senthilnathan P, Parthasarathi R, Rajapandian S, Madhankumar MV. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: technique and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:222-230. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 175] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Conlon KC, Labow D, Leung D, Smith A, Jarnagin W, Coit DG, Merchant N, Brennan MF. Prospective randomized clinical trial of the value of intraperitoneal drainage after pancreatic resection. Ann Surg. 2001;234:487-493; discussion 493-494. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Raut CP, Tseng JF, Sun CC, Wang H, Wolff RA, Crane CH, Hwang R, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, Lee JE. Impact of resection status on pattern of failure and survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246:52-60. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 437] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dulucq JL, Wintringer P, Mahajna A. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy for benign and malignant diseases. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1045-1050. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 121] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Staudacher C, Orsenigo E, Baccari P, Di Palo S, Crippa S. Laparoscopic assisted duodenopancreatectomy. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:352-356. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mabrut JY, Fernandez-Cruz L, Azagra JS, Bassi C, Delvaux G, Weerts J, Fabre JM, Boulez J, Baulieux J, Peix JL. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: results of a multicenter European study of 127 patients. Surgery. 2005;137:597-605. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Lu B, Cai X, Lu W, Huang Y, Jin X. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy to treat cancer of the ampulla of Vater. JSLS. 2006;10:97-100. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Zheng MH, Feng B, Lu AG, Li JW, Hu WG, Wang ML, Zang L, Dong F, Mao ZH, Peng YF. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of common bile duct: a case report and literature review. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:CS57-CS60. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Cai X, Wang Y, Yu H, Liang X, Xu B, Peng S. Completed laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:404-406. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sa Cunha A, Rault A, Beau C, Laurent C, Collet D, Masson B. A single-institution prospective study of laparoscopic pancreatic resection. Arch Surg. 2008;143:289-295; discussion 295. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 71] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jacobs MJ, Kamyab A. Total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. JSLS. 2013;17:188-193. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Baghbanian M, Salmanroghani H, Baghbanian A, Bakhtpour M, Shabazkhani B. Efficacy of multi-detector computerized tomography scan, endoscopic ultrasound, and laparoscopy for predicting tumor resectability in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32:376-380. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |