Published online Nov 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i42.12197

Peer-review started: April 29, 2015

First decision: June 2, 2015

Revised: July 3, 2015

Accepted: September 15, 2015

Article in press: September 15, 2015

Published online: November 14, 2015

AIM: To conduct a meta-analysis to investigate the clinical outcomes of surgical resection and locoregional treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in elderly patients defined as aged 70 years or more.

METHODS: Literature documenting a comparison of clinical outcomes for elderly and non elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma was identified by searching PubMed, Ovid, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases, for those from inception to March 2015 with no limits. Dichotomous outcomes and standard meta-analysis techniques were used. Heterogeneity was tested by the Cochrane Q statistic. Pooled estimates were measured using the fixed or random effect model.

RESULTS: Twenty three studies were included with a total of 12482 patients. Of these patients, 6341 were treated with surgical resection, 3138 were treated with radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and 3003 were treated with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). Of the patients who underwent surgical resection, the elderly had significantly more respiratory co-morbidities than the younger group, with both groups having a similar proportion of cardiovascular co-morbidities and diabetes. After 1 year, the elderly group had significantly increased survival rates after surgical resection compared to the younger group (OR = 0.762, 95%CI: 0.583-0.994, P = 0.045). However, the 3-year and 5-year survival outcomes with surgical resection between the two groups were similar (OR = 0.947, 95%CI: 0.777-1.154, P = 0.67 for the third year; and OR = 1.131, 95%CI: 0.895-1.430, P = 0.304 for the fifth year). Postoperative treatment complications were similar between the elderly and younger group. The elderly group and younger group had similar survival outcomes for the first and third year after RFA (OR = 1.5, 95%CI: 0.788-2.885, P = 0.217 and OR = 1.352, 95%CI: 0.940-1.944, P = 0.104). For the fifth year, the elderly group had significantly worse survival rates compared to the younger group after RFA (OR = 1.379, 95%CI: 1.079-1.763, P = 0.01). For patients who underwent TACE, the elderly group had significantly increased survival compared to the younger group for the first and third year (OR = 0.664, 95%CI: 0.548-0.805, P = 0.00 and OR = 0.795, 95%CI: 0.663-0.953, P = 0.013). At the fifth year, there were no significant differences in overall survival between the elderly group and younger group (OR = 1.256, 95%CI: 0.806-1.957, P = 0.313).

CONCLUSION: The optimal management strategy for elderly patients with HCC is dependent on patient and tumor characteristics. Compared to patients less than 70, elderly patients have similar three year survival after resection and ablation and an improved three year survival after TACE. At five years, elderly patients had a lower survival after ablation but similar survival with resection and TACE as compared to younger patients. Heterogeneity of patient populations and selection bias can explain some of these findings. Overall, elderly patients have similar success, if not better, with these treatments and should be considered for all treatments after assessment of their clinical status and cancer burden.

Core tip: The optimal management strategy for elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is dependent on patient and tumor characteristics. This meta-analysis suggests that surgical resection, transarterial chemoembolization, and radiofrequency ablation are safe and effective treatment options for elderly patients with HCC. Overall, elderly patients have similar success with these treatments compared to younger patients and should be considered for all treatments pending their clinical status and cancer burden.

- Citation: Hung AK, Guy J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly: Meta-analysis and systematic literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(42): 12197-12210

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i42/12197.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i42.12197

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common primary malignancy of the liver, has become the fifth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide[1]. The management of HCC is multi-disciplinary with a wide range of treatment options ranging from liver resection, liver transplantation, locoregional therapies including ablation and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), and molecular-targeting therapies[1-32]. As our society continues to age, there will be an increasing proportion of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. In China and South Korea, the mean age at HCC diagnosis was found to be 55-59 years[2]. In Europe and North America, the average age of HCC diagnosis is 63 to 65 years, and up to 75 years in low risk populations[5]. Although HCC is a worldwide public health problem, there are epidemiological differences in the incidence of HCC based on geographic location. In Asia, the overwhelming etiology continues to be endemic hepatitis B. In Western countries, the most common etiologies are hepatitis C and alcoholic cirrhosis.

HCC in the elderly population has been found to demonstrate distinct clinicopathological characteristics from the disease process in the younger population. Reports indicate that elderly patients with HCC were more likely to be female, possibly due to their longer life expectancy[3]. Elderly patients with HCC were more likely to have chronic hepatitis C[3]. Most hepatitis B carriers acquire the disease in the perinatal period via vertical transmission, whereas hepatitis C infection is usually acquired in adulthood. As a result of earlier acquisition of the virus, the average age of diagnosis of HBV-related HCC is usually 10 years earlier than that of HCV-related HCC[1]. In the elderly population with HCC, there is also a larger proportion of patients who are negative for both hepatitis B surface antigen and HCV antibody, as compared to younger patients[4]. Elderly patients with HCC have also been shown to be more likely to have a normal liver with a lower grade of background liver fibrosis[5]. Aging is associated with decreased liver mass, hepatic blood flow, and synthesis or metabolism of exogenous substrates[5]. Whether these physiological changes are associated with worse outcomes in elderly HCC patients remains is debatable.

The effect of age on cancer treatment allocation is controversial. In general, elderly patients are thought to have increased co-morbidities including cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, and renal insufficiency[1]. Whether elderly patients with HCC have equal access to and outcomes from treatment as compared to their younger counterparts is controversial, with some data to suggest increased co-morbidities and poorer functional status in elderly HCC patients[14]. In a large multicentre report by the Italian Liver Cancer group, it was shown that elderly patients with HCC were more likely to undergo percutaneous procedures and were less likely to undergo surgical resection and TACE[14]. The data regarding safety and clinical outcomes of locoregional therapies for HCC in the elderly population remains limited.

There are a wide variety of treatment options for HCC depending on the stage of disease. Current treatments include surgical resection, liver transplantation, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, radioembolization, percutaneous radiofrequency ablation, percutaneous ethanol injection, percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy, and molecular-targeted therapy with sorafenib. Most studies evaluating clinical outcomes of such treatments in the elderly have been limited by small sample size and have varying results[1,5,13,14]. Most reports have demonstrated comparable outcomes between elderly and younger patients[5,14,23]. Previous studies showed similar survival rates after surgical resection with the exception of Hirokawa et al[17] who reported better disease free survival in younger patients and Liu et al[20] who reported better overall survival in younger patients[18,21]. In respect to radio frequency ablation (RFA), there were two studies which showed better long term outcomes in the younger patients[26,27]. For TACE, previous studies have reported comparable outcomes with the largest study showing better outcomes in the elderly group[27]. In this meta-analysis, we analyze characteristics and clinical outcomes of elderly patients with HCC treated with different modalities including surgical resection, percutaneous radiofrequency ablation, and transarterial chemoembolizaton (TACE).

Literature documenting a comparison of clinical outcomes in elderly patients undergoing surgical and locoregional therapies for HCC was identified by searching PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases, for those from inception to March 2015 with no limits.

The inclusion criteria for the present meta-analysis were as follows: published comparative studies reporting extractable data for survival outcomes for elderly and non elderly patients with HCC who underwent surgical resection, RFA, and TACE with elderly defined as aged 70 and above. Studies which included only Kaplan-Meier survival curves and did not include the number of annual survivals were not considered. A total of 125 references were identified through the literature search. Of these, 23 studies were included. All studies were observational and were either prospective or retrospective by design. Exclusion criteria included nonhuman studies, case reports, editorials, studies lacking control group of non elderly patients, studies in which patients were diagnosed with liver metastases or cholangiocarcinoma.

Demographics and clinical patient characteristics were thoroughly reviewed. Co-morbidities were assessed and included cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and diabetes. Cardiovascular co-morbidities included hypertension, arrhythmia, coronary artery occlusion, and old stroke. Respiratory co-morbidities included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. Treatment complications, defined as adverse events occurring within 30 d after operation or within the same hospitalization, were also assessed. Student’s t test was used to analyze significant differences in clinical characteristics between the elderly and younger patient groups.

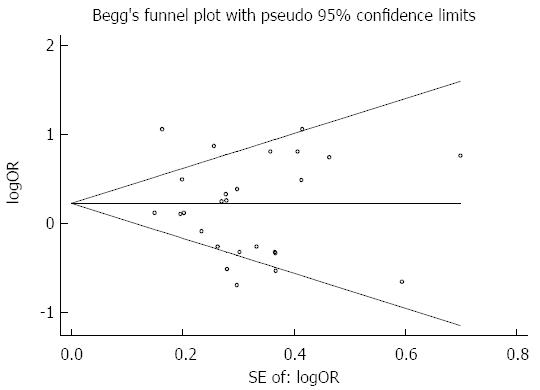

The meta-analyses were performed by STATA/SE 13.1 statistical software[6]. All analyzed data was treated as binary. Odds ratios and 95%CIs were computed from the binary data and used for the final meta-analyses. Both fixed and random effect models were calculated. Heterogeneity was assessed by the Cochrane Q test and was considered significant when P < 0.10. When there was substantially significant heterogeneity, a random effect model was used for meta-analysis. If heterogeneity was not significant, then a fixed effect model was used. In the meta-analysis, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Publication bias was analyzed using funnel plot.

The prevalence of viral hepatitis comparing the young and elderly cohorts is shown in Table 1. The younger patient population was more likely to have positive HBsAg. The proportion of HCV Ab infection was comparable between the elderly and younger patients.

| Study | Treatment | HBsAg positive (P = 0.023) | HCV Ab positive (P = 0.1681) | ||

| Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | ||

| Yau et al[27] | SR/RFA/TACE | 86.00% | 52.00% | NA | NA |

| Chen et al[7] | SR | 58.50% | 28.60% | NA | NA |

| Hanazaki et al[8] | SR | 23.70% | 18.40% | 40.70% | 55.40% |

| Yeh et al[9] | SR | 74.00% | 25.80% | 31.80% | 63.20% |

| Ferrero et al[10] | SR | 21.40% | 10.90% | 38.90% | 60.90% |

| Kaibori et al[11] | SR | 20.10% | 9.70% | 69.40% | 71.60% |

| Oishi et al[4] | SR | 23.70% | 1.56% | 66.00% | 70.00% |

| Huang et al[12] | SR | 88.80% | 65.70% | 1.10% | 7.50% |

| Mirici-Cappa et al[13] | SR | 15.00% | 7.10% | 47.10% | 57.10% |

| Tsujita et al[14] | SR | 23.00% | 8.70% | 70.60% | 87.00% |

| Yamada et al[15] | SR | 27.30% | 36.30% | 57.70% | 54.50% |

| Nishikawa et al[16] | SR | 17.50% | 4.35% | 56.30% | 66.30% |

| Hirokawa et al[17] | SR | NA | NA | 68.00% | 50.00% |

| Ide et al[18] | SR | 21.90% | 12.50% | 65.10% | 68.80% |

| Liu et al[20] | SR | 68.00% | 33.00% | 23.00% | 36.00% |

| Kishida et al[21] | SR | 31.00% | 5.00% | 43.00% | 55.00% |

| Kim et al[22] | SR | 64.50% | 28.80% | 7.80% | 18.60% |

| Takahashi et al[24] | RFA | 1.00% | 6.80% | 82.70% | 93.40% |

| Mirici-Cappa et al[13] | RFA | 13.00% | 5.60% | 52.20% | 74.40% |

| Nishikawa et al[25] | RFA | 11.30% | 1.54% | 73.90% | 86.90% |

| Liu et al[20] | RFA | 48.00% | 43.00% | 43.00% | 39.00% |

| Fujiwara et al[26] | RFA | 13.50% | 3.70% | 70.40% | 79.60% |

| Yau et al[27] | TACE | 87.00% | 63.00% | 10.00% | 18.00% |

| Mirici-Cappa et al[13] | TACE | 11.30% | 12.10% | 51.70% | 59.90% |

| Liu et al[20] | TACE | 52.00% | 37.00% | 35.00% | 35.00% |

| Nishikawa et al[28] | TACE | 15.50% | 0.00% | 58.30% | 71.20% |

Characteristics of patients who underwent surgical resection are shown in Table 2. Medical co-morbidities comparing the elderly vs younger patient populations are presented in Table 3. The elderly and younger patients were similar in respect to sex ratio, tumor size, cardiovascular complications, and diabetes. However, the elderly patients were more likely to have respiratory complications.

| Author | Year | Country | Design | Age cut off | Young, n | Elderly, n | Sex: male/female (P = 0.6947) | Child Pugh A/B | Tumor size (cm)(P = 0.984) | |||

| Y | E | Y | E | Y | E | |||||||

| Yau et al[27] | 1999 | China | Prospective | 70 | 299 | 31 | 255/44 | 21/10 | 285/14 | 30/1 | 7.9 | 8.0 |

| Wu et al[8] | 1999 | Taiwan | Retrospective | 80 | 239 | 21 | 190/49 | 19/2 | 194/34 | 16/4 | 6.5 | 7.0 |

| Hanazaki et al[8] | 2001 | Japan | Retrospective | 70 | 283 | 103 | 222/61 | 71/32 | 226/56 | 76/27 | NA | NA |

| Yeh et al[9] | 2004 | Taiwan | Prospective | 70 | 398 | 34 | 310/88 | 27/7 | 152/199 | 12/18 | 6.7 | 5.5 |

| Ferrero et al[10] | 2005 | Italy | Prospective | 70 | 177 | 64 | 145/32 | 47/17 | 138/37 | 54/8 | NA | NA |

| Kaibori et al[11] | 2009 | Japan | Retrospective | 70 | 333 | 155 | 269/64 | 119/36 | 302/31 | 139/16 | 4.32 | 3.76 |

| Oishi et al[4] | 2009 | Japan | Prospective | 75 | 502 | 64 | 381/121 | 48/16 | 427/NA | 59/NA | 3.3 | 3.9 |

| Huang et al[12] | 2009 | China | Retrospective | 70 | 268 | 67 | 222/46 | 58/9 | 257/11 | 63/4 | 7.4 | 7.3 |

| Mirici-Cappa et al[13] | 2009 | Italy | Retrospective | 70 | 43 | 142 | 116/26 | 32/11 | 123/18 | 40/3 | 4.09 | 3.42 |

| Tsujita et al[14] | 2012 | Japan | Prospective | 80 | 385 | 23 | 253/132 | 15/8 | 264/121 | 18/5 | 3.2 | 3.5 |

| Yamada et al[15] | 2012 | Japan | Prospective | 80 | 267 | 11 | 205/62 | 6/5 | 245/22 | 9/2 | 4.8 | 5.2 |

| Nishikawa et al[16] | 2013 | Japan | Prospective | 75 | 206 | 92 | 161/45 | 61/31 | 198/8 | 90/2 | 4.8 | 4.6 |

| Hirokawa et al[17] | 2013 | Japan | Retrospective | 70 | 120 | 100 | 99/21 | 69/31 | 98/22 | 88/12 | 3.0 | 3.5 |

| Ide et al[18] | 2013 | Japan | Retrospective | 75 | 192 | 64 | 157/35 | 43/21 | 168/24 | 57/7 | 4.9 | 4.9 |

| Taniai et al[19] | 2013 | Japan | Retrospective | 75 | 353 | 63 | 271/82 | 39/24 | 265/84 | 56/7 | NA | NA |

| Liu et al[20] | 2014 | Taiwan | Prospective | 75 | 730 | 129 | 571/159 | 107/22 | 694/36 | 116/13 | NA | NA |

| Kishida et al[21] | 2015 | Japan | Retrospective | 75 | 82 | 22 | 66/16 | 20/2 | NA | NA | 3.0 | 3.5 |

| Kim et al[22] | 2015 | South Korea | Retrospective | 70 | 219 | 60 | 168/51 | 46/14 | NA | NA | 4.9 | 4.9 |

| Author | Year | Country | CV co-morbidities (P = 0.341) | Resp co-morbidities (P = 0.031) | Diabetes (P = 0.086) | Alcohol (P = 0.737) | ||||

| Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | |||

| Yau et al[27] | 1999 | China | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chen et al[7] | 1999 | Taiwan | 47.60% | 12.60% | 8.40% | 14.30% | 5.40% | 14.30% | NA | NA |

| Hanazaki et al[8] | 2001 | Japan | 11.00% | 24.30% | 7.40% | 19.40% | 8.50% | 31.10% | NA | NA |

| Yeh et al[9] | 2004 | Taiwan | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15.30% | 38.20% | NA | NA |

| Ferrero et al[10] | 2005 | Italy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 31.10% | 20.30% |

| Kaibori et al[11] | 2009 | Japan | 16% | 39% | 4% | 16% | 7% | 23.00% | 48.30% | 35.40% |

| Oishi et al[4] | 2009 | Japan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Huang et al[12] | 2009 | China | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mirici-Cappa et al[13] | 2009 | Italy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 12.90% | 21.40% |

| Tsujita et al[14] | 2012 | Japan | 11.90% | 22.00% | 13.00% | 8.70% | 29.40% | 21.70% | NA | NA |

| Yamada et al[15] | 2012 | Japan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nishikawa et al[16] | 2013 | Japan | 13.10% | 50.80% | 10.70% | 15.20% | 33.50% | 26.00% | NA | NA |

| Hirokawa et al[17] | 2013 | Japan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ide et al[18] | 2013 | Japan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Taniai et al[19] | 2013 | Japan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Liu et al[20] | 2014 | Taiwan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15.00% | 10.00% |

| Kishida et al[21] | 2015 | Japan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 16.00% | 18.00% |

| Kim et al[22] | 2015 | South Korea | NA | NA | NA | NA | 13.70% | 25.00% | 3.20% | 5.10% |

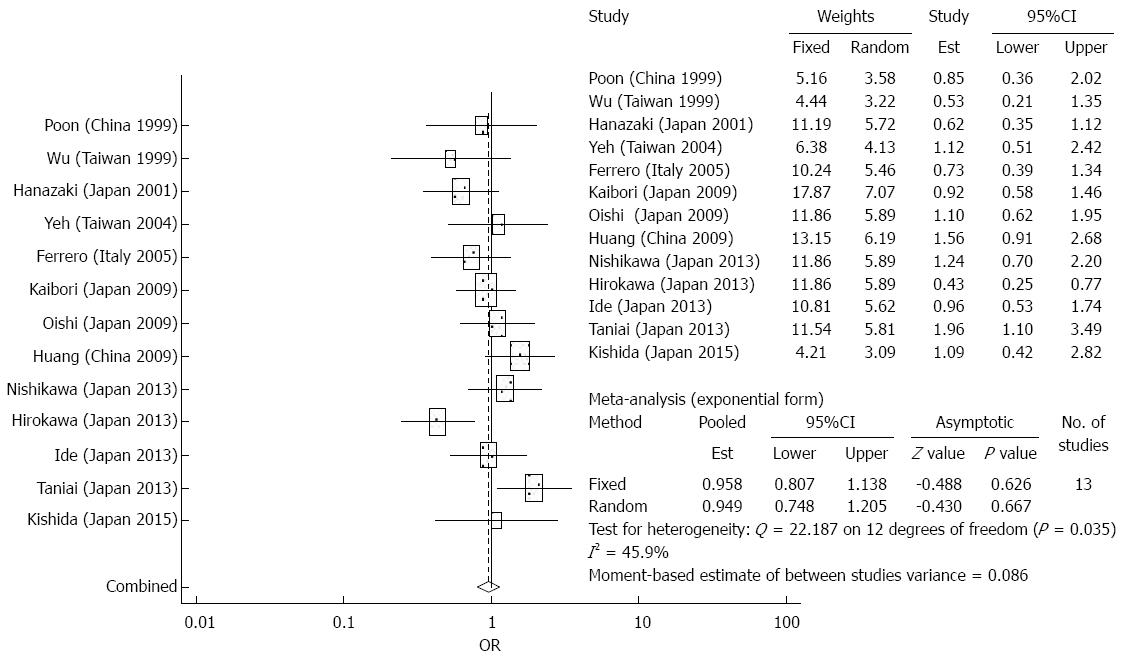

Overall survival: There were 9 studies which reported 1-year overall survival data, 13 studies which reported 3-year overall survival data, and 16 studies which reported 5-year survival data. After 1 year, the elderly group had significantly increased survival rates after surgical resection compared to the younger group (OR = 0.762, 95%CI: 0.583-0.994, P = 0.045). The meta-analysis demonstrated similar survival outcomes with surgical resection between the two groups (OR = 0.947, 95%CI: 0.777-1.154, P = 0.67 for the third year; and OR = 1.131, 95%CI: 0.895-1.430, P = 0.304 for the fifth year) (Figure 1). In terms of long term survival, the meta-analysis demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes of the elderly patients compared to younger patients, suggesting that surgical resection is a safe and effective treatment strategy for older patients. In the analysis of effects of overall survival at 1 year, there was no significant heterogeneity. There was substantial heterogeneity detected in the analysis of 5-year outcomes.

Disease free survival: The meta-analysis did not demonstrate any significant differences between the elderly and younger patients in terms of disease free survival after surgical resection (OR = 1.115, 95%CI: 0.815-1.359, P = 0.5488 for the first year; OR = 0.931, 95%CI: 0.730-1.189, P = 0.567 for the third year; and OR = 0.949, 95%CI: 0.748-1.205, P = 0.667 for the fifth year) (Figure 2). There was significant heterogeneity detected in the analysis of the effects of disease free survival rates.

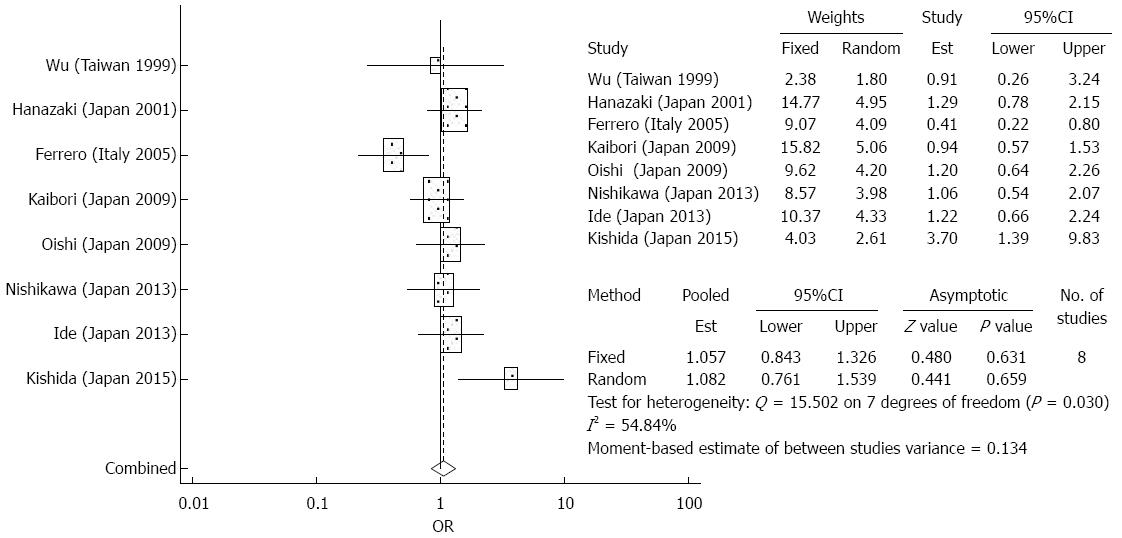

Treatment complications: The meta-analysis did not demonstrate any significant differences between the elderly and younger patient groups in terms of treatment complications after surgical resection (OR = 1.082, 95%CI: 0.761-1.539, P = 0.659) (Figure 3). There was significant heterogeneity detected in the analysis of the effects of complications. Among the most common complications were hemoperitoneum, bile leakage, intra abdominal abscess, and liver failure. Less common complications included ascites, pleural effusion, wound infection, prolonged jaundice, delirium, and renal failure.

Baseline characteristics and medical co-morbidities of HCC patients who underwent RFA are summarized in Table 4 and Table 5. Survival data of RFA between elderly and younger patients is shown in Table 6. The two populations were comparable in terms of tumor size, cardiovascular and respiratory co-morbidities, and diabetes. Elderly patients were more likely to be female. Younger patients were more likely to report alcohol use.

| Author | Year | Country | Design | Treatment | Age cut off | Young, n | Elderly, n | Sex: male/female (P = 0.031) | Child Pugh A/B/C | Tumor size (cm) (P = 0.662) | |||

| Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | ||||||||

| Takahashi et al[24] | 2010 | Japan | Prospective | RFA | 75 | 354 | 107 | 218/136 | 46/61 | 278/76 | 77/30 | NA | NA |

| Mirici-Cappa et al[13] | 2010 | Italy | Retrospective | RFA or PEI | 70 | 230 | 195 | 165/65 | 118/77 | 147/70/10 | 157/33/2 | 3.04 | 3.13 |

| Nishikawa et al[25] | 2012 | Japan | Prospective | RFA | 75 | 238 | 130 | 150/88 | 67/63 | 145/36/4 | 87/16 | 1.92 | 2.31 |

| Liu et al[20] | 2014 | Taiwan | Prospective | RFA | 75 | 336 | 147 | 221/115 | 96/51 | 80/17/3 | 89/11 | NA | NA |

| Fujiwara et al[26] | 2014 | Japan | Retrospective | RFA | 75 | 1048 | 353 | 705/343 | 191/162 | 782/255/11 | 287/63/3 | 2.40 | 2.50 |

| Author | Year | Country | Design | Age cut off | Young, n | Elderly, n | Alcohol (P = 0.031) | CV comorbidities (P = 0.446) | Resp comorbidities (P = 0.474) | DM (P = 0.602) | ||||

| Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | |||||||

| Takahashi et al[24] | 2010 | Japan | Prospective | 75 | 354 | 107 | 24.9% | 8.4% | 7.9% | 13.1% | 3.4% | 9.3% | 21.4% | 16.8% |

| Mirici-Cappa et al[13] | 2010 | Italy | Retrospective | 70 | 230 | 195 | 12.6% | 5.6% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nishikawa et al[25] | 2012 | Japan | Prospective | 75 | 238 | 130 | NA | NA | 15.1% | 34.6% | 13.9% | 25.4% | 34.9% | 28.5% |

| Liu et al[20] | 2014 | Taiwan | Prospective | 75 | 336 | 147 | 19.0% | 10.0% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Fujiwara et al[26] | 2014 | Japan | Retrospective | 75 | 1048 | 353 | 15.9% | 11.9% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Author | Year | Young, n | Elderly, n | 1-yr overall survival | 3-yr overall survival | 5-yr overall survival | P value | |||

| Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | |||||

| Takahashi et al[24] | 2010 | 354 | 107 | NA | NA | 80.0% | 82.0% | 63.0% | 61.0% | 0.824 |

| Mirici-Cappa et al[13] | 2010 | 230 | 195 | 89.9% | 90.1% | 52.9% | 53.4% | 35.1% | 29.0% | 0.797 |

| Nishikawa et al[25] | 2012 | 238 | 130 | 97.6% | 90.0% | 83.7% | 64.1% | 64.0% | 44.8% | 0.001 |

| Liu et al[21] | 2014 | 336 | 147 | 95.0% | 96.0% | 81.0% | 78.0% | 65.0% | 65.0% | 0.690 |

| Fujiwara et al[26] | 2014 | 1048 | 353 | 97.3% | 95.5% | 82.3% | 75.6% | 62.9% | 52.7% | < 0.001 |

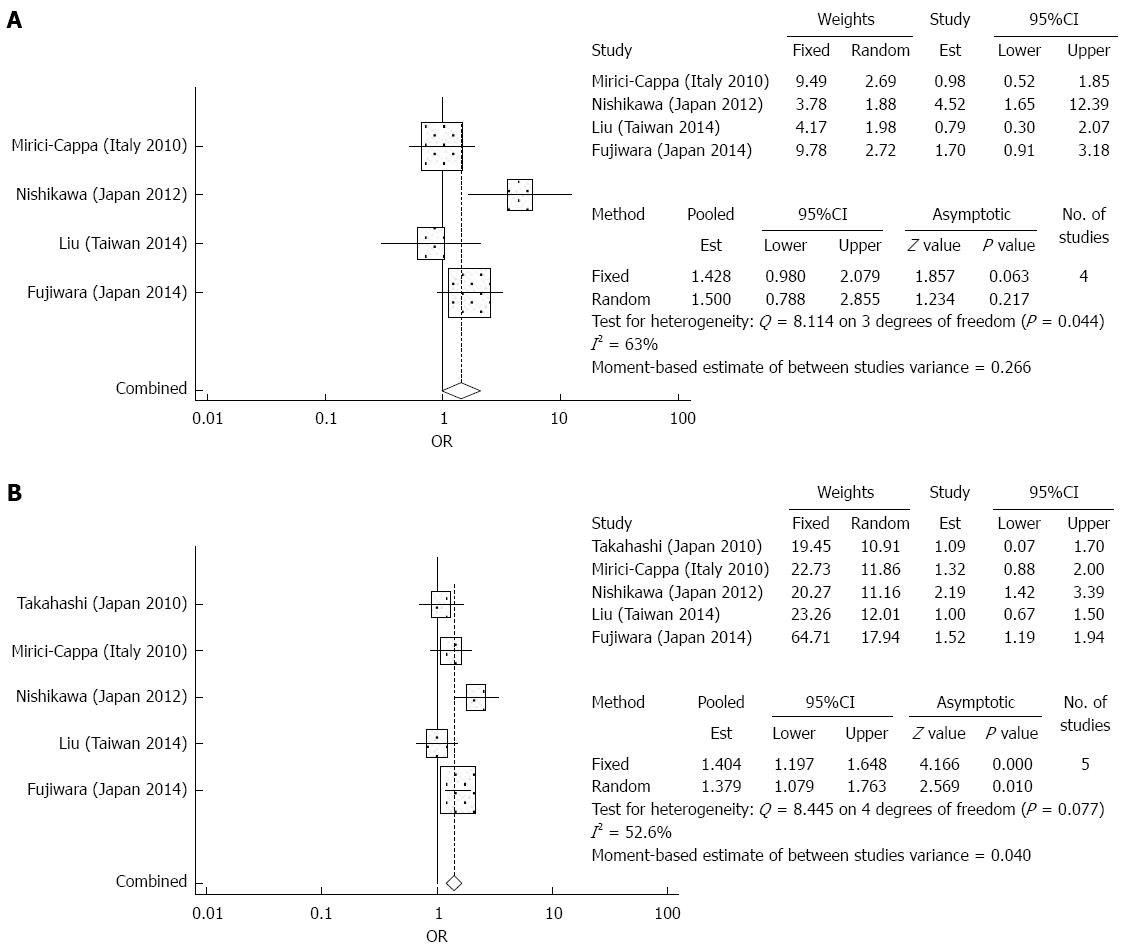

Overall survival: There were 4 studies which reported 1-year outcomes and 5 studies which reported 3-year, and 5-year overall survival data. The elderly group and younger group had similar survival outcomes for the first and third year after RFA (OR = 1.5, 95%CI: 0.788-2.885, P = 0.217 and OR = 1.352, 95%CI: 0.940-1.944, P = 0.104). For the fifth year, the elderly group had significantly worse survival rates compared to the younger group after RFA (OR = 1.379, 95%CI: 1.079-1.763, P = 0.01) (Figure 4). In the analysis of effects of overall survival, there was significant heterogeneity detected.

Treatment complications: The meta-analysis did not demonstrate any significant differences between the elderly and younger patient groups in terms of treatment complications after RFA (OR = 1.018, 95%CI: 0.522-1.987, P = 0.958) (Figure 5). There was no significant heterogeneity detected in the analysis of the effects of complications. Among the most common complications were hemoperitoneum, liver abscess, hemothorax, subcutaneous hematoma, and asymptomatic biloma[25,27]. Less common complications included pneumothorax, hemobilia, massive hepatic infarction, and gastrointestinal perforation[25,27].

Baseline characteristics of HCC patients who underwent TACE are summarized in Table 7. Survival data between elderly and younger patients who underwent TACE is shown in Table 8. The two populations were comparable in regards to sex ratio, tumor size, median survival in months, as well as 30 d mortality.

| Author | Year | Country | Design | Tx | Age cut off | Young, n | Elderly, n | Sex: male/female (P = 0.272) | Child Pugh A/B/C | Tumor size (cm) (P = 0.953) | |||

| Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | Young | Elderly | ||||||||

| Yau et al[27] | 2009 | China | Prospective | TACE | 70 | 317 | 67 | 272/45 | 54/13 | 262/55 | 52/15 | 8.70 | 8.50 |

| Yau et al[27] | 2009 | China | Prospective | TACE | 70 | 843 | 197 | 715/128 | 143/54 | 674/159/10 | 165/32 | NA | NA |

| Mirici-Cappa et al[13] | 2010 | Italy | Retrospective | TACE | 70 | 396 | 158 | 301/95 | 117/41 | 234/135/21 | 113/40/3 | 3.89 | 3.86 |

| Liu et al[20] | 2014 | Taiwan | Prospective | TACE | 75 | 604 | 271 | 446/158 | 222/49 | 72/22/3 | 86/14 | NA | NA |

| Nishikawa et al[28] | 2014 | Japan | Prospective | TACE | 75 | 84 | 66 | 63/21 | 34/32 | 52/32 | 53/13 | 5.10 | 5.70 |

| Author | Age cut off | Young, n | Elderly, n | Median survival (mo) (P = 0.683) | Post Op complication (P = 0.854) | 30-d mortality (P = 0.698) | 1-yr overall survival | 3-yr overall survival | 5-yr overall survival | P value | ||||||

| Y | E | Y | E | Y | E | Y | E | Y | E | Y | E | |||||

| Yau et al[27] | 70 | 317 | 67 | 9 | 12 | 26.0% | 24.0% | 5.0% | 7.0% | 41.0% | 53.0% | 18.0% | 25.0% | 13.0% | 17.0% | 0.277 |

| Yau et al[27] | 70 | 843 | 197 | 8.1 | 14 | 26.9% | 24.4% | 3.5% | 4.7% | 39.2% | 54.4% | 14.9% | 23.2% | 8.4% | 10.6% | < 0.003 |

| Mirici-Cappa et al[13] | 70 | 396 | 158 | 27 | 26 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 78.9% | 79.4% | 32.0% | 36.4% | 13.3% | 6.4% | 0.730 |

| Liu et al[20] | 75 | 604 | 271 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 79.0% | 84.0% | 57.0% | 57.0% | 42.0% | 39.0% | 0.953 |

| Nishikawa et al[28] | 75 | 84 | 66 | 29.3 | 34.8 | 6.0% | 5.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 78.2% | 84.1% | 39.3% | 48.0% | 33.8% | 15.0% | 0.887 |

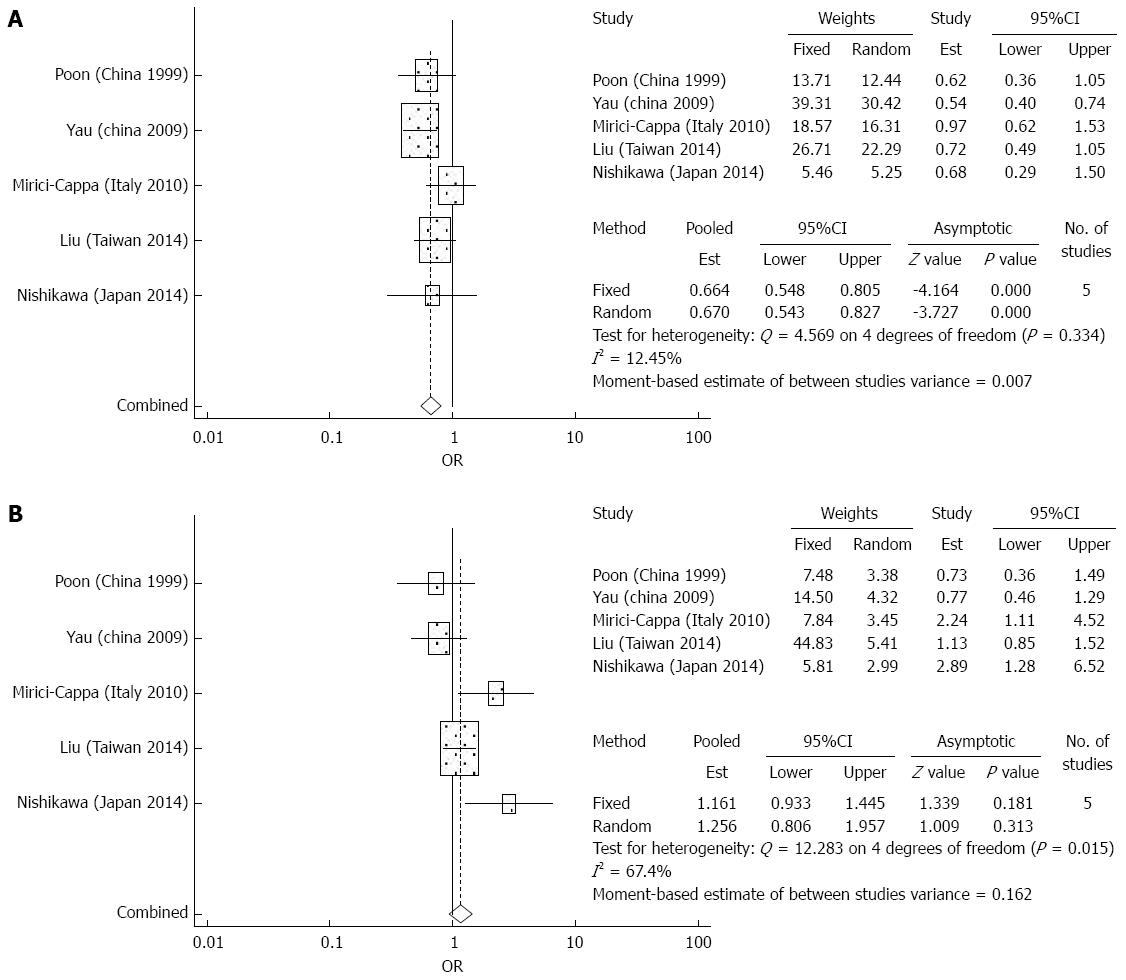

Overall survival: There were 5 studies which reported 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year overall survival data after TACE. The meta-analysis demonstrated significantly increased survival in the elderly group compared to the younger group for the first and third year (OR = 0.664, 95%CI: 0.548-0.805, P = 0 and OR = 0.795, 95%CI: 0.663-0.953, P = 0.013). At the fifth year, there were no significant differences in overall survival between the elderly group and younger group (OR = 1.256, 95%CI: 0.806-1.957, P = 0.313) (Figure 6). There was significant heterogeneity detected in the analysis of overall survival rates.

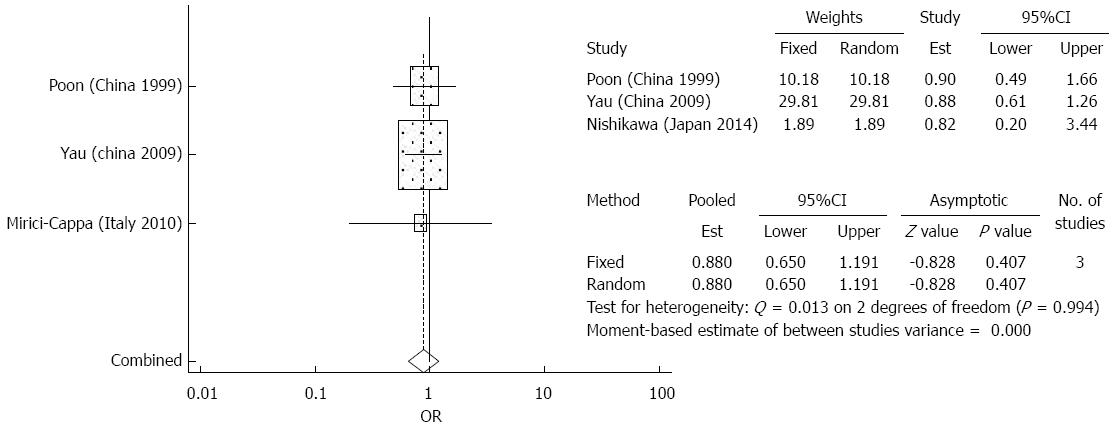

Treatment complications: The meta-analysis did not demonstrate any significant differences between the elderly and younger patient groups in terms of treatment complications after TACE (OR = 0.880 95%CI: 0.650-1.191, P = 0.407) (Figure 7). There was no significant heterogeneity detected in the analysis of the effects of complications. Among the most common complications were liver failure, liver abscess, peptic ulcers, and renal impairment[5,28,29]. Less common complications included acute pancreatitis, acute cholecystitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and hepatic artery dissection[5,28,29]. No significant heterogeneity was detected in the analysis of effects of treatment complications.

Publication bias was assessed by symmetry of Begg’s funnel plot (Figure 8). All the studies included had comparative data for 5-year overall survival. Level of symmetry was found to be high, indicating that there was no significant publication bias.

As the prevalence of older patients with HCC has increased, there has been ongoing debate regarding appropriate treatment strategies for these patients. Multiple treatment options are available for HCC patients, with treatment allocation determined by multiple factors including patient clinical characteristics, tumor burden, and geographic variations in treatment expertise and utilization[7]. Our aim was to determine if age is an important contributor to patient survival after resection, ablation and chemoembolization. Given the relatively fewer number of patients eligible for liver transplantation in this population, this treatment strategy was not specifically evaluated in our study.

Surgical resection is a potentially curative option for the elderly patient. According to BCLC staging and treatment algorithm, surgical resection is indicated in HCC patients with a single tumor, PS 0, Child-Pugh class A, and no portal hypertension[31,32]. Among the studies analyzed in this meta-analysis, the elderly and younger patient populations did not differ significantly in terms of male: female sex ratio and tumor size. In terms of co-morbidities, the elderly patients had a higher proportion of respiratory disease. The proportion of cardiovascular disease and diabetes did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Our meta-analysis demonstrated that immediate surgical complications were also not significantly different between elderly and younger patients. In terms of long term outcomes, overall survival was similar between elderly and younger patients. Huang et al[12] reported that elderly patients actually had a significantly increased overall survival rate compared to non elderly patients[13]. Huang also found lower hepatitis B surface antigen positive rate, higher hepatitis C virus infection rate, and more preoperative co-morbidities in the elderly population. Hirokawa et al[17] found that disease free survival was worse in elderly patients compared to non elderly patients after surgical resection[18]. Like in many other studies with elderly patients and HCC, they found a high prevalence of HCV infection[18]. Disease free survival was stratified to response to interferon in HCV-infected patients and the study showed that responders to IFN had significantly increased survival to non responders. Generally, elderly patients have had poor response to interferon therapy due to severe side effects. Improvements of antiviral therapy with the newer oral agents could possibly lead to improvements in disease free survival in elderly HCC patients with HCV infection.

Radiofrequency ablation has become an increasingly popular option for the elderly HCC patient[14]. The AASLD and EASL guidelines present RFA as a potential treatment option for compensated cirrhotic patients with good functional status and lesions less than 5 cm in size[31,32]. There have not been many studies investigating the outcomes of RFA in elderly patients. In our analysis of preoperative patient characteristics, we found that there was a higher proportion of females in the elderly population and a higher proportion of alcohol use in the younger patient population. The proportion of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory disease were similar in both patient groups. Our meta-analysis demonstrated no significant differences in 1-year and 3-year overall survival in elderly and non elderly patients who underwent RFA. At 5 years, the younger had significantly better clinical outcomes. As the data regarding long term outcomes of elderly patients with RFA continues to be lacking, the meta-analysis is limited by a small number of studies and showed significant heterogeneity. Similar to our findings, Fujiwara et al[26] also showed lower mortality at 5 years in the elderly patients. However, an additional risk analysis demonstrated that there was a significant difference in liver-unrelated death between the elderly and younger patients[26]. This suggested that elderly patients tended to die from liver-unrelated causes at 5 years. Nishikawa et al[25] demonstrated decreased cumulative overall survival and disease free survival at 1-, 3-, and 5-year intervals in the elderly patient group[26]. The results in this study were poorer compared to other reports. Both Nishikawa et al[25] and Fujiwara et al[26] did not demonstrate any significant differences in terms of duration of hospitalization and serious adverse events, suggesting that RFA is a safe procedure for elderly patients. Although limited by a small number of studies, our meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference in treatment complications among the elderly patients and their younger counterparts.

Transarterial chemoembolization is recommended for unresectable, Child-Pugh class A or B patients with multiple HCC with no vascular invasion. In terms of treatment complications, we found that there was no significant difference between the elderly patients and their younger counterparts. Our meta-analysis demonstrated increased overall survival in the elderly patients at 1-year and 3-year intervals. At 5 years, there were no significant differences in clinical outcomes between the elderly and younger patients. There was no significant difference in postoperative complications and 30 d mortality between the two groups. A study by Mondazzi et al[29] demonstrated that the independent prognostic factors affecting survival in elderly patients undergoing TACE were tumor stage, tumor markers, and hepatic functional reserve. Advanced age was not shown to be an adverse predictor of decreased survival[30]. Our TACE meta-analysis is also limited by a small number of studies and heterogeneity. The largest study conducted by Yau et al[27] showed increased overall median survival and disease-specific survival in elderly patients compared to younger patients. There are only a limited number of studies on the clinical outcomes of TACE in the elderly. In the studies that were analyzed, co-morbidities of the elderly patients including cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and diabetes were not included. Further investigation is warranted, but given the limited data, TACE also appears to be a safe treatment option for elderly HCC patients.

This meta-analysis suggests that age should not be a negative factor when considering treatment allocation and outcomes given equivalent survival and complications with resection, ablation, and TACE between younger and older patients. In the largest cohort of elderly HCC patients published, Liu et al[20] used propensity score analysis system to match elderly and younger HCC patients and similarly did not find an association with advanced age and inferior long-term survival for HCC patients receiving surgical resection, RFA, and TACE. In that study, 74% of younger patients received curative treatment as the initial treatment, as compared to 67% of elderly patients. Elderly patients were less likely to undergo surgical resection and instead received RFA or TACE compared to younger patients. The elderly patients were more likely to have compensated cirrhosis, lower AFP, fewer tumors with smaller tumor volume, and less vascular invasion but were more likely to advanced BCLC staging. It may seem contradictory that elderly HCC patients tend to have more advanced BCLC grading, but less advanced cancer. This may be explained by the incorporation of performance status in the BCLC grading system as the elderly patients did have poorer performance status compared to their younger counterparts. Advanced BCLC stage could also account for less resection. In this study, age was not found to be an independent predictor of poor prognosis. Thus, when deciding the optimal treatment strategy for elderly HCC patients, thorough evaluation based on cancer stage and general condition is important.

The majority of the studies included in the meta-analysis were done in eastern Asia, predominantly Japan and China. The clinical outcomes of elderly HCC patients in the western world, particularly in the United States, have not been thoroughly investigated. There is an urgent need for further investigation as HCC is becoming a global health problem. In the United States, reports suggest that HCC incidence peaks above the age of 70[2]. Most of the existing literature regarding elderly HCC patients pertains to chronic hepatitis B or C. In the western world, there is an increasing group of elderly HCC patients with non alcoholic fatty liver disease. There is limited data regarding the optimal treatment strategy of this group of patients as they also tend to have multiple co-morbidities. To increase external validity, further studies from western countries are desperately needed as the Asia Pacific region is a highly hepatitis B endemic area.

Several limitations to this meta-analysis exist. Studies included are observational cohorts by design given the lack of randomized controlled trials for HCC treatments. The multiple studies included in this review contain diverse patient demographic and geographic features resulting in significant heterogeneity. Few studies investigated the safety and validity of surgical resection, TACE, and RFA for elderly patients with HCC. Regarding other therapeutic options such as molecular-targeted therapy such as sorafenib, radioembolization, and liver transplantation, there is even less data on clinical outcomes in elderly HCC patients and therefore these modalities were not included in our analysis.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis suggests that surgical resection, TACE, and RFA are safe and effective treatment options for elderly patients with HCC. Overall, elderly patients have similar success with these treatments compared to younger patients and should be considered for all treatments pending their clinical status and cancer burden.

The authors would like to thank all the staff in our departments for their valuable support.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common primary malignancy of the liver, has become the fifth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. The management of HCC is multi-disciplinary with a wide range of treatment options ranging from liver resection, liver transplantation, locoregional therapies including ablation and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), and molecular-targeting therapies. As our society continues to age, there will be an increasing proportion of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. The optimal management strategy for elderly patients with HCC remains controversial.

There have been several studies done on elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, comparing their clinical outcomes to non-elderly patients. However, these studies are often limited by small sample size or heterogeneity. This is the first meta-analysis and systematic review to combine data from the multiple studies, in attempt to shed light on the safety and efficacy of various treatment modalities for hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly population.

Based on this meta-analysis, elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma have similar outcomes compared to non-elderly patients. Specifically, they have similar three year survival after resection and ablation and an improved three year survival after TACE, compared to non-elderly patients. At five years, elderly patients had a lower survival after ablation but similar survival with resection and TACE as compared to younger patients. Heterogeneity of patient populations and selection bias can explain some of these findings. Overall, elderly patients have good success with these treatments and should be considered for all treatments after assessment of their clinical status and cancer burden.

The findings from this meta-analysis can be used to guide the treatment approach of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. The analysis included clinical outcomes of locoregional therapies including surgical resection, chemoembolization, and radiofrequency ablation. The studies included were limited by heterogeneity with diverse patient demographic and geographic features. Further investigation is warranted regarding other therapeutic options such as molecular-targeted, radioembolization, and liver transplantation.

TACE is a minimally invasive procedure which involves injecting particles coated with chemotherapeutic agents into a tumor’s arterial supply. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is another minimally invasive procedure in which rapidly alternating current and electricity is delivered to a tumor to induce necrosis.

The aim of this meta-analysis was to investigate the clinical outcomes of surgical resection and locoregional treatments for HCC in elderly patients defined as aged 70 years or more. The authors suggest that surgical resection, TACE, and RFA are safe and effective treatment options for elderly patients with HCC. The elderly patients have similar success with these treatments compared to younger patients and should be considered for all treatments pending their clinical status and cancer burden. This manuscript is important as it will help to shed light on the management of HCC in the elderly population.

P- Reviewer: Pan GD, Zhu X S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Nishikawa H, Kimura T, Kita R, Osaki Y. Treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients: a literature review. J Cancer. 2013;4:635-643. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264-1273.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2183] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2337] [Article Influence: 194.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cohen MJ, Bloom AI, Barak O, Klimov A, Nesher T, Shouval D, Levi I, Shibolet O. Trans-arterial chemo-embolization is safe and effective for very elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2521-2528. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Oishi K, Itamoto T, Kobayashi T, Oshita A, Amano H, Ohdan H, Tashiro H, Asahara T. Hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients aged 75 years or more. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:695-701. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Miki D, Aikata H, Uka K, Saneto H, Kawaoka T, Azakami T, Takaki S, Jeong SC, Imamura M, Kawakami Y. Clinicopathological features of elderly patients with hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:550-557. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sharp S, Sterne J. sbe16: Meta-analysis. Stata Tech Bull. 1997;38:9-14. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Chen KW, Ou TM, Hsu CW, Horng CT, Lee CC, Tsai YY, Tsai CC, Liou YS, Yang CC, Hsueh CW. Current systemic treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A review of the literature. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1412-1420. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hanazaki K, Kajikawa S, Shimozawa N, Shimada K, Hiraguri M, Koide N, Adachi W, Amano J. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:38-46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yeh CN, Lee WC, Jeng LB, Chen MF. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:219-223. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Ferrero A, Viganò L, Polastri R, Ribero D, Lo Tesoriere R, Muratore A, Capussotti L. Hepatectomy as treatment of choice for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly cirrhotic patients. World J Surg. 2005;29:1101-1105. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kaibori M, Matsui K, Ishizaki M, Saito T, Kitade H, Matsui Y, Kwon AH. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:154-160. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang J, Li BK, Chen GH, Li JQ, Zhang YQ, Li GH, Yuan YF. Long-term outcomes and prognostic factors of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1627-1635. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mirici-Cappa F, Gramenzi A, Santi V, Zambruni A, Di Micoli A, Frigerio M, Maraldi F, Di Nolfo MA, Del Poggio P, Benvegnù L. Treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients are as effective as in younger patients: a 20-year multicentre experience. Gut. 2010;59:387-396. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 127] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tsujita E, Utsunomiya T, Yamashita Y, Ohta M, Tagawa T, Matsuyama A, Okazaki J, Yamamoto M, Tsutsui S, Ishida T. Outcome of hepatectomy in hepatocellular carcinoma patients aged 80 years and older. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1553-1555. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yamada S, Shimada M, Miyake H, Utsunomiya T, Morine Y, Imura S, Ikemoto T, Mori H, Hanaoka J, Iwahashi S. Outcome of hepatectomy in super-elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:454-458. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nishikawa H, Arimoto A, Wakasa T, Kita R, Kimura T, Osaki Y. Surgical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical outcomes and safety in elderly patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:912-919. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hirokawa F, Hayashi M, Miyamoto Y, Asakuma M, Shimizu T, Komeda K, Inoue Y, Takeshita A, Shibayama Y, Uchiyama K. Surgical outcomes and clinical characteristics of elderly patients undergoing curative hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1929-1937. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ide T, Miyoshi A, Kitahara K, Noshiro H. Prediction of postoperative complications in elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2013;185:614-619. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Taniai N, Yoshida H, Yoshioka M, Kawano Y, Uchida E. Surgical outcomes and prognostic factors in elderly patients (75 years or older) with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent hepatectomy. J Nippon Med Sch. 2013;80:426-432. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu PH, Hsu CY, Lee YH, Hsia CY, Huang YH, Su CW, Chiou YY, Lin HC, Huo TI. Uncompromised treatment efficacy in elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity score analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:e264. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kishida N, Hibi T, Itano O, Okabayashi K, Shinoda M, Kitago M, Abe Y, Yagi H, Kitagawa Y. Validation of hepatectomy for elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3094-3101. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim JM, Cho BI, Kwon CH, Joh JW, Park JB, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Paik SW, Park CK. Hepatectomy is a reasonable option for older patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2015;209:391-397. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chaimani A, Mavridis D, Salanti G. A hands-on practical tutorial on performing meta-analysis with Stata. Evid Based Ment Health. 2014;17:111-116. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Takahashi H, Mizuta T, Kawazoe S, Eguchi Y, Kawaguchi Y, Otuka T, Oeda S, Ario K, Iwane S, Akiyama T. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency ablation for elderly hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:997-1005. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nishikawa H, Osaki Y, Iguchi E, Takeda H, Ohara Y, Sakamoto A, Hatamaru K, Henmi S, Saito S, Nasu A. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical outcome and safety in elderly patients. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:397-405. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Fujiwara N, Tateishi R, Kondo M, Minami T, Mikami S, Sato M, Uchino K, Enooku K, Masuzaki R, Nakagawa H. Cause-specific mortality associated with aging in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing percutaneous radiofrequency ablation. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:1039-1046. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yau T, Yao TJ, Chan P, Epstein RJ, Ng KK, Chok SH, Cheung TT, Fan ST, Poon RT. The outcomes of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer. 2009;115:5507-5515. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nishikawa H, Kita R, Kimura T, Ohara Y, Takeda H, Sakamoto A, Saito S, Nishijima N, Nasu A, Komekado H. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical outcome and safety in elderly patients. J Cancer. 2014;5:590-597. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mondazzi L, Bottelli R, Brambilla G, Rampoldi A, Rezakovic I, Zavaglia C, Alberti A, Idèo G. Transarterial oily chemoembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. Hepatology. 1994;19:1115-1123. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208-1236. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4333] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4404] [Article Influence: 231.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6341] [Article Influence: 487.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Guy J, Kelley RK, Roberts J, Kerlan R, Yao F, Terrault N. Multidisciplinary management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:354-362. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |