Published online Oct 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i38.10883

Peer-review started: March 23, 2015

First decision: April 23, 2015

Revised: May 9, 2015

Accepted: August 31, 2015

Article in press: August 31, 2015

Published online: October 14, 2015

Processing time: 205 Days and 23.3 Hours

AIM: To estimate the prevalence of gastric cancer (GC) in a cohort of patients diagnosed with GC and to compare it with patients diagnosed with all other types of gastro-intestinal (GI) cancer during the same period.

METHODS: Between 2008 and 2013, five-year period, the medical records of all GI cancer patients who underwent medical care and confirm diagnosis of cancer were reviewed at the National Referral Hospital, Thimphu which is the only hospital in the country where surgical and cancer diagnosis can be made. Demographic information, type of cancer, and the year of diagnosis were collected.

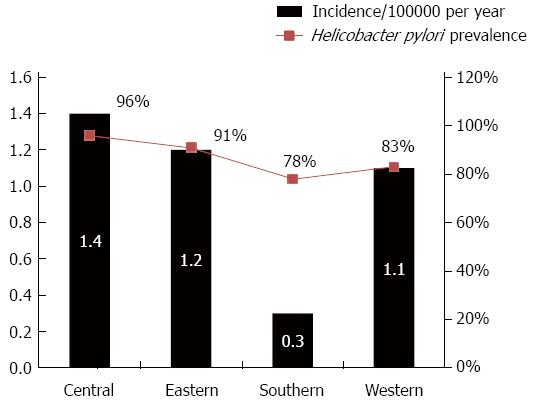

RESULTS: There were a total of 767 GI related cancer records reviewed during the study period of which 354 (46%) patients were diagnosed with GC. There were 413 patients with other GI cancer including; esophagus, colon, liver, rectum, pancreas, gall bladder, cholangio-carcinoma and other GI tract cancers. The GC incidence rate is approximately 0.9/10000 per year (367 cases/5 years per 800000 people). The geographic distribution of GC was the lowest in the south region of Bhutan 0.3/10000 per year compared to the central region 1.4/10000 per year, Eastern region 1.2/10000 per year, and the Western region 1.1/10000 per year. Moreover, GC in the South part was significantly lower than the other GI cancer in the same region (8% vs 15%; OR = 1.8, 95%CI: 1.3-3.1, P = 0.05). Among GC patients, 38% were under the age of 60 years, mean age at diagnosis was 62.3 (± 12.1) years with male-to-female ratio 1:0.5. The mean age among patients with all other type GI cancer was 60 years (± 13.2) and male-to-female ratio of 1:0.7. At time of diagnosis of GC, 342 (93%) were at stage 3 and 4 of and by the year 2013; 80 (23%) GC patients died compared to 31% death among patients with the all other GI cancer (P = 0.08).

CONCLUSION: The incidence rate of GC in Bhutan is twice as high in the United States but is likely an underestimate rate because of unreported and undiagnosed cases in the villages. The high incidence of GC in Bhutan could be attributed to the high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection that we previously reported. The lowest incidence of GC in Southern part of the country could be due to the difference in the ethnicity as most of its population is of Indian and Nepal origin. Our current study emphasizes on the importance for developing surveillance and prevention strategies for GC in Bhutan.

Core tip: The incidence rate of gastric cancer (GC) in Bhutan is twice as high in the United States but is likely an underestimate rate because of unreported and undiagnosed cases in the villages. The high incidence of GC in Bhutan could be attributed to the high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection that we previously reported. The lowest incidence of GC in Southern part of the country could be due to the difference in the ethnicity as most of its population is of Indian and Nepal origin. Our current study emphasizes on the importance for developing surveillance and prevention strategies for GC in Bhutan.

- Citation: Dendup T, Richter JM, Yamaoka Y, Wangchuk K, Malaty HM. Geographical distribution of the incidence of gastric cancer in Bhutan. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(38): 10883-10889

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i38/10883.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i38.10883

Gastric cancer (GC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality and the fourth most common cancer globally[1-3]. However, its incidence rates in different geographical regions are distinctly varied[2]. It been reported that in East Asia, high-risk countries include South Korea, Japan and China, where the age-standardized incidence rate is higher than 20 cases of GC per 100000 inhabitants per year[2]. The World Health Organization reports the incidence of GC in Bhutan to be very high[4]; however there is no published data yet. Bhutan is a small mountainous country bordering India and China and consists of four geographical regions, west, east, central, and south with a population consists of 800000 citizens.

It has been established that a Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is an etiologic agent of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease, GC and mucosal associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALT) and it is listed as a number one carcinogen[5-8]. We previously reported a very high prevalence of H. pylori in Bhutan[9,10]. Childhood hygiene practices and family education determine the prevalence of H. pylori infection[11,12]. The current study aimed to estimate the incidence of GC in Bhutan and to compare the geographic distribution of GC to our previously reported geographic distribution of H. pylori infection.

Between 2008 and 2013, five-year period, the medical records of all Gastro-Intestinal Cancer patients who underwent medical care and confirm diagnosis of cancer were reviewed at the National Referral Hospital, Thimphu which is the only hospital in the country where surgical and cancer diagnosis can be made. Diagnosis and ascertainment of the GC cases was based on endoscopic and pathological examination. There is only one surgeon in the country (TD) who operates on most/all the oncology cases in the country and there not yet established GC registry in Bhutan. Demographic information, e.g., age, gender, place of residence, and date of diagnosis were collected. For each patient, type of gastro-intestinal cancer was retrieved.

Bhutan is a remote Himalayan country between India and Tibet (China) with a population consists of only 800000 citizens residing in 18147 sq mi (47000 sq km) (Figure 1). Seventy percent of country is rural and agriculture based and the literacy rate is 47% (2011 Census). More than 30% of Bhutan populations live below poverty level. The climate in Bhutan varies with elevation, from subtropical in the south to temperate in the highlands and polar-type climate, with year-round snow in the north.

Bhutan is demographically divided into four main regions, Southern, Western, Eastern, and central regions. The Southern region shares border with India and ethnically they are of Indian and Nepal origin. The Western region is mostly on higher altitudes and socioeconomic standard is higher than Southern region. The normal water supply is through rural water scheme that is supported by the government and most people use local streams, rivers and piped water supply. The Central region shares similarity with the Western region both socioeconomically and geographically though it is little warmer. The Eastern region is lower in altitude than the Western region and have similar rural water supply scheme as the Western region.

Calculation of the crude incidence rate was based on the number of recorded cases divided by the overall population by the number of years. The estimated Bhutan population in 2005 was 800000.

There were a total of 767 GI related cancer records reviewed during the years of 2008 and 2013. There were 354 (46%) patients diagnosed with GC and 413 patients with diagnosed with esophagus, colon, liver, rectum, pancreas, gall bladder, cholangio-carcinoma and other types of GI cancers. The GC incidence rate was approximately 0.9/10000 per year (354 cases/5 years/800000 people). Among GC patients, 38% were under the age of 60 years, mean age at diagnosis was 62.3 (SD ± 12.1) years and the male-to-female ratio 1:0.5. The mean age among patients with all other type GI cancer was 60 years (± 13.2) and male-to-female ratio of 1:0.7. GC in the South part was significantly lower than the other GI cancer in the same region (8% vs 15%, OR = 1.8, 95%CI: 1.3-3.1, P = 0.05).

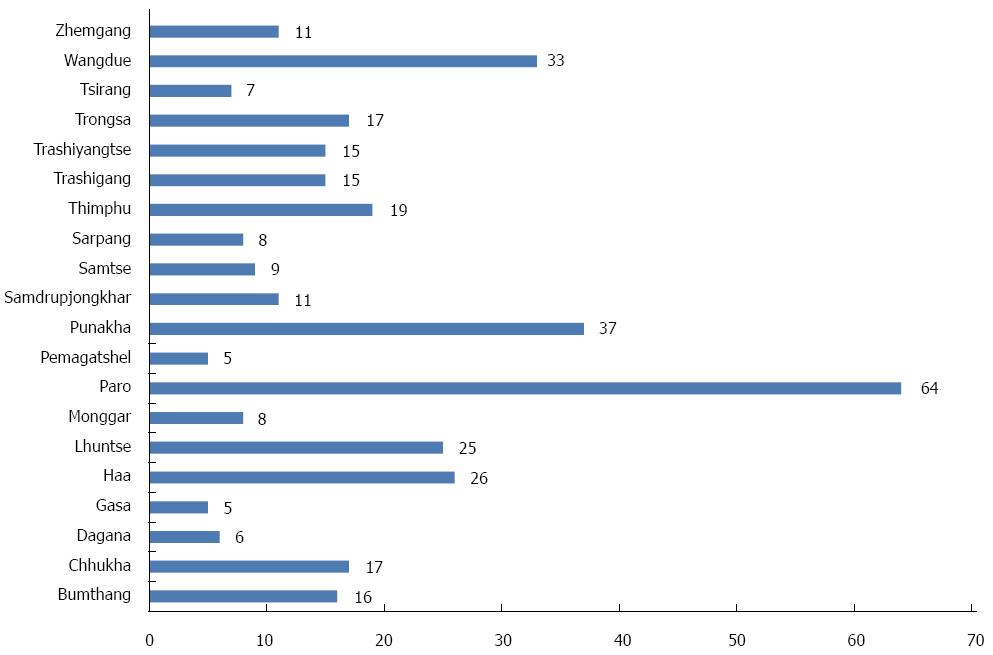

The geographic distribution of the overall number of GC cases by each city is presented in Figure 1. We calculated the incidence rate of GC by each region; we found that the geographic distribution of GC was the lowest in the Southern region of Bhutan 0.3/10000 per year compared to the central region 1.4/100000 per year, Eastern region 1.2/10000 per year, and the Western region 1.1/10000 per year (Figure 2). As we previously reported, the geographic distribution of H. pylori infection was the lowest in the south region of the country (Figure 3).

At time of diagnosis of GC, 10 (3%) of the patients were at stage 1, 15 (4%) at stage 2, 211 (60%) at stage 3 and 118 (33%) stage 4. By the year 2013; 79 GC patients (22%) died.

The latest estimate of the global incidence rates of GC was updated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer in 2008 report estimated that there were 989000 new cases of GC or (7.8% of all reported cancer cases)[1-3]. We found that the incidence rate of GC in Bhutan is high as it is second higher rate of cancer in the country after the incidence of cervical cancer (Unpublished data). The results of the current study add more emphasis to literature of the high GC incidence rate in South Asia, as the current study is the first report of the incidence of GC in Bhutan. In our previous study in Bhutan when we assessed subjects for gastric mucosal atrophy, we found that PG I/II ratio was significantly inversely correlated with the atrophy score in the antrum and the corpus. Furthermore, we found that the PG status was significantly associated with the presence of atrophy in the corpus and the prevalence of the PG-positive status was significantly higher among H. pylori-positive subjects than among H. pylori-negative subjects. We concluded that the high incidence of GC in Bhutan can be attributed to the high prevalence of H. pylori infection and gastric mucosal atrophy[13].

Geographic variations in GC incidence have been reported in both the West and the East[14-16]. Of interest our results revealed the lowest GC rate was found in south Bhutan than the rest of the country. This variation is consistent with our previous published results of the finding of the lowest H. pylori prevalence in the south part Bhutan[9]. The marked lower prevalence in the Southern region could be due is the different of the ethnicity in the region as they are of Indian and Nepal origin and they have different food habits than the original Bhutanese. It is known that Bhutanese are broadly from three ethnic backgrounds. The first ethnic group is from Tibetan descent that mainly from the Western parts of the country while the second is the Indo-Burmese ethnic group where mostly from the population in the Eastern parts of the country, the Southern Bhutanese, the third group, is of the Nepali origin and mainly Aryan descent. Migration studies have shown that first-generation migrants from countries with a high incidence of H. pylori infection relocating to countries of low incidence rates had similar risks as that of the country of origin, but the incidence rate tended toward that of the host country in subsequent generations, suggesting the important role of environmental risk factors[17-20]. Moreover, various biological strains could be present in different parts of the country and within individuals. A study published that Indian H. pylori isolates have been shown to have European origins and are widely held to be only mildly pathogenic[21].

The high incidence of GC in Bhutan could be attributed to the high prevalence of H. pylori infection that we previously reported. Moreover, it was also reported that host genetic have an impact on host responses to gastric inflammation and acid secretion, thereby interacting with H. pylori infection in gastric carcinogenesis. Therefore, host genetic factors may determine why some individuals infected with H. pylori develop GC, while others do not[22].

It has been established that a H. pylori infection is an etiologic agent of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease, GC and MALT and it is listed as a number one carcinogen[1-4]. Several studies and randomized controlled trials showed that H. pylori eradication reduce GC incidence by at least 35%[23-28]. Current consensus is that H. pylori screening and treatment is effective only in high-risk populations[29-32]. However, up till today such screening/surveillance had not taken place yet in Bhutan in spite the high prevalence of H. pylori infection and high GC rate among all age groups.

The current study revealed that 95% of GC patients were diagnosed at stages 3 and 4 and accordingly this could result in a higher mortality than early diagnosis. Early cancer detection is important because countries that perform GC surveillance, such as Japan and Korea, have lower mortality rates[3]. The Asian-Pacific Consensus Group recommended the screening and treatment of H. pylori as an evidenced-based and reasonable strategy for primary prevention of GC in selected communities where the burden of GC is high[32].

It has been well documented that treatment of H. pylori infection has an impact on the precursors of GC. A study from Colombia, a region with high GC risk, assessed the effect of H. pylori eradication therapy on intestinal metaplasia, multifocal atrophy and dysplasia in reported significant regression in histopathology score after treatment[33-36]. A recent study from Taiwan reported that mass eradication of H. pylori infection resulted in significant reduction in incidence of gastric atrophy resulting from chemoprevention[37]. Adopting the 2008 Asia-Pacific guidelines for a low threshold for treatment of symptomatic patients, as well as low cost follow-up testing could significantly lower the prevalence of peptic ulcer disease, GC. Therefore, there it is a great need for developing surveillance and prevention strategies for GC in Bhutan.

The utilization of the current data for constructing our study has some shortcomings that should be addressed. The main limitation is that we relied on the hospital records and not GC registry to identify the cancer cases. However, up till today, there is no cancer registry in Bhutan and the Timphu National hospital is the only hospital that diagnoses all cancer cases in the country, so our data is valid as representative GC cases in Bhutan. The second limitation of the study that we did not have enough data to calculate the overall mortality rate due GC and further studies are highly needed to address that topic.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates clear evidence of the high GC incidence in Bhutan that could be attributed to the high prevalence of H. pylori infection that we previously reported. The lowest incidence of GC in Southern part of the country could be due to the difference in the ethnicity as most of its population is of Indian and Nepal origin. Our current study emphasizes on the importance for developing surveillance and prevention strategies for GC in Bhutan.

The World Health Organization reports the incidence of gastric cancer (GC) in Bhutan to be very high; however there is no published data yet. GC is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality and the fourth most common cancer globally. However, its incidence rates in different geographical regions are distinctly varied. It has been established that a Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is an etiologic agent of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease, GC and mucosal associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and it is listed as as a number one carcinogen.

The authors performed a retrospective study on a cohort of patients estimate the incidence of GC in Bhutan and to compare the geographic distribution of GC to our previously reported geographic distribution of H. pylori infection.

The incidence rate of GC in Bhutan is twice as high in the United States but is likely an underestimate rate because of unreported and undiagnosed cases in the villages.

The high incidence of GC in Bhutan could be attributed to the high prevalence of H. pylori infection that the authors previously reported. The lowest incidence of GC in Southern part of the country could be due to the difference in the ethnicity as most of its population is of Indian and Nepal origin. It is of importance for developing surveillance and prevention strategies for GC in Bhutan.

This is an interesting and well written paper.

P- Reviewer: Razis E S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Ang TL, Fock KM. Clinical epidemiology of gastric cancer. Singapore Med J. 2014;55:621-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893-2917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11128] [Cited by in RCA: 11776] [Article Influence: 841.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v2.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Online]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. |

| 4. | Stomach cancer statistics. Stomach cancer is the fifth most common cancer in the world, with 952000 new cases diagnosed in 2012. Available from: http://www.wcrf.org/cancer_statistics/data_specific_cancers/stomach_cancer_statistics.php. |

| 5. | Correa P, Fox J, Fontham E, Ruiz B, Lin YP, Zavala D, Taylor N, Mackinley D, de Lima E, Portilla H. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinoma. Serum antibody prevalence in populations with contrasting cancer risks. Cancer. 1990;66:2569-2574. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Forman D. The etiology of gastric cancer. IARC Sci Publ. 1991;22-32. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Cao XY, Jia ZF, Jin MS, Cao DH, Kong F, Suo J, Jiang J. Serum pepsinogen II is a better diagnostic marker in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:7357-7361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Graham DY, Malaty HM, Go MF. Are there susceptible hosts to Helicobacter pylori infection? Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1994;205:6-10. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Dorji D, Dendup T, Malaty HM, Wangchuk K, Yangzom D, Richter JM. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in Bhutan: the role of environment and Geographic location. Helicobacter. 2014;19:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vilaichone RK, Mahachai V, Shiota S, Uchida T, Ratanachu-ek T, Tshering L, Tung NL, Fujioka T, Moriyama M, Yamaoka Y. Extremely high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Bhutan. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2806-2810. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Malaty HM, Kim JG, Kim SD, Graham DY. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korean children: inverse relation to socioeconomic status despite a uniformly high prevalence in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mitchell HM, Li YY, Hu PJ, Liu Q, Chen M, Du GG, Wang ZJ, Lee A, Hazell SL. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in southern China: identification of early childhood as the critical period for acquisition. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:149-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shiota S, Mahachai V, Vilaichone RK, Ratanachu-ek T, Tshering L, Uchida T, Matsunari O, Yamaoka Y. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric mucosal atrophy in Bhutan, a country with a high prevalence of gastric cancer. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:1571-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aragonés N, Pérez-Gómez B, Pollán M, Ramis R, Vidal E, Lope V, García-Pérez J, Boldo E, López-Abente G. The striking geographical pattern of gastric cancer mortality in Spain: environmental hypotheses revisited. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mezzanotte G, Cislaghi C, Decarli A, La Vecchia C. Cancer mortality in broad Italian geographical areas, 1975-1977. Tumori. 1986;72:145-152. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Wong BC, Ching CK, Lam SK, Li ZL, Chen BW, Li YN, Liu HJ, Liu JB, Wang BE, Yuan SZ. Differential north to south gastric cancer-duodenal ulcer gradient in China. China Ulcer Study Group. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1050-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Arnold M, Razum O, Coebergh JW. Cancer risk diversity in non-western migrants to Europe: An overview of the literature. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2647-2659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ronellenfitsch U, Kyobutungi C, Ott JJ, Paltiel A, Razum O, Schwarzbach M, Winkler V, Becher H. Stomach cancer mortality in two large cohorts of migrants from the Former Soviet Union to Israel and Germany: are there implications for prevention? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:409-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nguyen EV. Cancer in Asian American males: epidemiology, causes, prevention, and early detection. Asian Am Pac Isl J Health. 2003;10:86-99. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Maskarinec G, Noh JJ. The effect of migration on cancer incidence among Japanese in Hawaii. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:431-439. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Misra V, Misra SP, Dwivedi M, Singh PA. Point prevalence of peptic ulcer and gastric histology in healthy Indians with Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1487-1491. [PubMed] |

| 22. | El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KE, Bream JH, Young HA, Herrera J, Lissowska J, Yuan CC, Rothman N. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature. 2000;404:398-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1690] [Cited by in RCA: 1624] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Peterson WL, Graham DY, Marshall B, Blaser MJ, Genta RM, Klein PD, Stratton CW, Drnec J, Prokocimer P, Siepman N. Clarithromycin as monotherapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a randomized, double-blind trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1860-1864. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Graham DY, Lew GM, Malaty HM, Evans DG, Evans DJ, Klein PD, Alpert LC, Genta RM. Factors influencing the eradication of Helicobacter pylori with triple therapy. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:493-496. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Pounder RE, Williams MP. The treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11 Suppl 1:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Carlson SJ, Yokoo H, Vanagunas A. Progression of gastritis to monoclonal B-cell lymphoma with resolution and recurrence following eradication of Helicobacter pylori. JAMA. 1996;275:937-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Moayyedi P, Dixon MF. Significance of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer: implications for screening. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7:47-64. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Tanahashi T, Tatsumi Y, Sawai N, Yamaoka Y, Nakajima M, Kodama T, Kashima K. Regression of atypical lymphoid hyperplasia after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:543-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Peterson WL, Fendrick AM, Cave DR, Peura DA, Garabedian-Ruffalo SM, Laine L. Helicobacter pylori-related disease: guidelines for testing and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1285-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lam SK, Talley NJ. Report of the 1997 Asia Pacific Consensus Conference on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, Hunt R, Rokkas T, Vakil N, Kuipers EJ. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1348] [Cited by in RCA: 1336] [Article Influence: 74.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Fock KM, Talley N, Moayyedi P, Hunt R, Azuma T, Sugano K, Xiao SD, Lam SK, Goh KL, Chiba T. Asia-Pacific consensus guidelines on gastric cancer prevention. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:351-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Leung WK, Lin SR, Ching JY, To KF, Ng EK, Chan FK, Lau JY, Sung JJ. Factors predicting progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia: results of a randomised trial on Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gut. 2004;53:1244-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rokkas T, Pistiolas D, Sechopoulos P, Robotis I, Margantinis G. The long-term impact of Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastric histology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2007;12 Suppl 2:32-38. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Wang J, Xu L, Shi R, Huang X, Li SW, Huang Z, Zhang G. Gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia before and after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a meta-analysis. Digestion. 2011;83:253-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Uemura N, Mukai T, Okamoto S, Yamaguchi S, Mashiba H, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Haruma K, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:639-642. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Lee YC, Chen TH, Chiu HM, Shun CT, Chiang H, Liu TY, Wu MS, Lin JT. The benefit of mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: a community-based study of gastric cancer prevention. Gut. 2013;62:676-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |